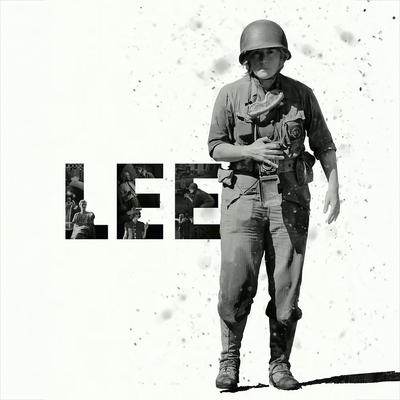

Lee Miller – model, muse, photographer, war correspondent – was hardly unknown, so the makers of Lee, a newly released biopic about her, had an opportunity to sketch in the vast amount of empty space around this thumbnail of Miller, her life and her work. They had the full cooperation of her son and biographer and keeper of her legacy, Antony Penrose, and the star power of Kate Winslet, who produced the film and plays Miller.

This gives the picture, directed by cinematographer Ellen Kuras, a provenance and authority that few biopics can match. Even if you didn't know anything about Lee Miller it's hard not to root for the film – the sort of (relatively) small budget, serious, literary and historical picture that once filled multiplexes and art houses and competed for Oscars until the end of the '90s.

But it's a long time since the era of Dangerous Liaisons, The English Patient, The Remains of the Day and Sense and Sensibility, and sometimes it seems as if we've forgotten how to make those kinds of films much as we can no longer make a really good movie musical. And so we end up with a film like Lee, which is undeniably worthy and meant for adults and redolent of quality when everything with a bigger budget goes down like dinner at a 7/11. But somehow it isn't actually satisfying, no matter how much you know about Lee Miller.

The film begins with a brief but vivid scene of Miller under enemy fire with her camera, at the siege of Saint-Malo after the Allied breakout from the Normandy beachhead won on D-Day. We see Winslet's Miller stumbling through a smoke-filled street while shells and bullets fill the air with debris, dust and metal.

She runs from place to place looking for cover, huddling in one spot long enough to train her camera and take a photo – a German boot lying on the ground with a belt of machine gun ammunition trailing out of it like a spine. It's the kind of off-beat, artistic and surreal image that made Miller's reputation not just as a war reporter but as an artist.

But before we can process it a shell bursts nearby, slamming her against a wall of sandbags and knocking her breathless. This is the closest to action that Miller would get for the whole war, and we'll learn later that it was a mistake – that Saint-Malo was supposed to have been pacified though no one told the German garrison holding out in the Citadel overlooking the town.

After this we flash back to just before the war – to Miller in the south of France with her bohemian friends like the poet Paul Éluard (Vincent Colombe) and his wife Nusch (Noémie Merlant), a former circus performer, Miller's onetime lover the artist Man Ray (Seán Duggan), and Solange D'Ayen (Marion Cotillard), an aristocrat and the fashion editor of Paris Vogue. We know about idyllic picnics like this because they were photographed, and Kuras does her best to replicate one such gathering, where the women would sunbathe topless while the men sat fully clothed – the sort of déjeuner sur l'herbe that was apparently still popular with bohemians since Manet painted it in 1863.

Miller is introduced to Roland Penrose (Alexander Skarsgård), an artist and art dealer connected to the surrealists with whom Miller had been involved since the '20s, when she was a fashion model arriving in Paris after a successful career in America. They quickly become lovers, though the film doesn't bother telling us that she was already married to an Egyptian, Aziz Eloui Bey, and would remain so for most of the events that transpire in the film.

"I was good at drinking, having sex and taking pictures," Winslet's Miller says, "and I did all three as much as I could." In a framing device, we see Miller late in life, being interviewed by a young man we assume to be a journalist (Josh O'Connor) as they go through her photos in the comfy sitting room of an English country house, while Miller drains endless glasses of gin.

The idyll by the sea is, we quickly learn, a glimpse of a world about to end; a newsreel projected on a wall during one evening of this long party shows adoring crowds thronging Adolf Hitler. Lee and several of her friends wonder aloud that anyone could be taken in by the Nazi leader but Penrose assures them that he's no joke. One of the men proclaims that the only sane way to protest the onslaught of fascism is to paint; his friends echo that you also need to write and dance, and Lee and Penrose get up and fox trot while the newsreel footage of Germany and its leader flickers across them.

The elderly Lee tells the young man that, despite their clearly sinister agenda, nobody seemed able to do anything about the Nazis; that their rise happened so slowly, then so quickly, that the war was upon them before anyone knew what to do. Perhaps they really believed that it could be painted or danced away, hard as that is to believe.

In her biography Lee Miller: A Life, Carolyn Burke writes that "one could hardly underestimate the sense of dread felt by all those (avant gardists included) who saw the coming war as a threat to civilization – despite their critique of its values." Which is too often the tragedy of the creative class, who put so much energy into outrage and rebellion and defining themselves as not just outside the mainstream, but as an enemy of everything it holds dear, that they forget how much skin they still have in the game.

