"Dead men tell no tales," writes Nicholas Christopher in Somewhere in the Night: Film Noir and the American City, "but not in film noir, where the hero may narrate his own tale, fluently, from the grave." This is certainly true of classics of the genre – D.O.A., Double Indemnity and, to some degree, Out of the Past, but most famously of all in Billy Wilder's Sunset Boulevard. Take a good look around when each character is introduced, we learn, because a lot of them won't be around at the end – particularly the putative hero, who may already be a goner.

When this became a trope is up for debate, because no one can say for certain when the first person sat down in a movie theatre pumped up to take in a film noir. Sure, the term was coined in 1946 by Nino Frank, a French film critic, but who was really listening to the French at that point? What there was, sprawling across police procedurals, melodramas, thrillers, detective stories, boxing pictures and gangster films for the next decade was a free-floating mood – a sort of post-war malaise that, after a while, you knew when you saw it.

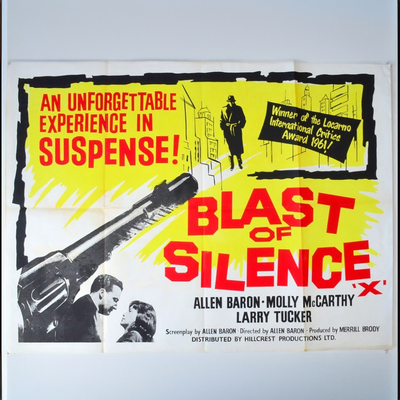

I guess the term finally stuck when the French started exporting noir back to America, with films like Jean-Pierre Melville's Bob le flambeur (1955), Louis Malle's Elevator to the Gallows (1958) and especially Francois Truffaut's Shoot the Piano Player and Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless (both 1960). It was definitely taxonomized by the time Allen Baron's ultra-low budget Blast of Silence was released in 1961 – a noir that had achieved self-consciousness.

The film begins in darkness – what the narrator refers to as the "black silence" from which our protagonist was born: one "baby boy Frankie Bono" as the voice calls him, "out of Cleveland." The darkness is a tunnel, and we're with Frankie on a train to Penn Station, where our hero, a hitman, has traveled for a job. We get a few tantalizing shots of the grand train station, itself only two years away from its own demise, though it seems certain that the building will outlive Frankie, whose impending expiry date is more than inferred by the narrator's insolent tone.

That voice isn't Frankie's but something rarer – a "second person" narrator who has almost divine knowledge of Frankie's past and thoughts. The narration was the product of two blacklist victims: writer Waldo Salt and actor Lionel Stander. Stander's career went back to the '30s and roles in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and the Janet Gaynor/Frederic March A Star is Born; he was a hostile witness when he testified in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee and moved to Europe, where among other roles he played the bartender in Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West. When he returned to America he appeared in New York, New York and 1941, but many people will remember him as Max, the gravel-voiced sidekick to Robert Wagner and Stephanie Powers in the TV series Hart to Hart.

Salt began his career with the script for The Shopworn Angel (1938), and when he refused to testify in front of HUAC he ended up writing TV scripts in Britain. His return to Hollywood was hardly inconspicuous: he wrote the scripts for Serpico, The Day of the Locust, Midnight Cowboy and Coming Home, winning Oscars for the last two. (The blacklist could be a catastrophe for many of its victims, but for others it was merely an interruption or a change of venue; in Salt's case his post-blacklist career was actually a triumph.)

Salt's narration, delivered by Stander, wastes no time getting to the point. "You were born in pain," he tells Frankie, and the soundtrack obliges with an aural montage – a woman's gasps of agony, a baby crying. There's a distant, probably absent father, and an unhappy childhood that prepared the ground for what Frankie is today, on this day, as he arrives for the job – a hired killer.

Frankie was supposed to be played by Peter Falk, a friend of Baron's from summer stock, but Falk got a role in Murder Inc., so Baron was forced to cast himself. "I was the only actor I could afford," he said later. Baron is suitably cold and emotionally removed as Frankie, who considers himself the consummate professional, setting about his job precisely, with an eye for detail. The narrator tells us that – at least in his own mind – he could have been an engineer or an architect.

