If I know one thing about British comedian and actor Steve Coogan it's that nobody is lukewarm about him. Earlier this year Coogan played journalist and Labour MP Brian Walden in a Channel 4 drama about Walden's interview with Margaret Thatcher near the end of her reign as prime minister. To promote the series Coogan was interviewed by Emily Maitlis for the News Agents podcast, where he complained that the British establishment was intent on thwarting lower-middle class people like Walden, Thatcher – and himself.

While it's interesting to see a committed lefty like Coogan cite class to find common cause with Margaret Thatcher, James Innes-Smith of the Spectator wrote that he "found this so entertaining ... because you'd be hard pressed to find two more establishment figures than Coogan and Maitlis, and yet here they were intimating that they are the true outsiders, having to fend off a powerful cabal of upper-class twits."

Innes-Smith is baffled by Coogan's compulsion to play politics: "I began to wonder why he couldn't just stick with what he's good at. Isn't it enough to have played Alan Partridge, surely one of the funniest comic creations of all time? Why is he wasting time on political posturing? It's not what he's being paid for. He's a comedian."

Coogan, who has always bridled at being typecast thanks to the perennial appeal of Partridge (but inevitably returns to the role: a new series, Alan Partridge's How Are You?, has been filmed) is compared to talented actors whose career suffered or faltered in the wake of a signature role, like Harry Corbett of Steptoe and Son and Jon Hamm after Mad Men. But Innes-Smith writes that Coogan's "limited range is actually his greatest strength. As he approaches his autumn years it may be galling for him to admit that his talent rests on a single character, but there comes a time when every man must know his limitations."

And yet Coogan persists in sharing his political hot takes. Here he is recently on a New York subway channeling a sophomore common room radical, telling us that "Jesus was not a Republican" and that "Jesus was a socialist!" (It's always amusing to watch self-professed atheists declare their theological expertise. Look to see much of this as the Papal Conclave meets to elect a new Pope.)

But I'd argue that Coogan's need to have his political opinions heard is more than just the usual "clown nose on/clown nose off" celebrity eruption that overcomes comedians when they attain a palpable level of fame. I'd argue that it's crucial to the care and feeding of a comic creation more important to Coogan than Alan Partridge, which is Steve Coogan himself. And as evidence I offer The Trip, which was released in 2010 as both a BBC miniseries and a feature film.

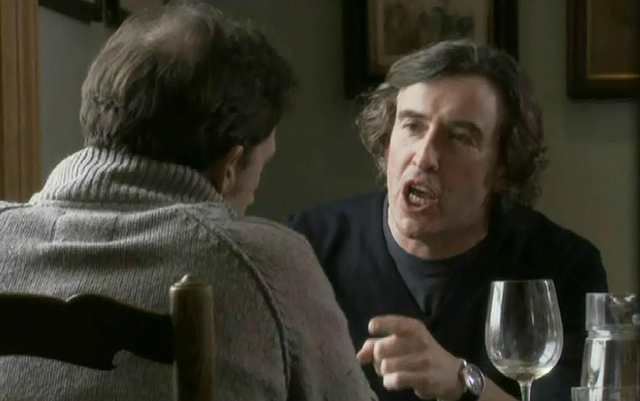

The film and series, directed by Michael Winterbottom, was successful enough to spawn sequels set in Italy, Spain and Greece, with a fifth (destination still unknown) due to start production this summer. The premise is simple: Coogan, playing a version of himself, is sent on a restaurant tour in some picturesque place in the company of his friend and fellow comedian/actor Rob Brydon, playing a version of himself. Not much happens besides a lot of driving, eating, walking and talking, but the films have created a devoted following that could see both men playing versions of themselves for as long as they're both able to hold a fork.

The Trip begins with Coogan phoning Brydon; he's been fired to take a food tour of the Lake District and write about it for The Observer and wants to see if he can come along. Brydon's first question is "Why me?" Coogan admits that he was supposed to do the trip with his American girlfriend, Mischa (Margo Stilley), but they've agreed to take a break from their relationship (he hints that it wasn't his idea) and that "I've asked other people but they're all too busy."

Coogan's tone delivering this last line suggests that these people might not have relished a solid week in his company, and that he's hurt but can't bear to go alone and validate their unspoken opinion of him. Brydon, by implication, isn't his first, or perhaps even second, third, fourth or fifth choice. They are drawn together, it would appear, not by mutual affection or even any real choice but as the men in their social circle whose flaws and status are suitably complimentary.

Brydon is happily married with a toddler, living in a renovated Victorian semi on a street of similarly renovated Victorian semis; Coogan by contrast lives alone in a flat in a modern building with floor-to-ceiling glass walls overlooking the city. The light in Brydon's home is warm while Coogan's condo is cool and blue. Before they begin their first dialogue scene their characters and circumstances are established neatly.