Living in London with Penrose when the war starts, Miller walks into the offices of British Vogue and asks for a job from its editor, Audrey Withers (Andrea Riseborough). She's put to work shooting fashion in the rubble of the Blitz, a job uniquely suited to the surrealist Miller; in one scene she improvises a shoot with two girls across the street from Vogue's office while it burns after a Luftwaffe raid, sitting them in the doorway of a bomb shelter and accessorizing them with bizarre visors meant to block the glare while fighting fires.

This is just one of many famous Miller photographs recreated for the film, though it has to be noted that this shoot actually took place at the entrance to the Anderson shelter in the garden of Miller and Penrose's house. These little alterations to the facts are forgiven in the interest of time and drama and visual impact, but not all the inventions in Lee are so easy to overlook.

While shooting the home front for Vogue, Miller meets David Scherman (Andy Samberg), a photographer on assignment from Life magazine in the lead-up to the invasion of Europe. They hit it off despite her combative attitude, and she invites him to move in with her and Penrose, a conscientious objector whose skill as a painter has put him to work designing military camouflage. They quickly become a menage a trois; Miller and Penrose had an open relationship that often made their menages quite byzantine.

In her biography of Miller, Burke joins the chorus of writers and historians who have suggested that Britain's sexual revolution actually began during the war. She quotes Time magazine foreign editor Charles "Wert" Wertenbaker in a passage in her book explaining how the unusual arrangement between Miller, Penrose and Scherman, which might have raised eyebrows in peacetime, didn't get noticed much during the war:

"Sex in wartime carried 'the demand to be casual,' Wert wrote, since no one knew if he would be alive the next day. The war 'made the English promiscuous,' he believed, but kept 'the deepest emotions for itself.' Going to bed with someone could be intensely private but also 'an irresistible expression of the forces around them...a gathering together of primitive passions and noble aspirations for the final orgasm of war.'"

Miller was used to having a complicated sex life; what really motivated her as the invasion of Europe loomed closer was getting accredited as a war correspondent so she could be close to the action, and she at least had Withers' backing at Vogue. But while the British military would send no female journalist or photographer anywhere near the battlefront, Scherman reminds her that she's still an American citizen, and that the Americans at least will send her across the channel and behind the lines.

Miscommunication gets Miller sent into an active war zone in Saint-Malo, where in the aftermath of the battle she witnesses women accused of sleeping with Germans having their heads shaved. Miller and Scherman, working as a team, race to keep up with the front as it moves on to the liberation of Paris, where Miller is reunited with her friends, most of whom had gone underground with the German occupation.

Some, like Paul and Nusch Éluard, had joined the resistance and spent the war in hiding. Her friend Solange had not been so fortunate: she's just been released from a German prison when Miller finds her, a shadow of her former glamourous self, while her son had been shot by the Nazis and her husband rounded up and sent away on one of the trains to places from which no one returns.

This stiffens Lee's resolve to follow the war to where it leads, hoping to solve the mystery of where those trains went. Despite Penrose imploring her to return with him to England she decides to join Scherman and go where the war is heading – to Belgium and Denmark and Luxembourg and from there across the Rhine into Germany.

It's what draws Miller and Scherman to Struthof, Buchenwald and Dachau, though the movie compresses their encounter with the concentration camps to simply Dachau. In Leipzig they document mass suicides by Nazi officials including the city treasurer, his wife and daughter, all dead in his office, a scene Miller finds it in herself to photograph with something like tenderness, at least in her pictures of the daughter in her Red Cross uniform, huddled as if asleep into the corner of a big leather couch.

Miller's photos of the concentration camps are among her best of the war, a series of images that transcend mere documentation. Writers and critics speculate that her background in surrealism primed her for this work, as if the deconstruction and dismemberment of people and things in the work of Max Ernst and Salvador Dali was a prelude, a way of helping Miller process the actual horror in front of her, once only imagined by the artists she had known for almost two decades.

In the film, Miller and Scherman are forced to confront the scale of the atrocities at a railway siding where a long line of boxcars are found piled with corpses. We see them shaken and overwhelmed by the spectacle, as we imagine we would be if forced to witness such a thing. But their colleague, photographer Margaret Bourke-White, who often showed up before or after them at places like Dachau, recalled that when "photographing the murder camps, the protective veil was so tightly drawn that I hardly knew what I had taken until I saw prints of my own photographs...I believe many correspondents worked in the same self-imposed stupor."

Scherman himself recalled that while photographing the camps Miller was "in seventh heaven, shooting a scoop of tremendous magnitude. She never stopped to think about what she was seeing."

Lee is at pains to portray Winslet credibly as a photographer; they created a replica of the Rolleiflex she used, and even loaded it with film for Winslet to shoot the re-staged scenes that Miller covered. She does a pretty good job at it; many photographers in movies don't look like they have much of a connection with the tools of their trade, snapping away sloppily and barely glancing through the viewfinder. My only complaint, having used the same camera myself for over a decade, is that Winslet doesn't cradle the Rollei firmly enough when she's preparing to press the shutter as you learn to do, especially when shooting in low light, and much of the time Lee shows Miller shooting in stygian conditions.

