The first line in a recent story in Le Monde summed it up: "Japan's political stability is certainly surprising." Lately it's very surprising; I can't think of another country that could appear so outwardly placid despite going through a demographic death spiral, living with a wounded economy for three decades after its bubble burst at the turn of the '90s, and being prone to natural disasters amplified by the country's density and relatively small size. On top of that they have to deal with Godzilla laying waste to their capital every decade.

That's been happening onscreen for seventy years, ever since the radioactive monster waded ashore in Ishirō Honda's Gojira (1954), and it happened again last year when a homage/reboot to Honda's original film, Godzilla Minus One, not just became the most successful Godzilla film ever in Japan but won the first Academy Award in the series' history. It was also the most critically lauded Godzilla picture ever, topping year-end lists and reopening debates on Japan's war guilt by setting the film in the years immediately following their defeat in World War Two.

Not bad for a film that wouldn't exist without a man in a rubber suit crushing toy cities with his floppy feet.

If you're like me you grew up with the countless Gojira sequels made by Toho Studios, usually playing on some endless rainy Saturday afternoon – films with titles like Mothra vs. Godzilla, Destroy All Monsters, Son of Godzilla or Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla. They weren't just bad, they were laughably bad, as Toho turned their monster into a hero, fighting to save Japan from an ever more outlandish series of antagonists. And then, one day someone told you to watch Gojira – not the bowdlerized American version released as Godzilla, King of the Monsters! with interpolated scenes featuring Raymond Burr, but Honda's sombre, tragic original.

Same rubber suit, same floppy feet and toy Tokyo, but you didn't laugh once.

Godzilla Minus One begins with a fighter plane flying low over the water heading for a landing, the camera just behind the bomb hanging from its undercarriage. We're told that it's the last month of the war, and that up ahead is Odo Island – putting us squarely at ground zero in Godzilla lore. In Honda's film this was the first place the creature was seen, after sinking ships all over the western Pacific. In writer/director Takashi Yamazaki's version it's home to an isolated airfield of the Imperial Japanese air force.

The pilot is a hot shot who can bring his fully loaded Zero in on a runway cratered by American bombs; Tachibana (Munetaka Aoki), the chief mechanic, recognizes the young man from his training days, but Shikishima (Ryunosuke Kamiki) was supposed to use that talent to crash his plane into an American ship. He has returned from his mission, claiming mechanical difficulties with his Zero, but Tachibana can't find anything wrong.

When the young man takes offense at Tachibana's implication, he storms off to sit on the shore and sulk, but the mechanic says he understands: "Why obey an order to 'die honourably' when the outcome is already clear?" But that night the garrison is attacked by a massive, dinosaur-like monster, a legend called Godzilla by the island's natives.

Tachibana tells Shikishima to get in his Zero and use its 20mm cannons to destroy the beast, but the young man freezes up and can't pull the trigger. The creature goes on a rampage, killing everyone except the chief mechanic and the young pilot, and we learn later that the military officially blamed the Americans and not the monster.

Sitting on the crowded deck of a ship taking hundreds of defeated Japanese soldiers home, Shikishima is accosted by Tachibana, who hands him an envelope full of photographs – the personal effects of the dead men – and storms away. Back home the young pilot discovers that his parents are dead, killed in the firebombing of Tokyo that left the city a wasteland. His neighbour Sumiko (Sakura Ando) tells him that her own children wouldn't have died if men like Shikishima had done their duty.

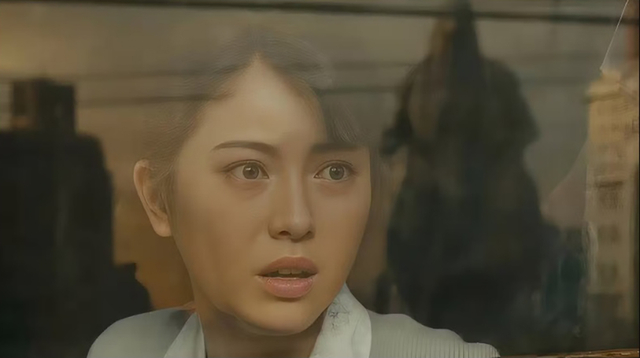

Tormented by guilt and what a modern audience will recognize as PTSD, Shikishima nonetheless tries to rebuild his life, and along the way he ends up sharing his shack chastely with a young woman, Noriko (Minami Hamabe), who is caring for an infant girl given to her by her dying mother in an air raid shelter. With Sumiko's help they tentatively start to bond as an ad hoc family, and Shikishima takes a risky but well-paid job on a boat clearing mines laid by Americans and Japanese all along Japan's coast.

