The Japanese surprise attack on the US Navy at Pearl Harbor was a surprise not just because the Imperial Japanese Navy had planned and executed it almost flawlessly, but because almost no one thought it possible and those who did were ignored. Hindsight is, of course, perfect vision but it's hard not to read accounts of the lead-up to the attack and wonder at the coercive power of conventional wisdom.

The willful blindness was bolstered by millions of Americans who opposed joining the war raging across the other half of the globe. Whether they supported Charles Lindbergh's America First movement or not, they were willing to allow German U-boats to attack US warships like the USS Kearny and USS Reuben James (sunk on October 31, 1941) as part of the cost of neutrality.

If you cared to read carefully the news wasn't good, though. On the first of December 1941 there was a UPI story describing how the Japanese army was moving into Indochina while the IJN was sending its fleet toward Manila in "a horseshoe encirclement" of troops in the Philippines under the command of Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

But military analyst Dewitt MacKenzie was confident that defeats of Japan's ally Germany in Russia and North Africa and ongoing peace talks between Tokyo and Washington showed that "Tokyo is anxious to evade conflict with America." MacKenzie, who had worked for the Associated Press since World War One, was considered an unimpeachable expert, with a columns and articles carried in 800 newspapers.

He would continue to offer his opinions for the rest of the war that started for America six days later and until he retired from AP in 1951. There is no indication that his misreading of Tokyo's intentions affected his reputation.

For decades there have only been two certainties about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The first is that planning, audacity and luck conspired to make it a complete surprise and a demoralizing blow to America's ability to wage war right out of the gate. The second is that thanks to luck and the arrogance of Japan it was ultimately nowhere near as catastrophic as it seemed to either side on the morning of December 8th.

But nearly thirty years later, when 20th Century Fox released Tora! Tora! Tora!, an epic, big budget retelling of the attack, the question remained: How could this have happened?

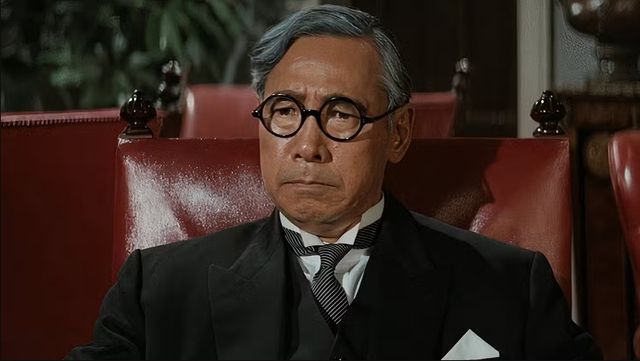

The movie begins not in Pearl Harbor but on the deck of the IJN battleship Nagato, where Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto (Sō Yamamura) is taking over as commander of the fleet. This massive set had been built when legendary director Akira Kurosawa was supposed to direct the Japanese sequences of the film, which would start with an elaborate "manning the rails" sequence that producer Elmo Williams had cut to a minimum when Kurosawa left the project just after filming started.

The Japanese crew are turned out immaculately, in vast numbers, and move with an almost machine-like efficiency. They are not, we are meant to understand, an enemy to be underestimated, though it was common to do just that in the US right up to and after the Pearl Harbor attack.

And Yamamoto is an impressive man, played by Yamamura (who had been introduced to American audiences in John Huston's 1958 The Barbarian and the Geisha, starring John Wayne) as disciplined and fiercely intelligent. He has made enemies of the army and has become a target for assassination, but he tells Yoshida (Junya Usami), the outgoing commander of the fleet, that he's "not that easy to kill."

After this things move fast, with Japan signing the tripartite pact with German and Italy. The action moves to Washington where we meet secretary of state Cordell Hull (George Macready) and secretary of war Henry Stimson (Joseph Cotten) and learn how America has responded to this and Japan's ongoing war with China by putting the country under an economic blockade.

From here the camera follows US army intelligence officer Lt. Col Rufus Bratton (E.G. Marshall) into Naval headquarters in Washington, where he meets with Lt. Commander Alwin Kramer (Wesley Addy), his opposite number there. They're in charge of "Magic", a codebreaking operation that's reading Japanese diplomatic cables, monitoring them for signs of ominous portents. These two men – executive level noncombatants, technocrats in uniform – are basically the film's protagonists.

