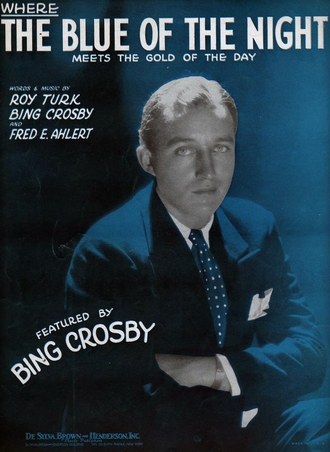

For almost half a century, this was as well known as any song in America. The man who sang it was the biggest-selling recording artist of all time, and this was the biggest-selling recording artist's theme tune, the one the band struck up at the start of every radio, TV or stage show:

Where The Blue Of The Night

Meets the gold of the day

Someone waits for me...

Forty years ago - October 14th 1977 - a golden half-century met the blue of the night on a golf course in Madrid: After finishing 18 holes at La Moraleja with three Spanish golf champions, Bing Crosby had a massive heart attack, collapsed, and died. He'd headed to his Iberian retreat for a few days of rest and relaxation after some sell-out concerts at the London Palladium, a recording session for BBC radio, a pre-taping of his annual Christmas show, and some tracks for a new album: a typical few days for an "Old Groaner" who was old but assumed he still had plenty of groaning ahead.

At the time of his death, he had, as noted, sold more records than anyone else; "White Christmas" was the biggest-selling single of all time, with "Silent Night" not far behind, and indeed the very concept of Yuletide hit records was among the many debts show business owed to Crosby. For decades, he was one of the biggest box-office stars in Hollywood, which isn't bad for a fellow for whom the designation "actor" came well after "singer" (and even "businessman"). And, even though acting wasn't really what he did, he did it very well. Watch Bing in almost any nothing scene in any movie - fixing Rosie Clooney a sandwich in White Christmas, say: he's always very real, one of the great naturally naturalistic actors of all time. And, if he wasn't doing much acting by the mid-Seventies, the final albums were still pretty good: the baritone was as warm as ever, the phrasing was confident, and songs like "Time On My Hands" and "Yesterday When I Was Young" reveal a Crosby capable of infusing a lyric with real depth. He introduced more hit songs than any other singer and, while a lot of them were passing fancies, a substantial percentage went on to be enduring standards: "Pennies From Heaven", "Moonlight Becomes You", "Swinging On A Star", the last of which Burke & Van Heusen were inspired to write after hearing Bing at a party tell his son to stop being such a mule:

And by the way if you hate to go to school

You may grow up to be a mule.

Where did it all go? Within a decade of his death, you could wander into a record store and find the biggest-selling record artist had dwindled down to a couple of compilation CDs on weird European labels you'd never heard of. To most Americans under a certain age, the name is meaningless except for one song heard for one month every year, underpinning every lite-rock, country, oldies or whatever station that switches in December to a seasonal sleighlist of "Holiday Favorites", than which no favorite is more favored than "White Christmas". That's what a half-century golden day shriveled down to in the blue of the night: Bing Crosby? The guy who sings "White Christmas"? Does he do anything else?

When a star that bright dims so quickly, it's usually because the keepers of the flame aren't any good at keeping it. A decade or two after the death of a singer or composer or novelist, any diminution in reputation is as much to do with the inept stewardship of his estate by the next of kin and their various advisors as it does to any judgment by posterity. What Nancy, Frank Jr and Tina have done with the Sinatra catalogue, for example, is in marked contrast to the withering of Bing's legacy. It's not necessary to retell the grim story of Crosby's first family, and his second bunch of kids were barely out of short pants at the time of his death. But his eclipse is sad and unnecessary.

So on this anniversary let's go back before the pipe and cardigan and golf gags and Christmas show banter, to the young Bing of the late Twenties and early Thirties. Artie Shaw described him as "the first hip white person born in the United States". "Ever since Bing first opened his mouth," said Louis Armstrong, "he was the Boss of All Singers" - which is one reason "Mr Satch and Mr Cros" (to quote "Gone Fishin'") made so many records together. And the first time William S Paley of CBS heard Bing open that mouth, it changed the course of his fledgling radio network. Paley was on the transatlantic liner the SS Europa, on his third day at sea, strolling along the deck, when he heard a phonograph record coming from a nearby stateroom - something about somebody surrendering, dear - and he was transfixed. He tracked down the source of the sound and persuaded the stateroom's occupant to let him look at the label on the disc: "I Surrender, Dear. Vocal refrain by Bing Crosby." Then he went straight to the ship's telegraph office and sent a cable to New York: "SIGN UP SINGER NAMED BING CROSBY STOP".