Akitsu (Kuranosuke Sasaki) is the captain, a grizzled veteran sailor, and Mizushima (Yuki Yamada) is a naïve young crewman who regrets never getting his chance to serve. The only other crewman is Noda (Hidetaka Yoshioka), recently a weapons engineer in the Imperial Japanese Navy. The quartet bond over their dangerous duty, relying on Shikishima's skill as a marksman to destroy mines with the ship's heavy machine gun.

It's all going well until 1946 and Operation Crossroads – the U.S. nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll, apparently close enough to Odo Island to dose Godzilla with enough radiation to cause the creature to mutate into a bigger, meaner, more lethal version of itself, and the beast begins a rampage across the ocean, destroying American and Japanese ships.

The "atomic mutation" trope is an old one, going back to before anyone understood the effects of nuclear radiation, and its persisted well past its sell-by date. Ionised radiation inevitably damages and often kills anything it effects, with cell damage introducing cancer into victims' DNA legacy – not producing gargantuan beasts or superpowers. But the appeal of this cherished sci-fi myth is deep and evergreen – a case of metaphor mutating more like imaginary atomic radiation than scientific reality.

With the U.S. military's attention focused entirely on the Soviet Union, the Japanese are told to find a strategy to deal with the marauding beast on their own, which sends Shikishima and his crew out to improvise a weapon using scavenged mines, and to buy time until the Takao, a decommissioned Japanese Navy cruiser saved from scuttling, can arrive on the scene with its heavy guns. But before it can the tiny wooden minesweeper encounters the new, improved Godzilla waiting for them.

The original Godzilla arrived onscreen in a rubber suit out of convenience – the monster was meant to be created using the venerable stop-motion process, but it would have taken years to produce enough footage, so "suitmation" was invented and stuntman Haruo Nakajima was the first man to wear the rubber suit and stomp on Tokyo in Gojira.

The suit evolved to reflect the Godzilla being portrayed by Toho, but even at his most monstrous, there was always something undeniably "derpy" about every suitmation iteration, from his goofy expression caught head-on by the camera to those floppy feet, which never looked like anything but massive house slippers, no matter how many trains they derailed or city blocks they leveled.

The last Godzilla played entirely by a man in a suit was twenty years ago, in Toho's Godzilla: Final Wars. When Hollywood began making their own Godzilla movies, starting with Roland Emmerich's disappointing Godzilla (1998) and then Legendary Pictures' Godzilla reboot in 2014 – the start of a MonsterVerse series that includes pictures like Godzilla vs. Kong (2021) and this year's Godzilla X Kong: The New Empire – they went with a wholly digital monster that's more T. Rex than rubber suit kaiju.

The monster on Odo Island in Godzilla Minus One vaguely resembles his Hollywood cousin, but by the time the mutant Godzilla walks from the sea to begin decimating the Ginza, he has the lumbering walk, beefy legs and tapered neck and head beloved of kaiju purists – a wholly digital Godzilla that nonetheless looks like it could contain a man sweating under two hundred pounds of latex.

Coverage of Godzilla Minus One outside Japan has focused on its tiny budget compared to similar films made in Hollywood. Takashi Yamazaki and Toho made the film for US$15 million with a special effects team of just 35 people; by comparison Godzilla X Kong cost over ten times as much. "It turns out that a well-written script with complex characters you actually care about and a $15 million budget is a whole lot more effective than a $200 million movie with bad writing and generic, one-dimensional characters you forget about the moment you leave the theater," wrote a reviewer in Forbes.

You can call Yamazaki's take on Gojira a re-boot. It certainly respects the original film's lore, and there was something deliberate about setting it not just in the same postwar Japan as Ishirō Honda's original film, but seven years earlier, when the country was still rebuilding from the rubble. (Keeping in mind that when Gojira was made it was set in the present day, in an increasingly prosperous Japan experiencing a miraculous economic recovery just after the end of U.S. occupation.)

