Frank Sinatra was emerging from the infamous dark period of his career in 1954, buoyed by his performance in From Here to Eternity and the Oscar he won for best supporting actor. Long gone was "Swoonatra" and the bobby-soxer legions outside the Paramount Theater on Times Square a decade previous. Also gone was Ava Gardner, now with matador Luis Miguel Dominguin, though their divorce wouldn't be finalized for three more years.

It was a leaner, meaner Sinatra that rebounded from what was considered a fatal career slump, and he followed up Maggio in From Here to Eternity by playing a psychopath trying to assassinate the American president in Suddenly, an economical, noir-inflected picture where he made no less than Sterling Hayden the good guy. That might have been a bit too dark, so he corrected course – slightly – by signing on to star opposite Doris Day, another former band singer, though one whose career had been on a steady rise since she went Hollywood.

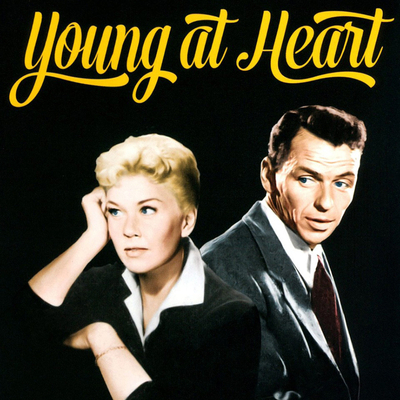

Day herself was at a career crossroads, near the end of her hated contract with Warner Bros. and itching to prove herself as an actress. It was a significant moment for these two American icons to meet – their only appearance together apart from an episode of the radio show Your Hit Parade in 1947 – and reactions to it in the long decades since have always seemed coloured by disappointment that it wasn't more momentous.

Sinatra was also at the beginning of what is considered the zenith of his recording career, free of Columbia Records and their musical director, Mitch Miller. His new contract with L.A.-based Capitol looked like a bad deal from the outside: he only got a thousand bucks up front, was tied to the label for seven years, and had to pay his own studio expenses. A real loser of a deal.

His signing was not met with enthusiasm by Capitol staff when it was announced at a company convention. Label vice president Alan Livingston, quoted in Sinatra: The Life by Anthony Summers and Robbyn Swan, recalled that "there must have been a couple of hundred guys there, and the whole room went 'Unnhhoooo....' The whole staff was so totally underwhelmed that they groaned en masse."

But Capitol teamed Sinatra up with Nelson Riddle, one of their staff arrangers, and their collaboration would produce some of the singer's greatest recordings, the first results of which would be featured in Young at Heart, the film Day and Sinatra made on a backlot set at Warner's Burbank studio – a stylized suburb so contrived that it would make a Douglas Sirk film look like kitchen sink realism.

We hear Frank sing the title song over an establishing shot of that idealized American street, where white picket fences delineate the front yards of archetypical suburban homes as they looked before the Levittown blueprint spread across the country. The credits roll, and alert eyes will note that Doris has top billing over Frank; that would rarely happen again.

Sinatra was the first singer to record the tune, written by Johnny Richards with lyrics by Carolyn Leigh. Riddle arranged and conducted the record, which was cut in December of 1953 and released a month later, becoming such a huge hit – Frank's first in years – that it moved Warners to make it the title of the film.

It has, to be sure, almost no lyrical resonance with the film that follows. But in 1954 a studio like Warners was still putting together films the way they always had – as a package of parts assembled from what they owned, borrowed or recycled. The story itself was a remake of Four Daughters, a 1937 Warners picture, directed by Michael Curtiz and starring John Garfield, Claude Rains and the three Lane sisters – Priscilla, Rosemary and Lola – in a bit of stunt casting augmented by Gale Page as the fourth daughter.

In Young at Heart the four daughters are reduced to three sisters: Laurie (Day), Fran (Dorothy Malone) and Amy Tuttle (Elisabeth Fraser). They're the daughters of a widowed professor of music (Robert Keith), living in an impeachably Yankee Connecticut town with their spinster Aunt Jessie (Ethel Barrymore).

Life is conducted around the grand piano in the parlour where the girls, all musical prodigies, form a quartet with their father. Jessie, who apparently skipped the family's musical gene, entertains herself watching prize fights on the television. Fran is going steady with Bob (Alan Hale, Jr.), the oafish but likeable son of a local property developer, while Laurie and Amy console themselves by vowing to have a double wedding when their matrimonial ship sails into harbour.

