The final shot of Roy Ward Baker's 1967 classic British sci-fi film Quatermass and the Pit is one of the most indelible movie finales: a single long take of two characters silently reflecting on everything that's happened, while the end credits play over the shot. It captures two people trying to process shocking revelations – about themselves and humanity as a whole – in a moment that films like this rarely pause to capture.

Dishevelled and grimy in the dim blue dawn light and hot glow from burning buildings, the only two survivors of the quartet of main characters we've witnessed for the last hour and a half are waiting to see what happens next. Professor Bernard Quatermass (Andrew Keir) stands on the left side of the frame while Barbara Judd (Barbara Shelley) sits, her back against a brick wall, on the right. They occasionally glance at each other with looks that betray their anxiety and might, in a different situation, resemble post-coital regret.

I imagine it's a moment not unlike one shared by survivors in the immediate aftermath of a battle or a great war; people who've discovered something about what they're capable of under duress, unsure about who else might still be alive, or if they're on the winning side. They're waiting for the authorities to appear and restore order without any real relief, as the ordeal has revealed how their power and intentions are both hollow and unworthy of trust.

Perhaps they're even giving a few thoughts to their ancient alien insect overlords.

Production on Quatermass and the Pit had been in limbo for years. It was the third installment of a series written by Nigel Kneale that began life as live BBC TV productions. The Quatermass Experiment, the first instalment, was broadcast in the summer of 1953 and was a massive hit, but only the first two of six episodes were recorded, in poor quality. The sequel, Quatermass II, was broadcast in the autumn of 1955 and was another huge hit, so Kneale wrote Quatermass and the Pit, which aired in the winter of 1958.

Hammer Film Productions, soon to be famous for its gothic horror pictures, bought the movie rights to the Quatermass stories and had Val Guest direct adaptations of the first two. The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and Quatermass 2 (1957) starred American tough guy actor Brian Donlevy as Professor Quatermass, the main character – casting that Kneale disliked immensely. A third picture was to be made by Guest and starring Donlevy but Hammer had made a production deal with Columbia Pictures, who did not like the story and passed on Kneale's script.

Hammer finally ended their deal with Columbia and began a new one with Seven Arts and 20th Century Fox, and the third Quatermass film was put back into production. Guest was no longer available (he was making Casino Royale, the most non-canonical James Bond picture, for Columbia) and Donlevy was out of contention. Baker (Don't Bother to Knock, A Night to Remember) was hired to make the first Quatermass film in colour and given the run of British MGM Studios in Borehamwood, whose soundstages and backlots had produced pictures like Mogambo, The Man Who Never Was, The World of Suzy Wong, Village of the Damned, The Haunting and The Americanization of Emily.

The film begins with the camera floating through the superb work of production designer Bernard Robinson – a convincingly run-down bit of West London, complete with brickwork stained by coal dust, lingering bomb damage from the war and Hobbs End, a London Underground station on the Central Line undergoing expansion. (This is obviously part of that 99.9% of London that did not swing in the '60s.) Navvies are digging through the muck and dirt at the end of a subway platform when they discover what looks like a human skull.

London has been inhabited continuously for two millennia, so a spade in the earth is likely to reveal a Tudor palace, a plague pit, a medieval church foundation or a bit of Roman villa. (Excavation for the Elizabeth Line recently uncovered Roman coins and skulls, a Tudor bowling ball, Mesolithic tools and, yes, a plague pit.) Once police are satisfied that they haven't discovered a crime scene the archaeologists take over – and begin a budget-busting delay in construction.

This introduces the first man of science we'll meet in the picture – Doctor Roney (James Donald) and his fetching assistant Miss Judd. Their presence both amuses and irritates the navvies, and they've discovered another skull when a workman uncovers the smooth, metallic panel of what is immediately suspected to be an unexploded bomb – a leftover from the Blitz. (UXBs are still being found in the London area at a rate of dozens per year; this year two were discovered during construction of singer Dua Lipa's mansion in North London).

A call is put in to Col. Breen (Julian Glover), a British Army martinet complete with swagger stick who is in the middle of a tense meeting about rockets and Moon colonies with Prof. Quatermass. The colonel is intent on directing the professor's research into the production of ballistic missiles and has just been made Quatermass' superior by the Ministry of Defense. But he began his career disposing of German bombs during the war, and his expertise is called upon with the discovery at Hobbs End.

He has just smugly suggested that the professor join him for dinner at his club to smooth over their differences, and brings him along to the dig, where the two men of science form a tentative bond against the colonel and everything he represents. In the meantime the navvies are replaced by soldiers, who continue digging and discover that the bomb is more like a spaceship. Not only that, but another hominid skull found inside strongly suggests that it made its way deep in the London soil five million years ago. (The U.S. title of Baker's picture was Five Million Years to Earth.)

