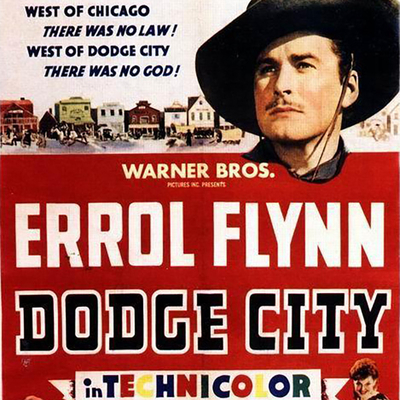

A lot of people were dubious about Warner Bros. casting Errol Flynn in his first western, Dodge City, among them Errol Flynn. Writing in his autobiography My Wicked, Wicked Ways, Flynn said that "I felt I was mis-cast in Westerns, but this was impossible to point out to producers when the pictures were so highly successful."

"It was most frustrating," the actor went on, "it stopped my trying to act. I walked through my roles, jumped on that old horse, swung my legs over that old corral fence. My heart wasn't in it, only my limbs."

This might have been true with Flynn's subsequent westerns – films like Virginia City, Santa Fe Trail, They Died with Their Boots On, San Antonio, Silver River, Montana and Rocky Mountain – but it's possible to discern Flynn still making an effort in Dodge City, though he rarely liked to let audiences think that any role made him break a sweat.

Because while Dodge City was hardly the first western Hollywood made, it was among the first of a new type of western – the big-budget, star-studded epic where every abundant dollar is on the screen, made with the top talent on the studio's roster. It set in stone all the tropes and standards that would define the Hollywood western for at least a decade and set up every target that revisionist westerns (which is to say almost every notable western since the '50s) would try to knock down.

After the credits roll over Max Steiner's score, a title card informs us that the Civil War is now over and "the nation turns to the building of the west." A steam engine rumbles along a single track across the prairie and the camera alights on its passengers – a group of rich men drinking in a luxury train car, among them Colonel Dodge (Henry O'Neill), the man who built this railroad.

Its terminus – at least for now – is a new town in Kansas at the end of the trail for cattle drovers who need to get their livestock to places like Chicago. The film wants us to believe that Col. Dodge hadn't given any thought to what to name this town, and he half-reluctantly agrees to a suggestion given by one of the men who helped him build the railway, Wade Hatton (Flynn), that he name it after himself.

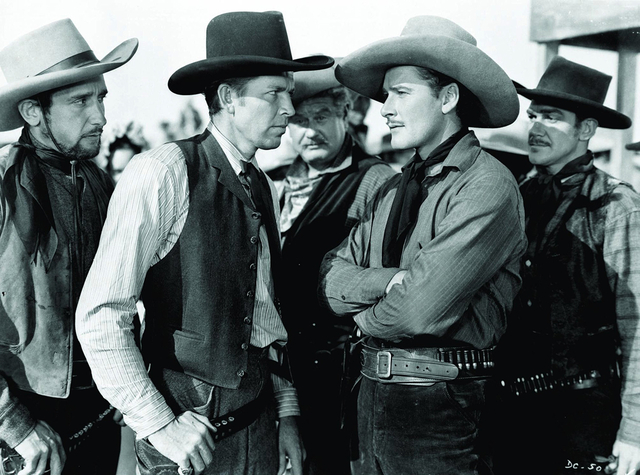

Wade had made himself useful to Dodge by hunting buffalo to provide food for the workers building the railroad, helped by not one but two comic sidekicks – Rusty (Alan Hale Sr.) and Tex (Guinn "Big Boy" Williams). He's made influential friends like Dodge, but also enemies like Surrett (Bruce Cabot), who we meet when Wade brings a posse of lawmen to intercept Surrett and his men with a wagon train full of buffalo hides; they'd poached the animals for their skins, leaving the carcasses to rot on the prairie, shooting the Indians who'd protested at wasting animals and breaking the law.

