Let's just get this out of the way first: The Last Picture Show was set in small Texas town starting in 1951 and was released in 1971. That would be the same interval of time for a film made this year and set in...2005.

I think you know what I'm getting at here. This is a little temporal exercise all of us do if we've lived long enough.

2005 doesn't seem like a long time ago. And except for the interregnum forced on us by the COVID lockdowns of 2020-2022, there doesn't seem to have been such a massive shift in culture, fashion, politics and society as the one that we're sure happened in the two decades between the first episodes of I Love Lucy and All in the Family.

It's certainly hard to imagine any director today making a film set in the year YouTube was launched look and feel like the distant past – certainly not the way Peter Bogdanovich told the story of a year in the life of two high school friends in the dying oil town of Anarene, Texas.

You don't need to be a physicist to understand that time is relative, that sometimes it seems to move a lot faster, and that if nostalgia – even the bittersweet variety that suffuses The Last Picture Show – needs any single condition to survive, it's the realization that more than just years separate us from a moment in the past.

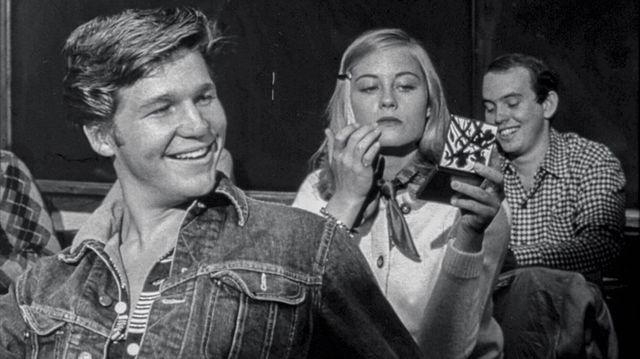

The Last Picture Show begins with a slow pan down the main street of a dusty West Texas town, until the camera settles on the local cinema – a little storefront called the Royal. The marquee tells us that Father of the Bride is on the top of that night's bill, and inside we meet our protagonists – Sonny (Timothy Bottoms) and Duane (Jeff Bridges).

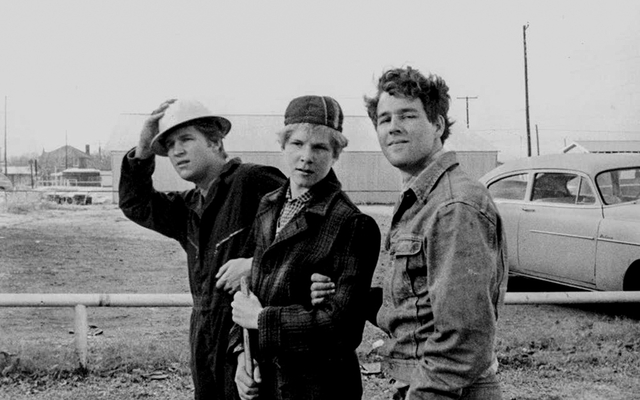

Like thousands of towns all over Texas and America, high school sports are a big deal for the adults and the likely high point of some students' lives. But Sonny and Duane will probably try to forget about their brief athletic careers as Anarene is a town on the way down and its football and basketball teams are on a losing streak – something the men in town remind the boys of constantly, with taunts about learning to tackle.

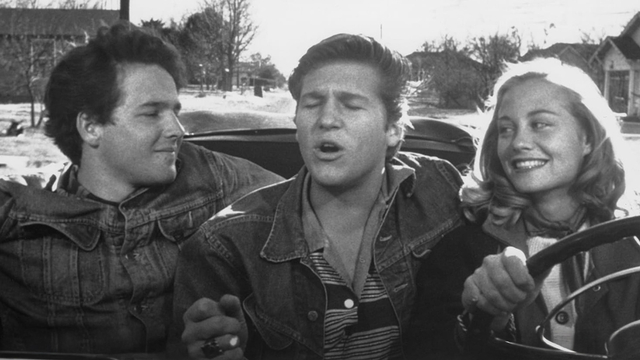

Their minds, in any case, are occupied elsewhere – mostly with running the bases with their respective girlfriends. Sensitive Sonny is going steady with the strident Charlene (Sharon Taggart) while the more confident, reckless Duane is hooked up with Jacy (Cybill Shepherd), daughter of the local wildcat oil baron and the prettiest girl in town.

