Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy were at the pinnacle of their careers when they made Sons of the Desert in 1933, an efficient and economical comedy feature barely over 90 minutes long that's considered one of their best films, and whose title was adopted as the name of the pair's international fan club. Perhaps not coincidentally, the film was made at a crucial point in the history of both Hollywood and America, and in the personal lives of its stars.

Sons of the Desert is technically a "pre-Code" picture, made just before the full weight of enforcement of Will Hays' Code was given to the Production Code Administration under Joseph Breen. Next to the introduction of sound, it would be the most critical factor leading to Hollywood's golden age, and despite lip service from studio management would be slowly and relentlessly undermined until the Code was a tattered rag at the end of the '50s, waiting for a few intrepid producers and directors to bury its bones.

It was also made just as the Twenty-First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution went into effect, overturning the Eighteenth Amendment that brought Prohibition into force – an ambitious social experiment doomed to failure. Next to the 1929 stock market crash and the Great Depression, it was the most critical factor in creating the America that would enter World War Two and emerge into the postwar economic miracle.

But that's a lot of weight to put on a film about two of the most beloved idiots in movie history.

The film begins with the meeting of a fraternal order, the fez-wearing Sons of the Desert, clearly patterned after the Shriners. America was once full of these lodges and clubhouses, sworn to membership in everything from the Masons and the Knights of Columbus to the Shriners, Oddfellows, Foresters, Elks, Eagles, Moose, Red Men, Templars, Maccabees and many more. They are – if they're still around – a legacy of a more charitable, socially-connected, community- and civic-minded America mourned by Robert D. Putnam in his 2000 book Bowling Alone.

Hardy was a Mason, while Laurel was member of the Grand Order of Water Rats, a British fraternal order for entertainers and music hall performers. (It's still around, though its membership would evolve over time; leaders or "King Rats" have included drag performer Danny La Rue, guitarist Burt Weedon and Rick Wakeman, keyboardist for prog rock legends Yes, who was King Rat from 2014 to 2015.)

Stan and Ollie arrive late, disrupting the meeting and the solemn address of their Exalted Leader, who is imploring members to come together to face what he describes as the greatest challenge faced by the lodge in its history – the upcoming convention in Chicago. He makes the men swear an oath to attend the convention in full strength – an oath that Stan doesn't think he can fulfill, though Ollie browbeats him into compliance.

Stan is worried that his wife won't let him attend the convention. (He constantly refers to their "Exhausted Leader.") The blustering Hardy insists that he does what he wants despite what his wife thinks and urges Stan to follow his lead. The truth of the situation emerges when the men arrive home; they live in adjacent houses, of course, which prompts a long comic interlude involving doorbells, the men getting locked out, and Stan being apparently unable to remember which door is his.

Laurel and Hardy were embroiled in domestic strife when they made Sons of the Desert. Stan's marriage to his first wife, silent movie actress Lois Neilson, was on the rocks; he would ultimately have four wives – five if you count his two marriages to Virginia Rogers, six if you include his first, common-law partner Mae Dahlberg, who would return to sue Laurel during his first divorce from Rogers.

Hardy had three wives, and his marriage to his second, Myrtle Reeves, was in trouble during production on the picture. He had filed for divorce in June of 1933, citing her alcoholism and "mental cruelty"; Stan had been separated from his wife Lois since the previous year, and had begun an affair with Virginia Rogers, his next wife, during a boating trip to Catalina that spring. Hardy would briefly reconcile with Myrtle but both men would have their income at the peak of their careers tapped by alimony and child support payments.

"With all these shenanigans," writes Simon Louvish in Stan and Ollie: The Double Life of Laurel and Hardy, "it is amazing that Sons of the Desert emerged so fresh, so light-hearted, its marital plot a catharsis of the real-life pain that so directly affected its heroes." Marital woes and unreasonable wives were actually a staple of Laurel and Hardy comedies, and the plot of Sons of the Desert borrowed liberally from We Faw Down (1928), an early sound short, and from Be Big!, a 1930 three-reeler.

Oliver's wife Lottie, played by Mae Busch, a standby in the pair's films, is your classic domestic harridan, a demon hausfrau. Despite Ollie's insistence that he's "king of his castle", Lottie obviously runs the house, and has her patience constantly tested by Stan. When Laurel blurts out their promise to attend the convention, she puts her foot down: they're going to the mountains, a trip for which she has planned and shopped.

Stan's wife Betty (Dorothy Christie) is even more intimidating, an amazon who's out duck hunting when the boys arrive home, a dead shot with an icy glare and wickedly sharp shoulder pads. It goes without saying that she keeps meek, spineless Stan firmly under her thumb, and without hope that he'll ever get permission to go to the convention. Throughout the film the two men refer to their respective homes as belonging to either Lottie or Bettie, underlining an impression that they're barely more than tenants, cut-rate, disenfranchised bungalow Babbitts.

