How hard is it to recommend one of your favorite films when the adjectives most used to describe it are "grim", "depressing", "bleak" and "harrowing"? Mike Leigh's Naked (1993) is described as a cult film, won several awards when it was released (including best actor and director at Cannes) and is inevitably called one of Leigh's essential films. But still – how do you feel good about telling people to watch a "feel bad" movie?

"This misanthropic gem," Mark Kermode said, introducing Naked for a Channel 4 screening "had become one of the most quoted cult films of all time...Most significantly, this is a film which forces us to spend time in the company of someone whose presence oppresses everyone."

Elsewhere in an introduction of the film for the BFI, Kermode calls it a "darkly apocalyptic comic parable" and "a nightmarish world in which everyone is isolated and the audience is never let off the hook." Writing about the film for Movieweb, Rose McQuirter called it "the best movie ever made about self-destruction," and Roger Ebert praised it, saying that it had "no plot, no characters to identify with, and no hope."

It's a film from the early '90s, at the dawn of Francis Fukuyama's post-Cold War "End of History", when one of the social effects of the so-called "peace dividend" was a surge in solipsism. The big enemies were gone, leaving us with the small ones – each other and, ultimately, ourselves. Naked might be the Citizen Kane of this unmourned moment. The original trailer promised a real comedy; I can only imagine the disappointment.

Our noses get rubbed in the dismal setting from the start, with a handheld camera tracking down a dark wet alley to close in on a couple having rough sex against a wall. By the time we're looking over the man's shoulder what started out as consensual has turned into rape; the woman breaks free and threatens the man with a beating from the man she's been cheating on. This is our introduction to Johnny (David Thewlis), whose face we barely see before he's on the run, back down the alley and out of town.

He steals a car – thoughtfully putting the folding pram back in the trunk before slamming it shut – and the motorway signs that play behind the credits tell us that he's on his way from Manchester to London. Abandoning the car by the roadside he makes his way to the only address he has in the city – that of his ex-girlfriend Louise (Lesley Sharp).

But before they can have a reunion Johnny makes the acquaintance of her flatmate Sophie (Katrin Cartlidge), and by the time Louise is home from work – she's the only one with a job – their introduction has been enriched heavily by weed and tins of Carlsberg. Louise and Johnny ended on a bitter note and his prickly, sarcastic manner doesn't repair the rift, so Louise goes to bed and leaves Johnny to take advantage of Sophie's hopeless crush on him.

Mike Leigh was born in 1943 and raised in Salford, the son of a doctor in a working class area; he would tell stories almost exclusively in working class settings when he switched from theatre to film with his first movie, the presciently titled Bleak Moments (1971). Writing about Leigh's upbringing in Your Face Here: British Cult Movies Since the Sixties, Ali Catterall and Simon Wells state that "growing up middle-class in a working-class area of Salford, Leight was instantly granted a simultaneous insider and outside status. 'I have a completely genuine knowledge about working-class life,' he says."

You could argue that this "outsider status" is a prerequisite for telling working-class stories, providing both perspective and license that anyone truly embedded in working-class life is denied. Naked, in any case, is less overtly about class than earlier pictures like Meantime (1983) or High Hopes (1988). While Johnny and Louis are plausibly working-class, many of the film's characters are less easy to pin down on Britain's multilayered but relentlessly codified class spectrum.

It's also less obviously political. Though far less in your face than Ken Loach (Kes, Raining Stones, Land and Freedom), his nearest contemporary, there's nonetheless a political component to nearly every Leigh picture. Naked, though, is a character study more than anything else, though if you were intent on nailing it somewhere on a political grid, the film delivers more than enough in subtext.

The film takes place in post-Thatcher Britain, and though Leigh and his cast and crew were anticipating a victory for Neil Kinnock's Labour in the 1992 general election, voters returned John Major's Tories to power and unwittingly set the stage for the coming rise of Tony Blair and New Labour. In the meantime, however, Leigh paints a picture of a London still as grimy and decayed as it was in the strike and blackout-plagued '70s.

He would return to this London in the '80s scenes in his later film Career Girls (1997) – a city of students and the unemployed, living in shared flats and bedsits on Dickensian streets lined with walls still streaked with coal smoke. (The contemporary scenes in Career Girls, however, very much reflect the city transformed not by nascent New Labour but the economy put in place by Thatcher, opposed every step of the way by people like Leigh.)

It's a pre-Britpop culture, where young people like Johnny, Louise and Sophie still wear shapeless overcoats, clunky boots and goth fashion, everything in black. The crow-like Thewlis actually lost weight living on coffee and cigarettes preparing for the role of Johnny, and his clothes hang off him while he wanders the city, his belongings in a duffel bag slung from his shoulder.

Driven to distraction by the clingy, needy Sophie and Louise's seething resentment at his sudden reappearance, Johnny flees their flat and heads out into the streets for the picaresque journey that makes up most of Leigh's film. His first encounter is with Archie (Ewen Bremner) and Maggie (Susan Vidler), two Glaswegian youth lost in London who moor themselves to Johnny while they try and find each other amidst the tea carts and crumbling archways of the nighttime city. They set the precedent for how Johnny will interact with most people – spewing a rapid fire monologue of facts and scornful interrogations to bafflement or indifference.

