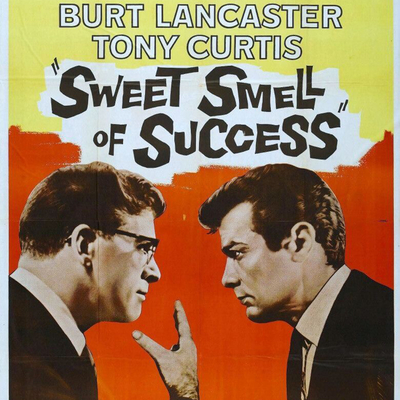

Last week's column talked about a movie with an unlikeable main character. This week I'm afraid it's more of the same, only this time our main feature is a film with not one but two unsavory protagonists, one of them a moral delinquent, the other a monster of immense self regard and power. The only relief is that Sweet Smell of Success is in glorious black and white, and set in wonderful, terrible mid-century Manhattan.

Alexander Mackendrick's film was a flop when it came out in 1957 but you wouldn't know it today; Sweet Smell of Success has made top movie lists in Sight and Sound, Time, Entertainment Weekly, the New York Times and the American Film Institute. It was chosen to be preserved by the Library of Congress and was given a deluxe reissue by Criterion. It has a 98% rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

That might make it look like the kind of classic film that you're supposed to take in like harsh medicine but it isn't. I don't know what audiences saw or didn't see when the picture came out but Mackendrick's film is a riveting portrait of awful people hustling each other to their just reward, beautifully shot and written with strong coffee for ink. You could say that they don't make them like this anymore, but I'm not sure they really made them like this back then.

The picture starts with what's probably one of the greatest New York City title sequences ever, and a showcase of the work of cameraman James Wong Howe, composer Elmer Bernstein and editor Alan Crosland Jr. It's Times Square before the Naked Cowboy and the grifters in Shrek suits, lit by neon and movie marquees that suffuse the sky with a twilight glow even well after dusk.

The bulldog edition of the New York Globe (standing in for the Times, with its offices right on the Square) is hitting the streets – the early version of the morning paper, back when the biggest of big city papers cycled through several print runs throughout the day, with presses that only stopped to change plates. And adorning the side of every Globe truck is an ad for their top columnist, J.J. Hunsecker, distilled to his spectacled eyes taking in all the action on the street.

The camera finally rests on Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis), waiting for the first copy to hit the newsstands, which he takes to read over his dinner at a hot dog stand. He searches for a page and his shoulders slump when he doesn't find what he wanted; he leaves half a hot dog on the counter and spikes the paper into a trash bin on his way to his office, just around the corner, in one of those low-rent buildings that would be home to porno producers and massage parlours within a decade.

Sidney Falco, we learn from the sign taped to the pebbled glass on his office door, is a press agent. He has a forlorn secretary suffering from an unrequited crush (the undersung Marie "Jeff" Donnell, who doesn't get much to do here except simper) and a bedroom behind the reception area; our first clue that Sidney's income is barely supporting his business. He's dodging calls from clients, including a jazz club owner who had been promised a mention in Hunsecker's column.

Sidney is in a bind; he's supposed to be pushing the club's main act, a quintet led by guitarist Steve Dallas (Martin Milner), who's being managed by Sidney's uncle Frank (Sam Levene). But Dallas is involved with Hunsecker's sister Susan (Susan Harrison) – a romance Sidney was asked to scuttle by Hunsecker in exchange for column inches. His girlfriend Rita (Barbara Nichols), a cigarette girl at the club, tells him that the lovers are in the alleyway.

Dallas has a quality that Sidney is unable to overcome – an upright integrity that has given Susan the courage to stand up to her controlling brother. It's a challenge that will test every ounce of Sidney's scheming and dissembling (qualities, we're told over and over, are defining to a press agent) but first he has to plead for another chance from Hunsecker.

Sidney finds Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster) holding court at "21" (a New York institution and victim of COVID lockdowns). It's an early stop on the rounds he makes as the city's top columnist, with a beat extending from Broadway to Hollywood to Washington – the latter embodied by the senator (William Forrest) sitting at the table with Hunsecker, in the company of a puffy-eyed talent agent (Jay Adler) and a pretty young singer he's managing (Autumn Russell).

We get a demonstration of Hunsecker's power watching the senator flatter the columnist, who curtly advises the senator not to let himself be seen in the open, in New York City, with a woman not his wife, obviously being procured by her so-called agent. Hunsecker barely looks at Sidney but lazily eviscerates his character in a series of cutting asides that Sidney's obliged to absorb without complaint in front of this audience.

