Something was happening to the Hollywood Western in the 1950s. Television had killed off the serial and the b-movie "oater" – Republic Pictures, a major name in both, ceased production in 1958 – and as westerns became a product of the big studios and producers, they took on the look of prestige productions, with big stars, epic cinematography that showcased technological innovations like Cinemascope and Vistavision, and weighty social themes.

The decade began with Delmer Daves' Broken Arrow and Jimmy Stewart as a white cowboy and friend to Jeff Chandler's heroic Cochise. It was a hit and got three Oscar nominations, which meant that Hollywood would make more films like it, and the last year of the decade would see the release of Daves' The Hanging Tree (Gary Cooper as a gunslinging doctor against a lawless town), Edward Dmytryk's Warlock (Henry Fonda and Richard Widmark battle over what law and order means in an unfortunately-named town) and No Name on the Bullet (men in a town summon the courage to confront a young gunfighter played by Audie Murphy).

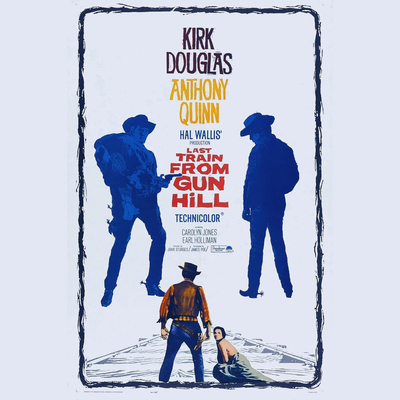

And then there was Last Train from Gun Hill, John Sturges' loose retelling of a story that echoed High Noon, Forty Guns, Budd Boetticher's Ride Lonesome and any other western involving lone lawmen fighting outlaw gangs, anti-Indian bigotry, revenge at all cost and frontier towns being forced to choose between fear and justice. Which by 1959 pretty much meant any Hollywood western – from the moment the credits faded on some sunbaked widescreen vista one or more of these themes would be struck and, hopefully, resonate into a satisfying chord.

Sturges' film begins at a point we're meant to understand is very near the end of the lawless frontier. Children in a small but pleasant town goad their local lawman, U.S. Marshal Matt Morgan (Kirk Douglas), into retelling the story of a gunfight that made his reputation, back in "the olden times." Morgan's deputy jokes about this being barely nine or ten years ago, but one of the boys complains that "You don't even get to hear a gun in the territory anymore."

Morgan is reaching the dramatic high point of his story when his son Petey rides into town on a strange horse and tells him about the tragedy we've already watched unfold in the opening scene after the credits. Morgan's Cherokee wife Catherine (Israeli actress Ziva Rodann) and Petey were riding out to visit her family on the reservation when they were chased down by two young cowboys drinking by the side of the road – Rick Belden (Earl Holliman) and his buddy Lee (Brian G. Hutton).

Catherine slashes Rick across the face with her horsewhip during the chase but when their carriage overturns she's cornered by the men. She tells Petey to take one of their horses and run but is raped and murdered by the cowboys – a sequence that Sturges tastefully films so that the crime is hidden or obscured. Morgan arrives too late to save her but notices the very fine saddle on the horse his son stole with the initials "C.B." figured in silver.

Morgan might not know who killed his wife but he knows who the saddle belongs to – his old friend Craig Belden (Anthony Quinn), a running buddy from their lawless days, now a rich cattle baron whose vast acreage takes in the town of Gun Hill. He sets off for Gun Hill with the saddle and two arrest warrants and the sort of steely resolve that you expect from Kirk Douglas. His father-in-law wants to take revenge on the killers "the Indian way" – slow and painful – but Morgan intends to obey the letter of the law.

He's on the train to Gun Hill, the saddle parked in the seat facing him, when a lone woman enters the carriage to wolf whistles and hoots. Linda (Carolyn Jones) takes the seat next to Morgan, the only man who isn't ogling her, but discovers that she enjoys his curt indifference just as little. She recognizes the saddle, though, and lets him know she's getting off at Gun Hill as well before moving to a different carriage.

