There were probably as many westerns on TV as movie screens by the last half of the '50s, when the genre mutated from the oaters of the '30s and '40s to the revisionist films of the '60s and '70s. They were often being made by the same directors and crews, on the same sets and locations, with casts who moved from big to small screen to make a living.

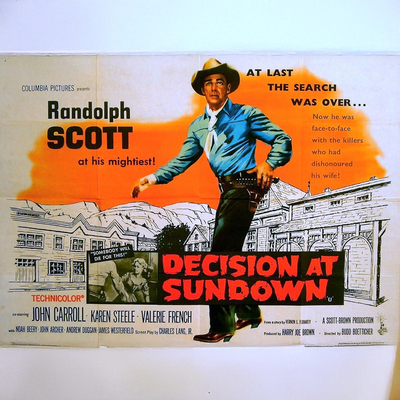

It's why a film like Budd Boetticher's Decision at Sundown (1957) has been described as looking like an episode of Gunsmoke, which hit the air two years previous and would run for two decades. Boetticher himself directed several episodes of Maverick for ABC that year and after finishing what would later be called his "Ranown Cycle" of westerns (of which Decision at Sundown was the third) would direct episodes of Death Valley Days and The Rifleman.

But TV westerns were still being made for the TV market, with all the restrictions that entailed. Describing them in The Western from Silents to the Seventies, George Fenin and William K. Everson described them as "designed specifically for juvenile audiences, but needing adult approval (since it would be the adults who would buy the produces advertised by the show's sponsor), the films succeeded in providing action and simple comedy, avoiding elements such as sex, strong drama, or brutality, which might alienate viewers supervising their children's entertainment."

Decision at Sundown would never have made it to air as an episode of Gunsmoke, for reasons that will be obvious. Boetticher himself described his '50s westerns as "C movies" meant to play on double or triple bills (it's an economical 77 minutes long) in markets outside the big cities, ignored by movie critics at city broadsheets, to audiences unlikely to complain about a feint at adult themes or a bit of extra violence that defied the Production Code.

The film begins with what looks at first like that most venerable of western plot points – a stagecoach hold-up. When Bart Allison (Randolph Scott) pulls out his revolver and makes the driver stop the coach he's riding in in the middle of nowhere, you assume that he and whatever party he's waiting for will relieve his fellow passengers of their valuables and whatever might be in the inevitable strongbox.

But Bart tells the driver to keep going (after relieving him of his rifle) when Sam (Noah Beery Jr.) comes riding out of the trees pulling an extra horse. Sam is another venerable western trope – the comic sidekick, best friend of the man we presume will be the picture's hero.

Bart has business in Sundown with a man named Tate Kimbrough (John Carroll), and Sam has scouted the territory in advance for him. Tate has done something wrong to Bart and he's intent on revenge, but Boetticher and screenwriter Charles G. Lang (working from a novel by Vernon L. Fluharty) take their time letting us know the what and wherefore.

They arrive in the town of Sundown where Sam will be frustrated in his sole ambition – to get a square meal after living in the woods for two days; it's the single comic note he's meant to play for the whole picture. Beery was from an acting dynasty that included his father, whose career lasted from silents to sound and included pictures like The Mark of Zorro (1920) and She Done Him Wrong (1933), and his uncle Wallace Beery, a major star at MGM in the '30s.

Beery's Sam treads in the well-worn footsteps of western sidekicks like Gabby Hayes, Walter Brennan, Smiley Burnette and Al "Fuzzy" St. John. His needs might be simple compared to the protagonist but he's not daft or cowardly; he's able to watch Bart's back as things kick off in Sundown and because the stakes seem a bit higher, you get the uncomfortable intimation that he might not survive to the last reel.

Sundown is run by Kimbrough, who arrived there two years earlier and took it over with the help of his own gang of decidedly non-comic sidekicks, principally Swede (Andrew Duggan), officially the sheriff but known to everyone in town as "Kimbrough's man". If they had any competition, it would have been the rancher Chase (Ray Teal) and his cowboys, though they seem to have been beaten under by Kimbrough.