In his rented Range Rover, Coogan pulls out a bound book of road maps and says that he prefers plotting road trips on paper instead of a satnav. He says that it reminds him of family road trips as a boy. That they're talking about satnav instead of Google Maps is a yardstick of how the world has changed in fifteen years. Coogan also struggles to find cell service once they're in Lancashire, and is frequently forced to walk to the edge of lakes or the top of hills to find a signal, talking anxiously into his phone while surrounded by stunning vistas.

He has a lot to distract him on the trip: there's his estranged girlfriend, his ex-wife and his assistant Emma (Claire Keelan), as well as both a British and American agent charged with finding roles for him. He tells the British agent that he doesn't want to do any more British television and pleads with his American agent for prestige films with critically lauded directors.

His career is at a crossroads as he sees it, either about to take off or dissolve in entropy on the way back to dreaded obscurity. And Brydon's presence only aggravates his anxiety, as they're constantly comparing their career choices. At one point he tells Brydon that "you can't approach your entire life like a Radio 4 panel show."

"I'd rather be me than you," Coogan tells his friend. "A creature of mediocrity."

The simmering rivalry between the two men mostly expresses itself in celebrity impression battles. Brydon, who made his early reputation with his impressions and resorts to them frequently in his role as a game show compere, is shown relentlessly lapsing into voices (Ronnie Corbett is a favorite) to Coogan's exasperation, but during their first lunch they battle over their impressions of Michael Caine – one of the highlights of The Trip and one that would become an internet sensation and get ritually revisited over subsequent sequels.

Over another meal they duel over their James Bonds – limiting themselves to Connery and Moore, of course – and generic Bond villains. Their shared cultural frames of reference are squarely Gen X (both men were born in 1965). Early on, driving along a misty road through the moors, they belt out "Wuthering Heights" by Kate Bush as a hilarious baritone duet. Later Coogan launches them into a line-by-line dissection of Abba's "The Winner Takes it All"; Bryden tries to outdo Coogan with increasingly extreme exaggerations of Agnetha and Anni-Frid's ESL pronunciation but Coogan won't let him make a satire of the song – he finds it terribly moving.

Coogan is notably put out that Brydon seems happy to be a mere entertainer, famous within the confines of Britain and on TV and radio. It seems to make his own thwarted longing for success in the artistically acceptable quarter of Hollywood more difficult to endure. Brydon picks up on this; near the end of the trip he puts a "what if" question to Coogan, about trading a best actor Oscar in exchange for his child suffering a brief but curable illness. Coogan dismisses the idea with outrage when the stakes are just a BAFTA but has to think about it when an Academy Award is the prize.

The roots of The Trip go back eight years, to Winterbottom's 24 Hour Party People, a very loose biopic of Manchester TV personality and Factory Records founder Anthony Wilson, which starred Coogan as Wilson and featured Brydon in a small part Brydon. Three years later Winterbottom cast Coogan and Brydon in A Cock and Bull Story, his very meta film about the impossibility of making a movie out of Laurence Stern's 18th century novel Tristram Shandy with the men playing themselves when out of character.

During a lull in filming he noticed the playfully competitive dynamic between them and set up a situation for the two actors to completely improvise a scene together. It inspired the director to make The Trip, which frames largely improvised dialogue in a minimal but functional travelogue setting that turned out to be easily replicated. But none of it would have worked if the audience – or the British audience at least – wasn't familiar with Brydon and Coogan as public figures when they tuned in or took their seat in a theatre.

The Mancunian Coogan began his career doing voice work on Spitting Image before creating the overweening and shameless Partridge as a sports commentator for the Radio 4 comedy show On The Hour, landing himself in the middle of the fusion of cringe comedy and scathing satire created by writers and performers like Armando Iannucci, Chris Morris and Charlie Brooker. Partridge proved to infinitely adaptable, re-spawning in chat shows, sitcoms, news programs, radio shows, documentaries, podcasts and feature films, complete with a trademark catchphrase – the bellowed "A-Ha!" that dogs Coogan in The Trip. He has made Coogan famous, with fans who reasonably assume that the actor has come to invest an increasing amount of himself in the character over the years.

By contrast the Welsh-born Brydon struggled on radio until he made his name in the TV comedies Human Remains and Marion and Geoff at the turn of the millennium, the latter produced by Coogan's Baby Cow Productions. (Previous to 24 Hour Party People Brydon's filmography featured roles as "Man in crowd", "Bus driver" and "Traffic warden".) His profile was raised further with copious voiceover and narration work on cartoons, TV shows and commercials and as a guest on chat and panel shows, and since 2009 he's been the presenter on Would I Lie to You?. Barely known in America, he's a multimedia celebrity impossible to avoid in England.

