Come on an' hear!

Come on an' hear!

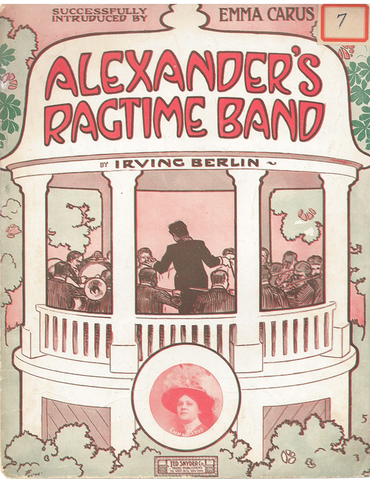

How's that for an opening? A chorus that tells you, in its very first line, listen up, you're about to hear something! What followed was "the alarm clock that awoke American popular music". That's how Alan Jay Lerner, the author of Camelot and My Fair Lady, described it to me many years ago, and you don't have to accept that premise one hundred per cent to recognize that "Alexander's Ragtime Band" was a landmark, a phenomenon, an alarm clock if not for "American popular music" then at least for its most successful practitioner. Irving Berlin is the composer and lyricist of our Song of the Week #22 ("God Bless America"), #37 ("White Christmas"), #59 ("Cheek To Cheek") and #124 ("Easter Parade"). But before any of those great anthemic hits there was "Alexander's Ragtime Band". Copyrighted by the Ted Snyder Company, the publishing house at which Berlin was then employed, on March 18th 1911, this week the song celebrates its one hundredth birthday: Come on an' hear...

Alexander's Ragtime Band

Come on an' hear!

Come on an' hear!

It's the best band in the land

They can play a bugle call like you never heard before

So natural that you want to go to war

That's just the bestest band what am

Honey lamb!

It was not the first song Berlin wrote. That honor goes to a lyric he'd rattled off four years earlier, to a tune by a fellow called Nick Nicholson: "Marie From Sunny Italy". He was still Israel Baline back then, Izzy from not so sunny Siberia, where he'd have grown up in obscurity had not the Cossacks ridden in to raze the village and send his parents scuttling west. He was born in a dot on the map called Temun in 1888. "Irving's seven years older than me," his fellow songwriter Irving Caesar, author of our Song of the Week #23 ("Tea For Two") and #131 ("Just A Gigolo"), told me some years ago. "But we both grew up on the Lower East Side like a lot of songwriters - Kalmar and Ruby, the Gershwins. Our parents arrived from Europe at Ellis Island, and they'd just settle in the ghetto: those were the days before immigrants started moving north or out to Brooklyn. I've never known why so many songwriters came from the East Side, but I will say this. The Jewish immigrants always liked to rhyme. You'd call out to one, 'Izzy!' And he'd say, 'I'm not busy.' And most of us learned from the little Jewish patter songs of those days. Irving started as a singing waiter - he worked at Nigger Mike's in Chinatown."

Nigger Mike? Mike was not, in fact, a Negro, but a swarthy Russian Jew who ran a cafe underneath Chinatown Gertie's whorehouse. Likewise, Chinatown Gertie was not, in fact, a Chinawoman. But in those days, in that part of town, a lot of folks belonged to one "minority", as we would now say, or another. In 1907, at Callahan's round the corner, the piano player Al Piantadosi and Big Jerry the waiter had written an Italian-type tune called "My Mariucci Take A Steamboat", and now everyone was abandoning Nigger Mike's for Callahan's to hear the thing. So Nigger Mike turned to his waiter and piano player and sneered, "How come you guys can't write a song?" So the piano player came up with a tune and Izzy Baline knocked out a lyric: "Marie From Sunny Italy". They took it to Jos. W. Stern & Co. and divided the advance of 75 cents in two (no word on who got the extra penny). As its author liked to recount in subsequent years, nobody bought the song except Joe Schenk, the drug clerk round the corner. Otherwise, the sheet music was notable only for a typographical error on the cover:

Words by I. Berlin

Izzy Baline liked that, and decided to go all the way: He became, as George M Cohan introduced him at the Friars' Club, "a Jew boy that has named himself after an English actor and a German city". The newly minted "Irving Berlin" left Nigger Mike's and put "Marie From Sunny Italy" through every other ethnic wringer: "Oh, How That German Could Love", "Yiddisha Eyes", "Colored Romeo", and of course:

My father was an Indian

My mother was his wife

My uncle almost died

Until a kind judge gave him life

My brother was the president

Of ev'ry Indian club

My sister was a chambermaid

So that made me a Hebrew.

