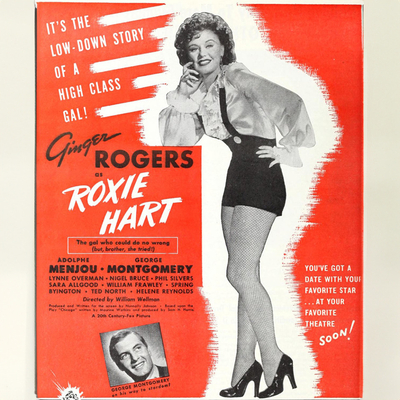

When William Wellman's comedy Roxie Hart was released in February of 1942, it joined what would become a long list of films panned by New York Times movie critic Bosley Crowther, who called it "a lot of coarse nonsense" and "simply a ribald wallow in the cheapness of an ugly phase of life."

He acknowledged (and yet somehow diminished) the talent of its star, Ginger Rogers, as "a most credible Miss Twinkle-Toes", as well as Adolph Menjou and the rest of the "supporting cast of able harlequins" who, along with Wellman and producer Nunnally Johnson, "have knocked together a rowdy and brassy burlesque." But despite their best efforts, Crowther judged the film "a raucous and tasteless travesty."

Twenty-five years later Crowther panned another period picture in the Times as "a cheap piece of bald-faced slapstick comedy," a "strangely antique, sentimental claptrap" and one that "is as pointless as it is lacking in taste, since it makes no valid commentary upon the already travestied truth."

The sharp-eyed will recall that the film this time around was Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde, and that Crowther's opinion – expressed not just in this review but two subsequent ones and in asides in further columns – effectively spelled the end of his long tenure at the Times. Crowther was semi-retired that year, assigned to the Roving Reporter desk as "critic emeritus" before he got the message and left the paper.

Bosley Crowther is remembered as a cautionary tale in newspaper criticism – the tragic tale of a man who lost his relevance and ability to judge the tenor of the times. His name alone suggests a fustiness evoking sleeve garters and detachable collars and cuffs – or did, back when there were enough people alive who could remember anyone wearing such things.

This is mostly unfair, a by-product of a campaign waged against him by younger critics (Pauline Kael, Richard Schickel, Molly Haskell, Andrew Sarris) who needed to discredit Crowther to show their support for Bonnie and Clyde. In his time, Crowther was outspoken in his support of all the Right Things – against censorship and the Production Code, an opponent of the blacklist, HUAC and McCarthy and an early champion of European filmmakers like Bergman, Fellini, De Sica and Rossellini.

But he expressed his opinions with rhetoric that might have been only slightly sententious when Roxie Hart was released, but which sounded unforgivably moralizing by the '60s. His tone was, as his 1981 Times obituary put it, "scholarly rather than breezy", and he could be prescriptive in his expectations of not just filmmakers but audiences. The result was that his take on a film like Wellman's came across like the sour and opinionated older relative at a holiday dinner.

Rogers is the titular Roxie, a coarse but ambitious chorine who ends up on trial when her theatrical agent is found shot dead on the floor of her bedroom. Though as much as that it's a Chicago story, set in that most American of cities, where gangsters and corrupt politicians dominate the front pages when there isn't a high-profile murder case competing for public attention.

But we meet Roxie in a flashback, told from the perspective of Homer (George Montgomery), a veteran reporter who regales the late-night crowd in a bar with the story of Roxie, the greatest story he ever covered, back when he was a rookie reporter under the wing of Jake Callahan (Lynne Overman). It's been fifteen years since Roxie's case exploded across the headlines and Homer swears it was a better time – or at least the murders were more newsworthy than the banal one he and cub reporter Stuart (Ted North) were called to cover across the street.

Roxie's case was shaping up to be ho-hum homicide until Callahan spies Roxy sneaking back into the apartment from the fire escape after her husband Amos (George Chandler) takes the rap. He locks her in a closet before getting her to go along with his headline-grabbing scheme – that she'll confess to murdering her handsy, lust-crazed agent to spare Amos and (more importantly) goose her career with some priceless publicity since, as Callahan points out, Cook County goes easy on female murderers (revealed to the audience in a montage of murderesses on front pages just after the opening credits roll.)

