Flying has never been safer, but I still know people who have a ritual checklist to bolster their air travel luck or anaesthetize their anxiety with some combination of medicine (prescription or illicit), booze or government weed. And I'm sure we've all heard of that person who's sworn off air travel altogether and gets across countries or oceans as if it's still 1925 – if they travel at all.

This despite the odds – a recent MIT study puts the likelihood of being in an accident while traveling by air at around one in 13.7 million. And it keeps getting better: the odds were one in 7.9 million trips by plane in the early part of this century, and a dismal sounding one in 350,00 from 1968 to 1977, which happens to be the golden era of the disaster movie.

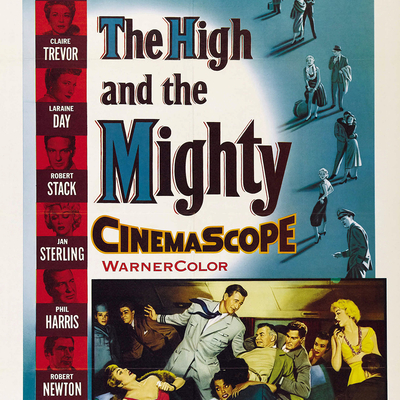

Before World War Two air travel was cold, loud, uncomfortable, inconvenient and expensive. Thanks to overclocked innovation in airplane design during the war commercial air travel by the early '50s was far more comfortable – on its way to being luxurious – and increasingly popular thanks to the proliferation of airlines and routes, though still expensive. But it wasn't strictly safe, especially if you count the number of accidents against the volume of travelers. This is the world in which William Wellman's The High and the Mighty is set.

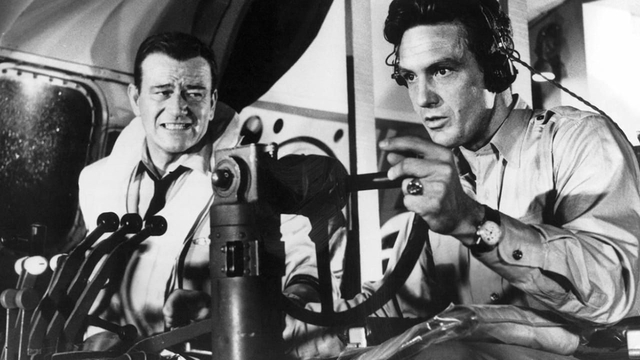

While Dimitri Tiomkin's justifiably famous score plays we watch a man in a pilot's uniform inspecting an airplane parked on the tarmac of an airport. And because the man is John Wayne we know we're looking at the movie's hero, all the more since the tune he's whistling is the melody of Tiomkin's theme.

As the music fades we head into a thicket of exposition. Dan Roman (Wayne) is a veteran pilot who's flying as co-pilot on a Douglas DC-4 from Honolulu to San Francisco. A talkative crew chief who knows him tells his ground crew that a few years ago Dan was in a horrible crash in South America when his plane was hit by wind shear on take-off and crashed, breaking in two in a fireball with his wife and son on board. The miracle, he says, isn't that Dan survived, but that he hasn't killed himself.

We meet the rest of Flight 420: Captain Sullivan (Robert Stack), navigator Lenny (Wally Brown) and Hobie the second officer (William Campbell). Dan and Lenny are old hands while Hobie is the kid and Sullivan has reached a critical but little-discussed point in his career where he's losing his nerve, sensing that his luck might have run out – like Dan's did in South America. Filling out the crew is Miss Spalding (Doe Avedon), the sole flight attendant.

While Spalding runs the check-in desk in the terminal – no TSA, no security screening or baggage checks and no barriers between the lounge and the tarmac; air travel as it was until the '70s – we get to meet the passengers. Ken Childs (David Brian) is a big deal on the island, a shareholder in the airline; May (Claire Trevor) is an ageing actress and good-time girl. Gustave Pardee (Robert Newton) is a famous Broadway producer traveling with his long-suffering wife Lillian (Julie Bishop). Sally McKee (Jan Sterling) is a former beauty queen joylessly following the trajectory of May but with less humour or charm.

Three couples comprise the film's commentary on various stages of marriage. There are the newlyweds Nell (Karen Sharpe) and Milo (John Smith), heading home from their honeymoon and unable to keep their hands off each other, and the overbearing, red-faced Ed Joseph (Phil Harris) and his wife (Ann Doran) – middle-class middle Americans who saved for years to afford their trip. And there's heiress Lydia Rice (Laraine Day) and her ne'er-do-well husband Howard (John Howard) who are heading home to a divorce.