He could have gone on writing interchangeable ethnic novelty numbers for years. Many songwriters did: There were unlimited numbers of comics and vaudevillians who needed material. Instead, one day in 1910, Berlin found himself composing what was intended to be his first instrumental. By this stage, he had graduated from lyricist to lyricist-composer, and taught himself to pick out tunes on the piano by playing only in F sharp, on the black keys (for self-taught pianists, the three and the two stand out more easily). And he noticed that there was a market for ragtime piano instrumentals, and thought he might as well get a piece of it. So he wrote one, played it through a few times, and nobody in the office liked it. So he put a lyric to it, and still no one in the office liked it. So he put it to one side without even noting the tune down on paper, and went on to other things.

And that was that, until months later he was getting ready for a trip to Florida with Jean Schwartz, composer of "Chinatown, My Chinatown", and the Broadway producer Jack M Welch. As Berlin's friend Rennold Wolf wrote, for a piece in the August 1913 Green Book Magazine called "The Boy Who Revived Ragtime":

Just before train time he went to his offices to look over his manuscripts, in order to leave the best of them for publication during his absence. Among his papers he found a memorandum referring to 'Alexander', and after considerable reflection he recalled its strains. Largely for the lack of anything with which to kill time, he sat at the piano and completed the song.

As Berlin told Wolf, "the greater portion of the song was written in ten minutes" - and then it sat around for months waiting to be finished. And even then his friend and publisher, Ted Snyder, didn't care for it. It was too long (32 bars, twice the length of a traditional 16-bar chorus), too rangey (an octave and four), and the verse and chorus were in different keys - which no popular pop song had ever attempted. Nevertheless, Berlin said that was the way he wanted it: He had concluded, entirely correctly, that the chorus was the most memorable part of a song. Therefore, if you made the chorus longer a song would be even more memorable. And thus did Irving Berlin help effect the biggest-single change in pop music in the early 20th century: the demise of the Victorian-style ballad with short 16-bar choruses and multiple story verses, and the rise of the 32-bar popular song with merely an introductory and entirely optional verse.

Still, it's hard to believe Berlin intended this tune to be any kind of trailblazer - and even harder to believe he wrote it as an instrumental. "I find no elements of 'ragtime' in it," pronounced Alec Wilder in his study of American Popular Song. And he's right - if, by ragtime, you mean the rags of Scott Joplin. Instead it's a march with some minimal nods toward syncopation. On the other hand, if it's short of "elements of 'ragtime'", it makes up for it with elements of pretty much everything else, including a bugle call and Stephen Foster's "Way Down Upon The Swanee River". Indeed, aside from the opening bars - "Come on an' hear!" - there are, noted Wilder, no other musical ideas in the song. Which seems odd for what was supposed to be Berlin's first instrumental.

It took the words to tie it all together. The tune turns into a bugle call, and the lyric explains why:

They can play a bugle call like you never heard before

So natural that you want to go to war...

Oh, right. Then it's back to the "come on an' hear" strain:

Come on along

Come on along

Let me take you by the hand

Up to the man

Up to the man

Who's the leader of the band...

At which point we segue into Foster's "Swanee River", and once again the lyric tells us why:

And if you care to hear the 'Swanee River' played in ragtime

Come on an' hear!

Come on an' hear!

Alexander's Ragtime Band!

Why Alexander? Why not Jim or Bud or Gaylord or Nigel? Well, Alexander was an established stereotypical Negro in Tin Pan Alley "coon songs" - "Alexander, Don't You Love Your Baby No More?" The idea was that Alexander was an absurdly pretentious name for a comic figure. Berlin himself had written the previous year a song called "Alexander And His Clarinet". So "Alexander" was a formula convention, and "ragtime", in the Berlin sense, seemed to mean little more than rhythmic pep. But his new song had that in spades, starting from the first bars of the verse. Alec Wilder thinks the great strength of the tune is that it's not "crowded with notes", and he's right. In those first three bars, the song comes in on the second beat:

[Thwack] Oh, ma honey

[Thwack] Oh, ma honey

[Thwack] Better hurry and let's meander

[Thwack] Ain't you goin'?

