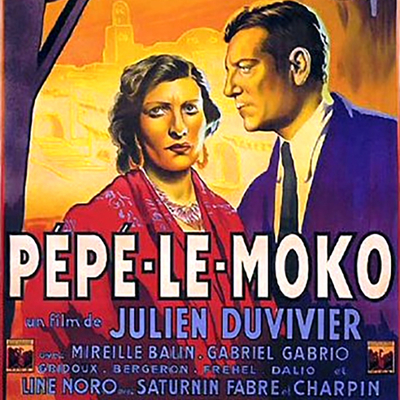

An important film's cultural influence can spread in any direction. Julien Duvivier's Pépé le Moko (1937) is one of a small group of films regarded as essential in what would later be called film noir, for instance. But it also played a major part in the creation of a certain cartoon skunk who would become beloved in the Looney Tunes stable of characters – before that cartoon critter was canceled at the height of the lockdown cultural purges, of course.

When Mel Blanc created the voice of Pepé le Pew for the 1945 cartoon Odor-able Kitty (though he was called Henri for the character's debut), he drew on Charles Boyer's performance in Algiers (1938), a remake of Duvivier's film with Boyer playing the role that Jean Gabin had made famous a year earlier when Duvivier's film was an international hit.

While neither Boyer nor Gabain ever uttered the line "Come with me to the Casbah" it was shorthand in parodies of Boyer and Algiers and became a trademark for Blanc's Pépé, and inspired the title of a 1954 Looney Tune, The Cats Bah, featuring the skunk, whose bachelor pad is shown adjacent to that of Pépé le Moko in Algiers. In time the character would outlive all of the cultural references that audiences shared for years after his creation.

In real life Gabin and Boyer had a rivalry that turned sour when the two worked in Hollywood during the war and Boyer spread rumours about Gabin collaborating with the Vichy French. Gabin had, in fact, agreed to work on Vichy propaganda while biding his time waiting to get out of the country. (Ask yourself what you would do to escape Occupied Europe during World War Two.)

But Gabin silenced Boyer's allegations when he offered Boyer the chance to settle things by stepping outside. And after making just two movies in America Gabin returned to fight for the Free French forces, commanding a tank in North Africa and Europe and winning the Military Medal and the Croix de Guerre.

But this was still years in the future when the title credits rolled on Pépé le Moko, the call to prayer giving way to a jazzy Latin number before the first scene begins, in the offices of the Algerian police. A delegation of Parisian cops are putting pressure on the local gendarmerie to make good on the arrest warrant for Pépé, a renowned gangster and thief who has been holed up in the no-go zone of the Casbah for two years.

The local police describe the Casbah as a "labyrinth...slimy...dark...dank and lice-infested." But the Parisians want to go in with force and flush Pépé out. They can try, says Inspector Slimane (Lucas Gridoux), but they'll get nowhere; he prefers his own plan – a strategy of making himself familiar in the Casbah, even befriending Pépé, discovering his weakness and playing a long game.

Meanwhile in the Casbah Pépé's gang is assessing the value of their latest jewel heist with Grand Pere (Saturnin Fabre), their resident fence. The hot-headed Carlos (Gabriel Gabrio) wants to sell quickly, much as he wants to do everything, while Pépé prefers biding his time. While they argue a contingent of slumming tourists get caught up in the police raid outside and the beautiful Gaby (Mireille Balin) is separated from her friends and ends up taking refuge downstairs in a cafe while Pépé's gang take pot shots at the police from the roof upstairs.

In a series of closeups Pépé takes in Gaby's jewelry before their eyes meet; she's fascinated, he's smitten, and Slimane is there to observe it all. The criminal and the cop are on such intimate terms that Pépé lets Slimane go through his pockets for cigarettes while he has a bullet graze on his arm bandaged. They obviously respect each other immensely, even share an affection, but the policeman tells the thief that he has the date he'll arrest Pepe written on his wall, in a spot where the sun hits it every morning.

Gridoux plays Slimane as lizard-like, with an insinuating voice and manner – just one of the excellent performances in Duvivier's film, which is stylized and often dream-like. Pépé's gang includes Jimmy (Gaston Modot), a sinister dandy who spends much of the film playing with a cup-and-ball, and Max (Roger Legris), who takes in everything with an even more unsettling simple-minded smile.

