Even when they were running little more than wire service copy, rewriting press releases and filling whole supplements with advertorial, newspapers were still haunted by the ghost of Alan J. Pakula's 1976 movie version of the bestselling book All The President's Men. I remember being called back to work at my last employer's office, far out in the suburbs, when our publisher told our new editor that he wanted to see everyone at their desks, to recreate the kind of newsroom he'd seen in Pakula's picture, itself a near-perfect Hollywood soundstage replica of the one at the Washington Post, complete with wastepaper baskets full of rubbish collected from the Post.

Never mind the abiding spectre of Richard Nixon, who will haunt Baby Boomers as long as they can recognize the names on a ballot; the ghosts of Woodward and Bernstein have lingered over journalism for as long as I can remember, replacing earlier idols like Walter Cronkite, Edward R. Murrow and H.L. Mencken. How much this had to do with being portrayed by Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman in Pakula's film is up for debate, but no one can deny that it certainly helped.

Perhaps this was what kept newspaper journalism oblivious to all the traps that lay in wait for it, some of them in plain sight. A pair of low-status city desk reporters once took down a sitting president – or at least that was the story they repeated over and over. What more proof did you need of the power of the press? Even while viewership leached away to cable news and ad dollars left for the internet, that shining moment, taught in journalism schools and invoked with every year's crop of Pulitzers, provided an endless, flattering distraction.

That power is announced with the first shots of the film – an extreme closeup of a sheet of paper in a typewriter as the keybars hammer out a date, every stroke hitting home like a gunshot. The date is June 17, 1972, when a group of men break into the Democratic National Committee office in the Watergate Building and get caught by a security guard and arrested by a group of plainclothes police.

Bob Woodward (Redford), a junior reporter on the staff of the Washington Post is assigned to the story; he overhears one of the men, James McCord, admit that he is a former CIA officer. Everything about the break-in looks suspicious, from the high-priced lawyers sent to the burglars' arraignment to the expensive equipment and the wads of cash they were carrying. He convinces Harry Rosenfeld (Jack Warden), his boss, that it needs to be looked into, and Rosenfeld persuades his boss, Howard Simons (Martin Balsam) to keep him on the assignment.

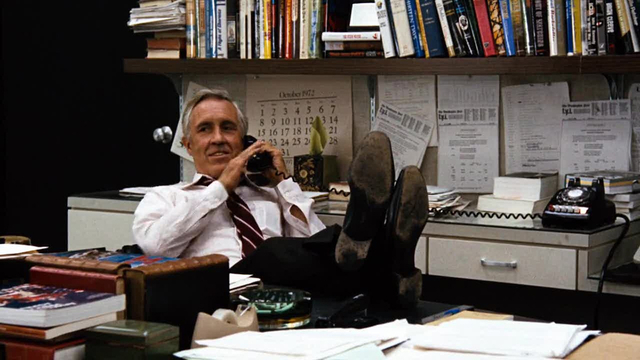

Another Post city reporter, Carl Bernstein (Hoffman) attaches himself to the story, and when the two men make a tentative link between McCord and E. Howard Hunt, who works for Charles Colson in the Nixon White House, they begin a battle to keep their story relevant to not just Rosenfeld and Simon but the Post's managing editor, Ben Bradlee (Jason Robards). The problem is that no one is willing to go on the record as they get closer to the White House, and every unattributed allegation they make is denied by the administration.

Recapping Watergate feels ridiculous, but there are at least two generations who didn't grow up with its details recycled endlessly on TV and in newspapers. And it's worth remembering that if Woodward and Bernstein had never advanced their story past this point, none of us would know what Watergate means today.

I'd go a step further and suggest that Watergate might have subsided into a journalism school study unit and a medium difficulty political trivia answer if Robert Redford hadn't become an avid reader of Woodward and Bernstein's coverage and reached out to Woodward to suggest making a film – not about the burglary or the cover-up or Nixon's downfall, but about the two reporters whose names were synonymous with it all.

