The United States will be going to the polls in a couple of days and no matter who wins, I'm guessing we'll be lucky if there aren't riots – or worse. Whoever takes the White House will not enjoy a placid term in office. From the perspective of 2024 it feels like American politics has been broken, and that it isn't much better in Europe (or even a farm team country like Canada, which is where it gets personal for me.)

For many of us it feels like things have never been worse, but that might be a purely subjective take. It's worthwhile to try to remember when America might have been some place like this before, and for that we have to go back to the '30s and '40s, to a novel and a 1949 movie called All the King's Men, and the Kingfish: Huey P. Long, governor of Louisiana and U.S. senator.

Long was, according to Robert Penn Warren, the author of the 1946 novel All the King's Men, "a remarkable set of contradictions, still baffling to biographers." He was, Warren wrote in a New York Times article published in 1981, "a focus of myth" and a "power...for good and evil."

Living in Louisiana during the heyday of Long's reign – there's no better word – Penn Warren wrote that "you knew that you were not seeing a half-drunk hick buffoon performing an old routine, but were witnessing a drama which was a version of the world's drama, and the drama of history, too, the old drama of power and ethics."

Robert Rossen, a screenwriter (The Roaring Twenties, The Sea Wolf) and the director of two minor film noirs (Johnny O'Clock, Body and Soul), was given the job of turning Penn Warren's Pulitzer-winning novel into a movie, and begins in a newsroom with Jack Burden (John Ireland), a reporter given the bottom-of-the-assignment-sheet task of writing about a political novice running for treasurer in some dusty county. His novelty, his editor tells him, is that "they say he's an honest man."

Willie Stark (Broderick Crawford) is honest enough to be headed for defeat against the local political machine headed by Tiny Duffy (Ralph Dumke), the local boss. Burden arrives in time to see Stark's street corner speech broken up on Duffy's orders by the local police, who confiscate his camera. He goes to the pool hall to ask for the camera back, and to register his protest against what looks to him like a violation of freedom of the press and Stark's free speech.

"We all believe in free speech," Duffy drawls for the amusement of his stooges. "We got to. It's in the Constitution."

What Kanoma County looks like is a single-party state in function, with authoritarian tendencies in service not to any particular ideology except graft – like the low-bid contract rewarded for the local school that Stark complains about in his speech. Burden decides that Stark is the underdog and idealist and writes him up with a glowing series of articles.

His assignment complete, Burden heads home to Burden's Landing, the family homestead where he does his best to avoid his stern, glowering father and alcoholic mother to spend time with his best friend Adam Stanton (Shepperd Strudwick), a doctor, and his sister Anne (Joanne Dru), his sweetheart. They're the children of a former state governor, a man whose memory is revered, and live with their uncle Monte (Raymond Greenleaf), a retired judge.

The Burdens and the Stantons are country gentry, and Jack spends his vacation fishing, sailing, playing tennis and dancing at parties. But his stories about Willie Stark have been noticed. Some, like Judge Stanton, think Stark's fight for the poor and against corruption is admirable. Others, like his father, think he shouldn't have been permitted to write about him as it will just "incite people." Men like Stark are just "log cabin Abe Lincolns with a price tag on them" – a price that will get steeper the higher he rises.

Burden's father embodies a powerful establishment cynicism that his son is trying to rebel against even when his father's money is making up for the shortfall in his reporter's wages. He tells Anne that he doesn't care about the money and begs her to wait for him until he figures out what he wants to do with his life. He cuts his vacation short and arrives back at the paper to learn that Stark has lost his bid for county treasurer, to no one's surprise.

But as Jack says later in the movie: "You got the wrong guy. I'm not the hero of this piece." And because he isn't Rossen's camera returns to Stark back in Kanoma County, getting his correspondence school law degree with the help of his wife Lucy (Anne Seymour), a former schoolteacher, and setting up practice representing the poor of the county.

And then disaster strikes – a staircase collapses at the school built with graft that Stark warned about, killing several students. At the funeral he's swarmed by parents telling him he was right and that they should have supported him. Crawford allows a hungry look to flash across Stark's face – vindication, no doubt, but also a sudden surge in ego and an intuition that this is the kind of opportunity from which power grows.

He fights and wins a lawsuit on behalf of the parents, then throws himself into another election campaign, unaware that he's being used as a spoiler by Boss Duffy's machine to split the vote. Jack follows him around on the campaign trail, as much adviser as reporter, along with Sadie Burke (Mercedes McCambridge), one of Duffy's operatives. She lets him write his own speeches – dull but worthy pledges to balance the budget – but one night they get the teetotal Stark drunk and upbraid him for falling for Duffy's ploy.

