Early on in The Riddle of the Sands, Erskine Childers' 1903 novel about espionage and conflict between the Great Powers, there's a moment that's either wildly prescient or a statement of simple, brutal facts. Carruthers, a minor employee in the British Foreign Office, has sought to escape London's late summer doldrums by accepting an invitation to join Davies, an old friend from Oxford, on a sailing expedition around the Frisian Islands, where the coasts of Germany and Denmark meet.

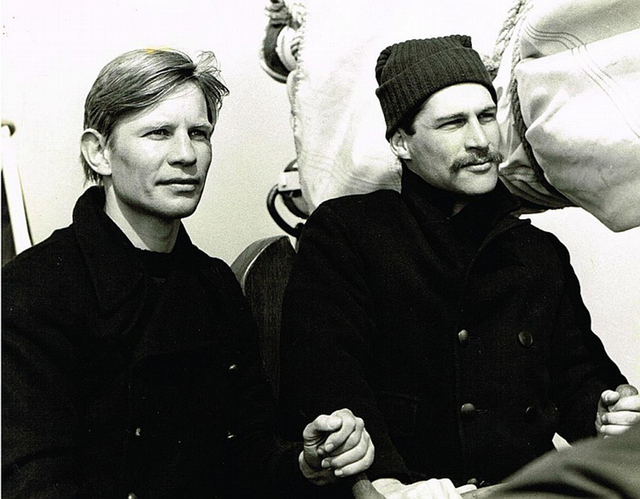

Used to wearing white flannel and blue blazers on luxurious pleasure yachts, Carruthers is shocked to discover that the Dulcibella, Davies' boat, is cramped and well-used, and that his eccentric friend expects him to put in some hard graft helping him crew it around the vast tidal mud flats behind the islands of Juist, Norderney and Borkum. They sail past Dybbøl, the scene of the climactic battle of the Second Schleswig War in 1864, where Prussia defeated Denmark and annexed a whole new stretch of coastline.

The war unified the German states into a single country that was now demanding respect from the rest of the world, and Davies for one is impressed.

"Germany's a thundering great nation," he tells Carruthers. "I wonder if we shall ever fight her." In just over a decade Davies would get his answer, after Childers' own novel had helped stoke the simmering geopolitical tension that would explode into global war in August of 1914.

Back in the distant days of 2019 when Mark undertook a serialization of Childers' only novel here, he wrote that "there was a sense in the air that sooner or later Europe would come to war. Did Britain appreciate the threat from Imperial Germany? No, thought Childers. London looked out into the world, to its vast empire and the oceans guarded by its mighty navy, not over its shoulder to a fractious continent and its parochial squabbles."

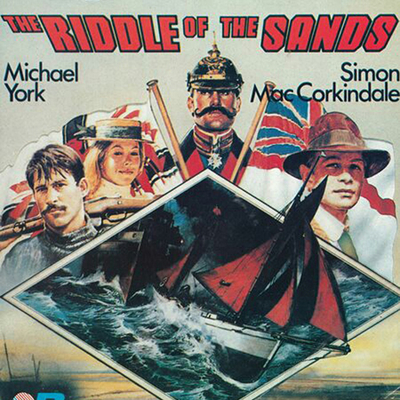

Childers' book not only forced the British military to contemplate the threat of German invasion, it was an enormous and abiding bestseller. Remarkably, though, it didn't appear on movie screens until 1979, when the Rank Organization adapted it for the cinema under director Tony Maylam, at that point only known for sports and music documentaries.