Redford, whose star status was impeccable after pictures like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Sting and The Way We Were, had become interested in producing and he saw promise in the two young reporters as an odd couple, brought together by a mission whose outcome they couldn't have anticipated when they were teamed up against their wishes.

But by the time he approached Woodward the two reporters knew they had to produce a book about Watergate, and that by the time it was finally written and published it would probably have to compete with another half dozen books that would be on the shelves by the time they finished theirs. Writing a first-person narrative and not just a recap of all their published stories would make that book stand out, even if it violated an informal but venerable journalistic edict about not making the story about yourself.

And Redford's involvement, early in the creation of the Woodward and Bernstein legend, makes All the President's Men a kind of chicken and egg question about which came first – the book or the movie. Even though the latter wouldn't happen for another two years, you can argue that without it the former wouldn't exist.

It has to be understood that we wouldn't know about the Watergate break-in and its subsequent coverup today if Bradlee and his editorial team at the Post had been governed by conventional journalistic wisdom. In Woodward and Bernstein: Life in the Shadow of Watergate, Alicia C. Shepard describes how William Greider, a respected senior writer at the paper, congratulated the two young reporters on their scoop about Donald Segretti, a lawyer who worked the dirty tricks or "ratfucking" campaign against the Democrats for the Committee to Re-elect the President:

"I said Segretti was good. But that goes on in every campaign," Greider told (David) Halberstam. "But they just looked at me. I was saying that I would not have gone after that with the same set of facts. They were very polite. Then they said, 'Just don't tell us that because it happens all the time, it isn't wrong.'"

Woodward had been at the Post for less than a year, an inexperienced reporter whose writing skills were, he would admit, spotty. Bernstein was a veteran by comparison, with more than a decade of experience, but his bouts of irresponsibility and grating attitude put him on a constantly probationary status; in the film Simons asks Rosenfeld why he hasn't fired him yet.

They were city beat reporters; Woodward's biggest accomplishment was getting restaurants shut down for health code violations. Their status at the paper was lower than writers assigned to the White House press corps – older men who had earned a rather cushy post with a regular schedule, reporting whatever the White House press officer put on their plate that day. As James McCartney, a veteran Washington reporter for Knight Ridder said in Shepard's book, "The real secret to Watergate was that it wasn't done by reporters who called Kissinger 'Henry'."

Woodward and Bernstein didn't have the Watergate story entirely to themselves. They were competing with the New York Times, the Post's partner in publishing the Pentagon Papers in 1971, and were scooped by them several times, and the Los Angeles Times put three reporters from their Washington bureau on Watergate, but the paper's newsroom on the other side of the country didn't have much enthusiasm for the story. "To them," Shepard writes, "it seemed like typical political hanky-panky."

It didn't help that every new break in the Watergate story was met by scornful denials from Ron Ziegler at the White House press office, at a time when official denial was treated respectfully. In Pakula's film we see how hard it is for Woodward and Bernstein to substantiate any of their claims with a paper trail or a source willing to go on the record; by the time the story attracts the undivided attention of Bradlee he tells them they have no story and has it buried ten pages into the front section.

There is a very boring film waiting to get out in All the President's Men, but Pakula is too good a director to lapse into the usual montage of phone calling and combing through files and door knocking and typewriting, though these were nearly the whole of a reporter's working day in the pre-digital era. He overcomes this convention with shots like the one of the reporters in the round reading room of the Library of Congress, combing through piles of request slips from the White House, desperate for actual physical evidence, as the camera pulls higher and higher, hinting at their isolation and the futility of their work.

(Today, a newspaper movie would have to show a young reporter in a half-empty newsroom after the latest round of layoffs combing through social media for quotes and leads on a story, as that's often the meat of a typical online article, published hourly to keep a paper's presence alive when paper editions are vestigial, if they're printed at all.)

This is when Woodward reaches for a lifeline and calls his secret source, an official deep in the administration – the mysterious character who would be known as "Deep Throat". He makes a call from a payphone by the Old Executive Office Building (once the State, War and Navy Building, now the Eisenhower Executive Office Building) right next to the White House.

