One of the tricks in this trade is not to be right too soon. With America Alone, for example, what was supposedly "alarmist" when the book came out was New York Times conventional wisdom within a half-decade.

So I was interested to read this piece in The Wall Street Journal:

Has the wave of innovation that transformed the world over the past century fizzled out..? [Jan Vijg] was inspired by an airplane trip in 2006—when he noticed that the plane to Amsterdam wasn't much different from the one that brought him to the U.S. for the first time in 1984. "I just asked myself, how is this possible?" he says.

Actually, it's entirely possible it was the very same plane. In After America, I write on page 27:

Commercial flight hasn't advanced since the introduction of the 707 in the 1950s. Air travel went from Wilbur and Orville to bi-planes to flying boats to jetliners in its first half-century, and then for the next half-century it just sat there, like a commuter twin-prop parked at Gate 27B at LaGuardia waiting for the mysteriously absent gate agent to turn up and unlock the jetway...

And, by the time you factor in getting to the airport to do the shoeless shuffle and the enhanced patdown, flying to London takes longer than it did in 1960.

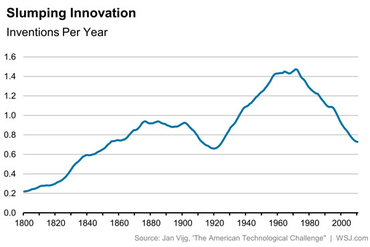

As you can see from the accompanying graphic, the Journal is pretty clear about when the Age of Invention ended:

In his book, Mr. Vijg compiled a list of more than 300 "macro-inventions" that were made between 500 BC and 2010... Mr. Vijg found inventions accumulated rapidly in the last century. But tellingly, the uptrend stopped and turned downward around 1970 and hasn't recovered yet.

In After America, I was a bit more specific than "around 1970" and pinned it in the previous year. Page 28:

Take 1969, quite a year in the aerospace biz: In one twelve month period, we saw the test flight of the Boeing 747, the maiden voyage of the Concorde, the RAF's deployment of the Harrier "jump jet" …and Neil Armstrong's "giant leap for mankind".

And I quote Professor Bruce Charlton:

I suspect that human capability reached its peak or plateau around 1965-75 – at the time of the Apollo moon landings – and has been declining ever since.

It's not all about manned flight. I consider everything from diseases to kitchen appliances:

The first half of the 20th century overhauled the pattern of our lives: The light bulb abolished night; the internal combustion engine tamed distance. They fundamentally reconceived the rhythms of life. That's why our young man propelled from 1890 to 1950 would be flummoxed at every turn. A young fellow catapulted from 1950 to today would, on the surface, feel instantly at home – and then notice a few cool electronic toys. And, after that, he might wonder about the defining down of "accomplishment": Wow, you've invented a more compact and portable delivery system for Justin Bieber!

Today we invent toys. Indeed, we invent toys that are (by no means only theoretically) instruments of state control: Thanks to GPS and the "smart phone" every citizen is now walking around with an NSA electronic ankle bracelet. So, unlike 19th and early 20th century inventions, the newfangled contraptions are not opening up the horizon but binding us tighter to state power.

Yet we don't think of it like that. A few weeks before After America came out, I attended a graduation ceremony in Vermont, for which a bigshot speaker from Wall Street had been flown up from New York. "Your world is changing so fast!" he told them, as is traditional on these occasions.

I couldn't see it myself. For one thing, no matter how fast our world changes, college education seems to get slower and slower, judging from the remarkably aged appearance of many of these Green Mountain "youth". But in a broader sense, precisely what is changing so fast? Their first car is no different from my first car. Which was no different from my grandfather's first car. To be sure, they've dispensed with the hand crank and rumble seat and installed a cup-holder and iPod dock, but essentially it runs on the same technology as a century back. Which are the faster-moving times? The age that invents the internal-combustion engine? Or the age that plugs a Pharrell Williams download into it?

Since the publication of After America, I find that that's the part that most annoys those folks otherwise supportive of my thesis. After all, they point out from various corners of the planet, without the Internet they'd never have heard of me. Fair enough — if your measure of societal progress is more efficient means of Steyn distribution. But I can't help feeling there ought to be more to it than that. So I'm glad to see The Wall Street Journal addressing the topic. If nothing else, it might stop their more eminent readers from trotting out that fast-changing-world guff up and down the land every commencement season.

~By the way, Ed Driscoll has a splendid piece on the no longer oxymoronic concept of "rock Muzak" and some of its unforeseen consequences. I am, as you'd expect, a purist in matters of supermarket music: light orchestral versions of "I Left My Heart In San Francisco" and the theme from A Summer Place, and strictly no vocals. But I would add one postscript to what Ed wrote, with reference to the topic above: That if you define the peak of human accomplishment as the ability to hear Ke or Kanye wherever you go 24 hours a day, then to be without them is by definition a diminished and backward experience. So a convenience store supplies this stuff as an accompaniment to buying a Pop Tart or pumping gas because this - and nothing else - is what it means to be modern. To quote the line Ed quotes me quoting from Allan Bloom:

It may well be that a society's greatest madness seems normal to itself.

Oh, and pumping gas takes longer than it did 50 years ago.

~After America was a difficult book to write, but it holds up pretty well, I regret to say - not least with regard to the vanishing of American power. If you'd like to give it a go, personally autographed copies are exclusively available from the SteynOnline bookstore, and sales go to support my end of the upcoming Mann vs Steyn epic showdown in DC Superior Court. Speaking of which, in today's Financial Post Ross McKitrick analyzes the current global-warming "hiatus", as the IPCC et al are now calling it. Professor McKitrick says that, given the failure of their climate models, it should be more precisely labeled a "discrepancy", which is very understated of him. As he points out, the "discrepancy" between the models and the actual temperature record is the longest that has ever existed, and it's still widening. Which suggests that either the "science" of modeling is extremely bad, or it's been corrupted by non-scientific considerations. Either way, it's telling how sober and calm McKitrick's column is compared to the #KochScaifeDenialistPotemkinVillage hysterics of Mann. Not hard to see who has the temperament of a real man of science here.