Thewlis ended up with the role after his first film with Leigh, a short called The Short and Curlies (1987) led to a brief appearance in Life Is Sweet (1991). Disappointed that all the work he'd done preparing for the latter film had been cut to some brief scenes, he'd been promised by Leigh that there's be something more substantial for him in his next picture.

The character Thewlis created during Leigh's trademark process of research, discussion and improvisation is defined by a keynote of hostility – a bright young man and autodidact whose intelligence has no outlet except for a barrage of sarcasm and invective, shot through with scorn and paranoia. "Johnny's not cynical," insisted Leigh. "He's despondent, he's disappointed, he's frustrated, but in fact he's an idealist, who's simply pissed off with cynicism and materialism. That's the whole complexity of what he and the film is about."

This is mostly revealed during his second encounter on his urban odyssey, with Brian (Peter Wight), a security guard who lets Johnny take shelter from the cold, grateful for company while he does his rounds guarding an empty office building. A reader and autodidact like Johnny, they get into an extended philosophical debate across the service corridors and empty floors, competing to showcase their erudition.

The genesis of Naked had come years earlier for Leigh, when he became interested in the apocalyptic tone around discussions of the impending end of the century, informed by Nostradamus and biblically inspired fear of rapidly approaching end times. The two men initially bond over shared misogyny – "whores and harlots" as Brian describes women, most notably his own wife, who he hasn't seen in thirteen years while she's living in Bangkok.

They pepper their conversation with references to the Book of Revelations, bar codes and "the mark of the beast", combined together into a rant that Johnny has no doubt rehearsed in his mind, employed to chip away at what remains of Brian's guarded optimism about the future – that of himself and mankind – none of which matters under the gaze of what Johnny describes as "a hateful God...a nasty bastard."

Good exists not to triumph over evil but to be defeated by it, again and again, in a pitiless world overseen by a cruel deity. "You see, Bri," Johnny says, "God doesn't love you. He despises you." It would have seemed more depressing if I hadn't done night shifts myself as a security guard just a few years before Naked came out, reading to kill the hours, just as eager to buttonhole other guards and passersby with similarly baleful and brilliant philosophical teardowns.

Also met along the way are two women, both of whom are worse for their brief meeting with Johnny. The first is a nameless woman (Deborah Maclaren) who Brian spies on every night, living in a tenement flat across from the empty office building. Johnny talks his way into her rooms, clearly intending to sleep with her and help that hateful God tear down what little is left of Brian's hope.

He discovers that she's older than she looked from across the street, an alcoholic whose trauma is both unstated and overwhelming. He flirts with her, picking through her little stack of cherished books, then devastates her by telling her that "you look like me mother." Maclaren's performance is affecting and nearly wordless, and the way her face registers his cruel dismissal is devastating to watch. Once she passes out he steals her books and leaves.

The second is a young woman working in a café (Gina McKee) who Johnny also charms into letting him into her borrowed flat. He's suitably grateful, but his gratitude only slightly slows the relentlessness of his corrosive patter despite the effort he's making at a connection. Leigh sets her up as a younger version of the woman in the window, depressive and alcoholic but further away from hopelessness, with enough of an instinct for self-preservation to kick Johnny out, back into the night.

While Johnny's on his urban odyssey, Leigh sends another man crashing into Louise and Sophie's life. Jeremy (Greg Cruttwell) – also called Sebastian – is a creature of the City, a Porshe-driving psychopath and rapist who's also apparently the landlord of the flat the two women are sharing with Sandra (Claire Skinner), a nurse on holiday in Zimbabwe. He lets himself into the flat looking for Sandra but comes across the vulnerable Sophie instead, who he plies with champagne and rapes before Louise gets home from work.

Jeremy looks like a non sequitur when we were introduced to him early in the film, and his sudden insertion into the main story is still baffling no matter how many times I've watched Leigh's film. He's a close cousin to American Psycho's Patrick Bateman, a walking satire of the status-seeking yuppie churl, but he's apparently there to remind us that, as bad as Johnny can be, he could be a lot worse.

"From a thematic point of view," Leigh said, "I felt it important for there to be a manifestation of unacceptable male behaviour in a way that upstaged Johnny, in order to put Johnny into some sort of perspective...I thought it was important that nobody should read Johnny as being raw, unadulterated negative male behaviour."

Looked at this way, Jeremy is a utility more than a character, and he serves not just to put Johnny in some sort of necessary context as the film's putative "hero", but to unite Louise and Sophie (and later Sandra, when she comes back early from Zimbabwe) together to protect themselves. But he is, both in Cruttwell's sneering performance and as a product of Leigh's creative workshopping, very much a caricature of an antagonist to the working class and a Thatcherite "creature".