"This county wouldn't hang Lucrezia Borgia," he says confidently.

Roxie Hart's story is based on the true story of Beulah May Annan, the wife of a car mechanic who shot her boyfriend Harry Kalstedt and sat finishing off the bottle of wine he'd brought over, playing a record, "Hula Lou", over and over on her gramophone while waiting for him to die. Or at least that was one version of the story she told. Maureen Dallas Watkins, a Chicago Tribune reporter who covered the story, combined Beulah's story with that of another murderess, Belva Gaertner, a cabaret singer who killed her lover while drinking in her car.

Watkins transformed Beulah and Belvah into Roxie and Velma, jailhouse rivals and clients of Billy Flynn, a flamboyant trial lawyer who claims he has never lost a case where a woman killed a man. She made Roxie the (anti-)heroine of her play, Chicago, which was made into a movie in 1927, produced by Cecil B. DeMille.

Dancer Gwen Verdon was a fan of Chicago and she and her husband Bob Fosse spent years begging Watkins to allow them to produce a musical adaptation with Verdon as Roxie. She turned them down until her death, when her estate finally sold them the rights. With music and lyrics by John Kander and Fred Ebb, it was a decent hit in 1975 but an even bigger one with its 1996 revival. It remains a hot property, constantly revived, and a keystone of Fosse's legacy.

In 2002 choreographer Rob Marshall made his directing debut with a film adaptation of Chicago starring Renee Zellweger as Roxie, Catherine Zeta-Jones as Velma and Richard Gere as Billy Flynn. A massive hit, it was nominated for thirteen Oscars and won six, and along with 8 Mile, Hedwig and the Angry Inch and Moulin Rouge! comprised one of those sporadic resurgences of the movie musical that never seem to really revive the genre.

One of the major differences between Wellman's Roxie Hart and the other versions is that Rogers' Roxie isn't guilty, but she agrees to take the blame in exchange for headlines and a boost to her going-nowhere career. (In real life it doesn't appear that Beulah Annan had any theatrical ambitions whatsoever when she pulled the trigger.)

This presents us with that uniquely Hollywood spectacle: a very talented star playing a putatively untalented nobody. Wellman's film naturally gives Rogers some showcase numbers, including a jailhouse demonstration for the press doing her "Black Hula" (a combination of the Black Bottom and a Hawaiian hula – a nod to the disc on Beulah's Victrola the night of the murder) and a tap routine that Roxie improvises on the metal stairs of the jailhouse – probably one of Rogers' onscreen highlights as a dancer.

In Wellman's film Velma is played by Helene Reynolds and reduced to a single scene that ends in a catfight between Roxie and Velma. While Chicago's story relied on a rivalry that ended up putting whoever played Roxie and Velma at the top of the bill, Roxie Hart is very much a star vehicle, based around Rogers' talent and very particular appeal as a comic heroine.

Even partnered with Astaire, Rogers projected self-sufficiency and a toughness that challenged her whenever she had to play – or pretend to play – a society type. Writing about Rogers in Kitty Foyle (1940) in his book Romantic Comedy in Hollywood from Lubitsch to Sturges, James Harvey says that "we may expect to see other stars with the Una Merkel kind of sidekick or girlfriend, but for Rogers such a companion would be superfluous. She is her own sidekick."

Our certain knowledge of that actual talent is crucial to Wellman's film, because his Roxie – like all the other Roxies – is an essentially amoral creature, motivated by self-interest, capable of any betrayal or perjury. The only balance is that this is true of nearly every other character who isn't an utter dolt (like her husband Amos), and even if justice isn't served and truth doesn't out, there's something like (but not the same as) redemption in Roxie winning the debased prize of her turn in the spotlight.

Marshall's movie adaptation of Fosse's play tries hardest to make Roxie pathetic and, ultimately, sympathetic, but that was never supposed to work. Wellman's film is actually the most pitiless and Rogers' Roxie is relentlessly fixed on her prize – at least until the twist ending.

She's a user, but she's an amateur compared to everyone around her, from cynical hacks like Callahan to Menjou's utterly mercenary Billy Flynn. The most famous number in Marshall's film has Gere's Flynn play the puppet master, pulling the strings of everyone from Roxie to journalists like Christine Baransky's sob sister Mary Sunshine and the rest of the press corps. But in Wellman's film the whole idea of getting Roxie to confess is cooked up by Callahan and his reporter buddies before Flynn has a chance to take her case.