Hungover but galvanized, Stark changes tactics and begins attacking Duffy and the state's political machine, building massive grassroots support and threatening to become more than a spoiler. The machine rallies, and when Jack is told to stop writing about Stark – "I work here. I take orders," his editor tells him – he quits the paper. Stark loses but has had a revelation about how power works and spends the next four years preparing his next bid for governor, building his own machine around him.

Stark starts with Sadie, then co-opts Duffy's crew and adds Sugar Boy (Walter Burke) as his driver and bodyguard. By the time he recalls Jack from the wilderness, where he'd been blackballed by newspapers and scrounged for work, he's suddenly very well-funded; Rossen flashes a montage of cheques from supporters like oil companies, though Willie insists that "I don't need money. People give me things."

Jack takes Stark to Burden's Landing to appeal to the state's gentry, and with the obvious exception of Jack's father and the skepticism of Adam, he gets it, his charisma overcoming their suspicion of his motives and goals, with Anne becoming a particularly ardent supporter. "Good comes out of bad," Willie says, standing under a portrait of the late Governor Stanton. "Because there's nothing else it could come out of."

Every American adult watching All the King's Men when it was released would have known that Willie Stark was Huey Long, even though the film scrupulously avoids mentioning Louisiana or Baton Rouge (or the Democratic Party). Everything about Willie Stark's rise to power conformed closely to the myth of Huey Long, though Long's first run for office – after he had begun practicing as a lawyer – was a successful one for a seat on the Louisiana Railroad Commission.

Long himself played fast and loose with his own story: he loved to say that he was born in a log cabin, though that cabin was actually a comparatively grand two-storey affair, and by the standards of impoverished Winn Parish, his birthplace, his family were positively middle class, his father an independent farmer with considerable acreage, and his sisters would spend their lives trying to correct their brother's tales about his humble origins.

He came third at the 1924 Democratic primary in his first run for governor, losing because he didn't have the support of the party's Old Regulars and the Klan. But like Willie Stark he learned from his loss and capitalized on the state's mishandling of the 1927 Mississippi flood to build up his base among the poor – a considerable one in a poor state like Louisiana. He used radio and sound trucks to broadcast his message; when incumbent governor Oramel H. Simpson called him a liar in the lobby of the Roosevelt Hotel in New Orleans, Huey punched him in the face. Long beat his Republican opponent in 1928 with a crushing 96% of the vote.

Long embraced William Jennings Bryan's slogan "Every Man a King" and styled his programs after the Populist Party, which had its brief but influential heyday during Bryan's run in the 1896 election, when Long was just a boy. He said the governor's mansion was inadequate and personally supervised while convicts tore it down and replaced it with a grander one that he barely lived in, preferring hotels in Baton Rouge, New Orleans and, later, Washington. He also built a new capitol building, with an apartment for himself on the 24th floor.

But he also built highways, bridges, hospitals and schools, provided free textbooks to those schools and lavished money on Louisiana State University, with a particular emphasis on its football program, in which he took a personal interest, publicly firing its coach (he had to backtrack when LSU won against Tulane just before the firing took effect) and attempting to call plays from the stands. He effectively ran the equivalent of Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration (WPA) in Louisiana before FDR was elected and ran up state debt from $11 million to $150 million in seven years.

All this was done within a system of kickbacks and graft that enriched Long and everyone around him, but he objected when his politicians were caught taking too much too openly. He didn't begrudge his men a little "sweetening" but insisted that it was kept within reasonable limits. As T. Harry Williams wrote in Huey Long, his biography, this wasn't "on moral grounds...but on a concept of what was sound politics: if the corruption got out of hand the machine, and hence the whole political structure, would be weakened. Or as he perhaps would have put it, large-scale political grafting was politically immoral."

In Rossen's film Willie Stark's growing corruption mirrors his growing appetites, and particularly his quick transformation from teetotal to alcoholic; he's always reaching for a drink or offering one to someone. He also becomes sexually voracious, cheating on his wife first with Sadie and then any willing young woman who'll pose for a newspaper photo with him, and finally with Anne, with whom Jack had been chaste, regarding her as his paragon of virtue and (ultimately) his reward for making something of himself.

Stark also seduces her uncle, Judge Stanton, offering him a job as Attorney General, and Adam, for whom he promises to build a state-of-the-art hospital. Both men become disillusioned with Willie, and the judge becomes leader of the small but growing opposition to Stark's increasingly dictatorial regime. Jack, who had compiled a "black book" of blackmail material against Stark's enemies, discovers a long-buried bribery scandal in the judge's past but hides it from Willie – but not from Anne, who can't stop herself from sharing it with the governor.

Everyone from Burden's Landing eventually becomes disillusioned by Stark and their role in his success. Jack bitterly reflects to Anne that "There's no God but Willie Stark. I'm his prophet and you're his –" leaving the last word unspoken. Harshest of all is the certainty that his father had been right all along, and that cynicism is the only reasonable response to a political animal like Stark.