His source tells him he can't talk about Watergate and not to call him again, but Woodward finds a note tucked into a copy of the Post delivered to his home, telling him how to make a rendezvous – a cloak and dagger system involving a red flag in a flowerpot, switching cabs and parking lots at two in the morning.

Deep Throat will be Woodward's ultimate unnamed source, a source so secret that he will never be mentioned in the articles, won't answer direct questions about the story, and whose identity will be kept from even Bradlee. Woodward would keep his promise to Mark Felt, a very senior FBI official, until near the end of Felt's life, when his family chose to share the secret in a 2005 story in Vanity Fair.

Hal Holbrook plays Deep Throat entirely in the shadows, his presence announced by the flash of his cigarette lighter deep in some corner of the parking garage. His entry into the story changes the tone entirely, and what was until then a record of shoe leather reporting turns into a tale of espionage in a city full of covert operators, their presence felt but never seen. This is why Pakula's film is considered the third and best entry in his "paranoia trilogy" that began with the neo-noir Klute (1971) and the conspiracy thriller The Parallax View (1974).

Woodward's source tells him to "follow the money" – a huge and apparently untraceable slush fund used by the Committee to Re-elect the President to pay for Segretti's dirty tricks and break-ins like the one at Watergate. "Forget the myths that the media have created about the White House," he tells Woodward. "The truth is these aren't very bright guys. Things got out of hand."

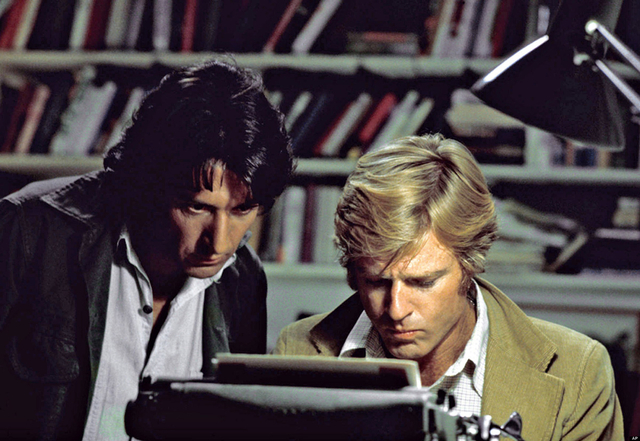

Redford and Hoffman took their research for the film seriously, spending time with the men they were portraying and hanging out in the Post's newsroom. Hoffman had actually been urged by his brother, who worked in Washington, to look into the Watergate story and looked into buying movie rights until he found out that Redford had beat him to it. He made himself a fixture at the Post, sitting on the floor during editorial meetings and even going out with Bradlee to watch an attempted suicide down the street from the office. He even said that he didn't want to leave.

Redford tried to spend the same amount of time in the Post newsroom but his presence was considered too distracting. One note that Woodward and Bernstein sent to scriptwriter William Goldman was that "there should be women in this movie. They were in our lives, will be and should be."

Goldman's first draft didn't go over well with the reporters of the Post newsroom. Bernstein went so far as to write a second draft with his new girlfriend, journalist Nora Ephron; it's considered to be her first screenplay in a career that would include Silkwood, When Harry Met Sally, Sleepless in Seattle and You've Got Mail. Goldman was furious, and ten weeks of preproduction were lost smoothing it over. Later, in a 1983 book he wrote about his Hollywood career, Goldman wrote that he wouldn't change a thing in the scripts he wrote but that if he had the chance "I wouldn't have come near All the President's Men."

But Goldman did deliver on Woodward and Bernstein's advice about women in the story, and there are several key scenes where the reporters, alone or together, seek the information they desperately need from among the throngs of women who staff the bureaucracy that keeps Washington functioning.

They even put pressure on women in their newsroom, like a young reporter who once dated someone at C.R.P., and Sally (Penny Fuller), who was involved with Ken Clawson, a White House staffer and former Post reporter involved in the dirty tricks campaign. (Sally is based on Marilyn Berger, who would later marry 60 Minutes creator Don Hewitt. Strangely, Post publisher Katharine Graham is mentioned but never seen in Pakula's movie; she would have to wait until Meryl Streep played her in The Post, Steven Spielberg's 2017 film about the Pentagon Papers.)

