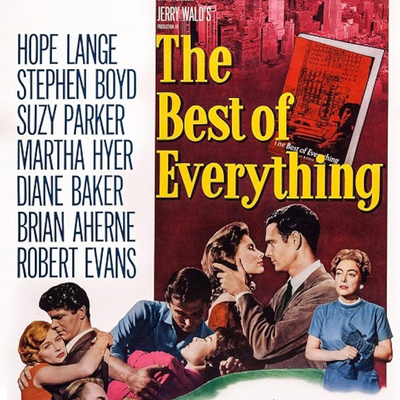

The Seagram Building on Park Avenue in midtown New York City had only just finished construction when it became the setting for The Best of Everything, a melodrama about working women in the big city, directed by Jean Negulesco for 20th Century Fox. Our heroine Caroline Bender (Hope Lange) emerges from the subway, early for her first day of work, and gazes up at Mies van der Rohe's brand new modernist skyscraper from the marble plaza at its base.

Writing about the building in the New Yorker just after its completion – but before it was awarded its occupancy permit from the city – Lewis Mumford wrote that it "emerged like a Rolls-Royce accompanied by a motorcycle escort that gives it space and speed." He finds a few faults in it: there's nowhere to sit in the vast plaza separating the front doors from the street; the beech trees planted on either side of the tower "seem closer to the spirit of Salvador Dali"; the granite slabs in the square's pools look badly finished, with smudges of cement between the cracks and inelegant, utilitarian plumbing.

Most of all, though, Mumford criticized it for being "a building that exhausts every resource of art and engineering to create an imposing visible effect out of all proportion to its human significance." It's an error that he thinks echoes "our whole civilization, which now sacrifices on the altar of the bureaucratic functions and engineering services what it once gave, in awe and exaltation, only to divinities."

Le Corbusier, the wildly influential Swiss-French architect and peer of Mies, once called houses "machines for living in." By extension modernist skyscrapers like the Seagram Building were machines for working in, and as the credits roll on The Best of Everything we see the workers arrive, a river of women, mostly young, flowing out of the subway entrances on to the streets and into the city's skyscrapers.

They are, thankfully, still recognizably human at the mid-century mark. After Caroline takes in the desks and offices of Fabian Publishing, her prospective new employer, they emerge from the elevator bank and burst through the plate glass reception doors. Some women are still in curlers, which they shed in bathrooms while tugging at foundation garments; others change into their work shoes, kept in the bottom drawers of their desks.

Caroline is at Fabian answering an advertisement in the paper. "SECRETARIES," it reads: "You Deserve the Best of Everything," going on to itemize all those things: "The Best Job – The Best Surroundings – The Best Pay – The Best Contacts!!" This was based on an actual ad author Rona Jaffe read in the New York Times, and before the book it inspired was even published it had been optioned by Jerry Wald at Fox, who saw it as a showcase for the roster of young actors under contract to the studio.

Lange's Caroline is a newly minted Radcliffe graduate, still living at home with her parents in Connecticut in what a single brief scene hints is ample middle-class comfort. (If Jaffe were writing the book today she'd probably be employed as an unpaid intern thanks to some family connection, part of the accredited and subsidized underclass of hopefuls that keep publishers and other old media entities alive.)

I remember Rona Jaffe for her frequent appearances on '70s television, where she was called upon for her expertise on celebrity, the movie industry, sex and scandal. Somehow I completely missed that she was an author, though her work – once derided as trash by literary critics despite (or perhaps because of) how well it sold – has been undergoing a reappraisal in recent years, as the ancestor to shows like Sex and the City and creative inspiration for Mad Men.

(Jon Hamm's Don Draper is reading Jaffe's book in a season one episode of Mad Men; his wife Betsy comments that it's much better than the movie, and that she was distracted by Joan Crawford's eyebrows.)

But when her first novel was published she was taken very seriously, staking out the "women explaining women" beat ahead of writers like Helen Gurley Brown (who hired Jaffe at Cosmopolitan) and Betty Friedan. Jaffe was also a Radcliffe grad who took a job working for Fawcett, the mass-market paperback publisher (like Dell and Ballantine) who provided the model for Derby Books, one of the imprints owned by Fabian.

After effortlessly passing a typing test administered by Mary Agnes (Sue Carson), the office gossip and queen of the secretarial pool, Caroline is told to take over the desk of Gregg (Suzy Parker), who hasn't shown up for work that morning. She quickly meets April (Diane Baker), another new hire, referred to Fabian by her roommate, Gregg. The three women become the centre of the story after Caroline moves from Connecticut to share Gregg and April's realistically cramped West Village apartment.

