Everyone can agree that films have become more violent, but nobody can say with certainty when this happened, or by how much. Similarly, there's a general (but by no means total) agreement that this is probably a bad thing, but there's no consensus as to how bad, or what should be done, if anything. There was a time when nobody talked about violence in movies, but lately there seem to be fewer people alive who can actually remember what that time was like.

This is my two hundredth movie column for SteynOnline, and I thought I'd take the opportunity to tackle a big subject instead of a single movie and look at a long period of movie history that roughly coincides with my own life. Sex and violence in the movies make us uncomfortable but, speaking only for myself, the former feels far more awkward to sit through, while the latter has to push the envelope pretty far to get me to take notice.

Movie critics often wring their hands about movie violence, mostly in attempts to make excuses for it as necessary creative brutality. "To fault films for forcing us to consider that humans commit atrocious acts, that evil exists in far too many hearts, is to blame the messenger," wrote Betsy Sharkey in the Los Angeles Times in 2013. "Whatever else the movies make me feel — horror, hubris, humor, humanity at its best and worst — I know it's real life, not Hollywood, that's the killer."

Younger film critics, like the ones who created this long form video essay, have even more complicated relationships to movie violence, having lived through the peak body count years of gruesome, realistic film violence. "It sounds awfully nice to justify torturing ourselves and our psyches with some of the most extreme violence we can access without crossing the barrier into real recordings by saying that we are becoming better, curing our inhibitions; that's all it is – talk," one of them states for the camera, while costumed as the victim of some onscreen massacre, slumped against a blood-painted wall. "At the end of the day we are softening ourselves to atrocities,"

There has always been violence in the movies, from gangster films, westerns and war pictures to film noir, dramas and slapstick comedy. But the first six decades of the American movie industry was notably restrained in its depiction of onscreen violence: virtually bloodless, with most deaths occurring out of the frame, the extras felled in shoot-outs or battle scenes clutching their chests and pirouetting to the ground – ridiculous, to be sure, but a comforting nod to the audience that it's all staged, with an aesthetic that went back to Victorian theatre.

The 1930 Motion Picture Production Code had more to say about dancing than violence, as a document more concerned with social morality in general and sex in particular. "The presentation of murder is often necessary for the carrying out of the plot," it states in a single relevant section. "However," it continues, "a) Frequent presentation of murder tends to lessen regard for the sacredness of life. b) Brutal killings should not be presented in detail. c) Killings for revenge should not be justified i.e. the hero should not take justice into his own hands in such a way as to make the killings seem justified. This does not refer to killings in self defense. d) Dueling should not be presented as right or just."

Like everything else in the Code, it was left up to producers, directors and writers interpret what that meant in a watchable movie, and it's obvious that the Code was selectively ignored from the moment it went into effect, and that by the early '60s it was dying on its feet. This is the moment when everything changed.

The Chase (1966) Nearly every history of the era of modern movie violence begins with Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde (1967), but I'd argue that it began a year earlier, with this Penn flop starring Marlon Brando, Robert Redford and Jane Fonda. The film doesn't really break a lot of ground with its story – a classic tale of a small southern town drowning in its own hypocrisy, its citizens goaded to make a scapegoat of Redford's local boy escaped convict when he makes an unwilling homecoming.

Brando, playing the sheriff considered in the pay of the local oligarch (E.G. Marshall), has to assert his independence in the face of the mob and gets soundly beaten in his own office by a trio of men led by Richard Bradford. It's a long, agonizing scene, and Brando is already down for the count when it starts, struggling to get back to his feet and get in a punch before being pummeled mercilessly, ending up covered in blood, lying on a desk and rolling off to the ground like a side of beef.

The sadism was unprecedented, and Brando was fully committed to making us wince with every blow, suggesting to Penn that the punches be delivered slowly and speeding up the film later. It doesn't play out like a choreographed fight or saloon brawl; it plays like real violence, and if you've ever witnessed a real beating it rings true, right down to one of the men pulling Bradford off Brando before assault turns into murder. It changes the tone of the film, and doubtless provided Penn with an idea how an unflinching depiction of what bullets do to a body would make his story about a legendary outlaw couple vault out of decades of gangster pictures.

