On the 12th of April, 1975, the U.S. military put Operation Eagle Pull into effect, evacuating Americans and staff of the American embassy in Phnom Penh as well as Cambodians and third-party nationals by helicopter. Five days later the Khmer Rouge entered the capital, executed the members of the Cambodian government who remained behind and started evicting the population of the city, which included hundreds of thousands of refugees, to the countryside. Cambodia disappeared under a black cloud from which it would not reemerge until the end of the decade.

On January 10th, 2004 the actor and writer Spalding Gray took his children to see Big Fish, Tim Burton's film about a dying man notorious for his fantastic, improbable stories. That evening Gray said he was going out to meet a friend but left his wallet behind. He was last seen boarding the Staten Island Ferry; two months later his body was found in the East River.

On the surface there doesn't seem to be much connecting the two events. Anywhere from 1.5 to 2 million people were killed in the genocide begun on the afternoon of April 17, 1975 by the Khmer Rouge and its leader Pol Pot. The only victim of Spalding Gray's last trip on the Staten Island Ferry was himself, at the end of a deep depression that had overcome him just over two years earlier, when he was involved in a car accident on a road in rural Ireland.

In 1983 Spalding Gray was cast in Roland Joffe's film The Killing Fields, which tells the story of Sydney Schanberg, a New York Times reporter caught up in the Khmer Rouge storming of Phnom Penh and his attempts to discover the fate of his Cambodian photographer, Dith Pran, under Pol Pot's regime. Gray was working with a cast that included Sam Waterston, Julian Sands, John Malkovich, Craig T. Nelson and South African playwright Athol Fugard, but his character is simply called "U.S. Consul".

Joffe's film was a critical and box office hit, and was nominated for seven Academy Awards, winning three. When he returned to New York City Spalding Gray began writing a theatrical monologue based on his experiences on the set in Thailand, which would turn into an improvised performance piece that ran for as long as four hours. By the time director Jonathan Demme began making a movie version of Swimming to Cambodia it had shrunk to around two hours, and onscreen Demme and editor Carol Littleton trimmed it to an economical 85 minutes.

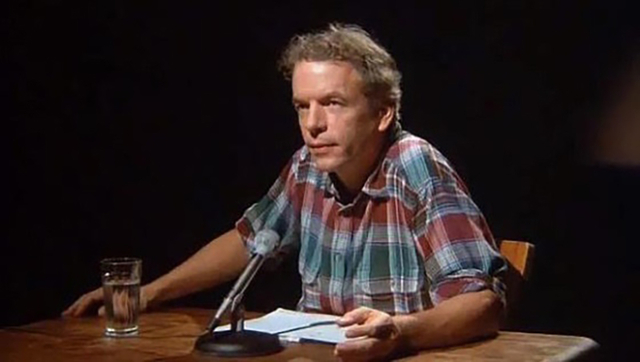

The film begins with a rumpled-looking Gray walking through the streets of SoHo before entering the unassuming front door of the Performing Garage, home of the Wooster Group, the off-off Broadway theatre company that launched the career of Gray as well as Willem Dafoe, Ron Vawter and Kate Valk. We see him walk past the audience in the bleachers and take his place behind a wooden desk on the stage. He pulls out a McDonalds notebook, adjusts his microphone, takes a sip of water from a glass on the table and begins to talk.

He sets the scene: it's a day off during the shooting of The Killing Fields and the cast and crew are relaxing at their hotel on the Gulf of Siam – a facility Gray compares to "a very modern prison, something like the prisons or, uh, private prisons people are investing in here in the United States instead of hotels, something like a pleasure prison."

He describes Joffe's British crew as a louche, hard-living, more than faintly piratical bunch. They refer to all the actors, regardless of their billing, as "artists" – Gray finds this immensely flattering – and the first thing the film's electricians do upon arrival in Bangkok is buy girls; a pair in case one gets bored and wanders off. He's fallen in with the head of the second camera unit, Ivan Strasburg, a South African who is the "devil in my ear... a bit of a Mephistopheles figure, gray beard, handsome man" and the source of much of Gray's temptation to act recklessly.

