Last week I wrote about Cary Grant's Mr. Blandings and his dream house, in a film released in 1948 during an international housing crisis, and just before the effects of the postwar economic boom started to be felt in the United States. This week we're fast forwarding fourteen years, to another middle-class American everyman played by another Hollywood icon, at the peak of that boom, trying to enjoy a whole hard-earned month of summer holidays.

Mr. Hobbs Takes a Vacation came out in 1962, the same year as the Cuban Missile Crisis, the last atmospheric nuclear test, the launch of the Telstar satellite and the death of Marilyn Monroe. It was the year before Beatlemania, and the year after Judy Garland's Carnegie Hall comeback concert, the defection of Rudolf Nureyev, the Bay of Pigs invasion and Mattel's introduction of the Ken doll.

The top grossing films of 1962 were The Longest Day and Lawrence of Arabia. The Billboard charts were dominated by the Twist, the Four Seasons, Ray Charles, Bobby Vinton and Neil Sedaka. The biggest Broadway show of the year was How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying and the New York Times bestseller list was topped by Franny and Zooey and Katherine Anne Porter's Ship of Fools.

The film begins with Jimmy Stewart's Hobbs in voiceover while a rocket leaves its launchpad, as he observes that "man is for the first time leaving the face of the Earth." (John Glenn would make his landmark orbital spaceflight in the Mercury capsule that year.) Cut to the same Mr. Hobbs stuck in traffic on his way to work, complaining that it's about time since "it's too damned crowded down here!"

Hobbs is a banker in St. Louis, and as soon as he arrives at work his secretary asks him how his vacation went; he responds by asking her to take dictation – a letter to his wife, to be opened after his death, explaining that while he believes that "the family is the rock upon which civilization is built" he would rather live underground "like a gopher" than endure another family vacation like the one they've just had.

Flash back to that vacation in its planning stages, and Hobbs arriving home to a nearly empty nest: his two oldest daughters are married with families of their own and their youngest daughter Katey (Lauri Peters) is 900 miles away at a private school. The only child left at home is Danny (Michael Burns), a TV junkie who spends all his free time watching westerns.

Hobbs wants to spend his vacation month with his wife Peggy (Maureen O'Hara) on a cruise ship while he ships Danny to a dude ranch to get his fill of the west. Peggy wants to gather all their children together in a beach house outside San Francisco on loan from some friends for a family vacation, and she talks over his objections so relentlessly that we know the cruise is off the table before the shot of Hobbs, Peggy, Katey, Danny, their Finnish cook Brenda (Minerva Urecal) and a month's worth of luggage crammed into their station wagon, driving west.

Their beach house turns out to be a late Victorian relic, its shingles, clapboard siding and trim the colour of driftwood. The interior is suitably antique – a haunted house in the making with water pumping machinery housed in an outbuilding and a party line on the phone constantly occupied by a biddy describing medical ailments in gruesome detail. The long economic slump of the Depression and the reallocated resources of World War Two had left America covered in "ancient" buildings like this, often poorly maintained; the Hobbs' reaction to their beachfront relic explains how eagerly cities swept their streets of architectural heritage around this time.

It isn't long before the Hobbs' older daughters arrive with their husbands. Susan (Natalie Trundy) and her husband Stan (Josh Peine) have hit a rough patch in their marriage after he lost his job and their two children are destructive terrors with no impulse control thanks to their permissive "never say no" parenting style. Worst of all is that their son Peter (Peter Oliphant), having nicknamed his grandfather "Boompah", has decided that he hates him.

Janie (Lile Gentle) is married to Byron (John Saxon), a university professor who's unable to speak to his in-laws without condescending to them. Both couples constantly cite psychologists and other experts to justify their indulgent parenting; Hobbs' only consolation is his belief that "in the long history of the world there's never been a child brought up right." (I learned long ago that the only certainty parenthood gives us is that we disapprove of everyone else's parenting.)

The screenplay for Mr. Hobbs was written by Nunnally Johnson, based on a book by Edward Street, author of Father of the Bride – another postwar tale of anxious parenting, turned into a box office smash by Vincente Minnelli in 1950. It was directed by Henry Koster, one of those journeyman directors beloved by studio heads, who had begun his career in Germany in the silent era as a screenwriter before moving to Hollywood and away from the Nazi government that had stripped him of his citizenship.

