There's a bit of conventional wisdom among film nerds that the brief era between the introduction of sound and the enforcement of the Motion Picture Production Code in 1934 was a golden era for freedom of expression. Before moral scolds and killjoys like Joseph Breen and Will Hays were allowed to write the rules that Hollywood studios chose to follow to avoid regulation from above, movies were a crazy, sexy, transgressive free fire zone of what we'd now call progressive ideals.

"The best era for women's pictures was the pre-Code era," Mick LaSalle states outright in Complicated Women: Sex and Power in Pre Code Hollywood. "Before the Code, women on screen took lovers, had babies out of wedlock, got rid of cheating husbands, enjoyed their sexuality, held down professional positions without apologizing for their self-sufficiency, and in general acted the way many of us think women acted only after 1968."

Even Mark Meechan, the Scottish comedian and free speech advocate known as Count Dankula, said in a YouTube video about Pre-Code Hollywood that "art is so much better when it's allowed to push all of the boundaries when it's telling its story." So when the Code finally went away in the late '60s, he tells us, "Hollywood went on to produce a lot of amazing classics that would not have been possible if the Hays Code was still in place. Turns out censorship makes art suck. Who fucking knew?"

It's an attractive idea, and a plausible one based on assumptions right-thinking people are encouraged to share: nobody likes a prude, nothing good comes from rules set by men in suits, and creative people allowed to pursue their muse untrammeled will always produce beauty and wisdom.

But is this actually true?

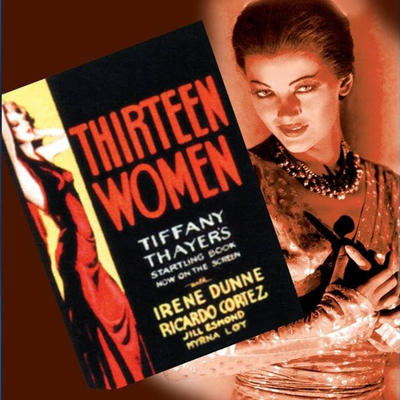

Thirteen Women came out in 1932, at the height of the Pre-Code era, and is one of perhaps a hundred pictures from the period that have been reissued on DVD in limited numbers to feed a simmering interest in the films made before the Production Code went into effect. It's a film fandom stoked by books like LaSalle's and by frequent TCM screenings of Pre-Code classics like The Divorcee, Three on a Match, Queen Christina and Trouble in Paradise.

The film was produced by David O. Selznick for RKO and was based on a bestselling novel of the same name by Tiffany Thayer. Thayer – a man, despite a given name associated these days with the '80s pop chanteuse who began her career performing in shopping malls – was an actor and journalist who co-founded the Fortean Society, whose membership included H.L. Mencken, Alexander Woollcott, Ben Hecht, Theodore Dreiser and Booth Tarkington.

The society celebrated the ideas of Charles Fort, an eccentric obsessed with phenomena like spontaneous combustion, poltergeists, UFOs, ball lightning and almost anything else that fell outside what was then explainable by science. His popularity and the Society directly lead to modern fascination with alien abduction, lost advanced civilizations and cryptids, staples of conspiracy and fringe pseudo-science. Thayer himself dismissed flying saucers but thought atomic weapons were a hoax, and during World War Two opposed civil defense measures like blackouts against air raids.

Somewhere amidst all his conspicuously nonconformist activities Thayer managed to write a bestselling novel in 1930 about a group of women – sorority sisters methodically destroyed by a former schoolmate who they had shunned. He was not a critical favorite or beloved of his better-received peers: Dorothy Parker called him a "writer of power" though added that "his power lies in his ability to make sex so thoroughly, graphically, and aggressively unattractive that one is fairly shaken to ponder how little one has been missing." F. Scott Fitzgerald simply called his work "slime" that attracted children in "drug store libraries."

But books like Thirteen Women sold well enough to attract the attention of Selznick, who assigned the film to French-born director George Archainbaud, who had made his first picture in 1917. His career highlight was probably The Lost Squadron, a flop made just after Thirteen Women, which starred Richard Dix and Joel McCrea as WW1 aces turned stunt pilots and Erich von Stroheim as an evil movie director. He would end his career making oaters for Gene Autry's production company and episodes of TV westerns like Buffalo Bill Jr. and Annie Oakley.

Thirteen Women was adapted with a very heavy hand for the screen by Bartlett Cormack, who wrote Cleopatra (1934) for Cecil B. DeMille and Fury (1936) for Fritz Lang, and Samuel Ornitz, whose career highlight was co-writing the original Imitation of Life (1934). No one would call Thirteen Women anyone's best work.