The film throws in a subplot involving Tom (John Derek), Willie's adopted son, who goes from his first foot soldier to football star at the university Willie pays for, becoming spoiled and sullen along the way, accidentally killing a girl when he drunkenly crashes a car, left paralyzed in a wheelchair when Stark insists that Adam operate on him before specialists can arrive. His role is little more than the first casualty of karma for Willie. (In real life Long's son Russell would follow his father into the U.S. Senate and represent Louisiana there for almost forty years. Long's brother Earl would succeed him as governor of Louisiana for three non-consecutive terms.)

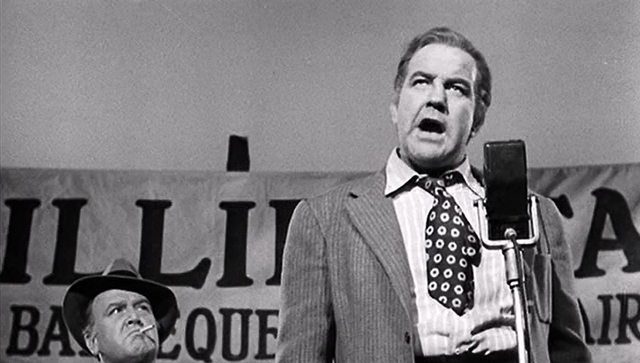

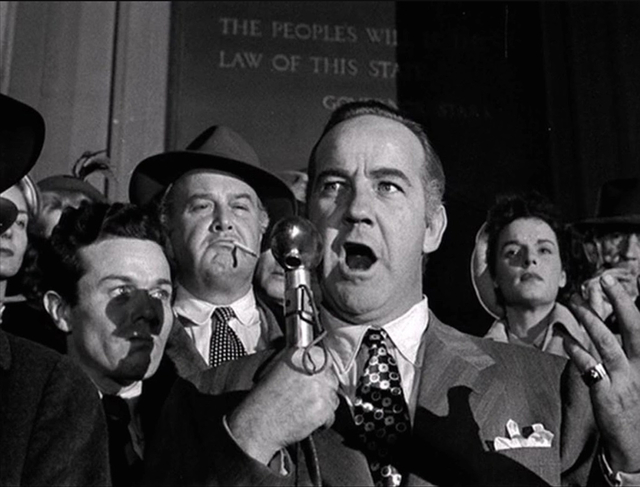

All the King's Men was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won three, including best picture. Crawford won for best actor, beating Gregory Peck in Twelve O'Clock High and John Wayne in Sands of Iwo Jima. It's easy to see why; his Willie Stark is a big performance with a tragic arc, and one based on a real-life character whose reputation was known by Academy voters and moviegoers. He modulates his transformation from honest man to corrupt boss magnificently, starting with that first hungover speech after he learns he's been Duffy's dupe.

Mercedes McCambridge won for best supporting actress, in a field that included Ethel Barrymore and Ethel Waters in Pinky and Celeste Holm and Elsa Lanchester in Come to the Stable. There weren't many actresses like McCambridge back then, and she was a harbinger of a new kind of screen persona that would emerge from the theatre and hit the movie screen in the '50s.

Radiating intelligence instead of sexiness or charm, her Sadie is both emancipated and unhappy. Her showcase scene is in front of a mirror after telling Jack about Willie and Anne; she examines her face, pulling at it and telling Jack about the smallpox she had as a child that left her scarred, her face hard. She's strident and confident and unique among the film's characters in that she's blessed and cursed with perfect self-knowledge.

John Ireland was nominated for best supporting actor (against Dean Jagger in Twelve O'Clock High, Ralph Richardson in The Heiress and James Whitmore in Battleground) but did not win. Once again it's easy to see why: his Jack is a hangdog character, nursing self-pity and self-loathing in alternating proportions and aware that he will always be a background character, roughly sketched, in any landscape that features a Willie Stark.

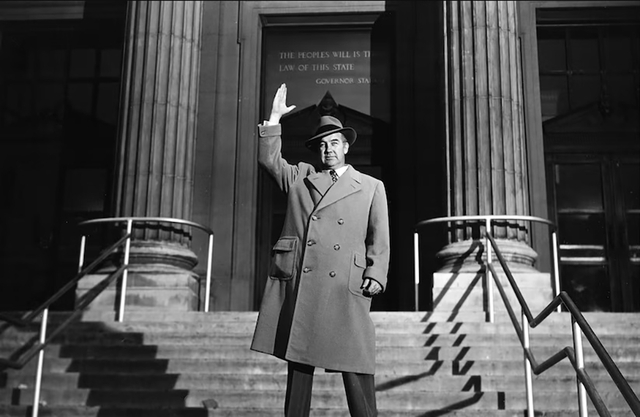

At the end of the film Willie survives impeachment (as did Long) and emerges triumphant on the capitol steps to address his crowd of supporters, where he's gunned down by Adam in revenge for driving Judge Stanton to suicide. Huey Long was shot in the lobby of the capitol he built by the son-in-law of a political opponent, Judge Benjamin Pavy, whose district he was about to gerrymander out of existence.