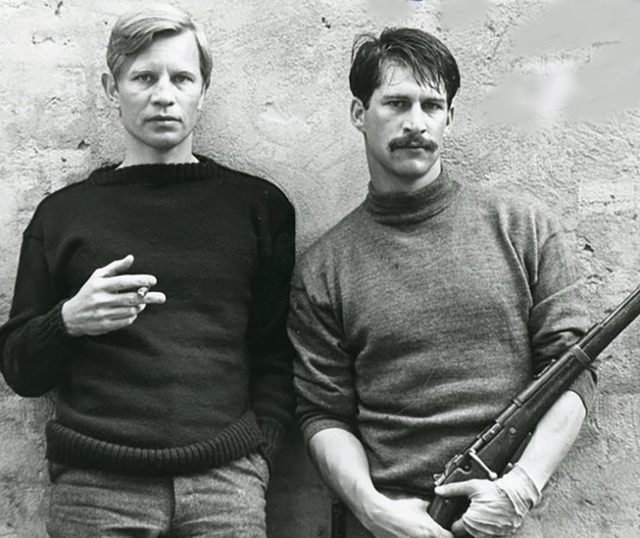

The film begins with Carruthers (Michael York) staring out a window and declaring, his bitter languor dripping with privilege, that he was "bored – utterly and profoundly." Cut to the opening credits, which play over Davies (Simon MacCorkindale) on board the Dulcibella, adjusting sails and manning the tiller on the open seas, a vision of the gentleman adventurer.

It's 1901, and somewhere off the Frisian Islands he's watching and being watched by the Medusa out of Hamburg, a far more opulent yacht. He's visited by Clara (Jenny Agutter), the daughter of the Medusa's owner, Dollman (Alan Badel), an avid sailor and owner of a marine salvage company. She's obviously been sent to discover what the young Englishman is doing in German waters and invites him for dinner aboard the Medusa with her father, her bored and bibulous stepmother (Olga Lowe) and Von Brüning (Jürgen Andersen), a Kaiserliche Marine officer.

His self-assigned mission to update Admiralty charts of the coastline is regarded with suspicion, even in peacetime, but a flirtation develops with Clara, who becomes a frequent visitor to the Dulcibella. But when Dollman invites Davies to sail with him for Hamburg in a gale and nearly runs the Englishman aground on a shoal, he sends a letter inviting Carruthers, a fluent German speaker with Foreign Office connections, to join him, along with a shopping list of supplies and equipment.

Carruthers' arrival is the only palpably comic sequence in Maylam's film; and begins with a shot of York's foot, shod in a pair of polished white and light brown boots, stepping down from the train after his pile of luggage. Davies manhandles the cases and packages down the dock to his boat, which is obviously of an order of magnitude smaller and meaner than Carruthers had hoped. There's considerable business around fitting everything into the tiny cabin, through a hatch that will not fit Carruthers' portmanteau.

A miserable night follows, after which it seems that Carruthers is on the verge of heading back to London, but in Childers' book he has a revelation that more than resigns him to the uncomfortable reality of the voyage he has agreed to undertake with Davies:

"Whether it was something pathetic in the look I had last seen on his face – a look which I associated for no reason whatsoever with his bandaged hand; wither it was one of those instants of clear vision in which our separate selves are seen divided, the baser from the better, and I saw my silly egotism in contrast with a simple generous nature; whether it was an impalpable air of mystery which pervaded the whole enterprise and refused to be dissipated by its most mortifying and vulgarising incidents – a mystery dimly connected with my companion's obvious consciousness of having misled me into joining him; whether it was only the stars and the cool air rousing atrophied instincts of youth and spirits; probably, indeed, it was all these influences, cemented into strength by a ruthless sense of humour which whispered that I was in danger of making a mere commonplace fool of myself in spite of all my laboured calculations; but whatever it was, in a flash my mood changed."

This passage gives you some idea of the Edwardian pace of Childers' prose, the like of which you'd never find in any modern espionage thriller descended from The Riddle of the Sands. It's a reflection of a society where "manners maketh the man," and the high-status manifestation of that stiff upper lip that was considered both virtue and vice of Britain's class system, depending on where and when you looked at it. In any case, from this point on Carruthers is fully bought into Davies' still-unexplained reason for the unexpected invitation.