His girlfriend Renee has arrived from America for a visit, but Gray is caught up in the adventure of filming in this exotic locale and wants to stay until he's achieved his "Perfect Moment" – a kind of provisional epiphany towards which he's always striving. Renee has given him an ultimatum: either marry her or give her a date when he'll return to New York City. Spalding names an arbitrary date – July 8th – and is free to go in search of his Perfect Moment.

Spalding Gray was born in Rhode Island, a middle son raised in rectitude and fastidious WASP prosperity to a corporate executive father and a Christian Scientist mother. Countercultural currents took him west, to the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, where he taught poetry. His mother's suicide brought him back east, where he settled in New York and began an acting career.

While taking roles in porn films he also helped found what would become the Wooster Group with his girlfriend Elizabeth LeCompte as its artistic director. A trilogy of plays about his mother and his childhood led Gray to writing and performing theatrical monologues about his life, reviving a genre that had its roots in America with Mark Twain.

By the time he made Swimming to Cambodia, which was produced by his girlfriend (and later wife) Renee Shafransky, he had developed an onstage persona that reflected himself at least in parts: a WASP afflicted with Jewish neuroses, anxiety-ridden, hypochondriacal and prey to poor impulse control, spiritually questing but prone to belief in any sort of dharmic quackery.

On location in Thailand and in search of his Perfect Moment, he imagines himself in his own words as "a kind of wandering bachelor mendicant poet, wandering the beaches of Malaysia eating magic mushrooms all the way until I reached Bali and evaporated in a state of ecstasy in the sunset."

Gray's memoir of his time on Joffe's set is full of digressions, like the one where he takes the train to Chicago and meets a Navy man – he calls him Jack Daniels – who talks about his preference for threesomes with married couples, his own loveless marriage, and his service career, which has taken him from Guantanamo Bay to hovering over the launch button in a "waterproof chamber" on a nuclear submarine, stoked with blue flake cocaine and ready to send his payload across the globe to Russia. (This was, of course, the '80s, and the Cold War would nudge its way into everything, for audiences primed to believe anything.)

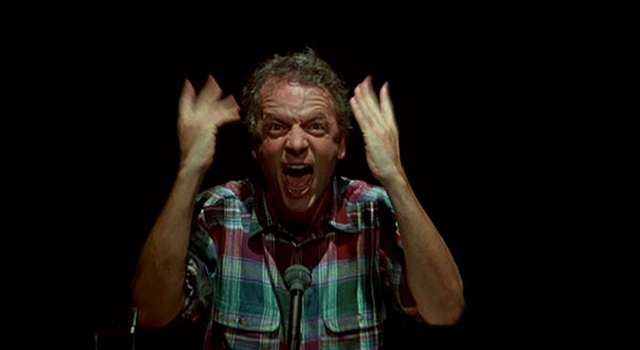

He describes sex tourism in Thailand, the services on offer in the massage parlours of the Patpong, Bangkok's red light district, and the things you'll see onstage at the bars and clubs amidst the brothels, where ping pong balls, full bottles of Coca-Cola and fruit are sprayed and shot from intimate places, and "a very ripe banana" is launched at the audience and "almost hits me in the eye, almost hits an Australian housewife in the head, hits the back wall and sticks! And slowly it inches its way down until it - Plump! - lands and is devoured instantly by an army of giant roaches."

It's a hellish, hilarious vignette, but Gray foregrounds it earlier in the film by warning us that the only thing that's not true in everything he's telling us is that the banana does not stick to the wall.

Gray is obliged to explain the political context of Joffe's film, one that he says he knew nothing about when he met the director and became determined to land a role in the picture, despite admitting that he had never voted. Using a pair of maps hanging behind his desk, just in front of the rear projection of a beach, Gray adopts the tone of a hip private school history teacher and delivers a concise precis of Cambodia's history, and how the war in Vietnam next door turned it from paradise into hell.

On the side of the good guys are the Cambodian people, whose easygoing, benign nature made Thailand look like a Nordic country, as Gray puts it. Their leader is "happy, sexy, sax-playing" Prince Sihanouk, who is overthrown in a coup by Lon Nol, a politician Gray hints broadly was a CIA asset. "No one in America knew anything about Lon Nol," Gray tells us. "The press didn't know anything about Lon Nol except 'Lon Nol' spelled backwards spelled 'Lon Nol'."