The Wild Bunch (1969) Director Sam Peckinpah is the colossus figure in Hollywood movie violence, a trailblazer whose films changed how violent action would be shot and edited forever afterward. A Monty Python skit from the third season of the show – "Sam Peckinpah's 'Salad days'", in which a British upper-class day in the country descends into fountains of gore and body parts – sums up public perception of the Peckinpah effect on movies. (The director loved the skit and would play it for friends.)

After studio interference bowdlerized his original vision for Major Dundee (1965), the director was hell bent on making The Wild Bunch his way. The film is bracketed by two long action sequences, the first an ambush gone wrong between a gang of outlaws and railway gunmen during a temperance parade in a Texas town, the second a climactic battle between the remaining outlaws and the Mexican army. The first is pure chaos, the street littered with more innocent bystanders than gunmen, the last an epic and suicidal battle that leaves almost no one left alive.

The Peckinpah "ballet of blood", where gore erupts into the air while bodies fall to the ground in slow motion, would change both big budget movies and low budget exploitation pictures were made. Peckinpah was heavily influenced by Kurosawa and other Japanese directors, but The Wild Bunch would steer westerns, already well in their revisionist phase, to a pitiless and morally unmoored landscape from which it would never return.

A Clockwork Orange (1971) The poster for Stanly Kubrick's movie adaptation of (most, but not all of) Anthony Burgess' 1962 novel tells us that Alex (Malcolm McDowell), the film's protagonist, is interested in not mere violence but "ultra violence". It's difficult to underestimate the importance of A Clockwork Orange on filmmaking, pop culture and subcultures, but it has to be remembered how it caused a moral panic – the first of many that went from the public to the media to government, voicing fears that copycat fans would migrate violence from the screen to the real world.

The film is precisely what the authors of the Code worried about back when sound was still the newest innovation in pictures. Alex is a psychopath in a sociopathic society, a dystopic Britain full of brutalist housing estates where the youth cultures created by postwar teenagers have bred outlandish gangs fighting constant turf wars. Kubrick's innovation was to update the book's pre-Beatles "mods versus rockers" setting to a post-psychedelic city that enables and indulges vicious thugs like Alex and his "droogs" with consumer goods and semi-legal drugs.

Kubrick's decision to stylize the action and follow Alex around as if he was the story's unironic hero produced a string of set piece scenes that culminate in a home invasion/rape – the infamous "Singin' in the Rain" sequence. Alex' creative expression is violence, and in a society that no longer seems like it can educate young people to choose goodness – psychological brainwashing is the best it can do to cure Alex of his psychopathy – his is the only kind of rebellion left against what can only be described as the worst tendencies of Wilson's Labour and MacMillan's Tories to both control and remake Britain in their dismal image.

It's not surprising that making a film where the moral centre is deliberately skewed – if it can be found at all – was an exercise bound to make trouble. Kubrick likely knew he'd been playing with fire and he withdrew the film from exhibition in Britain after it inspired copycat crimes, and it would remain unavailable until his death in 1999. The film nonetheless resonated as a deliberately provocative totem in glam, punk and new wave culture for years to come, a challenge for anyone who "got the joke." I had the film's poster on my wall as a teenager.

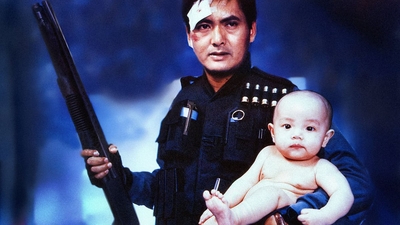

Hard Boiled (1992) It would take two decades after Peckinpah for anyone to come up a really new idea in movie violence, and it would come from Hong Kong, where martial arts pictures had refined state of the art action. Starting in 1986 Woo began making a series of crime thrillers that took the energy of kung fu cinema and expressed it with guns and bullets. I could include any of four Woo pictures – A Better Tomorrow (1986) and its sequel A Better Tomorrow II (1987) as well as The Killer (1989) – but I've chosen the last film he made before "going Hollywood" because it's the one I saw first.