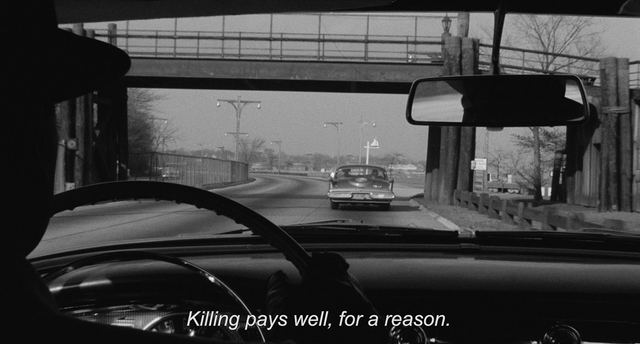

It's up to us to decide of Frankie's assessment of himself is accurate or delusional, but Stander's delivery is too mocking to make anything but the latter plausible. But we watch Frankie go about his deadly business while the narrator informs us what he's thinking every step – checking into a hotel, meeting his contact from the New York mob on the Staten Island Ferry, who reveals the identity of his intended victim: Troiano (Peter H. Clune), a mid-level local mobster whose ambition has become a liability for his superiors.

Frankie sets about tailing Troiano and his security goons as he goes about his errands, changing cars every day to avoid being spotted, knocking off when he has Troiano's schedule down, looking for the moment in his daily routine when he's alone and vulnerable. All the while he begins to hate his quarry, an apparently necessary preliminary to ending his life, according to the narrator, who also wants us to know that Frankie is a very damaged soul.

What makes everything worse for Frankie is that it's Christmas in New York, the time of year when the city presents its best face, but it only ramps up the background hum of discomfort for the hit man – the "scream" the narrator tells us is always building up in Frankie's head. Working with no other emotion but clinical hatred in play has always worked for Frankie, but he's confronted with old memories that disturb his precious equilibrium.

The biggest problem with being a hit man – for Frankie at least – is apparently other people; the victim, of course, but also clients and middlemen and suppliers, like Big Ralph (Larry Tucker), an old but despised acquaintance who he contacts to get him the gun and silencer he needs to complete the job. Morbidly obese and personally repulsive – he keeps sewer rats as pets (sewers are a metaphor that recur in Salt's narration) – he's the sort of low-life hanger-on that Frankie, with an inflated sense of his professional dignity, regards with undisguised contempt.

Whether tailing Troiano or killing time waiting for the gun, Frankie takes us on an indelible tour of Manhattan as it looked at the end of the '50s – a well-worn but still functional city, from Rockefeller Center and Harlem to the Village and the riverfront and the apparently endless streets of midtown, straight lines stretching across Manhattan to a vanishing point of empty sky. (In a tour of the film's locations made in 2006 and included in the Criterion reissue of the film, Baron returns to New York and is surprised to find that those bleak streets are now lined with trees – the intervening years were rough on New York, but in some instances it has come out the other side improved.)

Most distressing of all, Frankie crosses paths with Petey (Danny Meehan), an old friend from the orphanage where they were raised, who insists he come to a Christmas party being thrown by his sister Lorrie (Molly McCarthy) in the beatnik Village. Their offer of friendship is more unsettling than his intention to make Troiano's wife a widow; moved by an urge he can't understand he accepts Lorrie's invitation to Christmas, but her tentative flirtation with him only provokes a sexual assault.

He's immediately overcome with regret and shame but attempts to explain himself and articulate emotions he's unaccustomed to expressing involve Baron going from sullen to angry with very little in between. It's at this point that an informed viewer might miss Falk, who would have found the modulation necessary to bring the scene home. But the point is made nonetheless: Frankie is as lost with the niceties of basic human interaction as he's at home planning a man's murder. ("If you want a woman, buy one," Stander's narrator explains. "In the dark, so she won't remember your face.")

The city, as Nicholas Christopher writes in Somewhere in the Night, is "a labyrinth ... a veritable icebox morally and in which violence provides the only emotional relief."

Frankie is at his best as a ghost trailing in Troiano's wake, observing him from every possible vantage point from driver's seat to rooftop, letting himself into the apartment he keeps for trysts with his mistress, silently measuring the place and taking the measure of his quarry. If only he didn't have to follow it through to the only conclusion – the killing that has to happen to give everything else purpose.

And it's people who spoil everything – in this case Big Ralph, who happens to be in Art D'Lugoff's Village Gate (real locations were used in the movie in almost every instance except apartment interiors) when Frankie tails Troiano and his mistress there for his birthday party. Realising who Frankie intends to kill with the gun he's procuring for him, Ralph decides that this kind of "big game" boosts the weapon's price.

He follows Frankie into the bathroom to threaten him while the camera cuts back and forth to the club's headline act – a conga player and singer (Dean Sheldon) who does outrageous calypso takes on murder ballads. (It's the only time the film's visuals match the overcooked tone of Salt's narration.) Rattled, Frankie follows Ralphie home and is about to do him in with a fire axe when the big man suddenly wakes up.