While Brydon has a comparatively tame and uncontroversial personal life, with five children over two marriages, Coogan has been featured in controversies and scandals despite an expressed wish to keep his private life private. Married briefly in the early '00s, he's been involved with models and had a brief dalliance with Courtney Love; he's admitted to issues with drugs going back to the '90s and a deep dive into cocaine use. His celebrity put him in the centre of the phone hacking scandal that brought down the News of the World, and he's been outspoken in his contempt for the British press, calling for increased press regulation.

All of this informs the versions of themselves that Brydon and Coogan play in The Trip films, which slightly alter the circumstances of their onscreen personas with each film but maintain the basic characters they play – Brydon as affable if overeager for approval, Coogan as a man anxious to be taken seriously, a bruised ego constantly concerned with status and afflicted with imposter syndrome.

Coogan in The Trip suffers from troubling dreams. In one he's being hyped up by his L.A. agent, played by Ben Stiller, who tells him that he's "living the dream" and that the Coens, the Wachowskis and both Ridley and Tony Scott want to work with him – "all the brothers." In another he's walking to a news agent in a Lancashire village when a fan requests and autograph and asks if the rumours are true that he's a c*nt. Coogan tries to deflect the question but the man holds up a tabloid with the massive headline "COOGAN IS A C*NT SAYS DAD".

This was meant to segue into a musical number featuring Coogan and a group of locals dancing through the town while singing a Lionel Bart-esque ditty called "Everybody's a Bit of a C*nt Sometimes" but it was ultimately cut from both the series and the film (though it's available to watch on YouTube.) Still, it provides some idea of just how much less popular Coogan the man is compared to Partridge, his appalling but self-authored creation and de facto alter ego.

Over another one of the sumptuous lunches Coogan and Brydon share in the film (many featuring carefully plated and deconstructed dishes that embody the gastronomical trends in fine dining in the first decade of this century) Coogan complains that Welsh actor Michael Sheen is his nemesis, constantly getting chosen for roles he should be getting. Brydon replies that while this might be true, it doesn't change the fact the Sheen is far the more talented actor. No matter your opinion about Coogan, it takes peculiar nerve to portray such a plausibly disagreeable version of yourself for a public primed to see every flaw evoked or exaggerated by an intermittently hostile media.

Coogan and Brydon turn up late at Dove Cottage, onetime home of the poet Wordsworth, and are told by a docent that they've missed the last tour times. Coogan tries and fails to bully her into relenting but is stung when Brydon is recognized by the woman, who gushes over him and asks for an autograph for her grandson, who's a big fan of his "Small Man in a Box" routine.

Standing in a churchyard the two men ponder their deaths; Brydon asks if Coogan would show up to his funeral and cajoles him into delivering a eulogy, which is predictably harsh and critical. When Brydon is about to return the favour Coogan cuts him short and walks away. Mortality would become an even bigger issue with each subsequent installment in The Trip series, and begins when Coogan, queried by his friend if all his sleeping around is exhausting, replies that "everything's exhausting when you're past forty."

Your patience for The Trip films depends of course on how much you can tolerate of the real or fictional versions of Coogan and Brydon. The theatrical film edits might be sufficient for some people, while others will be happy to endure the six episodes of each miniseries. Others, of course, might think that even a little of Coogan is too much.

As an actor Coogan has a fondness for playing real people like Samuel Pepys, Stan Laurel, Tony Wilson, Martin Sixsmith, Mike McCarthy and Brian Walden, not to mention Soho pornographer Paul Raymond (in Winterbottom's The Look of Love) and even the monstrous Jimmy Saville (in the recent ITV miniseries The Reckoning). You could argue that he imbues all of these men with the same insecurity, but it's hard to deny that he's worked to live up to the estimation of his own talent held by his fictional self in Winterbottom's films.

Even putting aside the famously acid tone of British comedy, I've always responded to the portrayal of male friendship in The Trip films. On the surface pitiless and unsentimental – women often wonder if it's any kind of friendship at all – the dynamic between the fictional Brydon and Coogan rings true, at least to me. There's a gauntlet of candour and ball-busting that every man will run with a real friend, not because he craves approval but because the most valuable kind of friend will always be honest before anything else.

I can think of at least three friends in whose company I could happily endure an outing like Coogan and Brydon's tour of the Lake District, as likely to produce the same balance of sarcasm and genuine laughter if viewed from the same camera angles. And like Coogan and Brydon the full English fried breakfast at the end would be infinitely preferable to all the precious plates consumed on the way there. And just who would be Rob and who would be Steve would by necessity change from moment to moment.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.