Caroline – and Gregg, when she isn't playing hooky from the office to audition for parts in plays or commercials – becomes secretary to Amanda Farrow (Crawford), editor of Derby and scourge of the secretarial pool. Amanda is a career woman, harsh and demanding (Meryl Streep would reprise her as the Anna Wintour proxy in The Devil Wears Prada); she'd be Caroline's role model if she weren't such a jet-powered bitch, and if she didn't openly mock the younger woman's motivations based on her own experience.

Crawford hadn't worked in two years when she took the role of Amanda ten days before shooting started, her first supporting role since silent films. She needed money after the death of her fourth husband, Alfred Steele, CEO of Pepsi-Cola. She had just been elected to the board of the company and convinced Wald to have a Pepsi machine put in the breakroom set of Fabian's offices. Her role was edited down considerably, and Diane Baker said later that cut footage included an incredible drunk scene.

Amanda aside, the main antagonists in the three women's lives are the men they attract. For Gregg it's David (Louis Jourdan), a successful theatre director and serial lothario; for April it's Dexter (Robert Evans), a rich playboy she meets at a company picnic. Caroline starts the movie with Eddie (Brett Halsey), her fiancé, who goes to England for a year on a scholarship and marries an oilman's daughter while he's there.

Hovering on her periphery, though, is Mike (Stephen Boyd), editor of Fabian's teen magazine. We first meet him on the morning of Caroline's first day, hungover and stumbling with a simian lope through the secretarial pool to his office. He spies Caroline and wanders over to get a closer look before retreating to his office. It doesn't seem an auspicious start, but none of the three women are allowed to make good choices in men in Jaffe's story.

In the original novel the main characters were a quartet, but the role of Barbara (Martha Hyer) was reduced considerably in Negulesco's film. She's a divorced woman raising a child on her own, desperate to disentangle herself from an office affair with Sidney (Donald Harron), another editor at the company. Barbara is less a fully-fleshed out character than a sad, cautionary tale – a woman whose options are considered limited and getting steadily smaller.

Jean Negulesco was born in Romania and had been an artist in Paris and New York City before he moved to California to work as a portrait painter. He became interested in movies and directed his own experimental films, which led to a contract at Paramount. He directed short films at Warner Bros. where he was assigned to direct Singapore Woman (1941), a b-picture, and by 1948 he was nominated for an Oscar for Johnny Belinda, a still-harrowing picture starring Jane Wyman as a deaf-mute who murders her rapist.

He moved to Fox, where he made Three Came Home (1950), Phone Call from a Stranger (1952) and Titanic (1953) before directing How to Marry a Millionaire, the film that probably defines his career. With this and his next picture, Three Coins in the Fountain (1954), Negulesco sealed his reputation as the Cinemascope director, uniquely able to tell stories using the technically challenging widescreen format.

As a director Negulesco understood his strengths and had a curious penchant for recurring themes. He had a flair for melodrama, and whatever the "woman's picture" had evolved into by the '50s. (Though he was no Douglas Sirk.) He also favoured stories with a trio of characters starting with How to Marry a Millionaire and Three Coins in the Fountain, which continued with the three couples in Woman's World (1954) and the co-workers in The Best of Everything. The Pleasure Seekers (1964), starring Ann-Margret, Carol Lynley and Pamela Tiffin, was a musical remake of Three Coins in the Fountain.

Martin Ritt was originally meant to direct The Best of Everything but left the production either because he didn't like the script or the casting of Suzy Parker as Gregg. Casting constantly changed in pre-production, and at different points Lee Remick, Diane Varsi, Joanne Woodward, June Blair and Audrey Hepburn were discussed, along with Lee Philips and Robert Wagner for men's roles. Other actors who went in and out of the cast included Jack Warden, Jean Peters, Lauren Bacall and even Margaret Truman, daughter of the former president.

It's hard not to imagine all the alternative scenarios, some of which may have produced a better film. Fifties supermodel Suzy Parker was a good choice for Gregg, whose beauty defines and undoes her, and her limitations ultimately help her portrayal of an actress who can't act. Diane Baker is plausible as the Colorado yokel striving to let some of the big city sophistication rub off on her.

And Hope Lange is a good if less than excellent Caroline. (Imagine Lee Remick in the role.) She manages Caroline's promotions from secretary to reader to editor, helped somewhat by the fine-tuning of her wardrobe during her ascent by costume designer Adele Palmer, who got an Oscar nomination. Her worst scene is one that defeats most actors, playing drunk when she goes on a bender with Mike after she's jilted by her fiancé.

Caroline's quick rise and Amanda's long tenure at the company suggests that there are opportunities for women in the business world – provided they're not using the office as a dating pool, or their wages to finance a wedding. Like Mary Agnes, who is just a year away from her nuptials when Caroline gets her job – it will take that long to pay off a $200 dress and a $75 negligee for the wedding night. (Her fiancé is saving to pay for furniture – "French provincial – in two rooms!")