The Last Picture Show was only Bottoms' second picture, and the screen debut of Shepherd, who until Bogdanovich saw her on the cover of a magazine was a successful model with little interest in a movie career. It was Bridges' fourth movie role, though he was the son of actor Lloyd Bridges and made his screen debut two decades earlier as an infant in The Company She Keeps, a flop starring Lizabeth Scott and Jane Greer.

Casting relative unknowns was one of the many wise decisions Bogdanovich made with his film; it made it easier for audiences to accept them as teenagers (Bottoms was 20 years old when the picture came out, Shepherd 21 and Bridges 22) and imagine them embodying characters who would lay the foundation of their onscreen personas in the decades of stardom that followed. Just as crucial was casting Bottoms' younger brother Sam as Billy, the mute, simple minded boy who Duane and Sonny alternately treat as their mascot, sidekick or younger brother.

Even more critical, though, was the director's choices to play the adults with whom his young leads interact in the picture. There's a trio of older women: Ellen Burstyn as Jacy's mother Lois, Eileen Brennan as Genevieve, the waitress at the town's café, and Cloris Leachman as Ruth, the lonely and neglected wife of the high school's crude, bullying (and closeted) coach.

And there's Ben Johnson as Sam the Lion, father figure to the boys, nominal patriarch of Anarene and owner of the only places to have fun in the dying town – the movie theatre, the pool hall and the café. Something has gone terribly wrong with families in Anarene: we only briefly meet Duane's mother late in the film and Sonny's single scene with his father is a brief, painfully awkward exchange at the town's Christmas dance.

(Bogdanovich said that he based this scene on an encounter he once witnessed between Jerry Lewis and one of his sons. If that sounds like name dropping get used to it – most of the director's stories were like this.)

Billy is apparently completely without family, and spends most of his time sweeping Anarene's main street with the worn stub of a broom, under the watchful eye of Sam. The older man has lived what we are meant to understand is a wild life, and instead of becoming tougher it's made him wary of the casual cruelty of young men and how small town life can be as pitiless as big cities are presumed to be.

Bogdanovich said that Johnson had no interest in playing Sam. His career had mostly been spent as a stuntman or playing small roles; he was a favorite of John Ford, appearing in Ford classics like Fort Apache, 3 Godfathers, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon and Rio Grande. Ford even cast him as the lead in Wagon Master (1950) before a decade-long rift with the director.

Bogdanovich, a serious movie fan and critic before he got his shot at directing with Targets (1968), was adamant in casting Johnson as Sam but the actor repeatedly turned him down, saying that the script had "too many words." Desperate, the young director called Ford himself, who pressured Johnson to give the young man another chance. "You put the old man on me," he complained to Bogdanovich, who promised the grizzled actor that playing Sam would win him an Oscar – or at least a nomination.

Johnson got that Oscar, along with a BAFTA, a Golden Globe and a New York Film Critics Award, and the single scene that did it was the one where he takes Sonny and Billy to a local fishing hole. In a monologue comprised of a single shot, Sam tells Sonny that he used to own the land they're sitting on, and how after his wife went mad and his sons had died he had an affair with a young married woman, a reckless beauty who challenged him to race their horses across the water. The memory, Johnson lets us know, both haunts and intoxicates Sam.

Bogdanovich was the son of eastern European immigrants, of an artist father and an intellectual mother, who spoke Serbo-Croatian before he could speak English. He had seen writer Larry McMurty's 1966 novel about his small-town Texas youth on the rack in a drug store and liked the title, but put it away after reading the description on the back, sure that the story had nothing to say to him.

A friend, the actor Sal Mineo, later gave him a copy saying that he'd wanted to star in a film version but thought he was too old. "What's Sal thinking about?" he asked his wife, production designer Polly Platt. "This thing's all about Texans. I don't know anything about these people." But they both read the book and decided to bring it to producer Bert Schneider (Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces, Drive, He Said), who wanted to make it despite Steven Friedman, an aspiring producer and lawyer at Columbia pictures, having bought the option on McMurtry's novel.

Friedman was brought aboard as coproducer and Bogdanovich set to writing a screenplay with McMurtry. They drove all across West Texas looking for locations before stopping in Archer City, just south of Wichita Falls, where McMurtry had grown up. He'd changed the name of the town to Thalia for the book, and it had been the setting for Hud (1963), which was based on McMurtry's first novel. Orson Welles told Bogdanovich that he should make the film in black and white (do you see what I mean now?) and cinematographer Robert Surtees (The Bad and the Beautiful, Oklahoma!, Raintree County, Ben-Hur, The Graduate) was signed to shoot.