The new government allows the U.S. to send troops over the border to attack military installations Sihanouk had permitted North Vietnam to set up in Cambodia, which leads to Operation Menu, the bombing of Cambodia by American B-52s. This also begins North Vietnamese aid to the Khmer Rouge, who Gray describes as a redneck army led by Pol Pot, an ideologue educated in France "in strict Maoist doctrine with a touch of Rousseau."

Which brings us to Gray's big scene in The Killing Fields. His unnamed diplomat meets with Waterston's Schanberg and tells him about a targeting error – a B-52 that accidentally dropped its whole bomb load on a village with a homing beacon. It's a collection of screen-friendly diplomatic and military jargon that Gray has a hard time motivating himself to pronounce until he can conjure up visual metaphors in his own head for every phrase.

He hilariously goes through his thought process and recalls Joffe having to do dozens of takes before he manages to make it through his lines. He describes his terror at having to ride in a helicopter for the evacuation scene and falling for the lie that the choppers would only hover ten or twenty feet above the ground, but they take him far into the air where he can see Thai peasants piling car tires onto bonfires to generate smoke to make it all look like a war.

Less comic is his description of what the Khmer Rouge did when they won the civil war, emptying the cities to force the urban population to work the fields. Pol Pot, seeking to create a perfect Maoist utopia, was determined to skip through socialism entirely and purge the population of any potential reactionary elements. After executing government and military leaders, the Khmer Rouge targeted professionals and intellectuals: anyone who could speak foreign languages or even wore glasses was killed.

Pol Pot's version of Marxism was so extreme that he lost the support of China and even North Korea, and it threatened the stability of the region so badly that in 1979 his former supporters in Vietnam invaded and sent the Khmer Rouge back into the jungle, where they would split into factions and fight a guerilla insurgency until a negotiated truce brought Prince Sihanouk back to Cambodia in 1991.

You can tell that Spalding is honoured to have even a small part in telling the story of this monstrous crime against humanity – a genocide that went on almost invisibly until the Vietnamese invasion revealed the scale of the slaughter, unimaginable even when Paul McCartney and Kurt Waldheim organized that Live Aid precursor, the Concerts for Kampuchea, at the end of 1979.

But how well do we remember the Cambodian genocide today? Like most worthy Oscar movies, Joffe's film is more remembered than watched; Swimming to Cambodia might be a more effective reminder today than the film that inspired Gray's monologue. Even Operation Eagle Pull was overshadowed by Operation Frequent Wind and the evacuation of Saigon just seventeen days later, which produced that iconic image of the chopper on the roof of the U.S. embassy.

A few years ago the son of a friend told me about his recent vacation in Cambodia. A bright, sensitive young man, he had been invited by friends on holiday to Thailand, but decided he wanted to travel on his own while he was there; Cambodia was right next door, and a cheap trip, but he came back troubled by it all. There was just something odd about the country, he told me, something unsettling he couldn't put his finger on.

It might have something to do with the genocide, I said. You know – the nearly two million people killed in less than five years. He was surprised; he hadn't heard anything about it. I wondered about this young person traveling to a strange country without doing any research, not even a quick Wikipedia read.

There was even a movie about it, I told him. The Killing Fields? He'd never heard of it.