During the war women filled the factories to power the war effort but were sent back to their homes when the men returned and the factories switched back to domestic goods. It didn't take long for the postwar boom to lure them out again, to offices where most of them were occupied in the sort of work – typing, stenography, filing, data entry – that would one day be computerized.

April is frank about looking for a husband in the city, while Gregg is using her job at Fabian to pay rent while waiting for her big break, which comes when she's cast by Jourdan's David in his new play after she spends the night with him. She's discarded just as quickly, his rejection sending her over the edge in just a few shots – signaled when the camera skews into off-kilter angles and Alfred Newman's score fills with eerie dissonance.

In the meantime playboy Dexter is pressuring April to sleep with him, which produces the expected result. She thinks he's taking her to a Maryland wedding in his Jaguar XK but he angrily reveals that they're on their way to an appointment with a doctor, for an "operation" that he'll nobly pay for. She jumps out of the car in the middle of Central Park, miscarries and ends up in the hospital; Dexter makes a big show of writing a cheque to pay for that as well, telling the nurse that April can keep the change.

Of all the terrible men in The Best of Everything Dexter is the worst, and Robert Evans does a convincing job with him, though he's still a mediocre actor lucky he found a place running movie studios. Jaffe, who seems to have been incredibly well connected even as a young writer, was rumoured to have written Dexter with Evans in mind, though the main source of this story is Evans himself, never a reliable narrator, especially with his own life.

Lange's Caroline finds herself drawn to bibulous, downbeat Mike, even though he constantly tells her that she'll never be happy pursuing a career instead of a family. Their tenuous romance cools briefly, however, when her ex-fiancé arrives in New York and asks her out to lunch.

She assumes that he's come to his senses, but Eddie admits that while he loves her and not his wife, he wants her as his piece on the side, to be maintained with an apartment of her own for when he's in New York overseeing a new office for his father-in-law's oil company. (Men could be sexual mercenaries as well as women, the picture implies, though the big difference was the potential pay out.)

Lange delivers a bitter rebuke, in a speech that's probably her best scene in the picture:

"What is it about women like us that make you hold us so cheaply? Aren't we the special ones from the best homes and the best colleges? I know the world outside isn't full of rainbows and happy endings, but to you, aren't we even decent?"

It's the raw spot in a picture that's largely cool, well-styled and mannered, where class cuts jaggedly through the growing conflict between men and women as their social roles were evolving faster than manners and convention could comprehend. Which would only get worse as the looming sexual revolution ramped up the velocity, though no one knew it at the time.

(And once again, imagine Lee Remick delivering those lines.)

The picture is as overcooked as most melodrama, but it has room for a bit of ambiguity, most notably with Brian Aherne's turn as Fred Shalimar, the eminence grise of Fabian, a veteran editor who constantly recalls his long-ago role in the career of Eugene O'Neill. He's also an old letch, a married man whose hands wander endlessly through the secretarial pool.

He asks April to work late taking dictation and answering letters, ordering up dinner before making a clumsy pass at a woman young enough to be his daughter. When she pushes him away, confused and embarrassed, he turns contrite, slipping the sandwiches into an envelope for her to take home, adding money for a taxi. And by the time April makes it to the elevators after rushing from his office, she pauses to consider with satisfaction that she's fended off her first wolf – exactly the sort of worldly experience that made her move to the city.

At an office party where he's only the most visible drunk, he forces himself on poor Barbara. Her erstwhile office beau Sidney pulls him off her and Mike leads Fred away as he mutters that, as a divorced woman, she has to expect this sort of thing. But he's also Caroline's champion, spotting her talent finding material in the office "slush pile" of manuscripts and getting her a raise and a new job as a reader – a promotion that Amanda makes it clear she opposes.

Caroline ends up with Amanda's office when the older woman suddenly leaves to marry a rich widower in St. Louis with two children, then gives up the job when Amanda returns, admitting that it was too late for her, and that she had "nothing left to give". In Jaffe's book Caroline is suddenly whisked away from Mike, Amanda and Fabian by her whirlwind romance with a movie idol who parachutes into the story; in the film she has a more ambiguous ending, running into Mike on the street outside the office, where their eyes meet and they tentatively head off together, walking down Park Avenue toward Grand Central.

Offices no longer look like they did in The Best of Everything. Most have far more women than men, though secretarial pools are gone, along with company picnics and drunken office parties. Human Resources departments make Fred Shalimars less likely (though not impossible), but the biggest change might be that nobody has to be in the office more than a couple of days a week, and when they are they might have to hunt for an empty desk.

Zoom meetings and remote work have created an office that's less like a society and more like social media. Cities might be full of skyscrapers with empty floors, but the Seagram Building is nearly full.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.