Outside the club Hunsecker meets with Lt. Kello (Emile Meyer), his muscle on the NYPD, who knows and despises Sidney – a bitter judgment from a character who embodies official corruption at the retail level. Sidney pleads for and gets one more chance, which he promises to put into play that night, while Hunsecker is asleep, but he warns him that Dallas has proposed to his sister and that she intends to accept.

It was an open secret that Lancaster's J.J. Hunsecker was based almost wholly on Walter Winchell, once the most influential newspaper columnist in America, though his power was waning by the time Sweet Smell of Success was released – just after he'd moved from his televised radio show on ABC to a variety show on NBC. It was meant to compete with Ed Sullivan but was canceled after just 13 weeks.

Winchell was famously vindictive, printing items told in confidence by friends and turning on an old friend, singer Josephine Baker, when she criticized him for not taking her side in a dispute with the Stork Club over admitting black customers. He took on the U.S. Public Health Service in 1954 for its implementation of the Salk polio vaccine. He played himself or provided his voice on movies for almost four decades from Broadway Through a Keyhole (1933) to Daisy Kenyon (1947) to There's No Business Like Show Business (1955) to A Face in the Crowd (1957) to Wild in the Streets (1968).

Hunsecker's unhealthy obsession with his younger sister was a blatant nod to Winchell's infamous interference in his daughter's personal life, which saw him commit her to psychiatric institutions. (His son, Walter Jr., killed himself in the family garage on Christmas in 1968.) His early career was tied to several New York mobsters, but by his heyday he was a close friend of FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover, with whom he cooperated on targeted campaigns against celebrities and public figures. (Hoover would harass Winchell's daughter's lover into leaving the United States.)

Sidney's plan to take down Dallas starts with planting a blind item accusing him of being a Red and a weedhead in the column of one of Hunsecker's rivals. He starts with Bartha (Lawrence Dobkin), his closest competitor, and a man who had slept with Rita then threatened to get her fired. Sidney's attempt at blackmail fails when Bartha discovers unexpected backbone, admitting the infidelity to his wife before Sidney can make good on his threat.

He quickly moves on to Elwell (David White), a lecherous bottom feeder, using Rita as bait. He takes Elwell back to his office/crash pad where Rita is waiting and pimps her out in exchange for libeling Dallas. His master stroke is his certainty that Dallas' outrage will put him on a collision course with Hunsecker, who he advises to act conciliatory long enough for Dallas to bait him.

"To tell you the truth," Sidney marvels to Hunsecker, "I never thought I'd make a killing on some guy's integrity."

Hunsecker plays the injured party and gets Susan to break it off with Dallas but walks away incensed at the young man's audacity to criticize him as a bully and a phony patriot. He wants him "taken apart" by Kello and charges Sidney with the job, but the press agent recoils from the task until Hunsecker discovers his price and offers him his column to write while he takes Susan on an ocean cruise to repair their relationship.

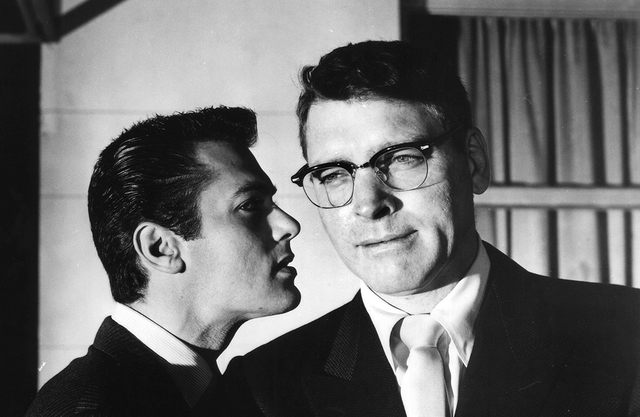

Tony Curtis needed a role like Sidney Falco to prove he was more than a heartthrob, and he rose to the occasion, even when sharing the screen with the famously ungenerous Lancaster, who was also the producer of the film. He'd been plugging away at Universal in pictures like The Prince Who Was a Thief (1951), The Black Shield of Falworth (1954) and The Purple Mask (1955) until he co-starred with Lancaster in Trapeze (1956), a circus picture.

Lancaster gave him the break he needed when they were casting Sweet Smell of Success, which was originally supposed to be directed by writer Ernest Lehman, who used his experience working as an assistant to a New York press agent in the orbit of Winchell to write the two short stories that inspired the picture's script.

