Great Train Robber Ronnie Biggs died on Wednesday, his celebrity much diminished by his final decade. A relatively minor member of the gang that held up the Glasgow-London mail train in 1963, he was captured, convicted, and jailed. And then he bust out, escaped overseas and spent 36 years cocking a snook at the British authorities - until ill health forced him into returning to the UK for, all of things, the prison version of the NHS. Since Biggs' death was announced, several readers have asked for a reprise of this essay - the other side of the Great Train Robbery, as seen by Detective Chief Superintendent Jack Slipper, Javert to Biggs' Valjean for some four decades until his death in 2005. This obituary of Slipper of the Yard is from the book Mark Steyn's Passing Parade:

"He was always affable and very much a gentle giant," said Bruce Reynolds. "He was one of the old school," agreed one of Reynolds's colleagues.

Gentlemen publishers? Art dealers? Well, Reynolds has a small antiques business in South London these days, but he was being quoted in his capacity as the mastermind of Britain's Great Train Robbery. His colleague is a rather less eminent member of the United Kingdom's criminal class. And the man they were eulogizing was Slipper of the Yard—Detective Chief Superintendent Jack Slipper, the last British police detective to become a household name. If "Slipper of the Yard" sounds vaguely like a 1950s British movie—black-and-white crime thriller, decent old stick of a copper, girlfriend one of those burly English birds radiating health rather than sex, you catch it late at night in some motel and stick around waiting for the gunfire to start but it never does, except for a single shot in the final reel when the sweaty, rodentlike villain panics—well, Jack Slipper certainly looked the part of the Scotland Yard man. Ex-RAF, he was a tall man with copper-sized boots (size 12 in Britain, 13 in America) and a bristly pencil moustache. The 'tache was standard issue for police detectives when he started, though his was a rare survivor by the time he retired, in 1979.

If Slipper was indeed an old-school copper, Reynolds and Co. were old-school robbers, remnants of not exactly an age of innocence but a time many Britons now look back on fondly: the cops didn't carry guns, and neither did the robbers; the former were known as the "Old Bill," the latter were "diamond geezers"; and when the Bill collared one of the ne'er-do-wells, he'd say, "You're nicked, chummy," and the geezer would respond, "It's a fair cop, guv." The moral contradictions of this era of British crime are summed up in misty Cockney reminiscences of the psychopathic Kray twins: lovely boys, proper gentlemen, always treated everyone with perfect manners—well, except for the people they killed. Years ago I used to date a nurse at the Royal London Hospital, and after her shift we'd go for a drink round the corner at the Blind Beggar, an East End landmark famed for one night in the sixties when Ronnie Kray strolled into the pub and shot his gangland rival George Cornell between the eyes. The jukebox was playing the Walker Brothers' No. 1 hit "The Sun Ain't Gonna Shine Anymore." "The sun ain't gonna shine for him anymore," said Ronnie.

Nor, in the end, for British gangland's reputation as a playground for lovable rogues. Today London has worse property crime than New York, the diamond geezers have been succeeded by Jamaican drug gangs—"Yardies" with Uzis—and if you take the East London Line to Whitechapel for a pint at the Blind Beggar, remember that since the July 7 bombings the metropolitan police have had a shoot-to-kill policy on the tube. But somewhere in its folk memory much of Britain still holds a soft spot for the lads responsible for the events of August 8, 1963. That's when Bruce Reynolds and his comrades pulled off the Great Train Robbery, seizing the Royal Mail express from Scotland to London as it passed through Buckinghamshire and getting away with £2.6 million in used notes, which was quite a sum in 1963 and today translates to more than $65 million.

They'd cleaned out the train without firing a single gunshot, but the driver, Jack Mills, was uncooperative, and one of the gang brutally whacked him with a cosh. Nevertheless, at a time of imperial decline abroad and government scandal at home, the public seemed to take a perverse patriotic pleasure in the crime. Pace Dean Acheson, Britain may have lost an empire but it had found its rolling stock—stripped clean with immense boldness and panache. "Britons may not admit they are proud," wrote The Daily Telegraph of Sydney, "but in private many are thinking 'For they are jolly good felons.'"

If only they'd planned the post-robbery phase as efficiently. Investigation of the Great Train Robbery fell to the Sweeney—the metropolitan police's mobile armed-robbery division, the Flying Squad ("Sweeney" is Cockney rhyming slang: Sweeney Todd = Flying Squad). Among the six detectives assigned to the case was a junior sergeant named Jack Slipper, who got his first break when a woman named Charmaine Biggs went on a shopping spree in a fancy West End store and paid in cash. Her husband was a petty criminal named Ronnie Biggs, and when he returned home on September 4, Detective Sergeant Slipper was waiting for him. The Great Train Robbery had been cracked within a month. The following April, Biggs and the others were sentenced to thirty years in prison.

