Whit Stillman chose to set his second feature movie in Europe during the height of early '80s Cold War tension – roughly 1982 to 1984, around the time of KAL 007, two false alarms that almost triggered massive Soviet nuclear strikes, the brief rules of hardliners like KGB head Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko as chairmen of the Soviet Union, the Soviet boycott of the Los Angeles Olympics and the beginning of resistance against communist rule in Poland by the Solidarity movement.

We're told that it's "the last decade of the Cold War" before a bomb goes off at the American Library in Barcelona – a grim start to what's actually a comedy, a "fish out of water" story that will feature another bombing and an assassination attempt on one of the main characters. Of course, Stillman made Barcelona in 1994, a decade after the film's setting, and after the Cold War had ended without the anticipated bang but with very much more than a whimper.

It had been four years since Stillman made his outsized debut as a director with his very low budget feature Metropolitan, the story of a group of young men and the young women they escort to debutante balls during what they perceive as the waning days of their social class. Along with his next film, The Last Days of Disco (1998), it would become part of his "Doomed Bourgeois in Love" trilogy, also called his "WASP Trilogy" since his main characters come from and obsess about their social class and its fate.

Barcelona saw the return of two cast members from Metropolitan – Taylor Nichols and Chris Eigeman, who had effectively stolen the film from its putative lead Edward Clements, respectively playing the antagonist and mentor to Clements' Tom Townsend. Nichols and Eigeman had played the most indelible characters in Metropolitan, Tom's guides to the world of debutante season in Manhattan, one of them obsessed with its imminent doom, the other its most robust apologist.

In Barcelona they play cousins, Ted (Nichols) and Fred (Eigeman) Boynton, whose rhyming names suggest that, together, they might just comprise a whole man. They're Midwesterners; Ted is a salesman in the Barcelona office of a Chicago company making high speed motors, Fred a junior officer in the U.S. Navy, sent to Barcelona as the advance man of the Sixth Fleet before its visit to Spain.

They're relatives but not friends; Fred arrives late at night on short notice expecting his cousin to put him up for however long he might be in town. They were close, once – a period of maybe a day or two when they were boys, just before Fred borrowed Ted's kayak without asking and sank it in the lake where their families summer. This childish spat defines Ted and Fred as overgrown boys still a few life events short of becoming men, with the subsequent events of the picture comprising that journey.

In America neither man would stand out; in Barcelona they're anthropological curiosities, Ted with his hyperarticulate awkwardness, Fred for his boorishness (his cousin wonders if he was the right choice to run public relations for the fleet, and Fred agrees) and his dress blues. On their first night out after he arrives – Spanish cities are great places to bar hop until the sun comes up – Fred's uniform gets him called facha or "fascist" by passersby, which leaves Fred incensed, along with graffiti protesting "Yankee pigs".

Stillman spent the early '80s in Spain, working as a sales agent for Spanish films, even acting in a few, and Barcelona was inspired by life as an expat in Madrid and Barcelona. Spain had joined NATO in 1982 and, as part of the protest to this, Felipe Gonzalez and his socialist PSOE party won a landslide in that year's election that decimated the establishment parties, many full of leftovers from the Franco era, but polarized the country with massive gains by the right-wing People's Alliance led by former Franco minister Manuel Fraga, who became the official opposition.

Cities like Barcelona – which had always defined itself in opposition to the rest of the country and the Madrid government in particular – were socialist strongholds, full of anti-NATO (or OTAN, as it's called in Europe) protest. Whitman front loads his film with a lot of explosive political context but handles it all very lightly, mostly by balancing it with the romantic travails of Ted and Fred in the half of the plot that's less political thriller than dry romantic comedy.

This storyline is introduced by the first shot of Ted at the start of the film. Looking toward the National Palace of Montjuic across the Plaça de Josep Puig i Cadafalch we see several attractive young women in red jackets and black miniskirts looking like flight attendants for a luxury airline. They're the "trade fair girls" – a more elegant and educated version of what were once known as "booth babes" in the U.S.

Ted walks into the frame with his back to us, wearing his Brooks Brothers suit and carrying his briefcase. One particularly lovely trade fair girl smiles at him as she walks toward the camera; after a moment Ted stops and turns to look back, Stillman's camera catching a hilariously pained expression on Nichols' face. You get the feeling this happens to Ted at regular intervals, and that the time between those smiles is spent trying to restore his equilibrium. A young man – or anyone who was once a young man – will recognize this shade of agony.

On the night Fred arrives Ted tells him that in the wake of a painful break-up with his American girlfriend he's decided that female beauty is a trap – that the pursuit of physical beauty has "ruined lives" and that he's only going to pursue plain or homely girls and try to find the inner beauty that he thinks is necessary for love. Fred calls him "pathetic", wondering why he'd cut himself off from all those beautiful women, one of whom might in fact be his perfect match, though he scoffs at the concept. To both these twentysomething men, their logic is impeccable.