And there's Dr. Storrow (John Archer), who arrived in town before Kimbrough took over and longs for it to return to the civic paradise he remembers. He's meant to serve as the moral centre of the picture since, as it gradually transpires, the Randolph Scott hero at the top of the credits isn't filling that role.

And there's Ruby (Valerie French), Tate's girl, who we first see together as he's getting dressed in her hotel room – a post-coital moment meant for adults to notice. She's a worldly brunette dressed in fine city clothes, and while she's never given the profession that's usually the code for prostitute or madam (like music hall dancer or saloon manager) the inference is there, and underlined by how dismissively Kimbrough treats her.

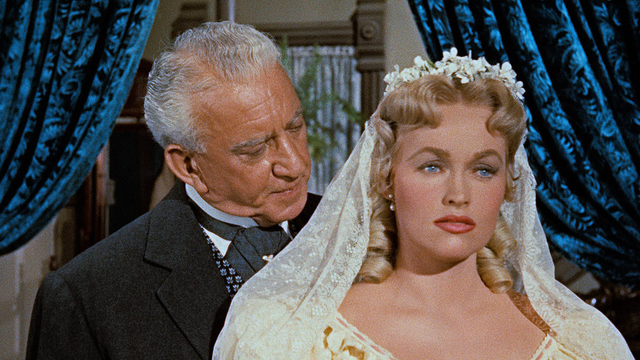

He's especially dismissive because it's his wedding day. He's set to marry Lucy Summerton (Karen Steele), the blonde belle of Sundown and daughter of Charles Summerton (John Litel) it's leading citizen. It's a coup for Kimbrough, as it will legitimize his control of the town with the added benefit of marrying him to the resources of its richest citizen – a good deal for everyone, if more than a bit mercenary.

Boetticher had met Steele while directing the first three episodes of Maverick, and they would become a couple though never married – an apparently tempestuous relationship, though she would end up starring in two further Ranown Cycle films, Westbound and Ride Lonesome, before they split up.

The Doctor, it's implied, is carrying a bit of a torch for Lucy, and Ruby has no intention of making a discreet exit from town, so she sits herself down in the first row at the church with the Doctor next to her. Drinks at the saloon are on the house all day, paid for by Kimbrough, and it all looks like it's going well until Bart eases in at the back and decides to make himself heard when the Reverend (Richard Deacon) asks if "anyone has any objections."

He mentions a woman named Mary and tells Lucy that he's probably doing her a favour as Kimbrough won't be alive by the end of the day. It's a bold move, but Bart's follow up is less smooth: he and Sam evade Kimbrough's gunmen long enough to hole up in a livery stable, where Spanish (H.M. Wynant), Swede's deputy, tries to bust in but gets a bale hook in the arm from Sam for his trouble.

The Doctor forces his way into the stable to tend to Spanish and ask what Bart is trying to prove. He's not the only visitor during the siege; as the morning turns to afternoon Bart and Sam get visits from Mr. Summerton, who offers them money to leave town, and his daughter, who wants to know why he's so intent on ruining her wedding.

It transpires that Mary was Bart's wife, and while he was away fighting in the Civil War she had an affair with Kimbrough, who discarded her as casually as Ruby, though Bart's wife wasn't as resilient and killed herself in shame. In his mind this is ample justification to pursue a vendetta at any cost, even if it's left him surrounded in a strange town.

Decision at Sundown has been described as a "reverse High Noon", and Scott's Bart has been compared to Jimmy Stewart's performances in Anthony Mann westerns like Winchester '73, The Naked Spur and Bend of the River. It's certainly among the darkest roles Scott ever took, and if it works at all it's because nobody can believe Scott's Bart could be so deranged by his grief.

Lucy tells Bart bluntly that it doesn't sound like he lost much when he lost her, and he throws her out of the stable in a rage. Witnessing this, Sam says that he can't let this happen without him knowing that he didn't think much of Mary either, for which Bart sucker punches his best friend.