Besides his wild, scenery destroying action sequences – dubbed "bullet ballet" in recognition of their innovation on Peckinpah – Woo's innovation was a matter of character and tone. His heroes – usually played by Chow Yun-Fat or Tony Leung Chiu-wai, both of whom appear in Hard Boiled – aren't the stoic, squinting gunslingers of Hollywood westerns or action films but men consumed with doubt and regret, desperate for connection and a moral anchor in the place where police work and crime meet.

Woo's violent action scenes are even more stylized than Peckinpah's, deliver massive body counts and form the foundation of the "gun fu" fighting showcased at its pinnacle in the John Wick franchise. The showpiece of Hard Boiled is an epic shoot-out in a hospital, where Chow and Leung move from floor to floor, emptying endless magazines and upgrading their weapons like a first-person shooter, evacuating patients and saving babies before the mob armoury in the basement blows up. You have to see it to believe it.

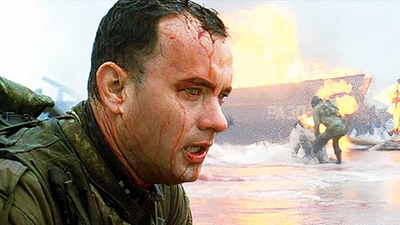

Saving Private Ryan (1998) It's often said that the most realistic war film would be unendurable: hours and hours of tedium and waiting leading up to a sudden, furious explosion of violence and chaos at deafening volume that would traumatize viewers. After nearly a century of war movies Steven Spielberg ended up coming as close as possible with the opening D-Day scene of Saving Private Ryan.

The film begins with an aging veteran visiting one of those cemeteries in France planted with endless lines of white headstones, of men who died within minutes, hours or days of each other. It's a warning, and the camera cuts to Capt. Miller (Tom Hanks) in a Higgins boat heading for Omaha Beach. The ensuing scene was as realistic and accurate as $12 million and four weeks of shooting could manage (the incorrect German pillbox notwithstanding). Movies had tried to tell this story before – most notably of all The Longest Day (1962) – but technical limitations and moviemaking conventions had made them come up short.

Saving Private Ryan used state of the art practical effects and careful digital infill to provide a "you are there – God help you" experience of battle, its tone set by adrenaline and terror. From this point on nobody could think about depicting war on screen without striving to meet the high bar set by Spielberg. Hanks and Spielberg would take the innovations and lessons they learned here to produce landmark WW2 miniseries like Band of Brothers and The Pacific and nobody would ever sit down to watch a war film again without knowing that few of the soldiers we meet in the first ten minutes will be there by the credits.

Oldboy (2003) Park Chan-wook's Kafkaesque story centers around Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-sik), a pathetic alcoholic salaryman kidnapped off the street and kept prisoner for 15 years by an unknown enemy. His captors frame him for the murder of his wife and heal him after his suicide attempts, keeping him alive on fried dumplings. After nearly a decade his madness gives way to resolve, and he begins training himself for when and if he can escape or get released from the hotel-like prison where his only view of the world comes from a single window and a TV.

One day, tantalizingly near realizing his escape plan, he's released on the roof of a high-rise building where the first person he meets is a suicidal man. Oh Dae-su is never more than minutes away from insanity, especially after his captor contacts him and issues a challenge: discover his tormentor's identity or they'll kill Mi-do (Kang Hey-jung), the young sushi chef who took him in after he ate a live squid in her restaurant and passed out.

The plot of Oldboy is essentially a nightmare, but its violent innovation comes in the scene where Oh Dae-su discovers the hotel where he was imprisoned and is forced to fight his way out through a throng of gangsters, armed only with a hammer. It's a shocking departure from action film conventions, with the camera shooting mostly in a long shot showing a cross section of the building while Oh Dae-su takes unbelievable punishment, battering his way through his assailants, arms windmilling with fury. It was shocking to discover that, after over three decades of steadily escalating movie violence, there was still an original angle available.

Bronson (2008) Tom Hardy might be the quintessential actor for the modern era of movie violence. There are plenty of contenders, to be sure (Jason Statham, Mark Wahlberg, Chris Evans, Vin Diesel, Jon Bernthal, Alan Ritchson, Henry Cavill) but Hardy seems uniquely equipped and temperamentally suited to embodying every kind of man of violence, which he's made a specialty across films like The Dark Knight Rises, Mad Max: Fury Road, Lawless, Venom, The Drop, Legend (playing both of the Kray twins), The Bikeriders and many more.

