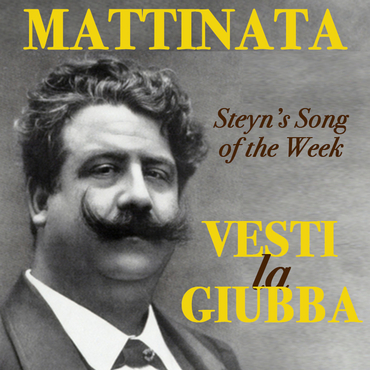

On this week's edition of Mark Steyn on the Town, we touched on a couple of connections between the operatic composer Ruggero Leoncavallo and the Anglo-American pop charts. And, as always, I got a flurry of responses from dissatisfied listeners saying they'd like to have heard a bit more about that, instead of me galloping on to the next record. Okay, here goes...

In August 1919 Signor Leoncavallo expired in the Tuscan town of Montecatini Terme. If you're in the neighborhood, don't bother looking for his grave. Three decades back they dug him up from the Porte Sante cemetery in Florence and moved him to Brissago in Switzerland on no greater say-so than a speech of his in 1904 in which he'd mentioned en passant that he wouldn't mind being buried there. There's nothing like a casual aside to trump your last will and testament.

Leoncavallo was a composer and librettist, and more admired as the latter than the former: by 1919, after the death the year before of Arrigo Boito (Verdi's Otello and Falstaff, Ponchielli's La Gioconda), Signor Leoncavallo was regarded as Italy's greatest librettist. On August 11th, his funeral was attended by almost all his most eminent musical compatriots, including Puccini, for whose Manon Lescaut he co-wrote the libretto, and Mascagni, with whose Cavalleria Rusticana Leoncavallo's most enduring opera has been paired in perpetuity. From that lasting work, here's Pavarotti with the big take-home tune:

Millions of people who profess not to know or like opera are aware of that aria. It has an indestructible memorability, if only because of its gimmick - the tormented laugh that separates the recitative (or the verse, in pop-song terms) from the chorus and is surely the most famous ha-ha-ha in music, even though it's set to no notes (unlike, say, "The Laughing Policeman"). But the gimmick wouldn't work were it not so right for the song's premise, which is the oldest showbiz conceit of all - even though your heart is breaking, the show must go on:

Vesti la giubba

E la faccia infarina...

Put on the costume and powder your face. Curtain up, light the lights, on you go.

The singer is a clown who heads a troupe of strolling players, among them his much younger bride Nedda. In the First Act finale of Leoncavallo's Pagliacci, Canio is preparing to take the stage in a commedia del'arte piece, in which he plays a man whose wife is cheating on him. Alas, back in real life, Canio has discovered that Nedda loves one of the villagers at their current touring stop. So, in the recitative, he tells us he doesn't know who he is anymore - a flesh-and-blood human being with real emotions, or just a stock stage character:

Bah! Sei tu forse un uom?

Tu se' Pagliaccio!

Bah! Are you a man? You're a clown!

So the show must go on, and the clown puts on the get-up and the makeup and prepares to yuk it up. The chorus reaches its emotional peak on the injunction "Ridi, Pagliaccio!" - or "Laugh, clown!" And it's the contrast between those two words and the wrenching five-note phrase to which they're set that makes the song. Leoncavallo's score provides the singer with a suggested line reading - "Tormented" - and, because the composer was also the librettist, the unity between words and music is greater than in many other operas, to the point where it's very hard to sing it in a non-tormented way. The sheet is full of interpretative instructions - "violently", "sobbing" - but, even without them, the number would be the emotional high point of Italian operatic verismo.

Leoncavallo had never written a completed opera before Pagliacci - and after its spectacular success he never wrote another hit opera. But, as much as for Meredith Willson with The Music Man or Lionel Bart with Oliver! or Jonathan Larson with Rent, with Pagliacci author and subject, words and music all came together as they never had before and never would again. In 1892 young Ruggero was no longer so young - a chap in his middle thirties who'd been a piano teacher for the brother of the Khedive of Egypt and then, following an uprising by the natives, an accompanist for café singers in Paris. But, aside from one symphonic poem, nothing he'd composed had made any impact, and his only attempted opera was Chatterton, a biotuner of the English poet who committed suicide at the age of eighteen. I mention that last fact because Leoncavallo had spent longer working on his life of Thomas Chatterton than poor old Chatterton had spent living it.