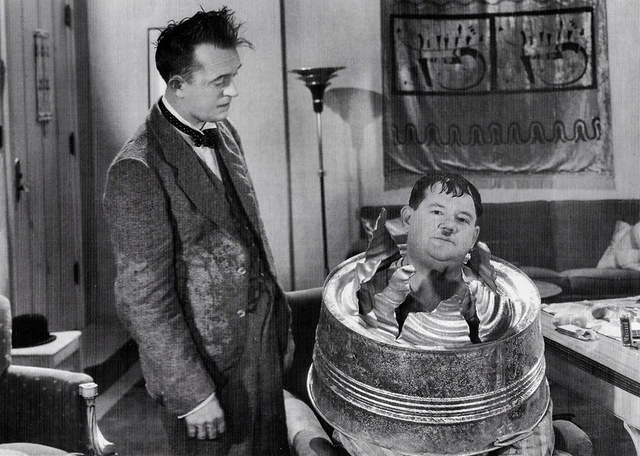

It isn't a Laurel and Hardy film without one of Ollie's desperate plots, and he enlists Stan to fetch a doctor who will attend to Hardy's sudden illness and prescribe a restorative trip to Honolulu. Stan delivers a veterinarian who makes Ollie swallow a massive pill, but not before Stan haplessly triggers a long slapstick routine that sees everyone end up in the big tin tub of hot water Ollie was using to soak his feet. But the subterfuge works, and Lottie insists not only that Ollie go to Hawaii, but that Stan accompany him.

Thus begins act two of the picture, with the boys on the loose in Chicago, parading through the streets with fellow delegates and living it up amidst nightlife that has been made wet again with the repeal of Prohibition. There's a montage of bars and booze – shots of barmen and bottles, trays of champagne and men gratefully quaffing huge steins of draught beer.

It's a bacchanalian celebration that the Code might normally have censored, but director William A Seiter and producer Max Roach banked on an explosion of elation as the Eighteenth Amendment was repealed on Dec. 5, 1933, and the new PCA under Breen not being quite up and running – a crack into which they could slip a salute to the return of legal inebriation and the defeat of temperance.

In what appears to be a former speakeasy (with its watchman still vetting visitors through a slot in the door) the boys enjoy the film's only production number – "Honolulu Baby" as sung by Ty Parvis, written by T. Marvin Hatley, the resident composer at Hal Roach Studios. Hatley, who had written "Dance of the Cuckoos", the ditty that became Laurel and Hardy's theme song, capitalized on the craze for Hawaiian music that began at the start of the '30s.

Hawaii had been a territory since 1898, but the rise of tourism and military installations on the islands made it both exotic and fashionable. Arrangements of island-themed numbers set to "hula" rhythms and scored with ukuleles and slide guitar, though only notionally based on traditional music of Hawaii and Polynesia, were constants on the hit parade, and make stars of Hawaiian musicians like Sol Ho'opi'i and provide hits for Bing Crosby.

"Honolulu Baby" would become a minor hit, and Hal Roach Studios would recycle it in Beginner's Luck, a 1935 short by the Little Rascals. Parvis is joined by chorus girls in glittery grass skirts and leis, and thanks to the generally second-rate production values of Roach Studios their shambling choreography (there's even an attempt at a Busby Berkeley-esque overhead shot) gives the number a suitably seedy ambiance that fits what we assume is the tone of this particular joint.

That lowered tone is helped immensely by another Roach star, Charley Chase, as a delegate from a Texas lodge who's hell-bent on being the life of this particular party. He's a practical joker, sneaking up on delegates who bend over to pick up the old reliable lost wallet to smack them with a bat, spritzing Ollie with a water-filled boutonniere.

A veteran of silent comedy who had come up through the Keystone and Mack Sennett studios, Chase was one of Roach's stars, though his turn as "Charley" in Sons of the Desert was a raucous departure from his usual comic persona. "The character was so obnoxious, and so at odds with the amiable clown he played in his own short pictures," writes Louvish, "that Charley was said to have prevented his teenage daughters from seeing the film at the time."

He tells Stan and Ollie that he has a sister in Los Angeles who he "hasn't seen since I was kicked out of reform school." He calls her from a phone he has brought to their table and puts Hardy on the line; they flirt and she gives him her address if he wants to drop by, but needless to say it's his wife Lottie. Like the world of the screwball comedy that would emerge with the enforcement of the Code, Laurel and Hardy's comic universe relies on everyone being more than a little bit morally unmoored.

When I was a boy and television networks still had a hard time filling daytime hours, Laurel and Hardy's Roach shorts would appear in the TV guide alongside other syndicated comedy franchises of the '30s and '40s – the Little Rascals and the Bowery Boys, Abbott and Costello and the Three Stooges.

The Marx Brothers had already ascended to a hallowed place thanks to their counterculture rediscovery in the '60s, but you would inevitably be called upon to declare allegiance in some schoolyard or rec room to one comedy team or another. I had friends who swore by the Three Stooges and I forgave them for it, and while Abbott and Costello had their moments (though too many involving unfrightening monsters from Universal's horror catalogue) my loyalty was won by Stan and Ollie early and abidingly.