Ted's resolution is soon tested when he and Fred are invited to a costume party by Marta (Mira Sorvino), one of the trade fair girls, who assumes that Fred's uniform is fancy dress. He decides to pursue Aurora (Nuria Badia), the girl he judges most tolerably plain among Marta's friends, but she stands him up on the night she invited him to what he assumes is a jazz concert, sending her friend Montserrat (Tushka Bergen) in her place.

The night is a disaster; he thought they were seeing swing legend Lionel Hampton, but the concert actually features Vinyl Hampton, some sort of noisy ersatz jazz, popular with young Barcelonans that season, which puts Ted into a bad mood. They press on with the evening nonetheless, and when Ted confesses his motivation for dating Aurora, Montserrat says she can't believe he thought her plain when all of her friends consider Aurora a great beauty. (The disconnect between what men and women judge as female beauty – they're more likely to agree on male beauty, by and large – is one of many small but persistent disconnects that has likely always handicapped communication between the sexes.)

But along the journey from bar to disco to bar to disco (Spanish nightlife is both abundant and picaresque) Ted inevitably falls for Montserrat, putting his resolve to the test and opening him up to inevitable romantic torment. Fred, for his part, has quickly paired off with Marta, which puts them in the political and social crosshairs of this foreign city.

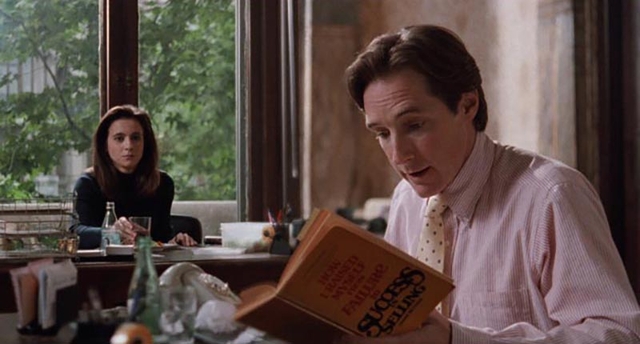

Nichols' Ted is a well-drawn evolution of Charlie, his character in Metropolitan. An old man trapped in a young man's body, he's smart but unworldly compared to Fred, and overthinks where his cousin works on self-serving instinct. He has found his identity as a salesman, devoted to what he considers the foundational texts of his profession – books by Benjamin Franklin, Dale Carnegie and especially Frank Bettger, a baseball player and salesman and author of best-selling self-help books like How I Raised Myself from Failure to Success in Selling.

Ted's earnest nature finds affirmation in Bettger, who councils plain-speaking and honesty even when it offers no short-term gains. This doesn't satisfy all of his self-doubt and Ted has turned to the Old Testament for advice, hiding his Bible inside a copy of the Economist. One of the funniest scenes in the film finds Ted alone after Fred and Marta have gone out, so he begins reading his Proverbs and Ecclesiastes while dancing to Glenn Miller, shuffling and high kicking across the floor of his apartment until he notices that Fred and Marta have returned to witness the mortifying spectacle.

"Is this some strange, Glenn Miller-based religious ceremony?" Fred asks.

"No, Presbyterian," Ted replies.

"Oh, this is your Presbyterian church?" Fred responds.

"Well, Protestant," says Ted.

"Protestant churches are like this?" Marta asks.

"Pretty much," responds Fred.

Where Ted strives for honesty, Fred is both a habitual liar and a casual thief, pinching small amounts of cash from Ted with vague promises of repayment. For fun he tells the trade fair girls that the stolid, apparently square and terribly American Ted – "like a big unsophisticated child" Fred explains – is actually a secret pervert, a devotee of the Marquis de Sade, who wears painful undergarments consisting of thin, tight leather strips under his clothes. It's a story Fred has told women about Ted before.

"Just once I'd like to go out with a girl not convinced I'm encased in black leather underwear," Ted complains to Fred when he learns that he's done it again.

"That bothers you?" asks Fred.

Lie or not, it makes Ted interesting to the trade fair girls, but Fred is still confused by his lack of gratitude. "Do you think any even mildly cool trade fair girl would give you the time of day if she knew the pathetic, Bible-dancing goody-goody you really are?" Fred responds to his cousin's complaints. "A least people into S&M have a tradition! We have some idea what S&M is about. There's movies and books about it. But so far as I know, there is nothing to explain the way you are."

Beauty is at the heart of what torments Ted and confuses both cousins. There's the beauty of Marta, Montserrat and the trade fair girls; in one scene Ted and Fred arrive early for an evening out and watch the girls dance Flamenco steps on the patio below them. (Every Spanish person assumes a knowledge and ownership of Flamenco culture that, sadly, very few of them can really claim.) They're transfixed, as if struck dumb by their luck.

And there's the greater beauty of the city around them, glimpsed in the background and from a car window, when Ted is showing his cousin around. He points out some highlights – the cathedral, the Roman walls – and compares it favorably to Michigan Avenue in his Chicago hometown. In a line cut from the film but found in Stillman's shooting script, Ted marvels to Fred: "I mean, look around – all this, everything we see, was built with sales."