The buried spaceship afflicts some of the soldiers with frostbite and is impervious to blow torches and even diamond-bit drills, and it emits a crippling hum when the drill operator tries to make a breach into what's apparently a cavity in the ship. This drives Breen, Quatermass and the operator away in pain, but when they return they find that a hole has indeed opened up, which begins to crack and expand and falls away to expose a crystal-walled hive full of what look like huge grasshoppers, which begin to decay on exposure to the air, bleeding out a green goo when Roney starts anatomizing them back at his museum laboratory.

At this point in the story things start moving fast. The revelations of Roney's discovery have profound implications, not the least of which is that aliens visited the earth when man was still in an earlier stage of evolution. Genius that he is, Quatermass starts making connections, building a theory that the aliens had visited us at a crucial stage in our development, and in the decline of their Martian home world, using their superior genetic technology to create altered apes more suitable to continue their legacy on a planet hostile to the insect invaders.

At the same time Barbara has started her own investigation of the area around the Tube station, to when "Hob" was a nickname for the devil, and finds that whenever the earth around Hobbs End was disturbed the locals were tormented by visions of devils, gargoyles and a "hideous dwarf." A row of abandoned houses across from the station creak ominously, scaring the wits out of a bobby who grew up in the area. Anyone – like a short soldier or the drill operator, both with conspicuous cockney accents – who gets too close to the craft is afflicted with these visions.

The most afflicted develop telekinesis, like the poor drill operator who stumbles away from Hobbs End in a flurry of trash, street furniture, and crockery from a food cart, before he collapses in a churchyard. This is where Barbara and Quatermass find him, in the care of a minister worried for his soul, in the throes of what looks for all the world like demonic possession, which fills the sacristy with the groaning sound of wind and throws furniture and candelabras around the room. At this point the film marries Kneale's dank little sci-fi story with trademark Hammer gothic horror.

(It would be over a decade before another British-produced sci-fi flick, Ridley Scott's Alien, managed a similar feat.)

Apparently the most disturbing part of Quatermass' theory is that Earth was once colonized by Mars. Colonialism would be a thorny subject in a British film in 1967; after the war made Indian independence inevitable, just the last few years had seen a steady stream of countries leave the British Empire: Sierra Leone and Tanganyika (1961), Uganda, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago (1962), Zanzibar and Kenya (1963), Malta, Malawi and Zambia (1964), Gambia and the Maldives (1965) and Guyana, Barbados, Lesotho and Botswana (1966).

The Empire was a sinking ship, and colonies would continue leaving for another two decades; imagining that Britain, never mind the whole planet, had once been a colony would have been like having your nose rubbed in it.

Even worse is the implication – never openly stated but demonstrated repeatedly – that receptiveness to the "visions" emanating from the buried craft is more common among what were once called the "lower social orders" and individuals with "overwrought imaginations": basically women like Barbara. And that this had been hardwired into our DNA by the Martian insects when they created that altered ape. We have to take in all this information in a rush as the film hurtles to its conclusion, but this is a British sci-fi picture whose premise is that the Victorians were right, that class is bred in the bone and that women tend to hysteria.

This wouldn't be sci-fi without the plot revolving around a piece of improbable technology. During one of our visits to Dr. Roney's lab we learn that he isn't just poking around with old bones: he and his team have bodged together a bit of kit that literally reads minds – or rather records what we see when our minds are at rest. (Apparently Loney, a bit of a toff, is given to dreaming of pastoral country lanes in Kent or Sussex.)

Desperate to prove Quatermass' hypothesis about alien insect colonizers to Breen and his bosses at the MoD, the boffins wire their mind-reader to a video recorder and bring it to Hobbs End to be closer to the alien craft and the source of the visions. The only person sensitive enough to create a strong signal for the recorder is Barbara, who becomes weightless as she's possessed by the Martian vision – a marvellously agonized performance by Shelley, the "Queen of Hammer", who judged that her performance as a woman turned into a vampire in Dracula, Prince of Darkness (1966) was the best of her career.

They record her vision and show it to the authorities – scenes of alien insect hordes marching and slaughtering each other that Quatermass describes as a "race purge" and a "cleansing of the hive." (It is, sadly, the most inadequate special effect in the film, and though we could produce an infinitely better one today, any remake of Baker's film would doubtless lose the grimy, oppressive tone that helps sell the story. If you have any doubts, just watch the BBC's own 2005 attempt to re-stage a live broadcast of The Quatermass Experiment with David Tennant as Quatermass. But Kneale himself described Hammer's special effects as "diabolical.")

To their horror, they discover that Westminster has already cooked up a cover-up – a story about the craft as a propaganda V-weapon launched by the Nazis and lost in the rubble and craters of the blitzed-out west end, concocted by Breen and his fiendish smirk. This official story is launched with an Orwellian flourish by the government at a press conference at Hobbs End, complete with loudspeakers on cars telling the public that there's nothing to see, move along please. (Kneale was also the author of a BBC TV adaptation of 1984.)

Unfortunately the generator provided to power the TV cameras and lights brings the alien craft back to life, though despite Quatermass' shouted warnings that they're in danger, the man from the ministry insists to the assembled press that "the official arrangements will proceed as planned." Moments later he's crushed by a television camera as the craft begins to glow and broadcast its message to the descendants of the altered apes, drawing Breen like a moth to its flame and burning him alive.