What looks like that boat arrives in the form of Alex (Gig Young), a promising young composer whose father was a friend of Prof. Tuttle. He shows up just in time to deliver a litter of puppies for the neighbour's dog, gift the runt of the litter to Laurie and head off to talk her father into offering him not only a job at the local conservatory but a dinner invitation that night. He brazens his way into the family, arranging their places at the dinner table and charming all three sisters, though his affections are focused on Laurie.

Flash forward and Alex is very nearly a member of the family; a day at the beach reveals that he and Laurie are an item, though he's distracting Fran from Bob while Amy is carrying a serious torch for him. They look like a perfect couple, a high-spirited temperamental match, though Alex can be more than a bit overweening, as Aunt Jessie and Prof. Tuttle note early and often.

The beach scene is also a reminder of what got forgotten later in Day's career, when her image hardened around a pop culture attitude that imagined her as cold and uptight, the virtual virgin who was, notwithstanding, a top box office draw. Sporting just a sweater and a tiny pair of shorts she was, in the words of Sinatra biographer James Kaplan in Sinatra: The Chairman, "a full-fledged sex goddess, whose long legs and curvaceous figure, freckles and turned-up nose and thousand-watt smile, had stirred the loins of a million men," such as the writer John Updike, "who would obsess over her in poetry and prose for the rest of his life."

Kaplan, like so many biographers of Sinatra, goes so far as to ape the sort of language it's presumed the Chairman himself would use, describing Day as "the stealth counterpart to Marilyn Monroe: her all-American features, bobbed blonde hair, and sunny forthrightness made look like a farm girl but hinted at an excellent roll in the hay."

But into every sunny day some rain must fall, and that dark cloud arrives in the form of Barney Sloan (Sinatra), a pianist pal of Alex, hired to do arrangements for the Broadway show he's writing and to, as Prof. Tuttle acidly jokes, cover up all the things Alex has stolen. He shows up on their porch, verbally spars with Aunt Jessie and presents himself as a challenge to Laurie, who can't believe anyone can exist in such a permanent bad mood.

Barney is a Nietzschean anti-hero in a Dale Carnegie world, and he comes into the Tuttles' lives with a hard luck story. An orphan, he'd finally landed a decent job when war broke out; hoping to become a hero or die trying, he ended up with just enough of a wound to send him home. Since then he's been struggling, relying on handouts from friends like Alex who, we're meant to understand, have cornered the market on luck while all he's got is talent.

He's convinced that the fates have it in for him, taking more away from him with every little bit he can earn, though the way his eyes look upward whenever he talks about his tormentors and this raw deal, it's hard not to conclude that Barney's beef is with God Himself. He nonetheless finds a place in the family's orbit, punching up Alex's tunes and playing in the town's designated smoky joint to the usual audience of distracted drunks.

Young at Heart was directed by Gordon Douglas, who Kaplan describes as "an amiable hack". He got his start in the business with Hal Roach, and ended up directing a series of Our Gang shorts, along with Zenobia (1939) – a team up of Oliver Hardy with Harry Langdon while Stan Laurel was in a contract dispute with Roach – and Saps at Sea, the last Laurel and Hardy feature made for Roach.

He moved on to RKO, Columbia and then Warners, where he made films like I Was a Communist for the FBI (1951) and, the same year as Young at Heart, the giant ant sci-fi monster flick Them! He was by no means a director of note, but he was good enough for Sinatra, who would work with Douglas again on Robin and the 7 Hoods (1964), Tony Rome (1967), The Detective and Lady in Cement (both 1968).

What he did for Sinatra in Young at Heart was present him as the quintessential saloon singer, hunched at the upright in dives like the Hole in the Wall playing torch songs to indifferent crowds, working on his own songs after closing time (his hands on the keys provided by longtime accompanist Bill Miller) amidst the chairs piled on tables while waiters bring him coffee.

There are no production numbers in Douglas' film, but it's definitely a musical, with strings easing their way into the soundtrack while Doris and Frank sit down and sing, on the beach, in the parlour or the saloon. And there's no denying that Sinatra's numbers are the highlights of the picture.

Besides the theme song, Frank provides his versions of three standards that would help define him as a singer for the rest of his career: George Gershwin's "Someone to Watch Over Me", Cole Porter's "Just One of Those Things," and most of all Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer's "One For My Baby (And One More For The Road)". Along with five of Day's numbers, they would be released on a 10" LP by Columbia – Day's label, not Frank's – to promote the film.