The train arrives at Gun Hill on the single track running through the centre of town, where Belden has sent his men Beero (Brad Dexter) and Skag (Bing Russell) to meet Linda and take her to his ranch. She declines their offer, but they recognize the saddle Morgan is carrying and ride back to the ranch to let Belden know.

According to Rick it was stolen by horse thieves while he and Lee were having a bit of fun in Morgan's town, with the woman who gave Rick the scar on his cheek. Belden doesn't believe his son's story – he knows that Morgan runs a tight town where horse theft is rare and wonders why they never bothered to report the theft – but he indulges his son with only one proviso: that he get that saddle back.

The old friends are reunited at Belden's ranch, Belden is reunited with his saddle and repeats an offer he'd made years ago to make Morgan a partner in a prosperous business, but the lawman declines. He tells him why he's there and, presuming that the men Rick says stole his horse killed Morgan's wife, offers to help his friend find the murderers.

But Morgan mentions the scar and, reading his old friend too well, immediately knows that Belden's son is the killer. He leaves promising to bring Rick to justice, while Belden promises that he'll never take his son away. Belden confronts Rick and Lee when they return, asking why they lied; when Lee's only excuse is that it was "just some squaw" Belden knocks him flat and has him run off the ranch.

Back in Gun Hill news has traveled fast. The local sheriff explains to Morgan that Belden owns the town, and that he takes "the long view" that it isn't in his best interests to help the marshal serve the two arrest warrants he's brought for Rick and Lee. The townspeople are just as hostile but Linda, sipping tea in one of the many saloons, is happy to tell him just which one Rick Belden prefers.

By now Morgan is in full John Wick mode; he tracks Rick down, climbs a tree to get into the saloon through a window in the brothel upstairs, knocks the young man out and carries him downstairs over his shoulder. After a brief exchange of fire that kills two of Belden's men and wounds Skag, he locks Beero and the rest in a cupboard and carries Rick across the street, checking into a room at the hotel where he handcuffs the young man to a bed and waits for Belden and his men or the 9 o'clock train out of town – whichever comes first.

Belden and his men arrive first, of course, and begin a siege of Morgan in the hotel, starting with an exchange of gunfire with the dead shot marshal taking out more of Belden's cowboys, brought to an end when he kicks the bed with Rick in it up against the hotel window. Much of the simmering drama of Sturges' film plays out during the siege, where the two friends realize that one of them likely won't survive till the train arrives, the odds firmly against Morgan.

John Sturges is a director whose reputation has not been buffed up with the decades, even though he directed two pictures (The Great Escape, The Magnificent Seven) that appear on countless "best film" lists, and others (Bad Day at Black Rock, Ice Station Zebra, Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, The Eagle has Landed) that get called "must see" or "overlooked" or "essential". But his name is still a tough answer to trivia questions only real film geeks will get.

An interview in True West magazine with Glenn Lovell, author of the only decent biography of the director (Escape Artist: The Life and Films of John Sturges), even begins by stating that "John Sturges was not a great filmmaker" and that "he's never been placed up there in the top branches with the certifiably best directors – Ford, Hawks and the like. No one would argue that he belongs there, not even his staunchest champions."

Lovell says he wrote the book "because the scholarship on Sturges has been so shoddy. There are tons of movie books that confuse John Sturges with Preston Sturges, for example, and even the IMDB, which has become a kind of a filmgoer's bible, has him born in 1911, whereas he was born in 1910. Frank Sinatra Jr., on TCM just a few months ago, was talking about Sergeants Three (a movie Sturges directed starring the Rat Pack) and he said, 'this was directed, of course, by John Sturges, who as we all know, is Preston Sturges's son!'"

John Sturges was not Preston Sturges' son. He was born in Oak Park, Illinois, started his Hollywood career as an editor and spent the war making documentaries and training films for the U.S. Army Air Force. He began his directing career, as so many in his generation did, with a film noir, The Man Who Dared (1946), making several more before his first western, The Walking Hills (1949), starring Randolph Scott.