And then there's Pépé's favorite, Pierrot (Gilbert Gil), a young deserter from Normandy who has made the mistake of befriending the oily, unctuous Regis (Fernand Charpin), an obvious police informant who has wormed his way into the periphery of Pepe's gang, and the confidence of his Arab girlfriend Ines (Line Noro). Pepe is beloved in the ancient, anarchic Casbah, though there are still threats everywhere.

Into this walks Gaby, the mistress of a rich, corpulent older man who made his fortune in champagne. She can't be sure if Pépé's interest in her doesn't begin with her jewels, but he's far more exciting than anything her status as kept woman is providing. They discover that they grew up in the same part of Paris; Pépé has grown tired of the Casbah and his lack of real freedom and is nostalgic for home.

"With you, I escape," he tells Gaby. "You're a different landscape." His interest in her evolves into that most French of love stories – an amour fou – as the noose around him in the Casbah is gradually tightened by Slimane and the police.

Gabin was a Parisian, the son of a cabaret entertainer who took his father's stage name when he began his career after he finished his military service. When the French film industry made the transition to talkies his resonant voice made him a natural, with his first acclaimed performance as a star in Duvivier's film of Maria Chapdelaine (1934), playing a Frenchman who becomes a fur trapper in Quebec. Duvivier cast him as a French Foreign Legionnaire in La Bandera (1935), set in the Spanish Civil War, and he would play Pépé le Moko the same year as his other big star turn, as the working-class officer in Jean Renoir's La Grande Illusion. Gabin's story is very French, or of a very particularly French kind of stardom.

He worked with Renoir again on La Bête Humaine and with Marcel Carné in Port of Shadows, both in 1938 and both classics made during a golden period in French cinema. He was offered to move to Hollywood following actors like Boyer, but he refused saying he "didn't travel well." The outbreak of war and German occupation made him change his mind, and he ended up making two films in America – The Impostor, a war drama directed by Duvivier (1944), and Moontide (1942).

Both films were flops, but Moontide was the more interesting of the two. Originally meant to be directed by Fritz Lang, this Mark Hellinger-produced picture was taken over by Archie Mayo (Charley's Aunt, Orchestra Wives, Crash Dive) and teamed Gabin with Ida Lupino and Claude Rains. He plays Bobo, a drifter sailor with a drinking problem and a bad temper who falls in with the suicidal Anna (Lupino).

It's a desultory kind of thriller that takes place on the wrong side of the tracks (or the harbour, as it were), made as part of the same move toward "poetic realism" as Pépé le Moko – a largely French genre that echoed in Hollywood in films as different as those made by John Ford (The Long Voyage Home) and Frank Borzage (History is Made at Night). But there's no denying that Gabin seems out of place in Moontide – his acting style comes from a different place than anyone else in the picture; it's as if he knows something they don't.

Gabin is frequently compared to Humphrey Bogart, and the actors are imagined as embodying a certain image of stoic masculinity, cynical but with a guarded romanticism that can be drawn out by the right woman or cause. But Gabin's persona was perfectly refined when Bogart was still playing mere gangsters in pictures like Dead End (1937), Angels with Dirty Faces (1938) and The Roaring Twenties (1939).

It wouldn't be until 1941 and films like High Sierra and especially The Maltese Falcon that Bogart's own persona would become codified and marketable, and there has always been speculation that the American must have found some inspiration in the Frenchman who was making a big splash across the ocean and in a different language.

Though Gabin once told a story about being on a troop ship caught in a storm on his way to fight for de Gaulle. Frightened, he said he cowered by a railing until he remembered seeing a picture with Bogart on a ship (perhaps Across the Pacific or Action in the North Atlantic) and decided to present a brave face and copy Bogart.

In the Casbah, the police try to bait a trap for Pépé; Regis says they should use Pierrot, and that he'll forge a letter from the young man's mother saying that she's made her way to Algiers and is staying outside the Casbah. He has the letter delivered by L'Arbi, another snitch, played by Marcel Dalio, who would star in Renoir's Rules of the Game before leaving for Hollywood and roles in films like Casablanca.

