Mr. Blandings Builds his Dream House is remembered as a hit even though it lost money at the box office during its initial theatrical run. It's more accurate to say that the 1948 picture (and the book it was based on) was a cultural sensation, hitting a nerve with the American public during that anxious moment when World War II was over but nobody was confidently predicting a postwar economic boom that would last two decades.

When journalist Eric Hodgins published his comic novel in 1946, inspired by his disastrous attempt to build a home for his family in New Milford, Connecticut, hostilities had been over for a year but the United States hadn't been building homes for a decade and a half thanks to the Depression and the war. Millions of Americans, including returning servicemen and their families, were living in cramped conditions with parents or relatives, or in emergency housing in parks or on waste land.

It wasn't much different with allies like Australia and Canada (a row of emergency housing, now long gone, was built in the park at the bottom of my street), though the crisis was put into perspective by Britain's bombed cities, not to mention Europe and Asia, where vanquished enemies German and Japan and neighbouring countries that had been battlefields were in ruins. The titular Mr. Blandings might have been put through comic agony trying to build his dream house, but tens, even hundreds of millions of people were desperate for any kind of home.

The film begins, as the narration tells us it inevitably must, in Manhattan, where the narrator's paean to the joys and marvels of life in America's biggest metropolis is undercut with footage of traffic jams, crammed subways, teeming streets and standing room only lunch counters where businessmen wolf down lunch and gulp down coffee. In short order we meet one of those businessmen, Jim Blandings (Cary Grant), and his family – "modern cliff dwellers" as the narrator describes them, living in four rooms, high in an uptown apartment building.

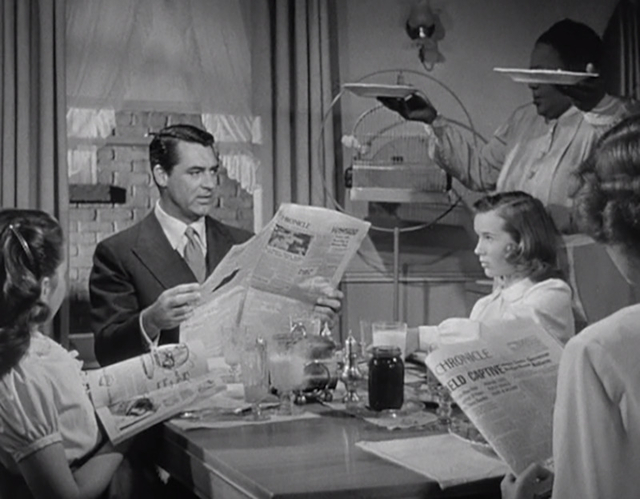

There's a bit of business where he tries to silence the alarm clock while his wife Muriel (Myrna Loy) turns the ringer on again before withdrawing it from his slumbering grasp. Grant, always a superb physical comedian, is followed on his morning routine as he tries to wash, shave, dress and eat as he deals with closets filled to bursting and a single washroom they have to share with two daughters, Joan (Sharyn Moffett) and Betsy (Connie Marshall), adolescents in that transitional age we now call "tween".

Jim Blandings works in advertising and his family are firmly ensconced in the middle class, their daughters enrolled in a "progressive" private school where they've fallen under the spell of its Jean Brodie – a "Miss Stellwagon" who has filled their heads with fashionable social pessimism and a budding contempt for the advantages of middle class life, and the whole business of advertising that employs their father and pays for their home and tuition.

In Hodgins' book, Betsy is concerned that her parents are considering buying what might be called a "colonial" house: "Miss Stellwagon says that sort of thing is a form of totem worship." The book version of Stellwagon is a progressive in the technocratic phase, who has convinced Joan that she should live in one of Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion houses: "It's built on a mast like a tent and it revolves with the sun. When it wears out you throw it away and get another one."