(Perhaps off topic, but it's interesting that the cameras most often used by American photojournalists during the war – Lee's Rolleiflex, the Leica and Scherman's Contax – were German made, examples of how that country had a clear lead over the rest of the world in precision, high-tech industries in the '30s. It's the kind of thing that would lead you to assume that they'd be the winning side – if cameras won wars. Thankfully they didn't.)

The Dachau scenes are the crux of Lee, and they build to her taking a photo – an intense portrait of a little girl, her face full of trauma – that demonstrates the emotional price of photographing a place like Dachau for both the subject and the photographer, and becomes a key to unlocking Miller's empathy for the victims of the war, especially girls and women. The problem is that it didn't happen; the photo and the whole scene is made up, and no such portrait appears among Miller's work. It won't bother you if you know nothing about Miller going into the picture, but I found it jarring, especially as there's no shortage of powerful images made by Miller during her time in the camps.

Lee makes up another scene later in the film, after Miller has returned to London and Penrose (a homecoming that's shown as hushed and anticlimactic in the film but was in fact filmed for a Pathé newsreel in real life.) When the Victory issue of Vogue comes out she discovers that only one of her photos from the camps was published. In a rage she storms into their offices and begins destroying her work, tearing up contact sheets and cutting film negatives with a pair of scissors.

When Audrey Withers tries to restrain her, pleading that the photos are a priceless record and must be preserved, Lee shouts that they belong to her, and if they were so important why didn't she print them? Withers responds that she fought for her, but Lee spits back that she didn't fight hard enough. It's a powerful scene – as a photographer I winced as she sliced through those negatives – but it never happened as far as I can tell.

Withers wrote years later that "the mood then was jubilation. It seemed unsuitable to focus on horrors." But U.S. Vogue printed a whole spread of Miller's photos from the camps, under the headline "Germans Are Like This" and the bold-faced command to "BELIEVE IT." Miller's copy accompanying the photos was damning:

"Germany is a beautiful landscape, dotted with jewel-like villages, blotched with ruined cities, inhabited by schizophrenics."

Another really powerful scene in Lee is, thankfully, not made up. Fresh from Dachau Miller and Scherman arrive in Munich and are told about a place they should go – an officer's club in an apartment building that has electricity and running water. They arrive and discover that they're in Adolf Hitler's apartment; Miller and Scherman spy the bathroom and Miller goes in first, calling for Scherman and telling him to lock the door.

Together they stage a photo that would become famous and sits at the heart of the legend of Lee Miller, of the photographer naked in Hitler's bathtub, her muddy boots on the bathmat, a picture of the dictator propped up on the edge of the tub, Miller looking pensively over her shoulder and away from Der Führer. That night they'd learn that Hitler and Eva Braun had committed suicide in their Berlin bunker.

"We've all speculated where we'd be," Miller wrote to Withers, "what city and what friends we'd choose in the way of celebrations for the end of the war, or the death of Hitler...We couldn't celebrate more than we were already."

"I'm getting a very bad character from grinding my teeth and snarling and constantly going around full of hate," Miller wrote to Penrose from Germany. "I glare at their blossoms and plowed fields and undestroyed villages and work myself into such a state that I have no human kindness in me when I talk to their victims."

Winslet has been applauded for giving a brave and indelible performance as Miller, but the big problem with it is that she portrays Lee as peevish from the start, the angry woman Miller describes near the end of the war, but all the way through the picture. Miller could be strident and brash, yet recollections of her praise her charm alongside her beauty, and how she used that to talk her way in and out of places.

The film implies that this is how a talented, intelligent woman would respond to living in a sexist world. But Cynthia Ledsham, a friend of Schermer, recalled of Miller that "the atmosphere changed when she walked in, because of her joie de vivre. It's funny how someone so self-absorbed can buck up others, even while she got them to do just what she wanted." Lee doesn't show us much of this Lee Miller, so much that Schermer's devotion and the loyalty of friends like Solange seem unaccountable as a response to the flinty woman we see onscreen.

The film includes a brief scene in liberated Paris where Lee stops the rape of a young girl by an American soldier with a doughy, entitled face that looks more YouTuber than G.I.; she chases him away with a knife, which she hands to the girl saying, "next time cut it off." The Lee Miller of Lee is as angry at living in a sexist world as she is when she becomes one of the unlucky first few to discover the aftermath of the Holocaust.

As it gives the same weight to fictional interpolations as well as real events from Miller's life, Lee fails to allow the woman at the centre of the film to really respond to the events she witnesses, to actually change for better or worse as she willingly sets about chronicling atrocities the century couldn't have imagined just a few years previous. Her anger, it implies, is what makes her heroic, and not her rare ability to depict humanity and even beauty amidst those impossible crimes.

The picture's twist ending poignantly imagines Lee Miller as an absence sitting at the centre of her work as a war photographer. Somehow the film that was supposed to restore Lee to her deserved place as an artist and a witness to one of history's greatest tragedies ultimately leaves her the same enigmatic figure who began her career as a model and a muse. It doesn't seem fair.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.