In his essay about the film in Doomed Bourgeois in Love, a 2001 collection devoted to Stillman's trilogy, E. Christian Kopff writes that "this is the innocent provincialism that persuaded Oswald Spengler that there is no true culture in America, only business and material production." But Ted isn't wrong – Barcelona was built on sales. The city was at the heart of Spain's industrial revolution, and all of those beautiful buildings designed by Puig, Luis Domenech, Antoni Gaudi and others were paid for by industrialists and bourgeois merchants made rich by sales.

(Something to remember for anyone sailing on the Steyn Cruise this winter, which departs from Barcelona. By all means take an architectural tour, but if you don't have time just go for a stroll on the Ramblas and stop for a drink at the Bar Boadas if it's open.)

In the meantime the anti-Americanism swirling about Ted and Fred has a body count; a bomb in the USO club kills a sailor and Fred is deputized to represent the Navy when his body is flown home. Along with a friend of the sailor, Ted and a bugle player playing "Taps", Fred reads the official service for burial at sea as a forklift in the airport warehouse picks up the coffin; it's as emotional as Stillman's decidedly dispassionate films ever get.

By the time I made it to Barcelona in the late '90s the bombings were mostly by ETA, Basque terrorists, like the Hipercor supermarket bombing in Barcelona that killed 21 people in 1987. In Stillman's film the cousins are constantly being asked about Americans being more violent, and at a party Fred is confronted by two women about shootings.

"Oh shootings, yes," Fred responds. "But that doesn't mean Americans are more violent than other people. We're just better shots." For some reason Europeans forget about their long history of political violence when accusing America of being a dangerous place; the logic is that political killings are just the cost you pay for European democracy.

The biggest antagonist the cousins encounter is Ramon (Pep Munné), an academic-turned-journalist and Montserrat's boyfriend, who can be found at parties insisting that even the killing of the sailor in the USO club was orchestrated by the Americans as a pretext for military action, a distraction to help the president during an election year. You can find someone like this anywhere (though back in the '80s and '90s they'd mostly be found on the left), but they were mainstream in Europe long before they had the same authority here.

Ramon, like Ted, has an obsession with beauty that has inspired him to sleep his way through the trade fair girls while writing popular columns about women in the newspaper. He had, apparently, read Philip Agee and become an expert on American covert activities. (One wonders if John Pilger was unavailable in translation at the time.) Thanks to Ramon Marta and her friends are sure that the American "AFL-CIA" and "Joey McCarthy" waged a campaign against communists in European labour unions after the war. Fred is sure this is wrong but has to check with Ted to make certain.

"It's amazing the things Americans don't know about their own country," Marta says.

But Fred's habitual lying inspires pillow talk hinting that he's working for the CIA. Marta passes this on to Ramon who identifies Fred as a CIA agent in a newspaper story, which in turn makes Fred a target for an attempted assassination that leaves him blind in one eye and in a coma. Ted keeps vigil at his bedside, enlisting trade fair girls to join him in shifts reading books like The Scarlet Pimpernel and War and Peace to the comatose Fred, hoping the sound of voices will bring him back.

This is a comedy, though, and it requires a happy ending, so not only does Fred emerge from his coma but he suffers a kind of memory loss that somehow excises the worst aspects of his character. Ted, certain throughout the whole movie that his job is in danger, meets with his immediate superior at the company, Dickie Taylor (Thomas Gibson), who tells him that he's being recalled to Chicago to help run the company, and that their boss didn't think Ted was meant to be a salesman. He hands him a copy of a book by management guru Peter Drucker, who becomes Ted's new guru. (Drucker emerged from business literature obscurity to become a major figure in the '90s, frequently writing for or being cited in WIRED magazine.)

Barcelona ends like any romantic comedy must with a wedding – a long scene where Ted is kept waiting at the altar by Greta (Hellena Schmied), one of the trade fair girls, and the only one who apparently never fell for Ramon's charm. While waiting for the bride in a bar Ted and Fred talk about anti-Americanism with the U.S. consul, who insists that it isn't as big a deal as everyone thinks. (Fred points to his missing eye and begs to disagree.)

The consul also revisits a hilariously bad analogy Ted had made earlier in the film, using red and black ants to describe communism and the "domino theory." The consul prefers to describe America as an ant farm, full of industry and complexity, except that "people who live in other countries can't observe the ants directly. They must rely on journalists and commentators for a description of everything going on inside."

"The problem," he concludes, "is that these people all seem to hate ants."

The film ends in the U.S., by the lake where the cousins summer, and where Ted and Fred have taken their Spanish wives (Fred marries Montserrat thanks to help from a contrite Ramon) and Dickie Taylor has ended up with Aurora. Earlier in the movie Ted had talked about how the American hamburger had become a stand-in for everything bad about America, but that hamburgers in Europe are inevitably terrible.

"Here, 'hamburguesas' are really bad," he says. "It's known that Americans like hamburgers, so again, we're idiots. But they have no idea how delicious hamburgers can be! But it's this ideal burger of memory we crave – not the disgusting imitations you get abroad."

At the lake Ted can grill the ideal hamburger and offer it to Greta and Montserrat, for whom it is apparently a revelation. Which ends Stillman's film on a triumphant note as beauty does not lead Ted and Fred to ruin, and the ideal burger does not disappoint.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.