My grandmother believed in ghosts. More specifically she believed in the ghost of my uncle Alec, her only son, who died when he was still a boy of – depending on who you talked to – either membranous croup or an infected needle administered by a drunk doctor. His ghost, or so my mother told me years after my grandmother passed, appeared to her and told her not to grieve.

Since I would hear about Alec's ghost over a half century after his sad death, it's safe to say that my grandmother, my mother and her sisters continued to grieve. I remain a skeptic on all things supernatural but I don't doubt my grandmother's conviction for a second, and I am sure most people who share my skepticism have similar stories from among friends or close family.

My grandmother had her ghostly encounter when Spiritualism was still a major movement, with famous adherents like Arthur Conan Doyle, its popularity grimly boosted by millions of deaths caused by the Great War and the Spanish Flu epidemic, to which my uncle Alec was just one incidental number added to the total. What people knew about ghosts then – besides all the table rapping and ectoplasm and ghost photography – came from books and folk tales in addition to whatever pseudo-science Spiritualism espoused to give it legitimacy.

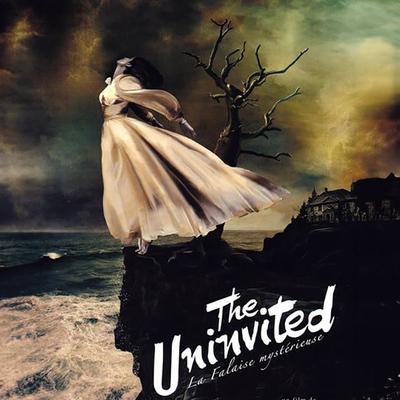

Horror was a movie genre from the start, but film would not add substantially to popular ghost lore until talkies, and then strictly for laughs in films starring Bob Hope, Bud Abbott and Lou Costello – horror spoofs where hauntings and monsters turn out to be con jobs. That was until near the end of another world war and the release of The Uninvited (1944), the beginning of the modern movie ghost story.

The film begins on the coast of Cornwall, and the voice of Rick Fitzgerald (Ray Milland) telling us that these are known as the "Haunted Shores" and that "It's not that there are more ghosts here, it's just that the people who live here are more aware of them." There's not a lot of space for skepticism with this statement, and the audience has been put on notice up front.

Rick and his sister Pamela (Ruth Hussey) are the kind of people who decide to buy a massive old house near the edge of a cliff on a whim – Windward House in this case, discovered while hiking the sea-battered cliffs on a day trip from London. They make an offer – £1800! – to Commander Beech (Donald Crisp), the owner, which gets accepted immediately, against the wishes of his granddaughter Stella (Gail Russell), who spent her early childhood in the house with a mother and father, now both dead.

Windward House is far from your usual decrepit, gothic pile; bright and airy thanks to abundant windows looking out to sea, the only time it seems sinister is at night. With few mod cons, it's lit by lantern and candle – a big help to cinematographer Charles Lang Jr. (A Foreign Affair, Sabrina, Some Like It Hot) who fills the screen with deep, inky blacks that suck the feeble light away. And then there's the sudden chills that fill a room, along with the overpowering smell of perfume and the sounds of moaning and sobbing just before dawn.

What Commander Beech neglected to tell Rick and Pamela was not just that his daughter had fallen to her death from the cliffs outside the house, but that she was one point in a romantic triangle with her husband Mortimer, a painter, and his favorite model Carmel, a Spanish gypsy. All three of them had lived in the house together until the birth of Stella, but that ended in tragedy after Carmel returned from Paris, where Stella's parents had sent her after paying her off.

Carmel had died not long after at Windward, and the new owners are being haunted by not just one but two lady ghosts. Stella is hopelessly drawn to the place, against the wishes of her grandfather but encouraged by Rick, who becomes attracted to the lovely young girl. The Fitzgeralds invite her for dinner, and then a séance when (as one does) they set about investigating the haunting with the help of Scott, the local doctor (Alan Napier, later Bruce Wayne's butler Alfred on the camp '60s TV series Batman).

The Uninvited was Gail Russell's first major part, after being discovered as a teenager and billed as the "Hedy Lamarr of Santa Monica." We've encountered Russell in this column before, in Budd Boetticher's western 7 Men From Now, near the end of her career when you can read the effects of alcoholism on her face. It was Russell's eyes that were highlighted as a starlet, described as sexy or expressive, though by the time she co-starred with Randolph Scott in Boetticher's film they had become puffy and squinting.

It's easy to see what that Paramount studio scout saw in Russell in The Uninvited. She might not be the greatest actress, but she's lovely and more than delivers on her character's barely-hidden fear and anxiety – a young girl who claims that she never felt loved until she was in the presence of her mother's spirit.

Russell was cripplingly shy and should probably never have been forced into acting, but her family needed the money. She apparently started drinking between takes while working on The Uninvited, at the urging of a makeup artist who said it would calm her nerves. Barely twenty at the time, it spiraled into a lifelong affliction that led to two major car accidents and her death in 1961, just 36, alone in her Brentwood home.

Milland's performance also does a lot to sell the uneasy mood of director Lewis Allen's film. He was the son of a Welsh steel mill manager and a mother who abandoned her family on more than one occasion. He left home to work on a tramp steamer at 15; a tattoo he got as a souvenir on the voyage – a skull with a coiled snake – gave him blood poisoning that nearly cost him an arm.

He struggled as an actor until the late '30s when he finally hit it big with roles in films like Three Smart Girls and Beau Geste. It would take longer for Milland to find the kinds of roles that explored the tentative, even tortured side of his personality; Billy Wilder and his then-writing partner Charles Brackett seemed to understand Milland well, choosing him for the male lead in The Major and the Minor and The Lost Weekend. (Brackett was the associate producer on The Uninvited.)