Robert Erskine Childers was born into privilege and made his reputation as a defender of the system that gave him so much. Born in Mayfair, his parents died of tuberculosis and he was sent to live with his mother's family in County Wicklow, where he developed the first stirrings of sympathy with the Irish under British rule. After attending Cambridge he obtained a post as a junior committee clerk in the House of Commons, before enlisting as an artillery officer in the Boer War.

A keen sailor, he made his first journey to the Frisian Islands in 1897 with his brother Henry and Ivor Lloyd Jones, a friend from Cambridge, on the Vixen, a 30-foot cutter. It was the voyage that would inspire The Riddle of the Sands, which was published in May of 1903 and was an immediate success,

It was not the first novel to imagine an invasion of England. In The Battle of Dorking, published in 1871, George Tomkyns Chesney imagined a German-speaking "Other Power" who destroy the Royal Navy with torpedoes and land an army in Sussex. And just six years before Childers published his book The Great War in England by William Le Queux depicted a French-led coalition invading Britain, which is saved at the last moment with assistance from their German ally. In the imagination of England and its writers it seems that enemies – and friends – were everywhere and even at its zenith the Empire was a fragile proposition.

Aboard the Dulcibella, Davies tells Carruthers his suspicion that Dollman isn't German but English, and that his salvage business is a cover for something bigger and more sinister, based on how closely he works with Von Brüning and the activity of the German military in his vicinity. When the two men don't take the hint that they should leave they become the object of overt surveillance and harassment, when two German sailors try to board the Dulcibella one morning while Davies is away and the boat is anchored on the mud flats at low tide.

Under cover of fog they row out to an isolated island to discover an abandoned brickworks being used to manufacture barges. And everywhere they moor their boat they find the Medusa, Dollman and Clara, who is either the most successful agent of surveillance or a growing ally in their search for the truth of what's going on in the Frisian Islands.

An old book left by Clara, written by a Royal Navy officer, Lt. Thomas, reveals Dollman's true identity, and a ruse where Carruthers pretends to leave for London leads to a revelation that the Germans are rehearsing an invasion of Britain involving towed barges loaded with soldiers, to be sent out en masse from uncharted passages through the Frisian mud flats. Hiding in a lifeboat on a German tug, Carruthers is amazed to see that no less than Kaiser Wilhelm II (Wolf Kahler) is there to oversee the rehearsal.

Conflicted loyalties would come to define Childers' life after The Riddle of the Sands. His Irish upbringing and his experience in South Africa during the Boer War created a growing sympathy for national self-determination and Irish Home Rule, and by 1914 he was using his yacht to smuggle rifles from Germany to the rebels in Ireland.

But when the conflict he had predicted came to pass and war broke out that year, he received a telegram in Dublin, where he was writing propaganda for the Irish cause, inviting him to enlist in the Royal Navy, on the insistence of no less than Winston Churchill. His first job was to help write an invasion plan of Germany, and his experience with seaplanes and naval aviation saw him transferred to the newly formed Royal Air Force near the end of the war to work as an intelligence officer for bombing operations.

Demobilized in 1919, he returned to Ireland and volunteered his services to Sinn Féin. He became a propagandist for the cause and traveled to London in 1921 as Eamon De Valera's secretary to negotiate with Lloyd George. But when the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed Childers denounced it, and when civil war broke out the next year he was on the run from the new national government with the anti-treaty forces. (I have always observed sadly that only the Irish could conclude a successful, centuries-long fight against British occupation by going to war with themselves. Self-sabotage is a national pastime.)

Even while working as a propagandist for De Valera's forces against the Free State he was considered an outsider as an Englishman, distrusted by many of the officers and soldiers whose cause he championed and suspected of being a double agent. But he was captured by government forces and put in front of a military court martial for carrying a pistol – given to him by no less than Michael Collins, leader of the government's military forces, back when they were fighting on the same side.

Childers was sentenced to death and appealed the sentence, but before his appeal could be considered he was shot by a firing squad on November 24, 1922. His last words were apparently "Take a step or two forward, lads, it will be easier that way." His son, Erskine Hamilton Childers, would become the fourth president of the Irish state in 1973, right after Eamon De Valera held the office for nearly a decade and a half.