The children are also resistant to the country pursuits that their mother imagines undertaking. "I won't go picking blueberries and churning butter in any old country house," Betsy tells her. "We read about the division of labor last week. Shopping at the Supermarket is the most efficient way to –"

Jim objects to the authority of Miss Stellwagon invading his home, but his wife scolds him by saying that "there isn't any use sending the children to an expensive school and then undermining a teacher's authority in the parents' living room."

The line is copied verbatim in the movie, but the screenplay by Melvin Frank and Norman Panama (they'd later write White Christmas) replaces the girls' worship of technocratic modernism for disparaging remarks on "the disintegration of our contemporary society" and disapproval of "the crass commercialization of newspaper advertising."

It's strangely comforting to know that at least eighty years ago the middle class was sending their children to elite private schools that taught them to resent the privilege that made it possible – and paying top dollar to have their values undermined. Keep in mind that in 1948 a baby boom was only dimly anticipated, its cultural effect still unimaginable.

In Hodgins' book Jim Blandings' upward movement through Manhattan real estate is charted, beginning with a "little one-room-and-bath apartment for himself in the East Thirties," progressing to two rooms in the East Forties, upgrading to the East Fifties as a newlywed and shifting another fifteen blocks northward to the East Seventies with the arrival their first child.

While less happy with his job than their increasingly cramped quarters, success as an ad copywriter opens him up to social pressure amplified by his professional status. He could, if he wanted, move to another ad agency and take his prized clients with him, or even start an agency of his own, but he lacks that kind of ambition, and "if a business of his own did not tempt him," Hodgins writes, "something that he and his friends called 'the good life' did."

"Mr. and Mrs. Blandings realized that not only could they now afford to expand their modest horizons, but that, in the eyes of their professional colleagues, they could not afford not to."

The urge to upgrade settles on a house in the country – Connecticut, to be precise, and specifically a pre-Revolutionary War homestead that's been on the market for decades, long abandoned by the current generation of the Hackett family. They drive out to Lansdale County and into the hands of Smith (Ian Wolfe), a realtor who knows a sucker when he sees one.

In the movie Smith appeals to the Blandings to imagine how they could transform the Hackett homestead: Muriel pictures a cozy cottage inundated with rose gardens; Jim's mind conjures up a baronial hunting lodge. Neither of them can see the dilapidated near-ruin in front of them until it's too late and their offer has been accepted, which is followed by a parade of structural engineers who all agree that the best thing to do is pull the thing down.

Every bad decision the Blandings make is overseen by Bill Cole (Melvyn Douglas), Jim's "best friend" (the quotes are specified by Bill) and apparently a onetime college flame of Muriel's. He's also Jim's lawyer and rigorous critic of their impulsive charge at home ownership, and his instincts are unerringly correct, never more so than when they go ahead with demolishing a house on which someone else holds the mortgage, obliging them to pay it off immediately before they can proceed with building the home of their dreams.

They enlist Simms (Reginald Denny) as their architect, who designs a tidy neocolonial that's transformed into a hypertrophied collection of every mod con and feature the Blandings lacked in the city, not the least of which is a bathroom and closets for each family member. Retch (Jason Robards Sr.) is hired as general contractor and the epic construction project begins, during which rock is dynamited, and a well is dug for hundreds of feet just as water is discovered right beneath their basement floor.

The Blandings dream house is aspirational and reflective of their status; most American families desperate for housing after the war would settle for less, but first the country had to rouse itself to actually begin building. This meant forcing through a logjam in legislation that had been in place for over a decade, and saw a congressional hearing in 1947 where testimony was heard from people who had been doubling up with family members in cramped conditions, living apart from spouses and being threatened with eviction from social housing when their income rose, despite having nowhere to go even if they could afford it.

Eventually the 1949 Housing Act was passed, creating the conditions for a housing boom that saw the spread of suburban tract home developments like Levittown – a much more modest kind of house than the Blandings' dream home but sufficient to the needs and means of millions of Americans looking to escape conditions far less endurable than the Blandings' Upper East Side cliff dwelling.