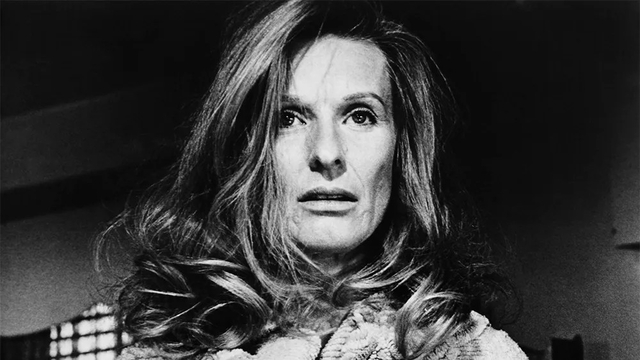

The best decision Bogdanovich made, though, was the casting of the three older women in the story. Cloris Leachman, on a break from The Mary Tyler Moore Show, plays Ruth Popper with wholly earned pathos, a woman too well-raised to leave her indifferent husband, desperate for affection. Her need draws in the sensitive Sonny despite his infatuation with Jacy.

Eileen Brennan's Genevieve feeds the boys cheeseburgers and Dr. Pepper at the café where she works to try and pay off the mounting medical bills for a husband who remains offscreen. She's trapped – in this town, in that job – but instead of being bitter she offers them wry advice between cheeseburgers. She plugged into the town's all-seeing web of gossip but offers sympathy instead of judgment, a maternal figure to match Sam's paternal one.

When we're introduced to Ellen Burstyn's Lois we're sure we have her number: a fading beauty queen cuckolding her husband with his roughneck foreman Abilene (Clu Gulager), molding her daughter in her image and setting her up for the same emotionally barren and dissatisfied future. But the script – and Burstyn – force us to observe Lois beyond our assumptions, and by the time the film is over she's revealed a reserve of empathy and some astringent wisdom that provide solace to Jacy and Sonny at the lowest points in their young lives.

There was a sobering moment when I realized that Genevieve, Lois and Ruth, the latter casually referred to by Duane as an "old woman", are probably still only in their late thirties by small town math – married young, their lives less than half over. (The actresses were all on either side of 40 when they made the film, with Leachman the oldest.) It might seem old to an 18-year-old, but I long for the energy I had in my late thirties today, and this epiphany will likely make the film play very differently if you're closer to 20 or 50.

Sadly, these women and the actresses who play them are usually cast in the shadows by Cybill Shepherd's Jacy – one of the most startling film debuts ever, mostly because no one believed this untrained cover girl could pull it off. Knowing that the performances of his young cast would make or break the movie, Bogdanovich invited the resentment of his crew by focusing all his energies on the actors and enforcing a rule that crew weren't allowed to eat or even interact with the cast.

But much of the focus he put on Shepherd was because Bogdanovich fell in love with her over the course of production. Polly Platt, the director's wife and production designer and mother to their two daughters, got to be an unwilling witness.

Writing about it in Picture Shows: The Life and Films of Peter Bogdanovich, Andrew Yule quotes Platt confiding about the affair on set, saying that her husband "has a terrific nostalgia for his teenage years in the fifties – Holden Caulfield ice-skating at Rockefeller Plaza with wholesome young girls in knee-socks – and somehow he's managed to transfer these feelings about his own adolescence to the totally different experience of the kids on the film."

Platt complained that "I end up 'doing' Cybill, her overall appearance as Jacy, to lock into Peter's longing fantasies. In reality I've created a rival for myself, I guess. Well, anything for art, huh?"

Bogdanovich cast Bridges because he thought the actor's abundant charm and charisma would imbue appeal into a character he found unlikeable in McMurtry's book. He took a similar gamble that Shepherd's hypnotizing beauty – and her director's clear infatuation with it – would do a lot to make us want to watch Jacy despite certain knowledge that she's the sort of young woman whose heedless disregard for anything but the abundant possibilities beauty brings her makes her dangerous, even monstrous.