"One For My Baby" wouldn't appear on an actual Sinatra record until 1958 and Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely, one of the LPs that are considered part of his Capitol cycle of so-called "suicide albums" alongside In the Wee Small Hours (1955), Where Are You? (1957) and No One Cares (1959). They're the musical foundation of the Sinatra who would close his concerts sitting at the piano with Miller, drink in one hand, cigarette in the other – the rueful man, forged in heartbreak after Ava Gardner, telling us how he survived, but only just.

Writing about the song, Sinatra and Miller nearly ten years ago, Mark described it as "a marvelous thing that works at so many levels: it evokes the tinny sound of a saloon piano, and it meanders a little woozily, like a fellow who's drunk a skinful heading back to the bar for one more, and it also has a kind of bleak, weary acceptance about it, as if both storyteller and barman know that in the end the one buttonholing the other will change nothing."

Day is in fine voice but her material is far less memorable than Sinatra's: "Hold Me in Your Arms", "There's A Rising Moon", "Till My Love Comes to Me", "You My Love" and "Ready, Willing and Able". Only the latter seemed to distinguish itself, charting in the UK. James Kaplan speculates that Day's songs were chosen by her husband Marty Melcher because he had a cut of the publishing rights – the singer had Jack Warner ban Melcher from the set when he tried to pitch him material.

Writing about the film in his biography, Considering Doris Day, Tom Santopietro contrasts the two stars, whose personas were so different that it made their onscreen romance seem improbable:

"In the context of Young at Heart, it's obvious that Laurie/Doris comes alive in the morning sunshine, while Barney/Frank does so at night in a smoky bar. Why these two were ever attracted to each other remains a total mystery even at the end of the film, and as the camera pulls back during the final shot of an unnaturally clean suburban street, Sinatra singing the title song, one can only think, 'Those two won't last one week together – especially with that damn harp in the living room.'"

Like Santopietro, I have a hard time imagining Laurie and Barney being attracted to each other, never mind running off to elope while she leaves Alex waiting at the altar. She "wouldn't give him the time of day. Similarly, he would be turned off by her relentless optimism."

But they end up together, he speculates, because they embodied defining facets of the decade: "In many ways Day and Sinatra represent the optimistic and dark sides of post-war 1950s America; both worldviews held genuine appeal, both had adherents, and they never really mixed until the social upheaval of the 1960s."

Frank's woebegone Barney, he says, is the only plot motivator in the picture, the catalyst that creates drama in what, until he shows up on the Tuttles' doorstep, looked to be a pretty cloying story. But the film still doesn't work "for the simple reason that there is not one shred of rapport between the two. So different are their styles that at times it seems as if there is a line bisecting the screen, with each star's footage having been filmed separately and then pasted onto the screen."

By the film's final act Alex is driven to the train station by Barney to exit the story, a Broadway success who doesn't end up with any of the Tuttle sisters, forcing cash on his luckless friend. (It's a role – the gracious loser – that Young would reprise a few years later with Day and Clark Gable in the far superior Teacher's Pet.)

Still convinced he's unworthy of Laurie and her family, stuck on self-loathing and shamed by his friend's generosity despite Alex's slip out of the Tuttle familial embrace, Sinatra's Barney succumbs to his depression. Driving Bob's car through the dark as rain turns to sleet, he decides that everyone would be better off if he wasn't around, so he turns off the windshield wipers and steps on the gas, his eyes turning upward as the snow turns the windshield white.

Sinatra was never confident of himself as an actor, and he was back to his old habits when filming Young at Heart, irritating Day by turning up hours late to set and insisting on doing as few takes as possible. But he nails this wordless scene, channeling his insecurity and self-loathing into Barney, in what would have been a downer climax if the film had stuck to the original story of Four Daughters.

But nobody – not Sinatra, not Warner Bros. – wanted to end the film with Barney's suicide, so we get that final scene with the "unnaturally clean suburban street" and Sinatra's reprise of the title song while Barney finally finishes the song he's been working on since he met Laurie. It's wildly unsatisfying, but the film has nonetheless accomplished its unintended goal: filling out that shadowy part of the Sinatra persona that would let him end his shows with "One For My Baby" for the rest of his career, turning every concert hall, arena and Vegas showroom into that tawdry bar at closing time.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.