The ensuing brawl trashes Ralph's apartment – rats set loose everywhere; how's that for a metaphor writ large – before Frankie can finish him off, but the body and the headlines ("HOODLUM STRANGLED" blaring across the morning papers) threaten what was supposed to be a clockwork hit, and Frankie tries and fails to back out of the contract.

As Terrence Rafferty writes in the essay included with the Criterion reissue, Blast of Silence might be "hands down, the best movie ever made about a common, important and unjustly neglected American experience: the really bad business trip."

Allen Baron was born in Brooklyn in 1927 to a working class family, and came of age during what was probably the golden age of social mobility in America. After graduating from the School of Visual Art he worked as a comic book artist before a visit to an empty Paramount soundstage inspired him to change careers for the movies.

He claims that he acquired the equipment necessary to make Blast of Silence after working on Cuban Rebel Girls, Errol Flynn's final film. The production had abandoned their gear when the Fidel Castro's revolution broke out, and the producers agreed to let him use the equipment if he could return to the country and smuggle it back home. The decision to get Salt to write the narration was made after the film was shot, but it was a brilliant one as it freed Baron from using sync sound for everything but a few crucial interior scenes.

After Eastman Kodak gifted him with a roll of experimental film stock to try out, he raised the money necessary to shoot and develop his screen test, which ended up being used in his film. He got his lab to defer payment for processing and with a sudden windfall from unexpected angel investors managed to shoot Blast of Silence in just over three weeks, filming the finale during a hurricane, throwing himself into the chilly waters of Jamaica Bay. After he discovered they were one actor short, he put himself in a shot, chasing himself through the now-gone fishing village in what's now Spring Creek Park.

It's hard to account for the confidence with which Baron completed his first movie. There are a few examples of directors who made a single film upon which their reputation rests; the most notable is actor Charles Laughton, whose Night of the Hunter flopped but is now considered an undeniable classic. There's also Barbara Loden's Wanda (1970) and Herk Harvey's Carnival of Souls (1962).

Baron caught a break when his film was acquired for distribution by Universal International to run as a b-picture at the bottom of double bills, so he got another shot at directing. Pie in the Sky (1964), also known as Terror in the City, starred Lee Grant and Sylvia Miles but flopped. He has two other features in his filmography – Outside In (1972), a film about a draft dodger, and a romance, Foxfire Light (1982), starring Leslie Nielsen and Tippie Hedren – but he spent decades in television, directing episodes of everything from The Love Boat and Charlie's Angels to Room 222 and Kolchak: The Night Stalker.

In Requiem for a Killer, a 2007 documentary about the making of Blast of Silence, Baron reflected sadly that "Hollywood is like a beautiful woman who suffers from an internal disease," and wonders if he shouldn't have stayed in New York and tried to make more small independent films like John Cassavetes, one of his peers. (Erich Kollmar, the cameraman on Baron's film, also shot Cassavetes' Shadows.) When the documentary was made he had retired from the industry had had returned to painting.

(In 2018 Variety ran a story that Baron's assistant had sued him for sexual harassment, after he fired her just four months after she took the job. The lawsuit, which probably got lost in the flurry of far more high profile #MeToo stories at the time, included allegations that Baron bragged about forcing Cuban women to sleep with him to get a part in Cuban Rebel Girls, and about sleeping with Charlie's Angels star Farrah Fawcett. The Variety story ends by noting that the assistant "said she was fired after the two got lost on a trip to a Spectrum cable store to fix his remote.")

Whatever limitations Baron had as an actor, his performance as Frankie in Blast of Silence is perfectly in tune with his laconic film and might have been considered legendary if the character barely opened his mouth, like Alain Delon in Jean-Pierre Melville's Le Samourai (1967). Squint and you might mistake him for a young George C. Scott. (As I did for years whenever I saw stills from the picture, assuming that it was an early role of Scott's.)

And like Le Samourai – or Alphaville, Cape Fear, Point Blank, High and Low or The Long Goodbye – it's a great example of noir turning into neo-noir, quoting a style and a mood just when the world that produced that mood was disappearing. It's a kind of nostalgia for the recent past, and for moral outcomes that doom someone like Frankie from the first frame of a picture.

Today it's hard to imagine wanting to spend just under 90 minutes with a protagonist who hasn't earned the right to redemption. The movie landscape is crowded with readymade anti-heroes who, unlike Frankie, aren't justifiably returned to what the narrator calls "the silence" to the gratitude of both the protagonist and the audience. Because sometimes your anti-hero is simply a villain.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.