Someday

When I'm awf'lly low

When the world is cold

I will feel a glow

Just thinking of you...

On the radio the other day, Hugh Hewitt played (for his missus) Sinatra's recording of "The Way You Look Tonight" and then mused that he had no idea who sang it originally. So I put him wise: Fred Astaire to Ginger Rogers in the film Swing Time (1936). Then we got back to the usual stuff about immigration and jihad. But you'd be amazed how often the answer to "Who sang that song originally?" is Fred Astaire. He died 20 years ago this week - June 22nd 1987 - and without him the catalogues of America's greatest songwriters might be quite a bit smaller. He introduced a big chunk of the biggest songs by Jerome Kern, Irving Berlin, Cole Porter and George Gershwin. Of the five masters, Richard Rodgers was the only composer with whom his path never crossed, or not until a very late recording of "It's Easy To Remember". Kern, Porter, Berlin, Johnny Mercer, Burton Lane and many others considered him among the very best singers. And singing isn't even what he does. Or at any rate it's not his core activity. In the Seventies, he and Bing Crosby made a very charming album of duets, the recording of which was a breeze, except for a certain matter which weighed heavily on the producer, Ken Barnes. "I was worried about the billing on the album cover," Ken told me. "'Fred Astaire & Bing Crosby'? Or 'Bing Crosby & Fred Astaire'? And eventually I broached the subject with Fred, and he immediately brushed it aside. 'Oh, it's a record, it's singing. That's Bing's territory. He can go first.'"

Generous. But, while Bing certainly had more hit records in his day, it was Fred who introduced more lasting standards - "Fascinating Rhythm", "Lady, Be Good", "Dancing In The Dark", "Night And Day", "A Fine Romance", "Let's Call The Whole Thing Off", "They Can't Take That Away From Me", "A Foggy Day (In London Town)", "Nice Work If You Can Get It", "One For My Baby (And One More For The Road)", all the way to "Something's Gotta Give" from Daddy Long Legs in the mid-Fifties. There's a little cluster of songs that mention Astaire's dancing - "You're the nimble tread/Of the feet of Fred/Astaire" in "You're The Top", "Our homeward step was just as light/As the tap-dancing feet of Astaire" in "A Nightingale Sang In Berkeley Square". But his nimble vocal tread and his dancing pipes are as worthy of note. As Alec Wilder observed, "Every song written for Fred Astaire seems to bear his mark. Every writer, in my opinion, was vitalized by Astaire and wrote in a manner they had never quite written in before: he brought out in them something a little better than their best - a little more subtlety, flair, sophistication, wit, and style, qualities he himself possesses in generous measure." He certainly loved music and musicians, ever since, back when he was 17, he'd met a teenage song-plugger called George Gershwin at Remick's the music publisher in 1916. He wrote tunes (Tony Bennett recorded one of them, "City Of The Angels"), and he loved jazz: when he made a retrospective album of the songs he'd been associated with, he chose Oscar Peterson and the Verve stable's heppest cats to accompany him.

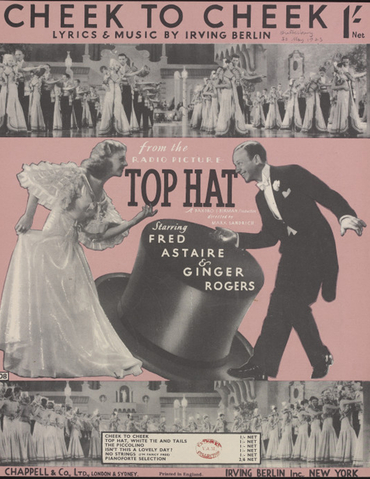

So, on this 20th anniversary of Astaire's death, how to honor his contribution to American song? "Top Hat, White Tie And Tails"? Well, it was Fred's uniform for much of the Thirties, albeit it a somewhat reductive one: He was very cool, but not always so bespoke. In my mind's eye, I see him in an open-necked shirt and casual pants held up by a necktie used as a belt. It was a great look, at least on him. And Astaire had a walk that could make the most crumpled trousers shimmer elegantly. It's true that "Top Hat", like "Puttin' On The Ritz", captures that rhythmic side of Fred: it's a number whose odd emphases are written with movement in mind. But there's a different kind of Astaire song - "blithe" is the word, the kind of tune that in its lightly worn ease captures the essence of romance. Often, it's about dancing - "Let's Face The Music And Dance", "Change Partners", "It Only Happens When I Dance With You", all three of which were written for Astaire by Irving Berlin. Burton Lane, the composer of an underrated Astaire score for Royal Wedding and also of Fred's last big film musical Finian's Rainbow (botched by Francis Ford Coppola), told me a few years back that no-one thought Berlin and Astaire would be a good match. "Irving was not considered a 'sophisticated' writer," he said. "He was supposed to be great for simple songs. But then he went to Hollywood and the songs he wrote for Fred Astaire were incredibly sophisticated, like nothing he'd ever written before."