Koster made himself useful directing several of Deanna Durbin's pictures for Universal, but the highlights of his career include The Bishop's Wife (1947), Harvey (1950), The Robe (1953) and Flower Drum Song (1961). The soundtrack was written by Henry Mancini and it's full of his trademark riffing and jazzy orchestration.

At a glance – and aided by the poster campaign that featured chaotic collages and a bedraggled cartoon portrait of Stewart that looks like the work of MAD magazine artists like Mort Drucker or Jack Davis – you'd lump Mr. Hobbs in with any number of '60s "madcap" comedies like What's New Pussycat, The Party, How to Murder Your Wife and Cactus Flower. It's the kind of film I remember watching on cold, rainy weekend afternoons, stuck inside watching the American stations coming across the lake from Buffalo, New York.

Stewart's Hobbs frequently comments on the story with Walter Mitty-esque voiceovers, mocking himself and his ordeals. Koster also adds cartoon sound effects whenever Hobbs has to deal with the Rube Goldberg machinery of the water pump. But there are scenes where the director seems to be riffing on Jacques Tati with Stewart as Hulot, contorting his lanky frame and stooping as he endures the indignities and humiliations of his thankless labours in wordless scenes.

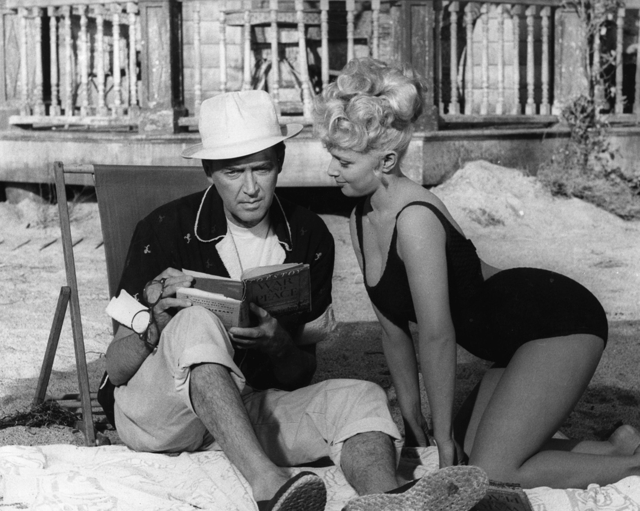

There are even feints at a sex comedy, mostly focused on Marika (Valerie Farda), the Hobbs' neighbour in the beach, a gold-digger modeled on the Gabor sisters, almost inevitably in a bathing suit. Finding Hobbs unresponsive to her interest, she shifts her focus to Saxon's Byron who, at least until Hobbs fabricates a story about her being potentially violent schizophrenic, seems responsive to her overtures.

And there's the persistent commentary on how O'Hara's Peggy is far too attractive to be a grandmother. (The actress was 41 when the picture was released. She'd played a more plausible parent the year earlier as mother to twin Hayley Mills' in The Parent Trap.) "36 – 26 – 36 and still operating," Hobbs says of his wife, who attracts the interest of Reggie (Reginald Gardiner), a fellow banker and the commodore of the local yacht club, as well as boys at the yacht club's "teen dance".

The film is billed as a comedy but it persistently hits a minor key whenever Hobbs and his wife are confronted with the generational drift in their family – a trend that Peggy was desperate to reverse when she planned their vacation together. "I can't figure what we did that was wrong," Hobbs wonders when they're all under one roof again but working to completely different agendas.

He says that he's only met Stan three times, and he and his wife admit to each other privately that they're not big fans of either of their sons-in-law. "I don't know these people," he complains to his wife, once they realize that their daughters, now mothers, are no longer the girls they remember, but he says that he's tired of them making all the effort to maintain communications with their grown children.

"Let them communicate with us for a change," he protests. Even more darkly Hobbs realizes that he's even less fond of his grandchildren, particularly hostile, destructive Peter, who he calls a "little creep". It's all pretty dark stuff for a comedy pointedly pitched at family viewing.

In 1962, 39.3 per cent of the U.S. population was under twenty; the majority of the Baby Boom had been born and the subsequent bust would begin a year or two later. While the Hobbs' older children were born in the early years of World War II, their younger children are definitely Boomers, and their attitudes are markedly different from their older siblings.