Neither of the other comic teams brought the same pathos to their pictures. Ollie was a tragic blowhard, and Stan's onscreen persona could be charitably called an idiot savant, less so as developmentally handicapped. They tormented each other by being respectively feckless and hapless, and never made it to the last frame of a picture without some kind of catastrophic humiliation. But they seemed blessed with a kind of grace – an innocence and lack of criminal guile or quickness to violence that made them eternally endearing.

Late in Hardy's life the duo gave an interview to film historian David Robinson in Sight and Sound magazine, where they explained how they thought comedy worked. "The fun is in the story situations which make an audience sorry for the comedian," Hardy said. "A funny man has to make himself inferior..."

"Let a fellow try to outsmart his audience and he misses," said Laurel. "It's human nature to laugh at a bird who gets a bucket of paint smeared on his face even though it makes him miserable."

"A comedian has to knock dignity off the pedestal," said Hardy. "He has to look small – even I do by comparison. Lean or fat, short or tall, he has to be pitied to be laughed at."

After quoting this interview in his biography of the pair, Louvish writes that "we have become very wary of that emotion – pity, and old centrepiece of the idea of compassion which has been philosophized into an out-dated oblivion. We are not allowed to feel pity for our fellow humans, lest we be accused of feeling superior to them. In a world that worships equality – in theory, if not in practice – the object of pity now more often rejects it, demanding not an emotion, but the delivery of a material compact."

"Unlike priests, rabbis, mullahs, or any kind of pastor, the clowns offer no succour in certainty, no solution or balm in an afterlife. In the here and now, they offer themselves, as sacrificial spirits, as objects of that part of our compassion that can realize the common flaws in us all."

With the convention over the boys head back to their wives armed with props – pineapples and leis, and a ukulele with which Hardy accompanies himself singing "Honolulu Baby". What they don't know is that Ollie's plan – like all of Ollie's plans – has come undone, and the ship that was supposed to be taking them home has foundered in a typhoon.

Their wives rush to the ocean liner's offices before the boys make it home, though they discover the news of their liner sinking from a newspaper the women leave behind on the breakfast table of the Hardy house. Lottie and Betty return before they can think up a backup plan, and the boys are forced to hide in the common attic above their houses, intending to show up the next day with the story of their harrowing escape from watery death.

Their wives in the meantime have tried to console themselves by taking in a picture, and end up seeing a newsreel from the Chicago convention showing their husbands off the leash in their fez and sash, chasing women on the parade route and mugging for the camera. Back home they argue about which one will admit to the lie first, Stan's wife angrily accusing Ollie of being a bad influence.

In the attic the boys try to sleep on a metal box spring Ollie has hung from the rafters, but a suitably malicious lightning bolt from the storm outside seeks them out and electrifies their hammock. They shimmy down the downspout and into the inevitable rain barrel but get spotted by a beat cop and brought inside to confront their angry wives.

Oliver tries to brazen it out with his story about the sinking, incorporating Stan's ad-libs about missing the rescue and "ship-hiking" their way home ahead of the rest of the survivors. This is the last straw for their wives, who give them a final chance to come clean; ever the victim of his own misplaced confidence, Ollie persists in the lie, but Stan crumples into sobs under the steely gaze of his huntress wife.

Ollie waits in the living room while his wife begins piling up every dish and pot in the kitchen; next door Stan sits like a pasha in a silk gown while Betty stirs him a cocktail, more gratified by winning her argument with Lottie than bothered by his deception. Through the thin wall of their bungalow they hear the crockery hit Ollie, his trademark wail of pain rising in volume and pitch as the barrage continues for an improbably long time, shaking the common wall between their houses.

Sons of the Desert passed the scrutiny of the new Production Code Authority without much note, though Louvish notes that in Pennsylvania "they demanded elimination of the 'scene of Laurel slapping woman on posterior with wooden slapper.'" Protests from Canadian censors were stranger:

In British Columbia they didn't like Laurel's running pun on being like 'two peas in a pot'. (Ollie: "Pod! Po-dah!") In Quebec the censors demanded the elimination of 'all scenes of girls wiggling their hips while dancing wherever shown.'

This is ironic as la Belle Province, while still overseen by a government working in tandem with the Catholic church, had a reputation – in Montreal at least – for being the most fully "wide open" anywhere in Canada, with burlesque houses and liberal drinking laws that you'd struggle to find anywhere else in the country.

Sons of the Desert opened to good reviews and great box office, making the top ten list of film grosses in 1934. The pair, however, were still on the production treadmill at Hal Roach Studios, committed to a grueling schedule for relatively poor money, much of which would be consumed in divorce court. With their contracts coming up – separately – in the next few years, they had to come up with a plan to preserve their partnership and improve their earnings. Unfortunately, like their films, any plan wouldn't survive to the end of the last reel.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.