Filling out the passenger list is Flaherty (Paul Kelly), an alcoholic physicist; Locota (John Qualen) a fisherman of indeterminate ethnicity; Briscoe (Paul Fix), who's dying of "holes in my bones"; Joy Kim (Dorothy Chen), a Korean refugee emigrating to the US and Toby, a little boy flying as an unaccompanied minor between his forlorn father in Hawaii and estranged mother in California (played by Michael Wellman, son of the director). Agnew (Sidney Blackmer) is the straggler, buying his ticket at the last minute, his sweaty demeanor spelling obvious trouble.

It's a bottom-heavy supporting cast who'll compete for our attention even in a film that's over two hours long, but it had dramatic precedent in pictures like Grand Hotel (1932) and would carry over into the big disaster movies of the '70s like Airport (1970), Earthquake (1974) and producer Irwin Allen's star-studded epics The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and The Towering Inferno (1974).

All these characters are there to provide emotional stakes; we'll root for a few and deputize others as villains – weaklings and cowards who jeopardize lives and make a bad situation worse. In Allen's films they'll provide tragic and heartbreaking deaths on the treacherous journey to rescue. But mostly they just provide melodramatic padding between catastrophes and action sequences.

Wayne and Doe Avedon's Spalding will help us figure out who we should favour; she takes a liking to Briscoe, an old charmer physically past the point of lechery, and Dorothy Chen's Miss Kim, who isn't given much to do in the script except apologize in her broken English for being dumb and ugly – the most cringeworthy thing in the script next to the overwrought newlyweds, who thankfully focus most of their treacly attention on each other.

Both Dan and Spalding take parental interest in Toby despite his annoying single bit of business – noisily running around the cabin with his balsa wood airplane. Thankfully Wellman wasn't too besotted with his son's performance to give him more screen time than he deserves, and Toby spends most of the film asleep on a pair of seats at the rear of the plane.

Typically tense and haunted, Stack's captain provides no real competition for Wayne as the picture's hero; Dan and Spalding are the only ones who notice the sudden jolts that shake the plane, and Dan can hear that one of the DC-4's four engines has an out of sync propeller. Dan, we learn, has experience as a pilot that goes back to open cockpit biplanes and the air mail; he flew a bomber in the raids over the Ploesti airfields and moved on to B-29s on Okinawa.

The only competition for alpha male in the cabin is the hearty, confident rich man Childs and the brusque, snobbish Pardee, who's afraid of flying and requests a chat with Capt. Sullivan, who reassures him that accidents are rare and that the plane's engines are more than sufficient to fly to San Francisco even if one or even two of them stop working after they pass the point of no return in the middle of the ocean.

After the thankless labour of drawing the characters and filling in exposition is done we reach the dramatic crux of Wellman's picture, right at that point of no return. It turns out that Agnew, who made his fortune with patent medicine, is a jealous man who accuses Childs of having an affair with his wife.

Those of us who've shuffled shoeless and beltless through airport scanners for twenty years will probably have noticed the toy six-shooter in its holster Toby happily carries on to the plane; it won't be a shock to see that Agnew has smuggled a revolver on board, and when he pulls it out to threaten Childs the plane lurches with a loud bang. One of the engines has failed, shedding its propeller blades and puncturing the fuel tanks on one wing.

A distress call is sent from the cockpit and the Coast Guard scrambles planes and boats. Wilby calculates that if they can get rid of excess weight, they might be able to make it to San Francisco despite the leaking fuel and the drag from the engine knocked askew when it failed. The passengers are enlisted in pulling their luggage from the hold and helping Dan toss it out of the plane; Claire Trevor's May is given a humorous moment to kiss her fur coat goodbye before she throws it out into the clouds.

John Wayne was not supposed to play Dan Roman in The High and the Mighty. He had just finished filming the western Hondo, which had the dual handicaps of being made in cumbersome (and gimmicky) dual strip 3-D and being released the same year as Shane. Hoping that big stars would help sell the clutter of subplots (a formula that would work for Irwin Allen) Wellman had approached Joan Crawford, Ida Lupino, Barbara Stanwyck, Ginger Rogers and Dorothy McGuire, who had all turned him down.

Spencer Tracy had agreed to play Dan – a handshake deal that Tracy pulled out of when friends had warned him what a taskmaster Wellman could be on set. With time ticking until filming started Wayne agreed to take the role, as his own production company was making it and time and money were at stake.

Wayne had started his production company with producer Robert Fellows two years earlier, and Wayne/Fellows had made Big Jim McLain, Plunder of the Sun, Island in the Sky and Hondo together, but The High and the Mighty would be the last film they'd make together. Fellows had begun an affair with one of their secretaries and, after disastrously asking Wayne to act as marriage counselor, he decided to liquidate his assets before the divorce settlement and got Wayne to buy him out.