Their most crucial encounter is with "the Bookkeeper", played by Jane Alexander and based on Judith Hoback Miller, the bookkeeper for C.R.P. She initially rebuffs Woodward and Bernstein, but Bernstein is persistent and desperate and returns to her house to overcome her obvious fear, not just for her job but for consequences from those unseen operators she insists are just out of sight, watching people like her.

Pakula knew that he needed an actress who could sell both fear and an eagerness to see consequences for the men she works for. Alexander was known mostly as a theatre actress, and while she had made a big impression with her first film role in The Great White Hope (1970), picking up the first of many Oscar nominations, she had only appeared in two other films since then.

Alexander and Hoffman let us feel her reluctance and his unreasonable demand to provide information that could cost her more than just her job, after she describes being quietly but firmly threatened. The growing menace that surrounds the investigation is ultimately spelled out by Deep Throat, who describes a conspiracy that has spread all through the government, and which he says is now threatening Woodward and Bernstein.

What began as a clumsy burglary is revealed as a malignancy embedded in every level of the company town that is Washington, and when Woodward and Bernstein finally make the breakthrough that provides the story that Bradlee wanted, we see his barely hidden glee at landing a shot on the White House – revenge for being set up to look like a fool by Lyndon Johnson a decade earlier.

The movie ends as the reporters finally link the burglary at the Watergate through McCord, G. Gordon Liddy and E. Howard Hunt to White House chief of staff H.R. Haldeman and former attorney general John Mitchell. Woodward and Bernstein are seen typing away in the Post newsroom while Nixon takes the oath of office after his landslide 1972 re-election. A final montage of teletype machines smashing out the headlines on subsequent stories takes us up to the president's resignation in August of 1974.

The bet Redford took on Woodward and Bernstein's story paid off with a box office smash and eight Oscar nominations, including one for Alexander, and wins for Robards and Goldman. Bernstein would embrace the celebrity conferred by their bestselling book and hit movie, while Woodward was far less comfortable, remaining at the Post for most of his career and using his access to write books on nearly every president the paper covered, the CIA, the Supreme Court, Mark Felt and even John Belushi.

Both men admit to living with Redford and Hoffman as their doppelgangers since Pakula's movie was released, though no one believes their complaints are genuine.

Bill Murray recently did an interview with Joe Rogan where he said that he was shocked at how inaccurate Wired, Woodward's book about John Belushi, was to the man he called a close friend. "I read five pages of Wired," Murray told Rogan, "and I went 'Oh my God. They framed Nixon.'" Woodward's book, he said, bore no resemblance to the man he knew, which made him doubt everything he had until then assumed to be true about Watergate.

In The Ends of Power, H.R. Haldeman's memoir about Watergate, the former ad man, Nixon chief of staff and prison parolee alleged that the CIA ran a campaign that used Bob Bennett, E. Howard Hunt's employer and "a CIA 'asset'", to feed information implicating Chuck Colson, a special counsel to Nixon, in the break-in "and away from the CIA. Bennett was also feeding Woodward other information for which the reporter was 'suitably grateful.'"

That there was a covert war going on between the CIA and the FBI while Watergate raged is a conspiracy theory that never got enough oxygen to thrive, and a reminder that what most of us know about Watergate is mostly contained in a two-plus hour movie that was obliged to leave out quite a lot, including Barry Sussman, the city news editor at the Post and the man who assigned Woodward to cover the burglars' court appearance. Despite working closely with Woodward and Bernstein on the Watergate stories he was dropped from co-authoring their book and subsequently deleted from the Post newsroom in Pakula's movie, written out because there was one middle-aged male editor too many.

When Alicia Shepard approached Sussman for her book, he replied that "I don't have anything good to say about either one of them." As for Deep Throat, Sussman would write that his importance "as a key Watergate source for the Post is a myth, created by a movie and sustained by hype for almost 30 years...an investigator in Miami who helped us one time was a lot more important than Deep Throat."

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.