In 1935 Berlin had been signed to write the score of Top Hat, the first purpose-built Astaire-and-Rogers vehicle and the one which established much of the template for the films that followed. The plot need not detain us long: Musical comedy star comes to London to star in West End show; his tap-dancing around the hotel room wakes up a gal on the floor below; complications ensue, aided and abetted by the Fred-and-Ginger repertory players - Edward Everett Horton as the bumbling producer, Eric Blore as the oleaginous valet, Erik Rhodes as the comedy Italian. The plot and the music reach their crescendo at a fantastically unreal Hollywoodization of the Lido in Venice, all art deco lily-pad islands linked by arched footbridges and archer waiters. At dinner Helen Broderick, who plays Horton's wife, suggests Astaire and Rogers dance. "Don't give me another thought," she adds breezily, which puzzles Ginger, who's operating under the assumption that Miss Broderick is married to Fred (don't ask, it'll take forever). Anyway, Astaire and Rogers take to the dance floor and for the first time Fred sings the words:

Heaven

I'm in heaven

And my heart beats so that I can hardly speak

And I seem to find the happiness I seek

When we're out together dancing Cheek To Cheek...

It's a deservedly famous dance number, but the song is of note, too: The plot requires Fred and Ginger to be in love, but for Ginger to be full of guilt and thus Fred to be endeavoring to overcome her misgivings. It speaks well for both parties that from an absurdly contrived situation they make something both real and magical. In four opening words, Irving Berlin nails the essence of the Astaire-Rogers partnership: its transportative quality. How splendidly confident to open with that one word "Heaven", like a wonderful sigh of content - and then to repeat it, with the thought filled out a little. Some musicologists compare it to Chopin's sixth polonaise (the A-flat major) with its "heaven"-like twice-declared descending major second, but really the character here is something all its own. And then Berlin takes the tune stepping up through "and my heart beats so", almost as if you're climbing even higher than heaven, and by the time Astaire gets to the words "hardly speak", Berlin's notes make the words very onomatopeic: It's clearly a reach for the singer, and something of a strange modulation, so that he seems to have literally entered a realm beyond speech. "The melody line keeps going up and up," Berlin said, recalling Astaire's treatment of the song. "He crept up there. It didn't make a damned bit of difference. He made it."

Berlin had never written anything like it before. It's long - not 32 bars, but 72, and in an unusual format - a 16-bar A section, repeated, then an eight bar middle section, repeated, then a bonus "middle", and finally back to the main theme for another 16 bars. Fred Ebb, the lyricist of Chicago and Cabaret and New York, New York, once took me through the song stage by stage. "Even in an apparently simple ballad, he chooses an 'eek' rhyme scheme, which is pretty difficult, I can tell you," said Fred. "Yet he still comes up with:

Heaven

I'm in heaven

And the cares that hang around me through the week

Seem to vanish like a gambler's lucky streak

When we're out together dancing Cheek To Cheek...

"It leaves you breathless," said Fred. That "eek" sound is an unlikely one for a romantic ballad. There's a reason songwriters use open-vowel sounds like "stars" and "guitars" in love songs: they're big and easy to sing. In less skilled hands, that "eek" could have killed the number dead. But Berlin liked it so much he kept the rhyme on for the rhythmic middle section:

Oh, I love to climb a mountain

And to reach the highest peak

But it doesn't thrill me half as much

As dancing Cheek To Cheek...

And then for the second "middle" section he junks all the analogy and metaphor and just lays it out, bold and ardent:

Dance with me!

I want my arm about you

The charm about you

Will carry me through

To

Heaven

I'm in heaven...

Very nicely done. And, on film, having expressed his desire to have his arm about her, Fred did just that. Berlin wrote the song in one day and, when he demonstrated it to the film team, they were unable to tell from his reedy voice and plonking piano whether it was any good. "The way he sang and played 'Cheek To Cheek'," said the choreographer Hermes Pan, "it sounded so awful." But not with Max Steiner's orchestration and not since.

On the day of shooting, I wonder if either Astaire or Rogers knew what they had. Fred was in white tie and tails, but Ginger was in a gorgeous gown of ostrich feathers. In the course of the dance, it shed - like a chicken attacked by a coyote, as Astaire put it. The feathers made him sneeze. Shooting was stopped. Every feather was sewn down into position and filming resumed, though in the picture you can still glimpse a few molting ostrich quills on the black laquered floor. As Astaire sang to Hermes Pan afterwards:

Feathers

I hate feathers

And I hate them so that I can hardly speak;

And I never find the happiness I seek

With those chicken feathers dancing Cheek To Cheek...

For years afterwards, Fred called Ginger "Feathers" and, when he and Berlin reunited at MGM for the 1948 film Easter Parade, Astaire included a recreation of the feathers incident in a dance with Judy Garland. Top Hat was a phenomenon. It was the second highest-grossing film of 1935, which is something to ponder: a guy prancing around the Lido in Venice in top hat, white tie, tails and tap shoes was bigger box-office than any rat-a-tat-tat Warner Brothers gangster picture. But it's not so hard to figure out. There's an aspirational quality about Astaire and Rogers. The plot contrivances, the foreign settings, the gowns and buttonholes, the art deco sets are, in the end, peripheral: when Fred has his arm about Ginger, they dance for everyone.

The song was a Number One smash on the Hit Parade, the first of the great dancing love songs Berlin wrote for Astaire. But how do you follow that? Berlin, brooding on a sequel to "Cheek To Cheek", decided simply to invert it:

Dancing Back To Back

Takes you off the beaten track.

You can see what goes on in the hall

When you dance Back To Back...

Oh, well. Back to back to the drawing board. But for Berlin, as for Kern and Porter and Mercer and the Gershwins and Dorothy Fields and Harold Arlen, the songs he wrote for Astaire were among the achievements he was proudest of. "I'd rather have Fred Astaire introduce one of my songs than any other singer I know," he told Hermes Pan. "Not because he has a great voice, but because his delivery and diction are so good that he can put over a song like nobody else."