It isn't until fifteen minutes into the picture that we arrive in Hawaii, where another new commanding officer – Admiral Husband Kimmel (Martin Balsam) is taking over, flying over the harbour in a PBY Catalina, pointing out the obvious deficiencies in the Pacific Fleet's new anchorage, where they'd moved to in 1940 from their base in San Diego. In adjacent scenes Kimmel and Yamamoto note that the British had made a successful attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto, modifying the torpedoes on their carrier-launched planes to overcome the shallow depth of a harbor very much like Pearl Harbor.

Kimmel meets with Admiral "Bull" Halsey (James Whitmore), commander of his aircraft carrier groups, and they complain how President Roosevelt's undeclared war on Germany is starving them of resources when they know that a war with Japan is imminent. And we meet Major General Walter Short (Jason Robards), the commander of the army in Hawaii, in charge of the defense of Hawaii. His concern is sabotage and the 130,000 Japanese-born or descended locals on the island. There is a powerful amount of exposition front-loaded into Tora! Tora! Tora! and for anyone with more than a passing familiarity with the story, it feels like having to hack through a lot of weeds.

Tora! Tora! Tora! began with Fox studio head Daryl F. Zanuck and his war epic The Longest Day (1962), a passion project that had also been a box office hit in a decade when Fox was harassed by a string of big budget flops. He wanted to make another picture about a key event in America's war and he turned to producer Elmo Williams, who had begun his career as an editor on films like High Noon and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and had worked on the production of The Longest Day and Cleopatra and survived both to remain in Zanuck's good books.

Much like The Longest Day, which had three directors to portray four different perspectives on the D-Day landings, Zanuck wanted to have an American and Japanese director for this picture. He chose Richard Fleischer for the American scenes, a veteran who had made everything from The Vikings and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea to Compulsion and The Boston Strangler. For the Japanese scenes he picked the most famous Japanese movie director in the world.

Williams and Kurosawa had agreed to tell the story of the Japanese attack as faithfully as possible, which was made easier as many of the key participants were still alive, like Minoru Genda, the planner of the Pearl Harbor operation (played by Tatsuya Mihashi). He had become a general and chief of staff in the Japan Air Self Defense Force after the war and had entered politics after retiring.

In All the Emperor's Men: Kurosawa's Pearl Harbor, Hiroshi Tasogawa tells the story of Genda taking the director to visit the Office of War History in Roppongi. "When Genda set foot in the room," he wrote, "the few people who noticed him first snapped to attention with military salutes. The salute then passed across the large office in a wave as every person stood to attention. Genda calmly returned the salute. From behind him, Kurosawa looked on, unsure how to act."

The director was also unsure how to act in a production where he wasn't completely in charge, and he began clashing with Williams, Zanuck and Zanuck's son Richard, who was chief executive at Fox and had taken a mutual dislike to Kurosawa, whose vision for the Japanese sequences of the picture saw the prospective budget balloon to $20 million. Pre-production dragged on for years, which included a hiatus as the studio experienced financial trouble thanks to the box office failure of pictures like Dr. Dolittle (directed by Fleischer) and the Julie Andrews vehicle Star!, which had hopefully re-teamed her with Sound of Music director Robert Wise.

Kurosawa left the picture after clashing with Richard Zanuck and exhibiting erratic behaviour that included seizures, which would later be diagnosed as epilepsy. Also departing the film was Toshiro Mifune, who agreed to play Yamamoto, but only as long as Kurosawa was directing. He was replaced by two directors, Toshio Masuda and Kinji Fukasaku, who were more willing to work as contract employees in a major Fox production.

While Bratton and Kramer try to divine Japanese intentions during long, unproductive diplomatic negotiations with the U.S. we watch as Yamamoto conceives of a plan to make a decisive strike against the U.S. Pacific fleet, gambling that it will cripple their ability to wage war and force them to sue for peace. He assigns the task of planning the attack to Genda, who chooses his friend, Lt. Commander Mitsuo Fuchida (Takahiro Tamura) to lead waves of planes from six aircraft carriers.

Tamura plays Fuchida as a stepping razor, imbued with the samurai spirit, and contrasts the excellent performance of his crews during training with the dismal attempts by American ones under Halsey's command. We witness ominous portents of communications failures and defensive blunders. General Short insists that all of his planes are grouped in the centre of his airfields, which will discourage sabotage from the ground but make them a convenient target from the air.

The army is unable to position their new radar installation in an optimal position thanks to a feud with the Hawaiian park service, the Ministry of the Interior and the island's wildlife preservation society. Once set up at Opana Point, it goes into operation without any radio or telephone line; the crew are told to hike a mile to the nearest service station and make a call from there if they see anything. Meanwhile in Washington Roosevelt is taken off the priority list for Magic intelligence after a top-secret report is found in a White House waste basket.