There's a great scene where Milland's Rick tells his sister to remain calm while they try to find the source of the wailing in their darkened house, but while Hussey's Pamela remains cool to their spirit infestation Milland becomes increasingly agitated. In another scene, while discussing turning the painter's studio with its wall of windows into a place where he can write his music, Rick is overcome by the chill and the sour mood of the room, slumping down and complaining about a "draining of warmth."

But Milland finds a way to tie this into Rick's low-key despair over finding success as a composer, an implied writer's block, and an intimation that he suffers from the peculiar handicap of being a man for whom things have come too easy. Not the sort of character who elicits an excess of sympathy, but Milland actually makes you feel sorry for good-looking, financially comfortable Rick with his little sports car, big country house and his partner-in-crime sister.

When analyzing The Uninvited, critics are fond of talking about its impeccably drawn mood – in what is suggested more than what is actually seen. From the hungry shadows that fill Windward House at night to a shot of Russell running across the lawn to the ocean at night, her gauzy gown backlit by the soundstage moonlight, Allen (a Broadway director before moving to Hollywood) is responsible for so many of the visual markers that have populated cinematic ghost stories for subsequent decades, from The Haunting to Carnival of Souls to Poltergeist to Crimson Peak.

But the film has some lapses in tone that can be chalked up to both the time it was made and creating a genre of film virtually from scratch. There are frequent gags, one-liners and comic set pieces, like chasing Pamela's cairn terrier through the empty rooms of the house, and the Fitzgeralds' housekeeper Lizzie (Barbara Everest). She's as superstitious as an old Irishwoman would be in any film made for decades, outraged at discovering the evidence of their séance and (like my grandmother) particularly sensitive to the presence of ghosts.

This kind of light touch would be banished from movie ghost stories in time, in favour of increasingly oppressive moods and characters who are never far from their breaking point before they unlock the front door of that old dark house.

A new character is introduced halfway through the film, introducing a plot point that's a throwback to 19th century gothic fiction. Miss Holloway (Cornelia Otis Skinner) was nurse and confidant to Stella's mother, and one of the only witnesses to her death. She has prospered since then, opening a high-end mental asylum named in the honour of her late friend and employer (motto: Health Through Harmony).

Commander Beech has Stella committed to the asylum against her will, apparently unable to see that Miss Holloway's devotion to his daughter is actually a crazed infatuation. Skinner plays Holloway as a camp villain, a close sapphic cousin to Rebecca's Miss Danvers, and didn't get past Fr. Brendan Larsen of the Catholic Legion of Decency, who wrote to Hollywood censor Will Hays that "large audiences of questionable types attended this film at unusual hours" attracted by "certain erotic and esoteric elements in the film."

There's a climax involving a mad dash in a car to outrace a train, a fatal heart attack and a revelation about illegitimacy and true parenthood. And there are ghosts. We'd glimpsed one before, but Allen doubles down at the finale, showing us not one but two of the spirits haunting Windward House revealing themselves and their motivations.

Special effects in the '40s were more than capable of rendering spirits – capable enough that no less than James Agee wrote in The Nation that despite a "mediocre story and a lot of slabby cliches," it was still "harder to get a fright than a laugh, and I experienced thirty-five first-class jolts."

Allen hadn't wanted to show the ghosts, but Paramount insisted, though film censors in the U.K. – working to priorities known only to them – had the spectres excised from the British version of his picture. English critics applauded the director for his creativity and restraint.

If The Uninvited reminds me of any film it's Otto Preminger's Laura, which came out the same year, a proto film noir that begins more like a ghost story, complete with Dana Andrews' cop becoming obsessed with a portrait of the dead woman hanging on the wall of the room where she was killed.

The two films had another thing in common. David Raskin's theme song for Laura became a hit and an abiding jazz standard after Johnny Mercer put lyrics to the melody, and "Stella by Starlight" – the song Rick writes for Russell's character when he overcomes his writer's block – became just as famous when Ned Washington added lyrics to soundtrack composer Victor Young's theme tune. (Chet Baker and Tony Bennett did two of my favorite versions.)

Milland seemed to hit his stride after The Uninvited, appearing in films like Frank Borzage's war drama Till We Meet Again and Fritz Lang's very strange spy thriller The Ministry of Fear before The Lost Weekend won him an Oscar. He worked until the mid-'80s, in pictures like The Big Clock, Dial M for Murder, X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes, Love Story, Frogs, The Thing with Two Heads, Escape to Witch Mountain and Battlestar Galactica.

Lewis Allen and Gail Russell were teamed up together immediately for Their Hearts Were Young and Gay, based on Cornelia Otis Skinner's memoir, with Russell playing Skinner. The studio then put them together again in The Unseen, a picture the public were obviously meant to mistake for a sequel to The Uninvited, though they share nothing in common. Allen would spend the '40s and '50s making noir pics (Desert Fury, Appointment with Danger, A Bullet for Joey) before easing into TV with episodes of Bonanza, The Fugitive, Mission: Impossible and Little House on the Prairie. Gail Russell's career, sadly, commenced its slow but tragic trajectory.

It would take a while for the groundbreaking decision to treat ghosts as real would inspire a thriving horror subgenre. There would be The Innocents and The Haunting, but momentum picked up in the '70s with films like The Amityville Horror, The Legend of Hell House and The Shining till today, when my grandmother's simple but ardent faith is hard to find, while moviegoers abandon all skepticism when watching films where spirits are very real, often sinister and usually malevolent, and the afterlife is an overcrowded waiting room that spills over into our world.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.