He had a journeyman's career, working with stars like Barbara Stanwyck, June Allyson, Spencer Tracy, Howard Keel and William Holden until 1955, and Bad Day at Black Rock. Described as a "film noir neo-western", with Tracy as a man looking for justice in a town full of racists, a bleak whistle stop in the middle of a purgatorial desert landscape shot by Sturges in pitiless Cinemascope.

Tracy was too old for his role as a one-armed veteran who can toss a bigger, younger man to the floor in a bar fight, but the picture opened to good reviews and better box office. Sturges had hit a nerve with his story about anti-Japanese racism in a town closing ranks around its collective guilt. (Though no Japanese characters are seen in the film.) Writing in the New Yorker, Pauline Kael set the critical tone for Sturges' reputation by calling it "crudely melodramatic" but "a very superior example of motion picture craftsmanship."

If there was a problem with Sturges' career you could say it was a lack of consistency. After finishing Bad Day at Black Rock he released Underwater! the same year, which featured Jane Russell diving for sunken treasure, made (no surprise) for Howard Hughes' RKO. This was followed by a historical adventure picture (The Scarlet Coat) and a western (Backlash) before he made Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, with Kirk Douglas as Doc Holliday and Burt Lancaster as Wyatt Earp.

This was followed by a western flop (Saddle the Wind), a moderately more successful one (The Law and Jake Wade) and an adaptation of Hemingway's The Old Man and The Sea starring Tracy – a film that would be abide via drastically expurgated versions in middle school English classes for two generations until Hemingway became too problematic for modern educators.

Between Last Train from Gun Hill and The Magnificent Seven he made the first of his Rat Pack films, Never So Few, starring Frank Sinatra. Between The Magnificent Seven and The Great Escape Sturges directed By Love Possessed, Sergeants Three and A Girl Named Tamiko. After The Great Escape came The Satan Bug, a sci-fi espionage picture, and two westerns – The Hallelujah Trail and Hour of the Gun, another run at the O.K. Corral story, with James Garner as Earp and Jason Robards as Holliday.

Never an auteur, Sturges was instead a good soldier – a director for hire who could be relied upon to make watchable pictures with the material he was given, on time and on budget except in exceptional circumstances (he quit Le Mans when the picture started spiraling out of his control) and until he apparently lost interest in making pictures, right when filming wrapped on The Eagle Has Landed, his last movie.

Michael Caine, the star, was excited to work with Sturges, until he was on set and the director "informed me that, now that he was older, he only ever worked to get the money to go fishing, which was his passion. Deep-sea fishing off Baja, California, he added, which was very expensive. The moment the picture finished, he took the money and went."

"Producer Jack S. Wiener later told me that he never came back for the editing nor for any of the other post-production sessions that are where a director does some of his most important work. The picture wasn't bad, but I still get angry when I think of what it could have been with the right director. We had committed the old European sin of being impressed by someone, just because he came from Hollywood."

Thankfully Sturges was still fully engaged in his work when he made Last Train from Gun Hill, which deserves a place among his best (though probably not his greatest) pictures. He gets superb performances from his leads: both Quinn and Douglas are more restrained versions of themselves, and Douglas in particular avoids characteristic emotional histrionics or scenery chewing.

But the best performance comes from Jones, known today mostly for her Morticia on The Addams Family. Her career on the big screen is notable for small roles in good films (The Big Heat, The Seven Year Itch, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Man Who Knew Too Much) and big roles in less memorable ones (Johnny Trouble, Baby Face Nelson, A Hole in the Head) and the curious distinction of being the love interest in what's probably Elvis Presley's best picture (King Creole).

Her Linda is Belden's girl, though she was on that train because he'd sent her to the hospital after a particularly severe beating, prompted by rumours spread by his son. The implication is that Linda was – or is – a prostitute, and though it's never stated outright it's impossible to ignore. She constantly refers to an awful childhood and a hard life and pleads the case that Belden get his men to respect "her girls" who work in Gun Hill's brothels.