Nomura (Shōgo Shimada), the Japanese ambassador in Washington, is perceived as sent to buy time for the militarists running the government in Tokyo to get their attack and invasion plans ready. He's even assigned an assistant ambassador, Kurusu (Hisao Toake), whose previous job was to sign the Axis pact with Germany and Italy.

Yamamoto understands that an attack against the Americans is a gamble. But when diplomacy fails and the government under Hideki Tojo (Asao Uchida), in thrall to their expansionist plans in southeast Asia, gives his attack the green light, he dutifully takes his place at its command. The Kidō Butai sets sail from the Kuril Islands under radio silence.

In Washington Bratton is convinced that the Japanese are about to attack Pearl Harbor on a Sunday morning, but he raises the alarm a week early. A fourteen-part communique is sent to Nomura and Kramer heads out on the night of December 6th, chauffeured by his wife, to find an official on the list who will authorize sending a warning to Kimmel and Short in Hawaii.

He finds them in evening dress, attending parties, or out walking their dog. Nobody is willing to make a move until the final Japanese communique is sent, decoded and translated. When Bratton gets the final part he finds all the offices empty on a Sunday morning and Gen. George Marshall, the army chief of staff, out riding at Fort Myer. Admiral Stark (Edward Andrews), chief of naval operations, decides against warning Kimmel directly and decides to call Roosevelt instead. The army's radio network is experiencing atmospheric interference and, unwilling to send their warning via the Navy's network, they decide to send a message to Short by telegram.

Elmo Williams and the crew of Tora! Tora! Tora! quickly discovered that there were no airworthy Japanese planes they could use to film their waves of attackers at Pearl Harbor. But they discovered that the T-6 Texan trainer was a close match for the Zero, Japan's signature fighter, as well as the Nakajima "Kate" torpedo bomber, while Vultee BT-13 Valiants could be made to look like Aichi "Val" dive bombers.

The film would become one of the landmarks of practical filmmaking, with up to thirty planes in the air as Fuchida's strike force, while carrier take-offs from the Akagi, flagship of Vice Admiral Nagumo (Eijirō Tōno), commander of the Kidō Butai, were filmed on the USS Yorktown. A B-17 bomber, part of a luckless air group who flew right into the Japanese attack, duplicated the actual forced landing of a plane on only two wheels.

Along with spectacular second unit footage of the destruction of whole squadrons of replica P-40 fighters on the ground, it would be recycled in war movies for decades to come. There were, sadly, real fatalities during production of the film: Jack Canary, a veteran pilot and consultant on the picture, was killed in a crash while ferrying a Ryan PT-22 mocked up to resemble a "Kate", and a stunt pilot flying a "Val" replica was killed when his plane crashed into Pearl Harbor.

In the end the film took more time to plan and film and cost more money than the actual Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Faced with rising costs, Williams and Fox were forced to forego casting major stars and opted to fill their U.S. cast with a superb collection of character actors.

It was a decision that probably helped ensure the picture's lasting reputation. I remember watching Tora! Tora! Tora! for the first time on TV, one of those "major motion picture" prime time premieres advertised for weeks, and only faintly recognizing actors like Balsam, Whitmore, Andrews, Marshall and Robards. They might not have been stars, but they had gravitas, and it made me buy them as career military officers, caught up in major historical events.

Many of them, including Balsam, Whitmore, Addy and Andrews, were World War Two veterans. Robards was on the USS Northampton, which sailed into Pearl Harbor two days after the attack, where some of the battleships in the harbor were still on fire. He would survive the sinking of the Northampton at Guadalcanal.

After an intermission, the film finally arrives at the morning of December 7th, 1941. There's a brief moment of comic relief when Fuchida's attack wave meets a biplane from a flying school flown by instructor Cornelia Fort (the unjustly obscure Jeff Donnell), who takes in the warplanes suddenly all around her and executes a spectacular midair spin and dive to safety.

In real life Fort was flying an Interstate Cadet monoplane, flew straight into the Japanese attackers and was pursued by a Zero who strafed her on the runway when she landed with her student. Fort would join the Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS) when war broke out and was killed when the BT-13 she was flying from Long Beach to Dallas was hit by an army pilot in midair, sending her into a fatal dive.

Fuchida's force achieved total surprise thanks largely to failures in U.S. communication; the radar station at Opana Point, now with a telephone line but only operational for three hours that morning, spots the two massive waves of Japanese planes but a lackadaisical, cigarette smoking junior officer at the communications office dismisses the report by saying "Yeah? Don't worry about it."