Danny's compulsive viewing of TV westerns is eerily similar to how videogame addiction is presented today; I have to admit to a twinge of sympathy as I was just as glued to the tube when I was a boy, though by the end of my teens I didn't own a television and wouldn't have one again for nearly twenty years. If they made the film today Danny's TV habit and obsession with sports trivia would likely get him placed on the autism spectrum.

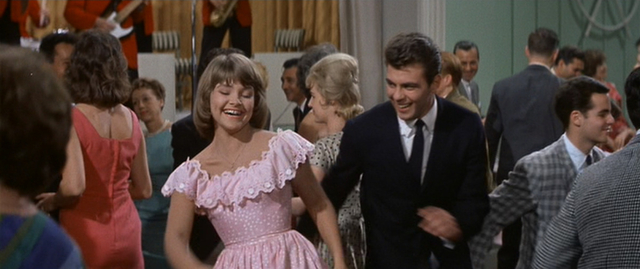

His older sister Katey by contrast is far more social but painfully self-conscious of her new braces. In the limited vocabulary she shares with her friends her parents are constantly called "weird" and judged to be ridden with insecurity and "complexes". The film goes on a foray into teen culture – or however such a thing was seen by men like Koster and Nunnally Johnson – when Hobbs gets Katey invited to a "teenager dance" at the yacht club.

The scene introduces the film's other marquee star – the pop singer Fabian Forte, known simply as Fabian. He was part of the crop of teen idols recruited after Elvis Presley was drafted, a cohort that included Bobby Vee, Bobby Vinton, Bobby Rydell, Frankie Valli and Frankie Avalon. Forte had his biggest success in 1959 with singles like "Turn Me Loose", "Tiger" and "Hound Dog Man", but by 1960 the hits had stopped and he shifted to acting, and in 1962 he had a part in The Longest Day as well as playing Joe in Mr. Hobbs.

He's a local boy who Hobbs pays $5 to dance with his awkward, wallflower daughter – to the insipid jump blues written by Mancini for the band at the dance. (Sharp eyes might spot trumpeter Herb Alpert on the stand.) Later in the film he's given the obligatory song - a duet to sing with Lauri Peters. "Cream Puff" won't make collections of Mancini's best work for good reason, but it's still a terrible earworm and you'll resent the film for planting it in your head.

The dance also lets us appreciate Stewart and O'Hara attempting the Twist, though the moment is cut mercifully short. It's undeniable that casting Fabian was an attempt to cover that massive under-twenty demographic, much as Saxon in bathing trunks was on the screen to cater to women over twenty.

Like so many '60s comedies Mr. Hobbs is episodic, as if it were a collection of TV episodes: there's one where Hobbs and his son bond when they get lost at sea in a fog while viewing an eclipse, and one where Hobbs and his wife have to entertain Martin Turner (John McGiver) and his wife Emily (Marie Wilson). Stan has applied for a job at Turner's company and convinces his in-laws to entertain the couple while on a road trip vacation.

Turner is a tedious eccentric who professes an austere lifestyle – a holdover from the early part of the century, his philosophy built from bits of Horace Greeley and Dale Carnegie. He exhausts Hobbs with a birdwatching outing and turns out to be a secret lush; he tries to take a swing at Hobbs when he's accidentally locked in the bathroom with Turner's wife but ends up with a bloody nose when the banker's patience is finally at an end.

I'm not sure if I can blame the episodic story or the abrupt shifts in tone, but Mr. Hobbs has pacing issues that makes it feel like sailing upstream in a marmalade river. (A reviewer at The Age in Australia wrote that "like nearly every Cinemascope comedy these days, is about half an hour too long.")

Mr. Hobbs Takes a Vacation was a respectable hit, earning back twice its $2 million budget before overseas sales. In response Johnson would write two more family comedies for Koster to direct and starring Stewart – Take Her, She's Mine (1963) and Dear Brigitte (1965). The film isn't mentioned as one of Stewart's best roles, though it's worth noting that the other film he made in 1962 was The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

Maureen O'Hara would work with Stewart again on the western The Rare Breed (1966), but wrote later that Stewart, though charming, could be an ungenerous co-star, afraid of being upstaged and willing to throw his weight around to get scenes re-written to favour him.

The Beatles would arrive in America at the start of 1964 and the generational anxiety that planted a sour note all through Mr. Hobbs would explode almost immediately. In hindsight, these glimpses of an uncertain cultural moment are probably the only things that make Mr. Hobbs watchable.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.