But in 1890 he had seen Pietro Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusticana and, impressed by its spectacular success, thought that he could do something in the same verismo style - if he just had the right libretto. How he came up with it is an interesting story somewhat simplified by RAF Bomber Command. In August of 1943 the chaps from Blighty blew Leoncavallo's publisher, Sonzogno, sky high, and did almost as much damage to the Teatro dal Verme, where Pagliacci was first performed. Which means that, in the absence of contemporaneous archival material, the most substantive version of the opera's creation is the author's autobiography. Thematically and to an extent musically, Pagliacci's treatment of infidelity, jealousy and murder owes a fairly obvious and explicit debt to the then new Otello and, from just a few years earlier, Carmen. But, as the composer liked to tell it, long before Messrs Verdi and Bizet, there was Ruggero's dear old dad, Vincenzo Leoncavallo, to whom the opera is dedicated.

The senior Signor Leoncavallo had been a magistrate in the town of Montalto Uffogo in Calabria, where Ruggero had passed his boyhood. On the night of March 5th 1865, just before the young lad's eighth birthday, there occurred a "tragedy that engraved in blood the memories of my distant childhood". A family servant, Gaetano Scavello, was murdered by two brothers, Giovanni and Luigi d'Alessandro, in a plot involving Gaetano's and Luigi's love of the same local maiden. One would have expected a judge whose servant is killed to recuse himself from the trial, but instead Vincenzo Leoncavallo presided over the investigation and conviction of the two perpetrators.

Pagliacci is set in the same town - Montalto - and in the same period - the late 1860s. But, of course, the stroke of genius is in taking this rather unexceptional crime passionel and relocating it in the world of showbusiness and commedia del'arte. No sooner had Pagliacci taken Europe by storm than the French author Catulle Mendès sued Leoncavallo for plagiarism for lifting the plot from M Mendès' one-act play of 1887, La Femme de Tabarin, which the composer could conceivably have seen when he was living in Paris. As someone who occasionally gets asked to weigh in on where-there's-a-hit-there's-a-writ suits, my advice is the easiest way to end the litigation is to assert that the chap who says you stole it from his earlier work himself stole it from some other chap's even earlier work. Which is what, in the end, Leoncavallo did: He argued that Mendès' La Femme de Tabarin was in fact plagiarized from Don Manuel Tamayo y Baus' Un Drama Nuevo of twenty years earlier. And lo and behold, the Frenchman's suit went away.

It's never the idea, it's always the treatment. And it's what Leoncavallo, as composer and librettist, did with the subject that made it a work for the ages. Yet Pagliacci's grip on posterity also benefited from a great technological marvel of the day: the wax cylinder. The opera's premiere - on May 21st 1892 - took place at the birth of recorded sound. A decade later, the most famous singer of his day, Enrico Caruso, made "Vesti la giubba" one of the first ever smash hit singles. There are, in the operatic repertoire, many popular tenor arias, but not all of them are suited to early gramophone records - for a very basic reason: They're too long. Leoncavallo's most popular number, however, happens to be short - short enough for wax cylinders and then for the 78rpm discs that replaced them. Caruso recorded "Vesti la giubba" thrice, in 1902, 1904 and 1907, and the last is calculated to be the first million-selling disc, although some scholars think a few copies of the earlier recordings may be bumping up those numbers. So to avoid disputes here he is with all of them:

On May 19th 1893, almost exactly a year after the Milan premiere, the first English production opened at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in a translation by F E Weatherly. As longtime readers know, I'm a big fan of Fred Weatherly, a barrister (and eventual King's Counsel) who dabbled very successfully in songwriting. His best known lyric is "Danny Boy", but I have a particular fondness for his beautiful song from the Great War, "Roses of Picardy", which I recorded in an epic bilingual version with my friend Monique Fauteux and which you can hear me tell the story of in a Song of the Week special here. In the comparatively journeyman field of operatic translation, Weatherly accomplished something most unusual with Pagliacci: He improved on the aria's title. He chose to render "Vesti la giubba" not as "Put on the costume" but as:

On with the motley.