Out at the mouth of the harbor the USS Ward spots and sinks a Japanese mini sub trying to sneak into the anchorage. When Lt. Harold Kaminski (Neville Brand), a duty officer at harbor defense, calls Capt. John Earle (Richard Anderson) with the report, he's told that the Ward's skipper is a "green kid", that they've had false reports like this, and that he should get back to him when has confirmation.

Later, when battleship row is on fire through the window of Kaminski's office, the lieutenant spits back at the captain what's probably the film's second most famous line: "You wanted confirmation, captain? Take a look. There's your confirmation!"

Kimmel has a golf date with Short when the attack begins; he watches his ships explode from his lawn in his navy whites while waiting for his driver. Short is waiting at the first tee when he sees and hears the first explosions. Two naval officers standing at attention during the morning flag raising watch a Japanese bomber fly overhead and one of them tells the other to get the plane's number so he can report the pilot for safety violations.

All through the attack we watch the telegram for Short make its way from desk to desk before being picked up by a young Japanese American courier. Kimmel watches the attack reach its crescendo with the catastrophic explosion of the USS Arizona when the warning finally reaches his office. In Washington Ambassador Nomura is late to his appointment with Cordell Hull thanks to lack of staff to decode and type up the communiques from Tokyo, and delivers the declaration of war nearly an hour after the Japanese attack had begun.

Back on his flagship Yamamoto receives the jubilant news of a successful surprise attack impassively, but only reacts when he's told of Nomura's tardiness. This sneak attack, he tells his staff, will only provoke the Americans. "I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve." Elmo Williams claimed that he had found the line in Yamamoto's diary, but was never able to provide proof, and though it perfectly expressed the admiral's opinion about the dismal odds of Japan defeating America, it remains the film's most notable departure from factual truth.

The film explains the reason for the Pearl Harbor disaster simply: the U.S. was a peacetime military up against a wartime enemy. But it's immensely sympathetic to Balsam's Kimmel, who is staring out his office window while his whole command burns and sinks when a spent round ricochets through the glass and bounces off the front of his navy whites. "It would have been merciful if it had killed me," he was heard to mutter.

The line sounds as overcooked as Yamamoto's but it was apparently real, and in any case Kimmel became the principal scapegoat when it was time to assign blame for the failure at Pearl Harbor. At the same time in the Philippines Douglas MacArthur was in charge when a Japanese surprise attack destroyed almost all his air force on the ground, but he was there to preside over the Japanese surrender on the deck of the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay nearly forty-four months later.

In 1942 the Roberts Commission found Kimmel and Short culpable in the failure to defend the Hawaiian Islands from Japanese attack; the Admiral retired from duty that year and died in 1968. Kimmel's family are still fighting to clear his name. Even Rufus Bratton found himself tarred by the debacle despite all his efforts to broadcast warnings of the attack. He served as General Patton's intelligence officer in the Third Army in Europe, and despite repeated efforts Patton was never able to get Bratton promoted to brigadier general.

Tora! Tora! Tora! was a disappointment to Fox in North America but was a major hit in Japan, where Masuda and Fukasaku's (and Kurosawa's) depiction of Yamamoto and the men of the Kidō Butai were judged to be portrayed with appropriate dignity and respect.

It was not a critical success at the time, however, and Roger Ebert famously gave it a single star in his Chicago Sun-Times review, calling it "one of the deadest, dullest blockbusters ever made." Ebert would, however, give Michael Bay's execrable 2001 film Pearl Harbor an extra half star. But its appeal with audiences continued to grow and today Nick Hodges, a YouTuber who reviews films for historical accuracy, considers it a classic on the level of Sergei Bondarchuk's Waterloo (1970).

Universal would try to ride on the abiding appeal of Tora! Tora! Tora! in 1976 with their star-studded Midway, featuring Henry Fonda, Charlton Heston, James Coburn, Robert Mitchum – and Toshiro Mifune as Yamamoto. The less said about this film and its mawkish violation of historical fact the better; thankfully a much more satisfying take on the Midway story would be made in 2019 by the wholly unlikely Roland Emmerich.

Admiral Yamamoto did turn out to be a hard man to kill, but the U.S. Army Air Force managed it in April of 1943, after breaking Magic codes and ambushing his plane with a squadron of P-38 Lightnings. Eighty-three years after the attack, there are apparently just sixteen living veterans of Pearl Harbor and Lou Conter, the last survivor of the USS Arizona, passed away in April of this year.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.