The film begins with a quote from pages 94 and 103 of Applied Psychology, a 1920 academic textbook written, we are told, by Columbia University professors Harry Hollingworth and Albert Poffenberger. This unimpeachable evocation of authority informs us that:

"Suggestion is a very common occurrence in the life of every normal individual...Waves of certain types of crime, waves of suicide, are to be explained by the power of suggestion upon certain types of mind."

Suitably chastened to accept what follows as serious stuff, the camera follows a letter from the mail sorting car on a train to its recipient – June Raskob (Mary Duncan), one half of a pair of twin acrobats working for a circus. The sender is one "Swami Yogadachi" who has enclosed a horoscope that predicts her complicity in the imminent demise of her sister May (Harriet Hagman).

The Swami's horoscopes have been mailed to a group of women who once formed a clique at St. Alban's Seminary, a finishing school just north of San Francisco. They all predict death, jail and madness, and it doesn't take long before his predictions start coming true, starting with poor June and May Raskob and continuing to Hazel (Peg Entwhistle), who shoots her husband.

We meet Swami Yogadachi (C. Henry Gordon) in New York City, where he's under the spell of Ursula Georgi (Myrna Loy), his "secretary", and even more troubled by visions of both of them ending their lives mangled on train tracks, though his expiry date is fast approaching. Ursula is the obvious villain of the piece, a Eurasian femme fatale (half-Hindu and half-Javanese, apparently) with mesmeric powers that she quickly puts to use, entrancing the swami to swoon off a subway platform to his death.

By the time Thayer wrote his book the West had been thick with swamis and pandits of varying pedigrees for decades, There was Swami Vivekananda, Madame Blavatsky, Jiddhu Krishnamurti and Meher Baba who arrived in America in 1931 and became a sensation in Hollywood, meeting with stars like Gary Cooper, Tallulah Bankhead and Tom Mix. A reception was hosted for him at Pickfair by Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks. Jr.

California was a magnet for these gurus; in his book Nirvana Express: How the Search for Enlightenment Went West, Mick Brown writes how it "was the state of boomers and boosters, lured by the promise of a new life and new freedoms – a utopia that offered fertile ground for religious proselytizers, cranks, self-styled prophets, crackpots and frauds of every denomination and none."

Writer Louis Adamic, author of the 1927 book The Truth About Los Angeles, described the city's society as dominated by "Big Men...the high priests of the Chamber of Commerce" surrounded by "a mob of lesser fellows, thousands of minor realtors, boomers, promoters, contractors, agents, salesman, bunko-men, office-holders, lawyers and preachers" whose "wives gather in women's clubs, listen to swamis and yogis and English lecturers, join 'love cults' and Coue clubs in Hollywood and Pasadena..."

At the heart of this circle of school friends is Laura Stanhope (Irene Dunne), a rich widow living with her young son. Bolstered by her irreverent and sexually adventurous friend Jo (Jill Esmond), she scoffs at the Swami's predictions even as they begin thinning out their peer group, including poor Helen (Helen Dawson Frye), a mother grieving for her dead son, pushed to suicide on a train by Ursula, who turns out to have been an acquaintance from St. Alban's, blackballed by the group of girls.

Laura doesn't know it but Ursula has already infiltrated her family; her chauffeur Burns (Edward Pawley) is under the same sexual spell she cast on the Swami. Her nemesis regards destroying Laura as the ultimate goal – a humiliation of the "straight-thinking, oh-so-rational Anglo Saxons."

She tries and fails to poison Ursula's son with a box of poisoned candy, then persuades Burns to give the boy a birthday gift – a rubber ball with an explosive centre. She's foiled by police sergeant Clive (Ricardo Cortez), who has taken a personal interest in the threats to Laura and her son, and employs an arsenal of modern science and technology like lab tests and wire photography.

By the time she made Thirteen Women Loy's career had been full of these sinister vamps, typecast as dragon ladies and Mata Haris despite her solidly European background and Montana childhood. She was a "Vamp" in Finger Prints (1927), a "Mulatta" in The Heart of Maryland (1927), "Girl in China" in Howard Hawks' A Girl in Every Port (1928), a dancer and slave girl in Michael Curtiz' Noah's Ark (1928), Yasmani in John Ford's The Black Watch (1929), Nubi in Alexander Korda's The Squall (1929) and Morgan le Fay opposite Will Rogers in A Connecticut Yankee (1930).

The pre-Code era gave her occasional breaks from typecasting, and while she played a New York socialite in Ford's Arrowsmith (1931) and Becky Sharp in Vanity Fair (1932), her next role after Ursula in Thirteen Women was Fah Lo See, the sadistic daughter of Boris Karloff's villain in The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932). Thankfully she would only have to wait two more years for a pair of roles opposite William Powell, in W.S. Van Dyke's Manhattan Melodrama and The Thin Man, to achieve the stardom she deserved and freedom forever after from typecasting.