This was far in the future for Childers when he wrote The Riddle of the Sands, though Davies – who was meant to stand in for the author in the book and voice his opinions – is enthusiastic in his admiration for the Germans. "They've licked the French, and the Austrians, and are the greatest military power in Europe," he proclaims to Carruthers. "It's a new thing with them, but it's going strong, and that Emperor of theirs is running it for all it's worth. He's a splendid chap, and anyone can see he's right. They've got no colonies to speak of, and must have them, like us."

Clara had a minor part in Childers' book, which was expanded for the movie to provide a palpable but notably chaste love interest for Davies, and nobody would have objected to seeing more of Jenny Agutter, back in Victorian period costume for the first time since The Railway Children in 1970. The Kaiser didn't appear in the book at all except in a hint and was interpolated to provide a more sinister baddie than either Dollman or Von Brüning.

Maylam's film takes a cue from the leisurely prose of Childers' book, telling the story in an unrushed way, the pace set by the wind and waves that propel the Dulcibella from port to anchorage to port. It becomes more urgent when the Kaiser alights from his carriage just after a company of spike-helmeted riflemen march down the cobbles of a locked-down port town at night and take their place in the bottom of a barge like tin soldiers in a Christmas gift box.

At first it seems like the third-billed MacCorkindale is the action hero of the film, but York's Carruthers is given his chance to sneak into enemy territory and by the time the Kaiser appears we've seen him act as bait and change costumes, tailing his German pursuers up and down the railway before knocking enemy sailors overboard, commandeering the tug and sabotaging the invasion rehearsal. He even uses his imperative German to command the Kaiser himself to loose a lifeboat's line so he can make his escape. (Like any good German, we're meant to understand, he knows when to follow orders.)

Clara isn't troubled by divided loyalties at the end, disowning her father's plot while she convinces Carruthers and Davies to show him mercy. Wounded by Davies' shotgun before he had a chance to execute Carruthers, Dollman/Thomas and his wife are allowed to sail the Dulcibella back to Germany while his daughter and the two Englishman take the Medusa to Britain with his plans for the invasion.

But the Dulcibella is spotted by Von Brüning and his patrol boat, the Blitz, and is about to be run down when Dollman and his wife are spotted on the deck. Von Brüning begins steering away but the Kaiser puts his one good hand on the wheel and turns it back to destroy the little boat and everyone on board. It's an ending that, as film blogger Roderick Heath writes, "nudges the film closer to the more familiarly cynical territory of 1970s thrillers: state power wielded with exterminating precision to erase an inconvenience."

The success of Childers' book prompted a call in parliament and the press to fortify Britain against invasion from the North Sea; Churchill himself claimed that it inspired the building of naval bases at Invergordon, Rosyth and Scapa Flow, though this has been disputed, with plans for Rosyth on the Firth of Forth apparently underway before The Riddle of the Sands was published.

In 1910 two amateur sailors and Royal Navy officers, Bernard Tench and Vivian Brandon, were captured while making notes about German military installations on the Frisian coast and sentenced to jail for four years by a military court, though the Kaiser pardoned them after three years and they joined the intelligence section of the Admiralty when war broke out.

The film was unfortunately not a success for the Rank Organization, and along with Eagle's Wing and The Lady Vanishes contributed to a £1.5 million loss and was one of the last movies made by Rank during one of many tumultuous periods in British film production. The picture wouldn't see release in the U.S. until 1984.

One of my dictums is that every film, even a period film, is about the period it was made, not the time when it's set, though The Riddle of the Sands might be the exception that proves the rule. At a stretch you might suggest that it reflects Cold War paranoia, but despite the ending there's nothing in the film that strives to make the connection between the Kaiser's Germany and the Soviet Union explicit. With its placid echoing of the unhurried tone of Childers' book, Maylam's film occupies a place in film history not unlike the Dulcibella, resting on the silvery tidal flats in the cool northern sun like an artifact.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.