[Thwack] Ain't you goin'?

[Thwack] To the leader man

[Thwack] Ragged meter man...

Hurry and meander? How do you do that? Well, in a sense, the song lives the paradox: It has an undeniably purposeful rhythmic drive, and yet it has time to meander entirely naturally through bugle calls and Swanee nostalgia. Whether or not it was "ragtime", in 1911 this was new and exciting, and those off-beat bars kicked off the song with an almost irrepresible energy. Emma Carus, the vaudeville star, certainly heard something in it. She swung by the Snyder office ahead of her forthcoming tour to see if they had any new material, and left with a copy of "Alexander". On April 17th 1911, she gave the first public performance of the song at the Big Easter Vaudeville Carnival at the American Music Hall in Chicago - although two nights earlier the comedian Otis Harlan is rumored to have whistled part of the number on stage in Atlantic City. At any rate, Mrs Carus took "Alexander's Ragtime Band" on to Detroit and then to New Brighton, New York. On May 25th, a reviewer from the Sun reported:

It is in her songs that Mrs Carus is most impressive, and she has five new ones that are worthy of the headliner. 'Alexander' has all the swing and metrical precision of 'Kelly', which Mrs Carus brought to this country from England three years ago.

In a few days 'Alexander' will be whistled on the streets and played in the cafes. It is the most meritorious addition to the list of popular songs introduced this season. The vivacious comedienne soon had the audience singing the chorus with her, and those who did not sing whistled.

The New York Sun's man was a wee bit off in his prediction of "a few days". But three nights later "Alexander's Ragtime Band" received its premiere in Manhattan at the Friars' Frolic Of 1911 at the New Amsterdam Theatre. As the title suggests, this was a Friars' Club entertainment, with lots of songwriters on stage - the aforementioned George M Cohan and Jean Schwartz, plus Ernest R Ball, composer of our Song of the Week #92, "When Irish Eyes Are Smiling". And so it fell to the author himself, with a little help from Harry Williams, to present "Alexander" to a New York audience. "I remember him introducing it," Irving Caesar told me:

Irving sang - he had no voice but he was very effective - and there was a spontaneous reaction. We all knew we'd heard something we'd never, ever forget. Today, a song can be heard in millions of places simultaneously, but in those days it could only be sung in one place at one time. Yet, within a few months, it was a hit all over the world.

Casesar was right. Within a few weeks, Billy Murray's record of the song went to Number Two, and Arthur Collins and Byron Harlan's version got to Number One and stayed there through the autumn. The following year - 1912 - the now phenomenally successful songwriter took his first overseas trip, sailed to Britain, disembarked at Southampton, and upon handing over his passport was asked by the customs inspector whether he was the same Irving Berlin as the Irving Berlin who'd written "Alexander's Ragtime Band". He stepped off a train at Victoria Station and heard a newsboy whistling the song. This was before the invention of radio, and with records barely out of wax cylinders, yet Berlin was a bona fide global celebrity. He was now "The Ragtime King" - whatever that meant. Whatever it meant, Dr Ludwig Gruener of Berlin wanted to steer well clear. German Berlin was east and Irving Berlin was west, and ne'er the twain shall meet if Dr Gruener, writing in the fall of 1911, had any say in the matter:

Hysteria is the form of insanity that an abnormal love of ragtime seems to produce... It is as much a mental disease as acute mania - it has the same symptoms. If there is nothing to check this form, it produces idiocy.