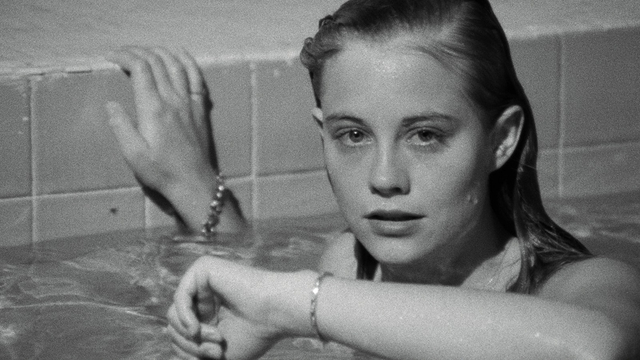

This is undercut early in the picture, in a scene that lets us feel the vulnerability of a girl like Jacy. Dissatisfied with being at the top of Anarene's social ladder, Jacy is desperate for a place in high society in Wichita Falls, and she uses Lester (Randy Quaid), a persistent suitor and rich man's son, to get invited to a pool party at the home of Bobby Sheen (Gary Brockette), an even richer man's son.

The catch is that it's a naked pool party, and initiation means undressing in front of everyone, standing on the diving board. This was the nude scene that kept Shepherd from signing on to the picture, and when Bogdanovich promised it would be filmed on a closed set she had a legal document drawn up holding him to this bargain.

The camera squarely frames Shepherd as she gets undressed, switching between an unblinking frontal shot to cutaways that show her audience as they watch her, enjoying their ability to demand this ritual humiliation as much as any prurience or lust. It does nothing to excuse Jacy's casual discarding of both Duane and Sonny in pursuit of whatever selfish needs motivate her, but it lets us see how Jacy accepts the certain knowledge that her only value is in how she looks.

Two years later Shepherd was shocked to see nudes of herself published in Playboy magazine, who had obtained a print of the film and made blow-ups from frames taken from the pool scene. Shepherd took Playboy and Hugh Hefner to court, and as part of the settlement she got the rights to Saint Jack, a Paul Theroux novel that Bogdanovich would make into a movie starring Ben Gazzara in 1979, around the time her relationship with the director came to an end.

(This wouldn't be the last time Bogdanovich would deal with Hefner or Playboy, though the story of Dorothy Stratten, They All Laughed, Bob Fosse and Star 80 will have to wait for another column.)

When The Last Picture Show was released it was both decried and applauded for its frank picture of young lust, sex and infidelity in small town America. McMurtry could certainly tell that story based on his own memories of Archer City, but Bogdanovich's decision to show the flaming youth of West Texas in the era of Hank Williams with such post-Code sexual frankness is proof of my adage that despite the costumes and setting every film is really about the time when it's made.

The Last Picture Show might be full of saddle shoes and greasy ducktails and cars before the rise of tailfins but it was made in the smoking aftermath of the sexual revolution's biggest battles, meant to appeal to the young "beneficiaries" of that moral rebellion as much as the middle-aged who were actually young before battle was joined.

It's the only way the film undercuts how Bogdanovich, Platt and Surtees did such an incredible job evoking a single year from the autumn of 1951 to the autumn of 1952. You can feel the hot wind on Anarene's main street and taste the dust in your mouth; among its many accomplishments is the way the film strives for historical accuracy in every detail, with the certainty that the texture of life twenty years earlier was palpably different while inferring that we were still transfixed by sex and longing to get naked.

The Last Picture Show launched its director and his cast into great careers, netting eight Oscar nominations and two deserved wins for Johnson and Leachman in best supporting roles. It certainly wrote a golden ticket for Bogdanovich in Hollywood, though the diminishing quality of his filmography (At Long Last Love, Illegally Yours, To Sir with Love II, The Cat's Meow, She's Funny That Way) managed to make The Last Picture Show one of those Greatest Films of All Time That I Only Bothered to See This Week.

The film ends how it begins, with that long pan down Anarene's main drag, resting on the now-shuttered Royal, its marquee blank. The Royal on East Main Street in Archer City, TX was a burned-out shell when the film was shot and was still empty when Bogdanovich returned in 1989 to make Texasville, a sequel to The Last Picture Show.

The less said about the sequel the better; it flopped resoundingly, perhaps because the trailer gave fans of the original film the impression that Texasville was a broad, garish '80s comedy and not a stark coming of age story. The best thing that came out of it was George Hickenlooper's Picture This, a documentary about the making of the film, and the production arrived just in time to shore up the ruins of the Royal for another decade.

Archer City seems to be doing much better today. The Royal was reopened as a music venue and event space, though the town's revival began when McMurtry opened a branch of Booked Up, his rare book chain, around the corner from the Royal. The Texaco station might be gone but Archer City has a boutique hotel next door and a literary centre dedicated to McMurtry in his old bookstore. Nobody would make a film about a dying Texas town in Archer City today.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.