Properties in Levittown were a far cry from the Dymaxion House but they were just as much a technocratic solution to the housing problem. They were, nonetheless, derided as dismal domiciles – engines of conformity described as "little boxes...all made out of ticky-tacky" by Malvina Reynolds in the folk hit performed by Pete Seeger in 1962, one of the most breathtakingly condescending songs to ever make the hit parade. One imagines the Miss Stellwagons of the world playing it for their students with approval.

Mr. Blandings Builds his Dream House was directed by H.C. Potter, one of those many competent contract directors whose reputation hasn't abided. His filmography isn't too shoddy and includes titles like The Shopworn Angel (1938) and Hellzapoppin' (1941), a surreal bebop musical that has to be seen to be believed.

Potter had the misfortune to direct The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle (1939), the film that ended the RKO partnership of Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire with a box office dud, as well as The Miniver Story (1950), the dismal and unnecessary sequel to Mrs. Miniver. He was blessed with the pairing of Cary Grant and Myrna Loy, who had demonstrated their onscreen chemistry in The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer (1947) after it survived the flop that was Wings in the Dark (1935).

Their charisma and star power was essential to play the Blandings, who are the authors of their misfortune at every step of building their dream house. Jim is the biggest offender, making decisions heedlessly and refusing to admit his mistakes, but Muriel contributes her share to the massive cost overruns. Her request to have a few slate tiles left over from the patio laid beneath her flower sink in the pantry requires tearing up and rebuilding the whole floor, rerouting of plumbing and electrical and structural changes that prevent several doors from closing properly.

Hodgins lays out the whole costly reconstruction over several pages in his book, and Potter eagerly replicates the scene in the film – a folly that involves every trade on the site, and which will resonate with anyone who's ever tried to depart a few inches from initialed plans while renovating anything from a broom closet to a bathroom.

The story of Hodgins' own dream house, and the inspiration for his novel, have a far unhappier ending than the book or the film, which ends with Grant breaking the fourth wall as he sits in his front garden with Loy and Douglas reading a copy of Hodgins' novel. His house was finished in 1939, after the initial budget of $11,000 had ballooned to $56,000 (respectively $253,078 and $1,288,399 today.)

He was forced to sell the house and later tried and failed to buy it back when he sold the movie rights for his novel to David O. Selznick and RKO. The house still stands today on a parcel of land called Blandings Way, which was sold off piecemeal over the years but reassembled by a neighbour in 2010.

The dream house built for the film on the onetime Fox Ranch still stands on the grounds of Malibu Creek State Park and contains administrative offices. But there were more Blandings dream homes: to promote the film RKO had 73 replica houses built all over the country in partnership with General Electric and gave them away in raffles. Kellogg's also offered a more modest miniature model complete with plans for 35 cents and a box top.

The appeal of the story of the Blandings and their dream house is easy to understand. George Washington Slept Here, a 1942 comedy starring Jack Benny and Ann Sheridan, has a not dissimilar plot, and it would be echoed years later in Please Don't Eat the Daisies (1960), starring Doris Day and David Niven. Mr. Blandings Builds his Dream House would be remade several times – as The Money Pit (1986) with Tom Hanks and Shelley Long; as Are We Done Yet? (2007) starring rapper Ice Cube; in Sweden as Drömkåken in 1993 and as La Maison du Bonheur in France in 2006. Grant and then-wife Betsy Drake would star in the radio series Mr. and Mrs. Blandings in 1951.

Home ownership is still a dream for many today, as a global housing crisis afflicts countries like Australia, New Zealand, Ireland and the UK, Austria, Japan, the Netherlands and elsewhere. Housing and immigration was set to be a major issue in Canada's federal election this month – until Donald Trump's tariff war delivered a big new winning campaign issue to Mark Carney, the globalist banker who recently replaced Justin Trudeau as head of the Liberal Party. The Liberals, who've never seen an election promise they couldn't ignore once elected, are likely to keep families and young Canadians dreaming about homes for at least another four years, and they won't consider it a comedy.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.