What Paley heard, like everyone else, was the throb in the voice. When Bing started in the Twenties, there were theatre singers - guys like Jolson, aiming at the back of the balcony: they made records but the records were, in essence, a souvenir of a theatrical performance. Then they invented real microphones, and immediately a new generation of mannered over-compensaters showed up, like Whispering Jack Smith and other fellows who, in Will Friedwald's phrase, "overdid the understatement". Crosby was the first truly natural singer of the electronic era - the man who, as Friedwald puts it, "came up with the kind of 'natural' that worked: the warm B-flat baritone with a little hair on it".

Before he was a solo, he was one-third of a trio, and before the trio he was one-half of a double-act. Paul Whiteman hired Bing and Al Rinker as a vocal duo in 1926. They were terrible, and the theatre manager demanded Whiteman fire them. Instead, the bandleader signed a third singer, Harry Barris, and renamed the act the Rhythm Boys. The Rhythm Boys liked to raise a little wilder rhythm out of hours, and, though Whiteman tolerated the booze and the girls and the parties, when Bing got tossed in jail he decided to fire all three of them. The Rhythm Boys were picked up by Gus Arnheim, who quickly figured out that the guy the audience wanted to hear was Bing. Bad news for Al and Harry, but in the latter's case he was also a composer, and one day, hearing Crosby singing variations on Sigmund Romberg's "Lover, Come Back To Me", he was inspired to compose the first ballad purpose-written for Bing:

We've played the game of "stay away"

But it costs more than I can pay

Without you I can't make my way

I Surrender, Dear

I may seem proud, I may act gay

That's just a pose, I'm not that way.

'Cause deep down in my heart I say,

I Surrender, Dear...

Aside from the titter-provoking couplet (at least to contemporary ears) about acting gay but not being that way, "I Surrender, Dear" is a ballad of more or less generic ardor. The lyric is by Gordon Clifford ...and Bing Crosby. Bing has his name on a handful of songs from those early years. Was he just cutting himself in on a piece of the royalty action? Star singers did that a lot back then, and still do. (Two friends of mine, a very eminent songwriting team, were invited to write a song for a Céline Dion album a couple of years back, but were informed that she'd want a third of the copyright.) But, in this case at least, it seems likely that Bing actually tossed in a few lyric contributions for his buddy Barris. The Rhythm Boys had a lot of fun with jazzy novelties like "Happy Feet" and (another Barris number) "Mississippi Mud", but "I Surrender, Dear" killed the act stone dead: Audiences wanted to hear, as Crosby biographer Garry Giddins put it, "that astonishing singer with the throb in his voice, not a trio of hepcats".

Harry Barris might reasonably have expected to get at least a couple of songwriting gigs out of the new solo act - or maybe something even more lucrative. After all, for his new CBS radio show, Bing would need, like everybody else, a theme song. Surely "I Surrender, Dear" was the obvious choice. But Crosby wasn't convinced that surrendering to someone was quite the right message for a radio theme, and started casting around for alternatives. It came down to a choice between "Love Came Into My Heart" by Burton Lane (composer of Song of the Week #54 "How About You?") and Harold Adamson (lyricist of Song of the Week #34 "Time On My Hands"), and an alternative ballad by Fred Ahlert and Roy Turk. Fred Ahlert is the guy who wrote "I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Right Myself A Letter", whose immortal line "Kisses on the bottom" provided the title for Paul McCartney's recent album of standards. Roy Turk had had a big hit in 1926 with "Are You Lonesome Tonight?" and (posthumously) an even bigger hit four decades later when Elvis revived it. But in 1927 lyricist Turk teamed up with composer Ahlert and had a great run of songs that are still high earners today - "I'll Get By", "Walkin' My Baby Back Home", "I Don't Know Why (I Love You Like I Do)", and, of course, "Mean To Me (Why must you be mean to me?)" with its ingenious O Henry twist in the tail on the title phrase: "Can't you see what you mean to me?". (I was interested to discover a few years back that Fred Ahlert's grandson Arnold Ahlert is a pundit and commentator, who's never mean to me and indeed quotes me favorably from time to time.)