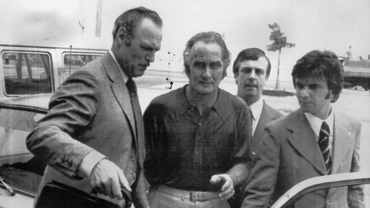

He didn't stay long. After fifteen months Biggs escaped from Wandsworth Gaol, getting over the wall with a rope ladder and then dropping into a waiting furniture van with a hole in its roof. He skipped to France and then Spain, Australia, and finally Brazil, where in 1974 he renewed his acquaintance with Slipper of the Yard. Tipped off by a Daily Express reporter that Biggs was holed up in Rio, the detective flew out on a secret mission to recapture his man. The fugitive opened his hotel-room door to be confronted by a most un-Brazilian-looking cove with a familiar pencil moustache. "Long time no see, Ronnie," said Slipper—a line he'd apparently rehearsed.

"Fuck me," said Ronnie—a more spontaneous reaction.

That's a vernacular expression indicating amazement, not an invitation—and in any case the position was already taken, by a samba dancer called Raimunda, as Slipper was shortly to discover. The copper and his junior colleague, Sergeant Peter Jones, cuffed their man and took him to the Copacabana police station. Big mistake. Slipper had neglected to look into whether Britain and Brazil had an extradition treaty (they didn't), and by the time the authorities came to make their decision, Raimunda had revealed that she was carrying Ronnie's child. As the soon-to-be father of an impending Brazilian citizen, Biggs could not be deported. With the spectacular front-page undercover swoop reduced to an interminable extradition case, the coppers took a plane back to Heathrow. In the middle of the flight, when Sergeant Jones got up to head for the washroom, a Daily Mail photographer pounced. The picture appeared in the following day's paper: Slipper dozing next to "The Empty Seat," as the headline put it. Slipper of the Yard was now Slip-up of the Yard, a bungler who had let Britain's most wanted man slip through his fingers. Biggs's Javert was transformed overnight into Inspector Clouseau.

They made a BBC drama about the incident a few years later, and Slipper successfully sued over his portrayal as a bumbling flatfoot. He complained about material such as the scene in a Rio bar where he orders "uno beero and another uno beero" and then turns to his sergeant and mutters, "You see what we're up against, Peter. They only talk Brazilian down here." The screenwriter Keith Waterhouse recalls him as a minefield of malapropisms who told him, "No one minds a bit of dramatic licentiousness, Keith, but you have made me out to be a right prat."

By then Slipper of the Yard was the Tom Hanks figure in Catch Me If You Can—an earnest plodder in a raincoat. And Biggs, though no Leonardo DiCaprio, was the larky chancer who'd got away with it and escaped dreary old England for a life of "dramatic licentiousness" in Latin America—nonstop booze 'n' birds and an endless parade of fawning tourists and minor celebrities. He had a cameo in the Sex Pistols movie The Great Rock 'n' Roll Swindle, and made a record with the German rock band Die Toten Hosen.

In fact Jack Slipper was a brilliant policeman, and had been ever since he was a young officer on traffic duty outside the Royal Albert Hall and leaped on his bike to take down a thug who'd slashed a guardsman's throat. He may have dressed "old school," but he was a very modern policeman. He destroyed the London underworld's "honor among thieves" by assembling a network of "supergrasses"—highly placed gangland informers. And he cracked one important case after another, from a triple slaying of unarmed Shepherd's Bush policemen in 1966 to a £12 million Bank of America robbery.

Nevertheless, he accepted that fate had yoked him to the man who got away, and that he'd forever be the straight man in the Biggs 'n' Slipper double act. Happy to fly out to Japan in 1985 for a Nippon Television special, he chitchatted amiably with his nemesis on a satellite linkup to Brazil. "How are you getting on?" asked Slipper, sounding to The Guardian's Tokyo correspondent like a genial headmaster running into an old pupil.

"I'm getting on very well indeed," said Biggs. A few years later a retired Slipper went to Rio to see for himself. "His villa was bog-standard and in the wrong end of town. His swimming pool was so black with algae even a stickleback couldn't live in it. He was flogging T-shirts to tourists to make a living."

Ronnie's Brazilian son had been a child pop star, Little Biggs, for a couple of years, but that was over. And in the end sun-drenched days and bossa nova beach babes in minimal thongs are small consolation if you're pining for a warm pint and a Marmite sandwich. Over a beer Slipper asked, "So, Ronnie, does crime pay?" Biggs shook his head. "I've left my family and my home. I've got nothing left." In 2001, broke and sick, he returned to Britain after 13,068 days on the run to serve his remaining twenty-eight years—because the prison hospital was the only way he could get access to medical treatment. The Great Train Robber had finally hit the buffers.

Golfing away in retirement, the dogged copper said he wouldn't join the police now—it was "too political." Today's famous British bobbies are self-flagellating administrators, such as a former subordinate of Slipper's turned metropolitan police commissioner, Sir Ian Blair, and his deputy, Brian Paddick, London's "senior gay policeman." For Blair and Paddick, policing seems to involve mainly berating themselves for their force's "systemic racism" and "homophobia." Out in the shires chief constables responded to the July 7 bombings by issuing mandatory green ribbons to their officers so they could show solidarity with British Muslims worried about "Islamophobia." Jack Slipper was "old school" enough to think that the best form of community outreach was to lower the crime rate. And there's not been much of that in the British police recently: long time no see, as he would have said. Slipper of the Yard will be the last detective so styled. To today's Scotland Yard it sounds vaguely parodic. Which, of course, is a big part of the problem.

~This essay is adapted from Mark's book Mark Steyn's Passing Parade, available from the SteynOnline bookstore