"Often, in these pictures, I had to alibi my accent," Flynn wrote in his autobiography, "which was still a bit too English for the American ear." In Dodge City the alibi is provided by Hale's Rusty, who explains Wade's backstory – an Englishman who soldiered in India, ended up in Cuba for some sort of revolution before doing some cattle punching in Texas. They met when he ended up fighting in the Civil War on the Confederate side – a detail audiences in 1939 were expected to allow without rancour, but it was the year when Gone With the Wind was released, after all.

It sketches in Flynn's Wade as exactly the sort of jolly rogue and adventurer that audiences wanted to see, whether in tights or buckskin, and which Flynn was more than happy to imagine in himself. Because it has to be understood that Flynn was a very, very big star when he made Dodge City – one of Hollywood's biggest, and a headache for studio boss Jack Warner, who had to run damage control on the actor's scandalous private life as well as escapades like the one that took him to Spain during their Civil War.

In his autobiography Flynn insisted that "I decided that since the split was a revolution by Franco against the legally elected Republican Government, then I leaned toward the Left. There might be a little more idealism and humanity on that side." Flynn wrote this in 1959, before journalist George Seldes claimed that Flynn's trip to Spain was a cheap publicity stunt, and before Charles Higham claimed in a notorious 1980 biography of the actor that, far from being a Republican supporter, Flynn was actually a bisexual fascist sympathizer, based on evidence he was never able to produce and protested adamantly by Flynn's family and friends, including David Niven, Olivia de Havilland and Iron Eyes Cody.

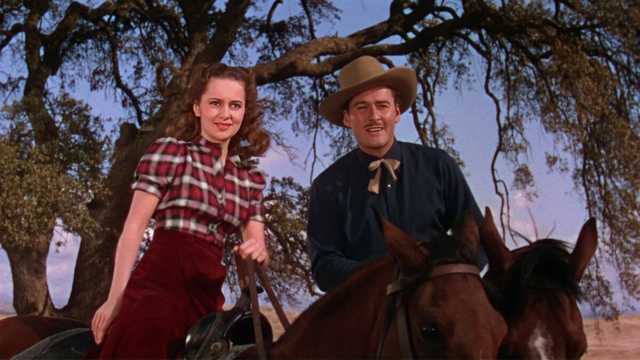

Wade makes another enemy when he leads a group of settlers on a cattle drive to Dodge City, including the niece and nephew of the town doctor – Abbie Irving (de Havilland) and her irresponsible tearaway brother Lee (William Lundigan). The young man is a drunkard fond of firing his revolver to relieve the boredom of the journey; he antagonizes Wade and tries to shoot him, earning a bullet in his leg before the gunshots cause a stampede that tramples the idiot lad to death.

Abbie blames Wade for his death even though her uncle accepts his explanation and forgives him. This would be exactly what fans of Flynn expected, as his onscreen dynamic with de Havilland since they were cast together for the first time in Captain Blood was fueled by a love/hate relationship that resolves itself before the third act. Formulas that tested well with audiences became sacred to the studios, and both Flynn and de Havilland were trapped together by theirs as it helped make them both stars.

"How could I know how Olivia de Havilland felt about having to be my leading lady?" Flynn wrote later. "How could I know what went on in her mind? – that she was sick to death of playing 'the girl' and badly wanted a few good roles to show herself and the world that she was a fine actress? And how could she know that I wanted to do something really creative?"

When Wade returns to Dodge City he discovers that the promising little town has boomed, but it's also become a lawless hellhole run by Surrett from his saloon, a law unto himself who can get away with killing a cattle agent who demands money he's owed, then run the sheriff out of town when he tries to serve a warrant, bundling the lawman into the same hearse that had carried the cattle agent to the cemetery.

You only have to squint a little to recognize that Dodge City is based very loosely on the legend of Wyatt Earp, with names changed and details fudged. But this will only bother you if you've forgotten that every other movie version of the story of Earp and his brothers, Doc Holliday and the gunfight in Tombstone, from Law and Order (1932), the first cinematic re-telling, through My Darling Clementine (1946) to Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957) to Hour of the Gun (1967) to Doc (1971) to Tombstone (1993) to Wyatt Earp (1994) has taken wide liberties with a story that was already transformed into a legend while most of the participants were still alive.