Even Kimbrough, the obvious villain of the story, beings looking sympathetic in the light of Bart's suicidal rage. "Why does this man want to kill you?" he's asked.

"Maybe because he doesn't understand women the way I do," Kimbrough replies. The line might have been meant for a dark laugh, but it confirms what preceding events have hinted – that Kimbrough's power comes from his ambition and an understanding of human behaviour that Bart apparently lacks.

Sam, probably as eager to get away from Bart for a while as he's desperate for a hot meal, takes up Summerton's offer of a truce and negotiates his way out of the stable and across the road to the town's "eating place." He enjoys a bowl of stew and flirts with the Irish waitress but when he tries to walk back to the stable after throwing down his gun belt he's shot in the back by Spanish.

While Bart is under siege by Kimbrough, the townspeople have been watching it all, and have their conscience pricked by the Doctor. They regret how easily they gave in to Kimbrough's takeover, and rediscover their courage (in a series of rather stiff little set piece speeches about what good men need to do) just in time for the showdown between Swede and Bart.

Chase and his men disarm Kimbrough's gang to make it a fair duel. Swede is a bully, we're constantly told, and Bart faces him by claiming that he'll be dead before his gun is out – a credible threat, as this is Randolph Scott. It turns out to be true, and Kimbrough's sheriff bites the dust, but Bart injures his hand on a piece of metal sticking out of a wagon wheel – an awkward bit of staging that only makes sense in raising the stakes for any subsequent gunplay.

Shoddy details like this are what makes Decision at Sundown look too much like television westerns, with their recycle stock footage and clockwork plot beats, produced hastily to a rigorous bottom line. Unlike so many of the Ranown westerns, which showcased budding talent on their way to interesting careers (Lee Marvin, Richard Boone, Henry Silva, James Coburn, Lee Van Cleef), the cast surrounding Scott is as capable and unremarkable as any weekly TV episode.

Carroll is the exception, and he does a lot to make Kimbrough seem more complex and even sympathetic than a stock black hat. Robert Nott in The Films of Randolph Scott says that Carroll is "surprisingly good as a low-key town boss who seem disgusted and bemused, rather than angry or betrayed, when the townspeople turn on him."

By the time Kimbrough resigns himself to the inevitable and straps on his guns he knows that even if he walks away from the showdown his time in Sundown is over. Bart and his nemesis face each other in the dusty main street, but before they can draw Ruby shoots Kimbrough in the shoulder, telling Bart that he had no reason to try and kill the man who he claims wronged him because "You never had a wife."

Saving the town is the happy ending of many westerns, but in Boetticher's film it was never the hero's intention, and merely an accident that cost the lives of Sam, Swede and Spanish. Lucy and her father have been freed from the consequences of decisions they made out of fear and greed, and the Doctor, we presume, gets his town and a chance at his girl back. Even Kimbrough gets to ride away from Sundown in his smart little landau with Ruby on his good arm, his dignity intact.

While all this happens, though, Bart is in the saloon drowning his grief and thwarted vengeance in whisky. "His final moments, drunk and disillusioned at the bar, are handled with a sense of understated, bitter resignation," Nott writes.

"When he rides out of town for the final frame, leading his dead partner's horse behind him, you get the sense that he's planning to take his own life once he gets outside the town limits." Scott looks for all the world like Jason Robards in Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West, riding away from Claudia Cardinale slumped on his horse, collapsing to the ground dead once he's out of sight – his purpose in life and the film over.

Boetticher judged Decision at Sundown his least favorite of the Ranown films, and one of his most mediocre pictures, done out of an obligation to Scott and producer Harry Joe Brown. "It was already written, it was an old Randolph Scott picture," he said. "And I didn't like that he was drunk in a lot of the last scenes. That didn't befit him at all."

It did, however, show us a glimpse of the range that the famously stoic Scott had hidden. He could be desperate or angry in any film, but Bart Allison radiates a dark energy, a potential for chaos, that makes him almost an antihero. And like the best westerns of the '50s, Boetticher's film is a teasing glimpse of the troubling, nihilistic future of the genre, only a few years away.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.