Motley? Where'd that come from? Well, Shakespeare, insofar as anyone still used the term in 1893:

Motley is the only wear.

That's the Bard from As You Like It. "Motley" is a cognate of "medley" and possibly "mottled", and it's what a court jester wears - the multi-colored checkered garb that signals that the fool exists beyond social hierarchy in a category all his own. In commedia del'arte, it means the harlequin's patterned costume of red, green and blue diamonds. So Weatherly's title is far more specific than Leoncavallo's line, and it planted the phrase in the language - so that my callow teenage self used it in a song I was called upon to write at high school because "on with the motley" was the only thing I knew that rhymed with a proper name I had to get in there.

In 1931 Pagliacci became the first opera to be filmed as a talking picture - or, in fact, non-talking all-singing picture. Five years later, a second version was made by Trafalgar Films at Elstree Studios in Britain, this time using the Weatherly libretto. For some reason, despite filming it in English, they cast the great Austrian tenor Richard Tauber, who doesn't really get the full juice out of Fred's unusually fine text. That may not have been why the picture bombed, but to procure his services they'd agreed to pay him £60,000, which ensured that, when it did flop, it flopped at a staggeringly huge cost. Here's Tauber in full motley:

In the decades after its premiere, "Vesti la giubba" became surely one of the most parodied of all operatic arias: something about the premise (the clown going on with the show) and the treatment (the manic cackle) have made it an obvious target to less tragic clowns. See inter alia Spike Jones and his City Slickers and "Pal Yat Chee", which I couldn't honestly say has held up as well as other Spike Jones routines. Even more remarkably, beyond the spoofs and parodies, "Vesti la giubba" inspired almost a bona fide sub-genre of pop songs, in which the lovelorn swain sees himself as heartbroken clown, laughing on the outside, crying on the inside. At the Tamla Motown Christmas party in 1966, Stevie Wonder and his producer Hank Cosby brought along a tune they'd just written but couldn't think of a lyric for. They offered it to Smokey Robinson, who thought the jingly-jangly calliope figure in the fill was oddly circus-like. That in turn reminded him of a song he'd written a couple of years earlier called "My Smile Is Just a Frown (Turned Upside Down", which contained the couplet:

Just like Pagliacci did

I'll try to keep my sadness hid...

Which happened to fit the Stevie Wonder/Hank Cosby tune. And heigh-ho, "Tears of a Clown" was born. You'll notice that Smokey seems to assume "Pagliacci" is the guy's name rather than merely the plural of the Italian word for clowns. If one were going to use the stock figure the opera's character Canio plays, that would be "Pagliaccio", which is a kind of Italian equivalent of "Pierrot". In fact, Leoncavallo originally called his opera Il Pagliaccio - the clown, singular. The pluralization of the title came by way of request from a member of the original cast, Victor Maurel, who played the baritone clown Tonio and asked Leoncavallo to rename the show Pagliacci so that it would bulk up his own part and make it seem, if not the title role, at least one of them. It didn't. Instead, at least for anglophone lyricists, Pagliacci became the lead guy's moniker, now and forever:

Guess I'll have to play Pagliacci

Get myself a clown's disguise

And then learn how to cry like Pagliacci

With tears in my eyes...

That's by Herb Magidson, winner of the first Academy Award for Best Song, from a hit written a couple of years later with Allie Wrubel, composer of "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah". I get accused in this department of favoring too many recordings by Frank Sinatra, so, just for a change, here's Frank Sinatra Jr. As On the Town listeners heard yesterday, this is one of Frank Jr's best ever tracks, to a cracking Billy May chart commissioned by his dad that Pop never got around to - "The Masquerade is Over":

But the masquerade is never over. A century after the composer's death, Pagliacci remains one of the world's twenty most performed operas, usually in tandem with the verismo piece that inspired it - Cavalleria Rusticana: Cav & Pag, as the blockbuster double-act is known.