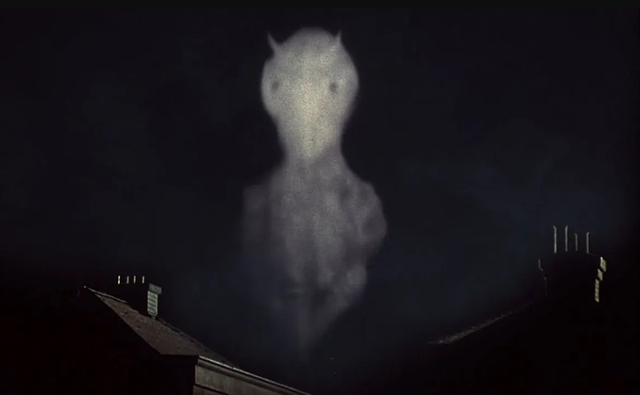

Outside on the streets the ground shakes, buildings collapse, fires break out and the population is moved to mass homicide, a genocidal impulse to purge the hive of mutations – like Quatermass himself tries to do with Roney, who's apparently impervious to the paralyzing alien broadcast, which resolves itself into a huge, glowing projection of a demonic horned Martian insect in the night sky above Hobbs End. This was the image from the film that lingered with me for decades after I watched Quatermass and the Pit one chilly Sunday afternoon, broadcast on American television from Buffalo, NY across Lake Ontario.

Baker's film commits to this climax of chaos and bloodlust, with its hordes of citizens united by race memory, using telekinesis to seek out mutations in their midst and crush them under the weight of falling masonry. (Blocks of brick and stone that land with the obvious bounce of Styrofoam.) Shelley's Barbara is caught up in the genocidal moment, glaring at Quatermass as he tries to fight the alien signal and bring her back around; a feat he only manages with the sharp blow we expect from Van Helsing rousing Mina Harker from Dracula's trance, before carrying her off over his shoulder and away from unholy carnage.

Kneale's first two Quatermass stories were about rockets, alien infection and invasion, and secret government programs hiding more sinister agendas. The conventional take is that by his second film, Kneale's inspiration came from Britain's participation in NATO and the Cold War – from the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and the Aldermaston march, which would be fine if the BBC TV dramas hadn't aired years before the founding of the CND.

In the long run Kneale's Quatermass universe has played into a different paranoid strain in modern culture – into Ancient Aliens and Graham Hancock, Ancient Apocalypse and the conspiracy to obscure mankind's deeper history on the planet and even a prehistoric intervention into our evolution by visitors from space. Back when I saw Baker's film on American television the most salient expression of this was Erich von Däniken's bestselling 1968 book Chariots of the Gods and its 1970 documentary adaptation, which would combine with Bigfoot and the Bermuda Triangle in a sargasso sea of quack pop culture paranoia that set the tone for much of my '70s childhood.

Who knew that it would have such abiding appeal, or cultural longevity? But it's worth remembering that one of the productions that took over British MGM Studios in Borehamwood after Baker's Quatermass film was Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, a far more technically accomplished and influential picture, though it's been blamed for bankrupting the studio complex after it spent two years monopolizing the facility.

Of course, the alien visitors who alter the apes in Kubrick's film are disembodied and godlike, unlike Kneale's arthropod hordes, but Kubrick and Kneale did their parts – consciously or not – in selling the idea that humanity couldn't have evolved into space-going creatures without a bit of help. And the idea has exploded all over science fiction as it evolved – thanks to Quatermass and 2001 – from b-picture space operas to big budget cinematic spectacles. It's still there in films like Robert Zemeckis' 1997 movie version of Carl Sagan's Contact and Denis Villeneuve's Arrival (2016), and has colonized the Alien franchise with Ridley Scott's later ongoing (and tragically disappointing) sequels and prequels.

And Kneale's Quatermass universe has become a keystone to conspiracy theories like the one described in a series of YouTube videos by "Professor Simon", making connections to Britain's pagan past, Henry VIII's protestant reformation, masons, the fascist Green Shirts, the Woodcraft Folk, the royal family, the Notting Hill Riots, Jack Straw and Kubrick's Eyes Wide Shut. Like so many of these connect-the-dots treatises on hidden history, it leaps across logical chasms with exclamations of "Who knows?" But the idea is obviously out there, with the sole consolation that it isn't as daft or historically illiterate as tangentially connected ones about "mud floods" and Tartaria. (You won't thank me if you go down that rabbit hole.)

Which is why, after seeing the world set on fire, you have to sympathize with Quatermass and Barbara, silently absorbing the aftermath of a near-apocalypse and new knowledge about their world and the people running it that was likely unwanted. And it's hard to deny that, more than ever, citizens and voters are becoming unsatisfied with official explanations and conventional wisdom while being taunted with news leaks promising imminent revelations about alien contacts. Some of us doubtless find ourselves, at the end of every news cycle, looking as spent and overwhelmed as Keir and Shelley at the end of the picture.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.