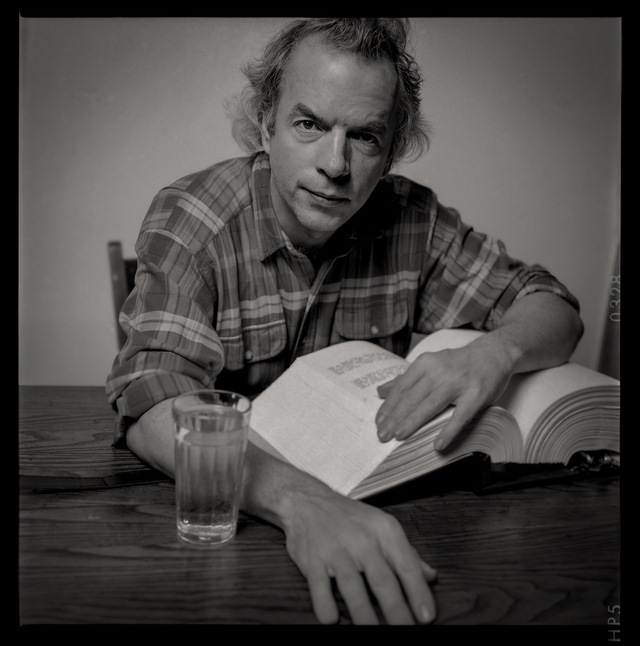

Spalding Gray, New York City 1990, photo by Rick McGinnis |

In February of 1990 I was sent to New York to photograph Spalding Gray in his SoHo loft. He had a new show, Monster in a Box, about his unsuccessful attempts to write a novel, Impossible Vacation, about his unsuccessful attempts to take a vacation, which began with the trip to Mexico City where he learned about his mother's suicide. I was met at the door by Renee Shafransky, who had been mentioned so often by Spalding in his monologues that she was something of a celebrity on her own.

She had to wake Spalding up, and after reminding him why I was there, patting down his bedhead and telling him to eat something before we took any photos, Renee left. I sat at a big table in Spalding's kitchen where we ate bread and cheese and talked about our mother's deaths. (My mother had died barely two years before and I still felt guilty and bereft. Spalding talked about his mother as if she'd also died recently; I'd learn later that it was over twenty years before I took my photos.)

I met Spalding again a couple of months later when he brought Monster in a Box to Toronto. When I saw him emerge into the lobby sheepishly from a door backstage, I went over to say hello. He said he remembered me and asked what I thought of the show. I said it was fantastic, and that I loved his performance. Immediately I knew I'd said something wrong.

"Was it a performance?" he said, panic rising in his voice. "Did it seem like a performance to you?"

Fortunately a group of his friends swooped down and whisked him away. I was mortified, but as someone who has suffered with depression most of my life, I'd recognized it in Spalding when we'd talked in his loft that weekend morning. I would never meet Spalding Gray again, but I never lost my concern for him, which came back with a shudder twenty years ago when I read the stories about his disappearance.

In the end Spalding gets his Perfect Moment, out in the Gulf of Thailand way past the more experienced and fearless Ivan Strasburg: a death-defying test of his swimming abilities which proclaims, in the movie that introduced Spalding Gray to a wider audience, the man's fascination with, and devout correlation of, water with death.

Swimming to Cambodia would launch Gray into the mainstream and create a market for his monologues that was still thriving when he died. A year later HBO would air Terrors of Pleasure, the story of his attempt to buy a house in the country, and Nick Broomfield (Kurt & Courtney, Heidi Fleiss: Hollywood Madam) made a movie out of Monster in a Box. Steven Soderbergh directed the film of Gray's Anatomy in 1996, where Gray threw himself into dubious alternative medicine to treat an eye condition.

Gray would continue to get roles in movies, but nothing he did (Beaches, The Paper, Beyond Rangoon, Diabolique, Kate & Leopold) approached the quality or prestige of The Killing Fields or his own filmed monologues. He would appear in Will & Grace and in nine episodes of The Nanny and get name checked on The Simpsons.

Gray would marry Renee Shafransky in 1991 and divorce her in 1993. He married Kathleen Russo in 1994 and began a family, which inspired the monologues It's a Slippery Slope (1997) and Morning, Noon and Night (1999). In 2001 he traveled to Ireland with his wife and several friends to celebrate his 60th birthday; they collided with a veterinarian's van on a dark road and Gray suffered a broken hip and a head trauma that was left untreated for a week.

The head wound caused neurological damage to his frontal lobe that intensified Gray's nascent bipolar symptoms and depression to the point where he could barely communicate. He began regularly writing suicide notes and rehearsing suicide attempts, inevitably on or near water. He sought treatment with famed neurologist Oliver Sacks.

"I was at pains to say that he could be much more creative alive than dead," Sacks wrote later, but admitted after several consultations with an increasingly spiritless Gray that "while I expressed hope and optimism outwardly, I now shared his doubt."

In The Anniversary, a short piece he performed near the end of his life, Gray wrote how he thought "about how I could not imagine living without my children, and how I would either have to die or learn to live without them. I thought about my mother and how she couldn't live without us, and how she took the more extreme way out." I can't help but remember that the only thing Spalding and I talked about at his kitchen table over that bread and cheese was our mothers, and how despair can wash away every Perfect Moment.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.