She doesn't have much hope that Morgan will make it to that train with Rick, and wistfully refers to an old beau who Morgan reminds her of – an idealist who's buried in Gun Hill's cemetery. She hates how the town is too scared to help Morgan get justice for his wife, and how she's just as scared as they are.

"The human race stinks," she says. "I'm practically an authority on that subject."

But she finds the courage after getting Lee to tell her what really happened to Morgan's wife, and smuggles a sawed-off shotgun to him while he prepares to make his desperate break for the train station. Once discovered she defiantly tells Belden and the town that she hopes Morgan uses the gun, to deliver Lee to the hangman, to kill him or enough of Belden's men to end his hold on Gun Hill – a fallen place, like the town whose name gives Warlock its title, or the one that Clint Eastwood paints red in High Plains Drifter.

If the film has a message – and it strives to let us know that it does – it's that the frontier is doomed as long as it's a world without women. Belden knows his son is not just a bully but a coward and admits to Morgan that he didn't raise him as well as he might if his wife hadn't died. But he persists in his brutal version of parenting nonetheless, forcing Rick to take a swing at Beero when the cowboy insults him, knowing that the young man doesn't stand a chance against the bigger, tougher older man.

Morgan's town is shown as a decent place to raise children, while they're entirely absent from the streets of Gun Hill. Rick and Lee embody the proverbial weak men made by good times, created by strong men who triumphed during hard times. But in Sturges' film the cycle is generational, not measured in centuries.

In one of the movie's best scenes Morgan tells Rick, shackled to the hotel bed, what will happen to him during the long process from arrest to trial to sentencing to execution, spelling out in detail the second-by-second torments of death by hanging. It's the kind of scene Douglas might have delivered with near hysteria in another picture, but Sturges keeps him contained, a disciplined man giving momentary release to his grief and rage.

When Lee sets the hotel on fire to flush out Morgan, the marshal handcuffs himself to Rick and leads him down the burning stairs and outside to the street, the shotgun pressed against the young man's jaw. It's the iconic image of Sturges' film, a spectacle tipped on the edge of bloody, explosive violence that he holds for long moments as Morgan and his captive climb aboard a wagon and ride slowly, standing in tableaux, through Gun Hill's streets while Belden, his men and the whole town march in procession behind them.

It has an almost religious aspect to it, which makes the spectacle even more perverse.

But the longer Sturges holds this moment the more awful the release needs to be when it comes. It's the kind of thing he would perfect in The Magnificent Seven, and which a filmmaker like Sam Peckinpah would inherit and explore to terrible ends in films like The Wild Bunch and Straw Dogs.

The catastrophe comes, as it so often does in a western, at the train station, where Lee's poor aim is no match for Morgan's unerring gun, leaving both young men dead and the marshal bereft, with rough justice cheating him of rule of law. This only leaves the two former friends, locked into the final, convulsive act of revenge, and Belden with his dying words warning his friend to take care of his boy: "Raise him good, Matt."

If you're like me you can't help but speculate what will happen to Gun Hill now that both the man who owned the town and his heir are dead. Who will take over? Beero? More likely the bank, as the frontier has reached the stage where capital is the only guarantee of stability until government is strong enough to function.

Some critics insist that Jones' Linda fixes the bereft Morgan with a look of reproach as his train slowly pulls out of town leaving bodies in his wake. Perhaps, but I don't see it, though perhaps she's like the town, suddenly overcome with the loss of both her tormentor and protector.

Or maybe she's imagining how this might have played out if she could have exchanged one friend with another – the strong man for the just one – and how that slim chance has now passed. (Though it didn't stop Barbara Stanwyck from leaving town with Barry Sullivan after he killed her no-good brother in Forty Guns.) It's an operatic moment, though, and a wholly satisfying ending that makes the film as good as the best of Sturges' films, and that's saying a lot.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.