She only gets fourth billing in Thirteen Women, but her Ursula is really the centre of the picture and the instigator of all the action. It's tempting to call her the film's de facto star, but that's only because everyone else is so undeniably awful, including poor Irene Dunne.

By the time Thayer's novel had been boiled down for the screen it had already shed much of its lurid melodrama. Notably pared down was Hazel Cousins, the part played by Peg Entwhistle; in the book she was a beauty so stunning that she repelled men, who were either intimidated by her looks or assumed that she must be married. She becomes a lesbian who dies in a tuberculosis sanitarium, starving herself to death after being abandoned by her lover and seduced by the wife of her doctor.

This was too much even for pre-Code Hollywood, apparently, and in Cormack and Ornitz' screenplay she was transformed into a wife who stabs her husband in a jealous rage and ends up in prison. But the film was drastically cut in the editing room to barely an hour; two of the thirteen doomed women were dropped entirely and Entwhistle's scenes were trimmed from a reported sixteen minutes to a "blink and you'll miss it" cameo.

Entwhistle, a British stage actress, had suffered through a tough career, getting good notice in shows that either flopped or failed. She was in Los Angeles starring opposite Billie Burke and Humphrey Bogart in Romney Brent's The Mad Hopes when she caught the attention of RKO and was cast in Thirteen Women. But she was spared the humiliation of seeing how little of her remained in the picture by her suicide; a month before the film's premiere she made headlines by jumping off the Hollywood sign.

The pre-Code era produced its share of classics, though most of those still suffer from everything that made early sound pictures hard to watch today. There's the awkward, inelegant camerawork for one; there were geniuses who could overcome the harsh limitations forced on the medium by bigger, heavier movie cameras and the unfamiliar demands of microphones and recording technology. But George Archainbaud was no genius.

And neither were Cormack and Ornitz, whose script is on par with so much screenwriting from the era, evoking second-rate theatre and groaning under the weight of exposition. Which makes it tempting to excuse the actors, who nonetheless declaim their lines with varying degrees of mannered, mid-Atlantic delivery, enunciating painfully to make sure they can be heard by the primitive sound recorder.

We know Irene Dunne was capable of much better, and thankfully we have films like The Awful Truth, My Favorite Wife and A Guy Named Joe to remind us. Sadly, though, nearly every actress in the film who isn't Myrna Loy is in thrall to the kind of overwrought emoting that worked in silents and persisted well into talkies and the pre-Code era (and would linger in b-pictures for years to come).

Alone in her room on the train with her grief and a loaded pistol, Kay Johnson's Helen dallies with the gun and confronts her torment in a mirror before deciding to end it all. It's the kind of performance that makes so many dramas, thrillers and romances from the first half of the '30s seem like reels of tryouts for summer stock Lady Macbeth.

And there's nothing in Thirteen Women to prove LaSalle's thesis that pre-Code films showcased and celebrated liberated women without qualification or excuses. Dunne's heroine is a virtuous widow, devoted to her son, while her clique of schoolfriends (with the exception of Jill Esmond's Jo) descend into varying degrees of what Victorians would have called hysteria, that uniquely female ailment.

It's only Loy's Ursula who embodies the unencumbered modern woman in LaSalle's thesis; she even gets to play a race card of sorts, bitterly complaining about her treatment as a "half-caste" in a "world ruled by whites." But she's also a psychopath – a murderer happy to kill a child with poison and bombs to punish its mother.

Thirteen Women is celebrated today as one of the earliest women's ensemble pictures, but it's a pretty dismal example next to films like Stage Door and The Women, made when the Code was being enforced with peak vigour. Great actresses emerged from the pre-Code era, to be sure – names like Bette Davis, Joan Crawford and Barbara Stanwyck. But like Loy and Dunne they'd flourish in Code pictures, mostly because scripts, roles and directors strangely improved in a system where limitations, arbitrary and ridiculous as they might have been, were a challenge to be played with, subverted, defied or overcome.

There's no denying that there are some great pre-Code pictures, though Thirteen Women certainly isn't one of them. But it often seems like our celebration of pre-Code Hollywood is naïve and overplayed, like feigning ironic outrage that our grandparents cursed and had sex, or that the world on the far side of our shared myth of the '50s is more complicated than we thought.

This feels more like a failure of imagination than proof that the Production Code "ruined" movies. Sometimes you need to watch a picture like Thirteen Women to remember that perfect creative freedom can inhibit genius just as surely as it provides cover for laziness and mediocrity.

This week saw the fourth anniversary of the death of Kathy Shaidle, the originator of the weekly film column at SteynOnline. I'd say that it made me reflect on all the things she might have said about the Biden era, the Trump reprise and so many other topics, but the truth is that I think about that all the time. Much as I have enjoyed writing this column, now nearing its 200th installment, I would be happier if the opportunity had never presented itself and Kathy were still here in this space. You are missed.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.