Writing about the film for the Criterion reissue, jazz critic Gary Giddins says that "Curtis never softens the portrait, despite the few moments when Sidney stands up for himself, and he truly lets loose the rodent behind the 'charming street-urchin face' (J. J.'s description) in the pivotal sequence when Hunsecker confronts Dallas. Sidney is frequently compared to an animal, usually a dog (a 'trained poodle,' in Susie's emasculating phrase), and in this scene, he leaps about with his paws raised, cheering on the bully: oleaginous, childishly spiteful, and thankful not to be the butt of the attack."

Curtis' Sidney is described as "pretty" and "the boy with the ice cream face", though his charm is probably the only thing about him with any depth. Lancaster made him fight for space in their first scene together at "21", and he keeps it up for the rest of the film, battling against what Giddins describes as Lancaster's "minatory, semiviolent intrusions".

Lehman couldn't hold his own against Lancaster the producer, who in any case had no intention of letting the writer direct the picture. Lancaster saw something in the Boston-born, Glasgow-raised Mackendrick, who was looking for work in America after several career-defining comedies at Ealing Studios, including Whisky Galore! (1949), The Man in the White Suit (1951), The Maggie (1954) and The Ladykillers (1955).

Mackendrick's career after Ealing is one of the great "what ifs" of cinema: up till this point he had proven his talent, and the box office failure of his Hollywood debut was set off by its critical success; other directors had overcome this kind of failure, but Mackendrick never really recovered his momentum. He would be fired by Lancaster from The Devil's Disciple (1959) and replaced by Guy Hamilton and then replaced on The Guns of Navarone (1961) by J. Lee Thompson. He'd make three more films before leaving the industry at the end of the '60s to teach film in California.

Another reason for the longevity of Sweet Smell of Success is the rewritten dialogue courtesy of playwright Clifford Odets, who was hired when Lehman left the project to recuperate on a tropical island. Writing about making the picture in his book On Film-Making, Mackendrick admitted that he found Odet's dialogue "mannered and very artificial, not at all realistic," while acknowledging how it took inspiration from the "similarly preposterous style" of Damon Runyon's stories about the same milieu.

Odets told the director that "my dialogue may seem somewhat overwritten, too wordy, too contrived. Don't let it worry you. You'll find that it works if you don't bother too much about the lines themselves. Play the situations, not the words. And play them fast."

He took Odets' advice and made a film with dialogue that perfectly complements the heavily stylized New York noir of James Wong Howe's cinematography. The film is full of incredible, audacious lines that sizzle and smoke like coffee splashed on a griddle:

"You're dead, son. Get yourself buried."

"Match me, Sidney."

"My right hand hasn't seen my left hand in thirty years."

"Cat's in the bag and the bag's in the river."

"You sound happy, Sidney. Why should you be happy when I'm not?"

"Integrity. Acute. Like indigestion."

"You're blind, Mr. Magoo. This is the crossroads for me."

"Come back Sidney – I want to chastise you."

And my personal favorite:

"I'd hate to take a bite out of you. You're a cookie full of arsenic."

Sidney sets up Dallas by planting dope on him and leaving him to the tender mercies of Kello, who hospitalizes him. He's celebrating at Toots Shor's when he gets a call to meet Hunsecker at his apartment, but it's a trap set up by Susan, who pretends to be suicidal to stage what looks like a sexual assault, just in time for her brother to come home. She has, it turns out, learned well from men like Sidney and Hunsecker, and sets them up to destroy each other as she walks out of her brother's penthouse overlooking Times Square.

A hard ending to a harsh film built around two monsters slicing at each other and everyone around them with sharp words; it's not hard to see why it might not have been a home run like Peyton Place and Bridge on the River Kwai – the year's big hits. "Audiences in 1957 did not go to see Burt Lancaster and Tony Curtis movies to find the characters they played steeped in a disdain that also defiled venerable commonplaces of American life," writes Giddins, "from brotherly love to dogged ambition, not to mention newspaper columnists, cigarette girls, senators, the police, and all that glittered along the Great White Way."

Winchell certainly celebrated its box office failure, but his career was effectively over when the New York Daily Mirror closed in 1963, taking his column with it. Larry King, who took over Winchell's column at the Miami Herald, recalled later for the Chicago Tribune:

"You know what Winchell was doing at the end? Typing out mimeographed sheets with his column, handing them out on the corner. That's how sad he got. When he died, only one person came to his funeral: his daughter."

What most people know about Winchell today comes mostly from being a footnote to Sweet Smell of Success, and the film is often described as the culmination of so many film genres that had developed to maturity in the preceding decades – the film noir and the Broadway movie, the newspaper film and the jazz picture. And it's a film that would have us believe that near the end of the '50s a country made anxious by Reds and civil rights, juvenile delinquents and Sputnik found the time to be concerned about power-hungry newspaper columnists.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.