If that is his only lasting stage success, bestselling-record-wise the composer is not quite a one-hit wonder. In 1904, fresh off the success of "Vesti la giubba" on disc, Leoncavallo became the first writer to create a song specifically for a record label - the Gramophone Company (now EMI). It was a lovely flowing melody called "Mattinata" - or "Morning". Here's the voice Leoncavallo wrote it for - Enrico Caruso, in this song's very first recording, and with the composer himself at the piano:

"Mattinata" quickly became (and remains) a tenor favorite. The theme is daybreak - "The dawn opens the door to the sun," as the lyric begins - and it suits the tune. But the vagaries of American copyright law turned it into something entirely different in English. In Italy, in Europe, in the British Commonwealth, the expiration of copyright depends on the creator's date of death. But not, until recently, in America. Instead, in US law, there was a twenty-eight-year term from the date of publication, which could be renewed for a second twenty-eight-year term, if you happened to notice expiry was coming up and remembered to apply for it. As a result (and quite disgracefully), many long-lived writers managed to outlive the copyright of their early hits - as Irving Berlin did with "Alexander's Ragtime Band". In the case of Leoncavallo, by the 1940s "Mattinata" had fallen into public domain in the US, which diminished status came to the attention of Pat Genaro and Sunny Skylar, a couple of opportunist Tin Pan Alleymen in need of a good tune. I don't know much about Mr Genaro, but Skylar was a canny fellow who gave us a song I've always been partial to, "Gotta Be This or That" (with the memorable line "If it's not Bing, it's Frank"), as well as "It Must Be Jelly ('Cause Jam Don't Shake Like That)" and the English lyric to "Bésame Mucho". Genaro and Skylar put an utterly pedestrian text to "Mattinata", but Leoncavallo's tune is so glorious that exactly seventy-five summers ago Buddy Clark, the Ink Spots, Ralph Flanagan, Jan Garber and Russ Case all got into the Billboard Top Thirty with it - and in September 1949 Vic Damone hit Number One:

So Leoncavallo wound up a two-hit wonder, with both hits being about broken hearts: "Vesti la giubba" is the gut-wrenching ache of a man seriously cracking up, and "You're Breaking My Heart" sounds like the chap'll be over it by lunchtime. Still, for a while an inordinate number of singers loved "You're Breaking My Heart". A generation on from Vic Damone, Keely Smith recorded it in a version produced by her then husband. Jimmy Bowen did for Leoncavallo what he did for Dean Martin with "Everybody Loves Somebody": He took a conventional ballad, and backed it with drums and insistent triplets in the piano that gave it just a frisson of rock'n'roll. It was enough to get Keely to Number Fourteen in the UK Top Twenty in 1965:

I doubt Leoncavallo would have cared for that arrangement, but you never know: Try and imagine it with the piano part replaced by Canio the pagliaccio instead going ha-ha-ha ha-ha-ha underneath Keely for three minutes. That's Ruggero Leoncavallo: one man, two hits, and heartbreak all the way.

~Steyn tells the story of many beloved songs - including the above-mentioned "Roses of Picardy" - in his book A Song For The Season. Personally autographed copies are exclusively available from the Steyn store - and, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter the promo code at checkout to enjoy special Steyn Club member pricing.

The Mark Steyn Club is now in its eighth year. As we always say, club membership isn't for everybody, but it helps keep all our content out there for everybody, in print, audio, video, on everything from civilisational collapse to our Sunday song selections. And we're proud to say that thanks to the Steyn Club this site now offers more free content than ever before in our twenty-one-year history.

What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, it's an audio Book of the Month Club - tonight's installment of our latest yarn will air in a couple of hours - and a video poetry circle, and a live music club. We don't (yet) have a clubhouse, but we do have other benefits, and, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of all that and more, we also have a special Gift Membership. More details here.