Given the ongoing furor over President Trump's executive order commanding the State Department cartographer to mark the map of the world with "Here be sh***holes", I thought for our Saturday movie date we should have a film about just how bad it can get. Twenty-four years ago, the Rwandan genocide was just about to get under way: In a hundred days, a million people were murdered - with machetes, all very low-tech. Since then, as I noted only the other day, the machete has been introduced to such boring white-bread places as Shelburne, Vermont, and Dundalk, Ireland, and Gothenburg, Sweden, and Kandel, Germany. But back then you had to go to what the President calls the s***hole countries to be on the receiving end of such vibrant diversity.

How compassionate was pre-Trump America to Sh*tholia? There being no hashtags in those days, President Clinton, the Pain-Feeler-in-Chief, had to slough off the victims with a brusque soundbite nixing international intervention: "The UN has to learn how to say no," he declared. And so 20 per cent of the population of Rwanda was slaughtered, a number so huge that the world chose to hold it at a big, woozy, blurry distance. To mark the tenth anniversary, the editors of the Economist asked, 'How many people can name any of the perpetrators?' I'd say it's more basic than that. How many could tell you whether it was the Hutu killing the Tutsi or the Tutsi killing the Hutu? C'mon, take a guess, without looking it up.

Well, it was the Hutu energetically hacking the Tutsi into oblivion, while the rest of the globe sat back and watched that decade's "never again" genocide as it would the next one (Darfur): Toot, toot, Tutsis, goodbye! In 2004, when Hotel Rwanda was released, I didn't think you could carry off a movie "about" this subject. It's really an anti-story — it's about the cavalry not showing up. And how do you find any human interest in it? These fellows killed a million of their neighbors, in the lowest-tech way possible — with knives — and taking especial care over the murder of the children, in order to wipe out the next generation of Tutsi. They'd slash open three kindergartners and then move on to the house next door. It's a story of lack of human interest.

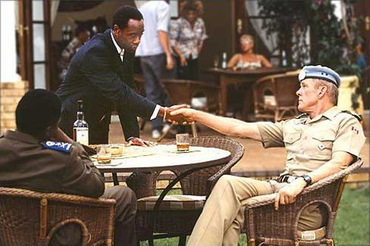

But, remarkably, the director Terry George and his co-writer Keir Pearson almost pull it off, rooting the big picture of anonymous murder in one small precise close-up: the more or less true story of a dapper hotel manager at the four-star Milles Collines in Kigali. Paul Rusesabagina is a Hutu married to a Tutsi, which sounds at first like one of those Hollywood contrivances, but in fact is real - unfortunately real, as it proved for Mr Rusesabagina. In 1994, Paul was an heroic figure in a story with few others, so you can see why, if you're going to do Rwanda: The Movie, this is the tale to tell. The Hôtel des Mille Collines was at that time owned by Sabena, the Belgian airline. It caters to important local bigshots (government ministers, generals) and visiting grandees (UN officials, western media correspondents). Paul knows them all by name, and knows the little extras they like, too — their favorite Scotch and Cuban cigars. He is, naturally, post-tribal, a man who moves ingratiatingly through the highest circles. Don Cheadle, whom I'd hitherto associated with the Sammy Davis gig in the Ocean's Eleven remakes and as Sam lui-même in an agreeably awful Rat Pack karaoke biopic, gives a marvelous performance as a man who defines himself by his sense of style, which in this case is the somewhat generic sophistication of international hotels. As Cheadle glides with faintly oleaginous attentiveness among the tables on the hotel terrace, you see him, without thinking, adjusting his tie, his cuffs, his jacket. These are important things, part of his self-definition.

Like his fellow host at another African establishment, Humphrey Bogart, Paul declines to involve himself with politics. In Paul's case, unlike Rick's in Casablanca, it's not because he's cynical, but because he's naïve enough to assume that enough Rwandans — or enough important, influential Rwandans — feel as he does. They don't. In writing of Sierra Leone and other African nightmares, Robert D Kaplan coined the phrase "re-primitivised man", a concept I mentioned in both America Alone and After America. Here, Terry George brings it to life in one minor character with only two scenes: he's Paul's supplier — for European lager and Glenfiddich, and so on — and in the film's opening he seems a bit of a spiv, a rogue, and a smuggler of weaponry, but still a familiar type one might meet in that line of work anywhere in the world, not least in Bogey's Casablanca. When we meet the guy again, he's visibly re-primitivised, an animal returning from the hunt, his blood lust sated ...but only for the moment. He despises Paul precisely because the hotel manager is "civilized". And so, in an attempt to shatter what he supposes to be a mere veneer of that civilization, he sends Paul back to the Milles Collines via a short-cut, a literal road to hell but paved with something other than good intentions.