"We're supposed to make up a story," Callahan tells Chapman, "not tear it down."

Sixty years later audiences had no problem accepting a vision of a puppet media, dutifully repeating what they've been fed by people like Billy Flynn, while Wellman's reporters are more of a semi-feral pack, searching for angles on their own when people like Flynn can't be bothered to provide them. I wonder what might have changed in those six decades?

There's a screwball tone to Wellman's picture, especially whenever Roxy is presented to the press. Her "Black Hula" number turns into an anarchic production number with reporters and photographers dancing on chairs and tables like Charlie Brown's gang in the famous Christmas special.

Best of all are the press photographers with their big cameras and flash bulbs, led by Phil Silvers' Babe, their ringleader. He marshals them into place while stage directing everyone from Roxie and Flynn to the judge, breaking up the tableaux by barking "That did it!" after the flash bulbs pop. The prison matron breaks up the fight between Roxie and Velma by knocking their heads together; Amos paces the corridors of the jail complaining hopelessly that he can't get in to see his wife, while a prison screw ignores him studiously.

Play-by-play at the trial is provided by a dog-faced radio reporter with a British accent, balefully repeating the slogans of his quack medicine sponsor between colour commentary. And the all-male jury bends and cranes their necks as one every time Roxie lifts her hem or crosses her legs, while Menjou chews the scenery presenting his farcical interpretation of a legal defense, perfectly suited to his venue.

Unlike lightweight cities like New York or Los Angeles, Chicago is a red-blooded American town where "murder is entertainment," he says.

"In Chicago, the law doesn't count. It's justice we're after."

Ultimately Roxie Hart has more in common with a cartoon than any mere comedy. It plays like a product of Warner Bros.' Termite Terrace, at a similar breakneck pace, and it's hard not to imagine every character voiced by Mel Blanc, with Porky Pig as Amos, Bugs Bunny as Callahan and Daffy Duck (or, even better, Foghorn Leghorn) as Billy Flynn. And the jury box would be filled with leering wolves in pinstripe suits.

I'm sure this is what bothered Crowther the most about Wellman's picture – a fundamental unseriousness about what he considered serious issues, set during a period of history that should have been depicted with critical disapproval. It's the same irritation he would show twenty-five years later when presented with Arthur Penn's amoral "youthquake" version of the story of a pair of thrill-killers he remembered more acutely, and not as either sexy or romantic.

But while Wellman and Nunnally Johnson were free to make Crowther cross, they couldn't afford to take too may liberties with the Production Code, which is why – unique among versions of Watkins' story of Roxie and Velma – Rogers' Roxie isn't a killer. (A murderer simply wasn't allowed to escape justice for their actions in a world overseen by Joseph Breen.)

And it explains the film's ending, which doesn't end with Roxie triumphant onstage, either with or without Velma as a partner. Viewers might have noticed the resemblance between the jury foreman and O'Malley, the bartender in the dive where Homer is holding court with his stories of Roxie's trial, and his own abject youthful infatuation with the accused murderer.

They are, of course, the same man (played by William Frawley – Fred Mertz in I Love Lucy), though he was a stockbroker when he asked Roxie to dinner in his Packard after her acquittal, leaving us in Homer's story with a cliffhanger whether she'd choose the adoring cub reporter or the rich older man.

But Homer hasn't forgotten and asks O'Malley what happened to the Packard as he leaves. Gone with everything else in the stock market crash, he says. Outside the bar it's a rainy night and Homer admits that he's two hours late meeting his wife, just as a little black coupe pulls up to the curb.

Inside it's Roxie at the wheel with a half dozen kiddies who Homer has to rearrange to get into the passenger seat just as his wife says she has some news – that they're going to need a bigger car. The smile that plays across Rogers' face as she pulls into traffic lets us know that this is a real happy ending and not an ironic one – not in 1942, and not at 20th Century Fox. Perhaps this is what put Bosley Crowther into such a bad mood while reviewing Roxie Hart, though it wouldn't make him any less cross years later, when he had to write about the first film truly made in a world without the hated Code.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.