Leigh's films are frequently applauded for their realism, but with a Jeremy walking across the screen it's hard to overlook all the other heavily stylized touches in Leigh's pictures. There's the dialogue, which has been shaped by the improv/rehearsal process and Leigh's background to a near-theatrical sheen, and all those character notes and tics – think of Alison Steadman's brittle giggle and Jane Horrock's sour squint as she spits out "fascist" and "racist" in Life is Sweet.

Leigh defends all this exaggeration and caricature, particularly with Naked's Jeremy. "Obviously there is an argument –" Leigh says, "which I don't accept – that there is no explanation as to why Jeremy/Sebastian is the way he is, but there isn't any explanation why anybody else is the way they are, eighter; people are presented as they are, from their background. The point is, there are these people around."

Which is easy enough to say, but it doesn't take away from how Cruttwell's Jeremy looks like he's walked onto Leigh's set out of a Harry Enfield sketch or an episode of The Young Ones.

At the end of his journey Johnny ends up running foul of the London's sinister elements. He attaches himself to a poster hanger who goes about his work impassively while Johnny's monologues become increasingly manic; his patience snaps and he puts the boot in – an eventuality that Johnny has been anticipating for most of the film. Finally he's set on in a narrow lane by a group of faceless and violent youth.

Limping back the only refuge he has in the city, Johnny's state dispels Louise's resentment, puts Sandra into professional mode despite her outrage at the state of the flat, and drives Sophie to a breaking point of self-pity and out into the street. He has a fit on the stairwell and reaches out to Jeremy of all people for sympathy. The film's arch villain, dressed in nothing but bikini briefs, takes in the distressing scene and pronounces judgment.

"Aren't people pathetic?"

With Johnny wounded and apparently deprived of whatever feral energy powers his scabrous logorrhea, everything subsides enough to allow Louise and Johnny to reconnect and rediscover whatever once brought them together. She decides she's done with London and is heading home, and offers to take him with her, back to Manchester to either find some solace or face up to the consequences Johnny had been escaping. Louise even sees off Jeremy with a kitchen knife and the threat of castration.

Despite the relentless despair of the film's tone up to this point, it almost looks like Leigh might deliver something like a provisional happy ending – he'd done it before and would do it again in other films. But Louise goes off to give notice and work and leaves Johnny with his mind and the habits it's formed. He tries to charm Sandra, who seems more immune than most of the other women in the film, but decides instead to steal the stack of cash Jeremy had left behind and heads out into the streets, hobbling and hopping painfully as the camera pulls away, leaving him behind just as it had discovered him in that first shot.

Fans and detractors of Naked will all admit that it lives up to its grim hype, and its success set up Leigh for bigger projects, which would, starting with Topsy Turvy (1999), a picture about Gilbert and Sullivan's D'Oyly Carte Company, come to include period films like Vera Drake (2004), Mr. Turner (2014) and Peterloo (2018).

It also launched David Thewlis' career from England to Hollywood, which has included parts in the Harry Potter franchise and the DC Extended Universe. But he's never equalled the intensity of Naked's Johnny, a part that reads as repellent on paper but plays onscreen as horribly human. There's good reason to believe that Leigh couldn't make the film today; even when it came out it was criticized for misogyny, and it's not like we're as receptive to context and intent today.

And it wouldn't help if Leigh tried to defend his picture, as he did back them, by saying things like "Naked certainly isn't misogynistic, tough, of course, Jeremy is not exactly a feminist. The film definitely and unashamedly deals with some unacceptable aspects of male heterosexual behaviour...There's no question that he (Johnny) has violence within him. I'm merely saying it's more complex than that. Frankly, I think it's very common male behaviour, and the way that a number of women respond to it in the film is not uncommon either."

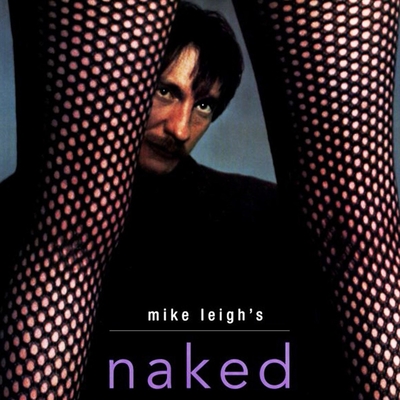

David Thewlis, Toronto, 1993. Photographed by Rick McGinnis |

When the film came out I certainly saw a lot of myself reflected in Johnny – not the sexual violence, but definitely the anger and misanthropy, the disappointed idealism, the default to hostility in social situations and the eagerness for confrontation. I think a lot of young men (I was almost thirty when Naked was released) did as well, especially if they felt marginalized by school and ill-suited to an office or a shop – places that, even then, were becoming dominated by more feminine energy.

I was assigned to take Thewlis' portrait when the film was released into theatres, back when I was working for a free weekly in the city with a famously progressive reputation (now defunct). Thewlis was a great subject, happy to take direction as I had him move all over the hotel suite booked for press interviews. Near the end of the shoot I told him how much I'd liked the film, and admitted that I'd seen a lot of myself and my life in Johnny.

"Oh," Thewlis said, a note of concern in his voice. "I'm sorry to hear that."

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.