The hotel manager's priority is to save his wife Tatiana (Sophie Okonedo), their children, and some 1,268 Tutsi and Hutu who wind up taking refuge in his hostelry. The UN swings by in the unlikely shape of Nick Nolte, playing Colonel Oliver, a figure loosely based on the Canadian commanding officer, General Roméo Dallaire. The real General Dallaire and a band of Canadian-Pakistani-Bangladeshi-Ghanaian-Tunisian peacekeepers had been sent by the UN to Rwanda in 1993 to help implement something called the "Arusha Accords". Suddenly, he finds himself in the middle of a seven-figure bloodbath with not a lot of peace to keep. Dallaire barely recovered from what he saw in Rwanda: a quarter-century on, he still can't go into food stores because he can't stand the smell of meat; and six years afterwards - in 2000 - he was still so distraught he attempted suicide. How close Nick Nolte is to him I can't say: he's not a Francophone for a start, though he does gamely say 'leftenant' in the Britannic fashion rather than 'lootenant' in the American. But Nolte's tics — the lurching about, as if he's come literally rather than merely psychologically unmoored — make the character even more annoying. It's hard to watch him without having total contempt for the UN and their feeble blue helmets in a hue that seems expressly chosen to communicate that they're not real soldiers.

As Nolte explains, the UN were there as peacekeepers, not peacemakers, and so they're forbidden to fire a shot — which, regardless of its merits in a real-life UN mission, seems utterly ridiculous in a movie context involving Nick Nolte. That's to say, the only point to casting a grizzled tic-infested Hollywood bruiser instead of some decent old Quebec rep actor is if he's gonna snarl, "Screw this memo from Boutros Boutros-Asswipe", and open up a can of good ol' all-American whuppass on these guys. But, even without Nolte chewing what's left of the Rwandan furniture, in any telling of this tale you would long for a scene in which the UN guy decides that the situation on the ground has changed and he's going to do what's right. Instead, a ragtag army from a basket-case dictatorship and a mob of machete-wielding morons correctly recognise that the international community's "forces" are a joke and you can humiliate them at will. A little bit of spine would have gone a long way. Had the UN roused itself to jam the Hutu radio station, for example, hundreds of thousands of lives could have been saved. As the film shows us, the president of Sabena back in Brussels got more done to protect Paul and his refugees with one phone call to Paris than the UN did with its pretend general and his incoherent coalition of play soldiers. This is no personal reflection on General Dallaire, but simply a forlorn assessment of what happened: The UNAMIR mission became the embodiment of civilization's passivity, and that's not a role in which to cast Nick Nolte.

Yet, even as outside the gates the entire nation is returning to the Dark Ages, Paul understands that his only weapon is a kind of intimidation by eiquette. Notwithstanding that the Europeans have fled and the rooms are full of desperate refugees, he persists in maintaining the place as a four-star hotel the thugs aren't quite confident enough to overrun. He reminded me, oddly enough, of the famous scene in Carry On Up The Khyber, when the Afghan rebel the Khazi of Khalabar (Kenneth Williams) becomes increasingly enraged when the British refuse to let his attack on the Governor's residence disrupt their afternoon tea. But, in Hotel Rwanda, it seems to work. We see Paul in harrowing scenes on the floor of his bathroom, sobbing, cracking up, but in the end fumbling to get his tie round his collar, brushing down his jacket, and going on with the show, bribing, wheedling, playing for time. He's a calm, unflashy hero in a story otherwise lacking them — at the UN, in the chancelleries of Europe and North America, on the streets of Kigali.

Today, the real-life Paul Rusesabagina lives in Brussels, and back home has a more complicated reputation than the movie would suggest. Ibuka, the coalition of survivors' groups, sneers that he "hijacked heroism" and is "trading on the genocide", and others say, more prosaically, that he charged those who took refuge in his hotel for food and drink. In Rwanda, they no longer speak French, and indeed, somewhat bewilderingly for us old-school imperialists, have joined the Commonwealth, so disgusted were they by the Quai d'Orsay's part in what happened. As for Don Cheadle, he signed on with George Clooney in taking up the cause of Darfur (in another s***hole country, Sudan) , and wrote a book about it called Not On Our Watch, in which capacity he was a guest of mine when I was sitting in for Sean Hannity on Fox News a few years back. A fine actor and a friendly fellow. But his "activism" on Darfur was in the end as passive as that UN mission's was in Rwanda. So Darfur's corpse stacked up unimpeded, as Rwanda's did and as the next one will. But, any day now, we're about due Hotel Darfur.

~If you disagree with Mark's movie columns and you're a member of The Mark Steyn Club, then feel free to take a metaphorical machete to him in the comments. Do please be respectful to fellow commenters, and stay on topic. Club membership isn't for everybody, but it helps keep all our content out there for everybody, in print, audio, video, on everything from civilizational collapse to our Saturday movie dates.

We have more entertainment for you later this evening, with the conclusion of Mark's serialization of Jack London's classic piece of frosty fiction, To Build a Fire. We hope you'll tune in.

What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, aside from being an Audio Book of the Month Club, it's also a discussion group of lively people around the world on the great questions of our time: our latest Clubland Q&A live around the planet aired last Tuesday. It's a video poetry and live music club. We don't (yet) have a clubhouse, but we do have a newsletter and other benefits. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of all that and more, we do have a special Gift Membership that includes your choice of a personally autographed book or CD set from Mark. More details here.