For the most part, Turk & Ahlert songs are as natural as walking, whether with your baby back home or just down the sidewalk to the corner newsstand. They have something that's very hard to fake: a sense of inevitability about them. In 1931, though, it took them a couple of goes to get it right:

When the gold of the day

Meets the blue of the night...

Well, you can see what they're getting at: The order has a kind of logic to it. But it just doesn't sing as well. So Roy Turk re-jigged it:

When the blue of the night

Meets the gold of the day...

Almost there. Turk made one further change: not "when the blue", but "where", which makes what had sounded previously like an eagerly awaited date into something more mysterious. Ahlert's tune is a simple waltz, but it works in four/four, as a shamrock-hued ballad, or just as a series of pleasing monosyllables to show off the richness of Crosby's baritone:

Where The Blue Of The Night

Meets the gold of the day

Someone waits for me

And the gold of her hair

Crowns the blue of her eyes

Like a halo tenderly

If only I could see her

Oh, how happy I would be...

Aside from singing it on the radio every week for years, he recorded it anew once every decade or so, but that very first disc - from November 1931, with Eddie Lang's marvelously cool guitar - is hard to beat. It's the perfect intro theme: It's anticipatory, particularly once Turk switched round the "gold of the day" and the "blue of the night". For when the blue surrenders to the first golden shaft, it's dawn, a new day, and a world of possibilities.

Yet that original recording has one blemish: a verse. Bing sings:

Why do I live in dreams

Of the days I used to know?

Why can't I find

Real peace of mind

And return to the long ago?

It's one of those verses that explains the song before you hear it, but in doing so makes it more ordinary. Still, you can't blame Bing for recording it. He was, after all, a co-writer of the song.

Okay. So which bit of it did he co-write?

As it happens, the verse.

So, on that first recording, he was in effect justifying his cut of the royalties. By the time he re-recorded it as part of a "musical autobiography" for Decca in the Fifties, he stuck with the chorus and, in a spoken introduction, credited it only to "Turk & Ahlert". "Where The Blue Of The Night" was hard on Harry Barris, his old singing partner and author of "I Surrender, Dear". Barris' daughter Marti said it "broke his heart" when Bing didn't choose "I Surrender", but it was surely the right choice: America was surrendering to Crosby, not the other way round.

Yet being Bing's theme wasn't an unmixed blessing for "Blue Of The Night". Yes, you get sung every week, decade in, decade out: you're earning money - but you're not being heard as a song. You're a cue, a walk-on, an intro. "Thanks For The Memory", a superb song, is under-recorded because it was Bob Hope's personal national anthem for almost 70 years. Likewise, I couldn't recall the last time I'd heard "Where The Blue Of The Night (Meets The Gold Of The Day)" in a non-Bing context until one day in 2007 a copy of John Prine and Mac Wiseman's lovely album Standard Songs For Average People showed up in my mailbox. Prine and Wiseman aren't exactly average - the latter's a bluegrass pioneer, the former a country-folkie once tipped as the new Dylan. And the "standard songs" aren't that standard, either, but an odd mix of Patti Page, Ernest Tubb, Kris Kristofferson and the Baptist hymnal. But their pared-down countryfied "Blue Of The Night" is very affecting. Wiseman is old enough to remember hearing it as a child when his mom tuned in the Crosby show every week, but his version's more than just an affectionate tribute: It reminds you of how pleasing the song is in its own right.

As for the new Bob Dylan, well, the old Bob Dylan liked "Blue Of The Night" enough to borrow its chords and structure for a song called "When The Deal Goes Down", which is no match on the original.

"I really think," said Bing in old age, "I'd trade anything I've ever done if I could have written just one hit song." He tried, occasionally. Almost to the end, he enjoyed writing parodies. And he'd occasionally take an idea to an old pal like Johnny Burke (lyricist of "Pennies From Heaven" and "Swinging On A Star") in hopes of getting some help working it up. But the one enduring "hit song" with Crosby's name on it was "(I Don't Stand) A Ghost Of A Chance (With You)", written in 1932 with Victor Young and Ned Washington. Other than that, Bing Crosby's songwriting reputation rests on some lyrics to the verse of a great Fred Ahlert tune - one-third of a ballad that deserves to be more than just an old radio theme:

Where The Blue Of The Night

Meets the gold of the day

Someone waits for me

- and a fine song waits to be rediscovered.

~If you're a Mark Steyn Club member and disagree with any or all of the above, feel free to let rip (without getting blue in the night) in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges, so get to it! You can also enjoy personally autographed copies of A Song for the Season and many other Steyn books at a special member's price.