The company would be re-named Batjac Productions and would exist until 1974, making pictures like Seven Men from Now, The Alamo, Cast a Giant Shadow, The Green Berets, Rio Lobo, Big Jake and Cahill U.S. Marshal as well as TV shows such as Swing Out, Sweet Land, a 1974 variety special about American manifest destiny, and an attempt to make a TV series out of the Hondo character that only lasted half a season on ABC.

The High and the Mighty reunited Wayne with Claire Trevor, his Stagecoach co-star, but they don't share much time onscreen. Trevor's brassy May ends up consoling Childs, whose confidence vanishes once everyone's life is in danger. To compensate for this Pardee, the fussy aesthete theatre producer who's terrified of flying ("Suppose two of your engines became uninterested in further toil?" he asks the pilot), described by his own wife as a "child man" who hates children, discovers inner strength he didn't imagine. He becomes a calming voice on the plane even though, as he admits to his wife, he's lying and is sure they're doomed.

A flashback reveals that Flaherty is also an artistic soul, a wannabe Gauguin who was enlisted in something like the Crossroads atomic tests at Bikini Atoll, the Ivy tests of the hydrogen bomb at Eniwetok and the Castle nuclear tests that took place just before The High and the Mighty was released, which exceeded projections massively, with drifting radiative fallout killing the radioman on a Japanese tuna boat. (A slender but palpable connection between Wellman's film and Gojira, the first Godzilla movie from Toho Studios.)

Sally the former beauty queen reveals to Flaherty that she's on her way to meet the man who wants to marry her, a handsome outdoorsman who fell in love with her picture in an old magazine, and that she's worried that eight rough years trading on her youthful looks have aged her beyond recognition. A brief mention by Miss Chen that she's an ethnic Korean born in Manchuria and a survivor of Japan's long, brutal occupation of the area hints at so much potential depth to her character, but neither Wellman nor screenwriter Ernest K. Gann make much of it. (Gann himself admitted that female characters weren't his strong suit.)

The newlyweds Nell and Milo remain cloying and winceworthy for the whole picture.

The unsung performance in Wellman's film is Doe Avedon as Spalding, who becomes our point of view character for most of the picture, interacting with everyone on the plane in ways that Wayne's Dan does not. A former model and the first wife of photographer Richard Avedon, the couple had been the inspiration for Fred Astaire and Audrey Hepburn's characters in Funny Face.

But she disliked modeling and turned to acting, divorcing Avedon and marrying actor Dan Matthews, who died in a car accident in 1952. Her film career was much shorter than her modeling colleague Suzy Parker but based on her performance as Spalding she might have had more potential. Avedon married director Don Siegel in 1957 and retired from movies and television a year later, only returning to the screen for a small role in John Cassavetes' Love Streams in 1984. She died in 2011.

Robert Stack as Sullivan the pilot doesn't have to do much more than brood for much of the picture, desperate to hide the anxiety that could cloud his judgment and cripple his career. It's something Stack could do well, and when he finally loses his nerve just before a potential safe landing and decides to ditch the plane, Wayne slaps him back to his senses and Stack thanks him for it; a slap from John Wayne, after all, is the cinematic equivalent of a knighthood or an epiphany.

Wayne was supposed to have hated his performance in The High and the Mighty but the film was a big hit, making $8.5 million on its $1.47 million budget. The picture received six Oscar nominations, including ones for Wellman, Claire Trevor and Jan Sterling, but Dimitri Tiomkin was the only winner for his classic score.

There had been pictures retroactively dubbed as disaster movies before, like San Francisco (1936), In Old Chicago (1937) and Carol Reed's The Stars Look Down (1939), but this peculiar genre only started taking shape in the '50s, with two Titanic films (the 1953 Fox production Titanic and 1958's A Night to Remember) and plane-in-peril pictures like Jet Storm and Jet Over the Atlantic (both 1959) and Zero Hour! (1957).

Arthur Hailey, the author of Zero Hour!, would revisit his story just over a decade later with Airport, which would not only spawn several sequels but a satire of the genre, Airplane! (1980), whose broad but well-aimed gags make it impossible to watch The High and the Mighty without an inner voice echoing lines like "Looks like I picked the wrong week to quit sniffing glue" and "Have you ever been in a Turkish prison?"

Now, of course, it feels like disaster movies are ubiquitous, replacing the musical and even the romantic comedy, since too many sci-fi pictures are just disaster pictures threatening the world with everything from rogue asteroids to terrorists, climate change and alien invasions. (After 9/11, though, the plane-in-peril film seemed to nearly disappear.) It's hard to be an adult and watch a superhero picture and wonder how they'll ever rebuild Manhattan, Cairo, San Francisco, Paris, Lagos, London, Washington D.C., Tokyo, Gotham and Metropolis, and why we keep imagining our world being destroyed.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.