Solidly built, with a pugilist's broken nose (he competes in Brazilian jiu-jitsu), Hardy looks more than capable of absorbing and dealing out punishment, which made him perfect to play the most notorious prisoner in the British jail system – Charles Bronson (born Michael Peterson), a sociopath considered Britain's most violent criminal. Hardy devoted himself to the role, visiting Bronson in prison, bulking up and perfecting an impersonation of the convict so good that Bronson shaved off his trademark moustache and sent it to Hardy so he could wear it in the film.

Nicolas Winding-Refn's picture loudly echoes A Clockwork Orange, with stylized violence and theatrical fantasy sequences where Bronson imagines himself telling his life story to adoring theatre crowds. But the terrible heart is Hardy's Bronson, who considers violence his great talent and, learning how ill-suited he is to life outside prison, devotes his brutal energy to provoking his guards and the whole system into displaying his art. The film is essentially a series of fight scenes, each one a showpiece for Bronson's awful creativity.

The Equalizer 2 (2018) Revenge stories are currently the hottest type of violent action picture, a thriving genre that includes franchises like Liam Neeson's Taken films, Keanu Reeves as John Wick, and pictures like The Beekeeper, Wrath of Man, Nobody, The Accountant, Upgrade, Promising Young Woman, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and countless other films that basically rewrite a formula that was already refined to near-caricature with the Death Wish films in the '70s.

After Denzel Washington proved his action hero credentials with Tony Scott's Man on Fire (2004), director Antoine Fuqua took an '80s TV series and rebuilt it around Washington as Robert McCall, a retired special ops agent trying to live incognito in Boston but forced to use his special skill set to help get justice for the otherwise helpless. The first film pits him against corrupt cops and the Russian mob, but by its sequel he's forced to take on a group of former co-workers who've turned mercenary.

McCall's superpower is his focus – the films hint that it might have its roots in autism – and the films' action set pieces involve the camera zooming in to Washington's eye as McCall calculates every threat he faces and sets a timer on his watch to give him a goal to beat. In The Equalizer 2 he faces down a luxury hotel suite full of arrogant young suits who've drugged and assaulted an intern. Beady-eyed and cruel-faced, they think this old Lyft driver will be a pushover, but he leaves them broken and bleeding; they were straw men villains, but the scene is still immensely satisfying, as is the film's premise that an old man can beat those kind of odds.

Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood (2019) It's impossible to make a list like this without mentioning Quentin Taratino, much as I tried. As a filmmaker I'm more irritated by Tarantino than anything else, and while he's the film geek who wrote his own ticket through Hollywood you can't help but admire him even if every film he's made since Reservoir Dogs has either collapsed under the burden of self-indulgence (The Hateful Eight, both Kill Bill films, Inglourious Basterds) or barely stayed aloft thanks to a few brilliant scenes and performances (Pulp Fiction, Django Unchained, Jackie Brown).

Unlike myself, Tarantino truly loves movies and has forgotten more about them than I'll ever know. Most of the time this knowledge is a barrage of homages and tributes and outright rip-offs, but with his last film he managed to churn this annoying erudition into a love letter to Hollywood and Los Angeles in its last moment of pure, golden, sun-kissed potential. He does this by imagining that Steve McQueen hit the skids after The Great Escape, and recasts him as fading movie star Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio), desperately looking for a comeback, helped by his stunt double Cliff (Brad Pitt).

Rick's neighbours on Cielo Drive in Benedict Canyon are a young starlet named Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) and her husband, a young Polish director. But after bookmarking this impending tragic subplot, Tarantino diverts into a fantasy, imagining that Charles Manson's hippie hit squad decided to pay a visit to Dalton instead of Tate, to be met by Cliff, tripping on acid but still very capable. Intent on delivering catharsis onscreen, Tarantino has Cliff brutally neutralize Manson's minions, letting Dalton get the coup de grace with a flamethrower. It's a terrible, wonderful ending and you'll probably be able to live with the odd pang of guilt for wishing it could have happened.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.