It's all there – the simmering war between cattlemen and "cowboys", the frontier town struggling to overcome anarchy and calm the fears of financial backers out east, and the residual tension between men who had only recently fought for the Union or the Confederacy, which erupts in Dodge City into a huge, largely comic brawl in Surrett's saloon when Tex and the drovers provoke Surrett's men, led by the nefarious Yancy (Victor Jory), by singing "Dixie" to drown out a version of "Marching Through Georgia" performed by saloon chanteuse and Surrett's main girl Ruby (Ann Sheridan).

Sheridan had already had a long career since she got her first movie role in 1934 – an impressively dispiriting list of walk-ons and bit parts before she made her first big splash in Angels with Dirty Faces (1938). Warners decided to market her as the "Oomph Girl" – a moniker she hated, with good reason – and she suffered with this until better roles came along in They Drive By Night (1940), The Man Who Came to Dinner and Kings Row (both 1942).

She's badly wasted in Dodge City, performing a couple of musical numbers on the stage of Surrett's saloon and having a table collapse beneath her during the big brawl before effectively disappearing from the picture.

Wade turns down the town's offer of a job as the new sheriff until a little boy, the son of the cattle agent murdered on Surrett's orders, is killed during one of the gun battles in broad daylight on the town's main street. He straps on the badge, deputizes Rusty and his drovers, and begins throwing Dodge City's lawless element into jail; he even issues an order proclaiming that collection of taxes will be enforced.

This puts him on a collision course with Surrett, whose gunmen can't get a drop on Wade so he starts targeting people around him, like Abbie and the publisher of the town's newspaper, who gets shot in the back by Yancy. Wade throws Yancy in jail but can't stop the lynch mob that forms outside, eager to take rough justice. So he sneaks him onto the train to Wichita and the closest thing to law and civilization – the same train that he'd persuaded Abbie to take for her own protection. When Surrett and his men hijack the train they start a gun battle with Wade and Rusty in the baggage car – one of those shoot-outs where revolvers are loaded with endless rounds of ammunition.

The baggage car gets set on fire, Abbie is taken hostage, and the locomotive pulling its flaming carriage hurtles down the track while Wade and Rusty try to escape certain death and deal with Surrett and his henchmen before they can escape. It's loud, wild, improbable and thrilling stuff, made all the more so by Michael Curtiz' typically kinetic direction.

In The Encyclopedia of the Western Movie, Phil Hardy calls Dodge City "a sprawling epic with Flynn, in fine swashbuckling form, taming the West and de Havilland." He compares it to John Ford's version of the Earp story in My Darling Clementine, noting that "for Ford this is represented by a series of cultural rituals (Shakespeare, perfume, the dance and the church) overlaying the almost Biblical confrontation of the Clantons and the Earps, for Curtiz ... 'Civilization' means organization: the railroad, gangsterism, the press. Ford looks on with mixed feelings, Curtiz with an eye to the urban future."

Warners put big money into Dodge City thanks to the critical and box office success of another Ford western, Stagecoach, earlier that year, but it was shot in lush, vivid three-strip Technicolor, like those two other movie landmarks of 1939 – Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz. It's redolent of backlot and soundstage, but what film made around that time isn't?

No, what makes this landmark western feel more dated than, say, Ford's film is how that eye-popping colour captures the costumes and sets in Curtiz' film. This is the Hollywood Western at its most artificial, where the buckskins and gingham seem a little too crisp, and no one looks dusty, sweaty or scarred unless they've been dragged behind horses or trampled by cattle.

Jack Warner set his studio's publicity machine to work, organizing a massive gala premiere of the picture in its namesake town – the sort of spectacle guaranteed to blare from newsreels and newsprint.

"While I couldn't understand the public buying me particularly," Flynn wrote in My Wicked, Wicked Ways, "I could understand the Western, the frontier story, as a classic form of national entertainment. It is part of America's heritage, our history. Everybody knows what a Western is about. The title would be enough to tell you, expressive, simple, native, like Stagecoach."

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.