The gunman, Carl Weiss, was shot at least 60 times by Long's "Cossacks" or bodyguards; Sugar Boy and the state troopers kill Adam while Willie dies, muttering about "the whole world...Willie Stark." Anne tries to shake Jack out of his torpor and shock by imploring him to help tell the truth about Stark, pointing at the shocked mobs surrounding the capitol.

"Look at these people," she says. "Look at them. They still believe."

Huey Long was buried under the lawn of the Louisiana state capitol, under a huge statue of him. His legacy would be carried on by his family, but almost nobody today remembers how much of a threat he posed as a senator while still running his state with an iron hand. He was FDR's only plausible opposition in the 1936 election and could have either beaten the president in a primary or thrown his weight behind a third-party candidate who would have split the Democratic vote and set the stage for Long's victory in 1940, just before America entered World War Two. Long was the biggest obstacle between FDR and his four terms as president – an unprecedented violation of unofficial tradition that led to the passing of the 22nd Amendment.

There's a lot of alternate history there, not to mention lingering conspiracy theories that FDR and the Democrats had a hand in Long's death. Inside Louisiana, among his poor supporters, he was idolized for generations; outside the state he's remembered more often than not as the potential leader of what could have become American fascism.

Robert Penn Warren, recalling Long for the New York Times in 1981, wrote that "you heard the argument among true believers that Long, in that moribund and self-satisfied state of Louisiana, had chosen the only means to deliver his social goods. But this was, of course, the alibi of all grabbers of power everywhere. It was said all around Louisiana, and I, in certain moods, may well have said it myself. True, it was the alibi of Mussolini and Hitler, and every Communist and fellow traveler loved to mouth the cliche that you can't make an omelet without breaking eggs. (And that was to be their alibi for Stalin after the Moscow Trials a year or so later.)"

I had expected a lot of comparisons of Donald Trump to Long starting with the 2016 election, but the era of the Kingfish is ancient history now and young journalists today struggle to explain what Watergate was about. The Atlantic, a once-august publication driven to hysteria by Trump, is fond of making the comparison: in a 2019 article they called Long a "Trumpian" figure, and this year they hosted a podcast comparing Trump to Long, who they called "America's first true dictator," imagining a scenario where Trump would use Long's playbook to effect a coup d'etat.

It's a hell of a charge, and it might have resonated if anyone really knew anything about Long anymore. We had certainly forgotten about the Kingfish by 2006, when Sean Penn played Willie Stark in a new adaptation of Penn Warren's novel with no less than James Carville as an executive producer – a flop that made worst-of-the-year lists and was called "overwrought and tedious" by the New York Times.

Last year Politico plainly stated in an opinion piece that "Donald Trump is Our Huey Long." Writer Rich Lowry admitted that Trump is "not literally a 21st Century Kingfish. There are major differences between the two" and Long, with his "Share the Wealth" movement, was a

"man of the left" with a "socialist-infused populism that bears a strong resemblance to the program of Bernie Sanders."

Trump's support is nowhere near as total as Long's, he's nowhere near as deft or ruthless a political operator, and "Baton Rouge circa 1933 isn't Washington, D.C. circa 2023."

"In a prospective general election in 2024, Trump wouldn't be running in the equivalent of Louisiana," Lowry admits, "and he's in the legal clutches of authorities he doesn't control and are presumably immune to his charms and his intimidation."

"That said," he insists, "there is much that is almost exactly identical, from the gift for attention-getting, the politics of personal vituperation, the knack for exploiting new media, the rural base, the hostility to elites and urban areas and the message of resistance to powerful interests said to be disrespecting and threatening the common man."

Comparing Trump to Long requires some reading, some knowledge of context and, most important of all, an understanding that there are issues in play right now – the polarization of voters, the rapid decline of old media and the rise of a less controlled new one, the expansion of executive power and the systemic breakdown of a federal republic anticipated by the founding fathers – that make the comparison facile, even for smart people.

And we're not smart people, but rather the sort of people for whom comparisons to Hitler are sufficient, even comforting, as they flatter the person making them with the idea that they're the kinds of people who would have protested the rise of a Hitler, despite the personal costs. An attractive fantasy, but a stretch in a time where – unlike audiences or even Academy voters in 1949 –no one can even remember the who or the why of Huey Long.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.