According to Dr Gruener, on a recent trip to America, 90 per cent of the inmates of the lunatic asylums he visited were "abnormally fond of ragtime". Berlin's biographer Edward Jablonski suggests the Gruener thesis was undermined by a Philadelphia newspaper report that December:

Ragtime Melody Prevents Panic At Fire In Film Show

As readers know, among the other consequences of my battles over free speech is a complete contempt for lazy brain-dead twerps droning like zombies Oliver Wendell Holmes' fatuous line about shouting fire in crowded theatres. However, if you do happen to be in a crowded theatre when someone shouts "Fire!", a useful tip is to ask the house pianist to play "Alexander's Ragtime Band". In this particular Philly movie joint, the cry of "Fire!" had caused the patrons to stampede in panic - until the fellow tickling the ivories launched into Berlin's big hit. The mad panic ceased, and the moviegoers departed in an orderly fashion: As the newspaper reported, "All the boys whistled and the women hummed." And, despite Dr Gruener's best efforts, within a year, lederhosen-clad lads in Berlin were whistling, too, and dirndled fraulein humming. And so were the Spanish, French, Italians and Russians.

Rennold Wolf's title for the Green Book Magazine article got it right: Berlin "revived" ragtime - if not the music, then at least the word. Now it applied not to semi-classical piano pieces but to anything that tapped into the jazzier rhythms: You syncopated not because you were required to by the dictionary definition, but simply as and when needed. And so Berlin pointed the way to swing, in the same way that in 1914 Jerome Kern's "They Didn't Believe Me" ushered in the forty years of timeless love ballads that form the core of the Great American Songbook.

Scholars understood "Alexander"'s specialness, but so did singers, and they kept it alive, even though it wasn't about boy-meets-girl, and its vernacular ("the bestest band what am") rang mighty odd even by the early Twenties. In 1938, Twentieth Century Fox built a movie around the song, Alexander's Ragtime Band, and a new generation of singers rushed to record. Bing Crosby & Connee Boswell won that battle, with "Alexander"'s second Number One hit, in September 1938. A decade later, Bing, the all-time duets champ, was back in the Top Twenty with a new "Alexander" sung with a new partner, Al Jolson - a wonderful, playful take that holds up very well. Sarah Vaughan & Billy Eckstine had fun with it, too, and Ella almost makes it work for the be-bop crowd:

Come on an' hear!

Come on an' hear!

Alexander's Modern Band...They can boo-be-doo-ye-doo-de-doo-de-doo-ye-doo-de-doo

So natural that you want to go to war...And if you care to hear the 'Swanee River' played in cool time...

And who doesn't? Although I'd have to say Ray Charles, without benefit of lyrical amendment, comes closest to making it play cool.

For most of the 20th century, American intellectual property law operated to very different principles from British Commonwealth and European law, and by the Seventies Berlin found himself in the bizarre and unjust position of having outlived the copyright on his first blockbuster hit. "Alexander's Ragtime Band" was still a popular song six decades after its composition, a situation few had foreseen in 1911 - not least its author. Asked to supply a poem on "The Popular Song" in 1913, Berlin himself had written:

Born just to live for a short space of time

Hated by highbrows who call it a crime...

But "Alexander's Ragtime Band" was still known and sung as it entered its fourth quarter-century, and even the highbrows had warmed up to it, and eventually, in the twilight of Irving Berlin's long life, US copyright law restored the author's rights to his own work - and to many other copyrights, albeit considerably less valuable.In 1912, for example, Berlin had written a sequel to his global smash:

Come on an' hear the bagpipes raggin' up a tune

In Alexander's Bagpipe Band

Come on an' hear McPherson actin' like a coon

In Alexander's Bagpipe Band...

Like its predecessor, the tune quotes Stephen Foster's "Swanee River" but this time throws in "Auld Lang Syne", and lets the lyric make sense of it all:

Should auld acquaintance be forgot on the Swanee River...

And so it would go for the next half-century. The two "Alexanders" encapsulate perfectly Berlin's entire career: Moments of genius alternating with Tin Pan Alley hack work. Few composers have written more bad songs, but few have written more good songs, and no one has written more hit songs. "Alexander's Ragtime Band" turned Ted Snyder's in-house novelty-song Alleyman into Irving Berlin, and Irving Berlin made himself the apotheosis of the American pop songwriter. "The alarm clock that awoke American popular music"? Well, it was certainly a kind of reveille - like the man said, "a bugle call like you never heard before":

Come on along

Come on along

Let me take you by the hand

Up to the man

Up to the man

Who's the leader of the band

And if you care to hear the 'Swanee River' played in ragtime

Come on an' hear!

Come on an' hear!

Alexander's Ragtime Band!

Happy hundredth birthday - and here's to the next century.