But the plan backfires and Pépé's gang take Regis prisoner, sweating him while they wait for Pierrot to return. The informant comes apart while they make him play endless card games; the young man returns after escaping from custody, mortally wounded, and Regis cowers in a corner but Pierrot dies before he can get his revenge.

It's a tense, unbearable scene that ends with real cruelty as Regis is shot over and over by Pépé while he begs for mercy on the floor. The cruelty of this scene is just one of several dropped or soft-pedaled in Algiers, director John Cromwell's nearly shot-for-shot remake of Pépé le Moko, which included Gaby being a kept woman and Pépé's tragic ending.

Slimane has an altogether more subtle trap in mind, using Gaby to lure Pépé out of the Casbah. He nearly succeeds the first time, but Ines successfully deceives a drunken Pépé into returning to his apartment to wait for Gaby. His manic ardour briefly cooled, he thanks her for bringing him to his senses.

There's a lovely scene in the film where Pépé sits waiting for Gaby with Tania, the girlfriend who Carlos regularly beats. She's played by Fréhel, a singer who specialized in the melancholy bal musette, whose career began before World War One. As a teenager she had an affair with Maurice Chevalier; when he left her she attempted suicide. She moved to the Balkans and Russia, became an alcoholic and a drug addict, and returned to France where, as it happens, she became a star.

Fréhel often played singers in films, and as Tania she tells Pépé how she likes to console herself by singing along to one of her old records and looking at pictures of herself when she was young and beautiful. She puts on "Où est-il donc", a song about missing a Paris that has long since disappeared; it's a heartbreaking moment that does so much to sell Pepe's fatal nostalgia for home.

Slimane is persistent, and orchestrates an even more byzantine plan using Carlos and Gaby's champagne merchant, which finally draws Pépé out to the harbour with a ticket on the same ship back to France as Gaby. But Slimane is waiting and takes Pépé into custody just seconds and inches from reuniting with Gaby.

The policeman's waiting game has worked, and for a moment he thinks he's won what he hoped would be a bloodless hunt. But Pépé asks one last favour from his friend and stands at the closed gate of the dock, calling out Gaby's name, though he's drowned out by the ship's horn. He pulls out a knife and kills himself; suicide was, of course, anathema to the Hollywood Production Code, so Boyer's Pépé in Algiers would die like any self-respecting gangster in a hail of police bullets.

Gabin would have a hard time restarting his career after he returned to France after the war. He didn't really regain his footing until he played Max, an aging gangster in Jacques Becker's Touchez pas au grisbi (Don't Touch the Loot) in 1954. Cool and fatalistic, he reminded the French public just why he had been such a star, and the picture would start a comeback in the face of the surging nouvelle vague of Godard, Truffaut and Chabrol, who made a big show of rejecting the kinds of films and directors Gabin preferred.

From this point on Gabin had the status of a living legend; imagine if Bogart had lived for another twenty years instead of dying in 1957; it's easy to imagine all the young directors and actors who would clamour to work with him, and that perhaps even a few of those films might have been worth watching. Gabin would co-star with Jean-Paul Belmondo in A Monkey in Winter (1962) and with Alain Delon in several films including The Sicilian Clan (1969) and Two Men in Town (1973).

He would even face down the weaponized wantonness of Brigitte Bardot with a stony face in Love is my Profession (1958) – though this would not save him from succumbing to her in the end. Gabin would die of leukemia in 1976, and his ashes were scattered at sea. His co-star in Pépé le Moko, Mireille Balin, would have a much less happy end. Like Gabin she answered the call to Hollywood, arriving before him in 1937 with a staff of servants and twenty-eight trunks, though unlike Gabin she didn't make a single picture there.

Balin returned to France just in time for the occupation, however, and became a star in Parisian high society, falling in love with Aloïs Deissböck, a Wehrmacht officer. During the Allied liberation she tried to escape with him but was arrested at the Italian border; Deissböck's fate is unknown – he was likely executed without ceremony – but Balin was raped and beaten and sent to prison in Nice.

She was released on bail and forbidden to work, but when the ban was lifted she made one last film in 1947; her health broken, she died a pauper in a charity home in 1968. Another particularly French story.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.