Even more interesting is Yamazaki's decision to produce a black and white version, Godzilla Minus Color, that makes side by side comparisons with Honda's film more tempting. There's no comparison, however, between the monsters we see onscreen; Yamazaki's Godzilla is as menacing as it needs to be for a modern audience, and from the moment it emerges from the depths any effort to stop it looks pointless.

After destroying Shikishima's minesweeper's sister ship, it shrugs off a mine they manage to place in its wake and then atomizes the Takao with Godzilla's ultimate weapon – its "heat ray" or "atomic breath". The creature is capable of regenerating itself after absorbing devastating damage, and despite exploding another mine right in the monster's mouth it swims away leaving the little ship dead in the water and both Shikishima and Mizushima injured.

When he wakes up in the hospital Shikishima learns that the government has covered up the destruction of the Takao and hasn't warned its people. "Information control is Japan's specialty," grumbles Akitsu. "This country never changes. Perhaps it can't."

"No one will take responsibility for the chaos," says Noda.

Shikishima returns to the home he shares with Noriko and their baby and decides to move on with his life and make their relationship permanent, but while she's on her way to work on the subway Godzilla arrives in Tokyo Bay, just as expected, and begins laying waste to the Ginza, only just rebuilt after the firebombing, where there's no actual plan to fight the monster's anticipated attack.

Yamazaki, known in Japan for adaptations of anime properties like Doraemon and Dragon Quest as well as live action period films like The Eternal Zero (2013) and The Great War of Archimedes (2019), makes excellent choices to let us feel the size and menace of Godzilla, like the handheld camera shots on the ground, looking up at the looming monster. He also pays tribute to Honda's original film with details like the camera crew and reporter describing the carnage from the roof of a building before Godzilla sends them plummeting to the ground.

The monster ticks another kaiju rampage box by attacking Noriko's train, lifting it into the air in its jaws and forcing her to jump into the Sumida River to save herself. Shikishima finds her wandering dazed in the street just in front of the creature's relentless dismantling of the city when yet another iconic Godzilla trope distracts him – a line of army tanks in front of the Diet building whose barrage of shells only enrage the monster.

Once again Godzilla unleashes his "atomic breath", complete with mushroom cloud and shock waves that surge back and forth through the wrecked city. Noriko manages to shove Shikishima into an alleyway before the blast hits her, and the young man emerges to find the street empty except for bodies and wreckage, no sign of the girl with whom he had intended to rebuild his life. As he screams with rage and grief the "black rain" described by survivors of the Hiroshima bomb begins to fall.

At this point it's worth noting that Godzilla Minus One isn't the only recent Gojira re-boot made by Toho Studios. Shin Godzilla, released eight years ago, didn't have the same impact as Yamazaki's film, though it was a massive hit in Japan. Set in the present day, it told the familiar story of a mysterious monster sighted in the ocean that makes its way to Tokyo where an ineffectual government and military has to rely on outsiders to come up with a weapon to stop the creature.

Directed by Hideaki Anno, renowned for his Evangelion anime series, the film imagined a Godzilla that wasn't just a nuclear mutant but a walking reactor (rendered with a combination of motion capture and digital effects that evoked the "man in a suit"). The film was described as "Lovecraftian", and depicted a creature that went through several stages of mutation as it attacked Japan, one of which – a salamander-like monster that gushes blood from its gills – was rendered as particularly painful and monstrous.

Anno was explicit that, just as the original Gojira was inspired by the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings and subsequent nuclear tests like Crossroads, Shin Godzilla was a response to the recent "triple disaster" – the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami and the Fukushima nuclear plant meltdown. Most of his film is devoted to the slow, confused and ineffectual response of the government and military to the monster; endless new characters are introduced with long descriptions of their official titles onscreen, evolving and growing as the crisis promotes them to new levels of apparent responsibility, attending meeting after meeting in identical offices and conference rooms, pushed to the point of satire.

In an interview with Le Monde after Fukushima, novelist Kenzaburo Oe said that "this disaster highlights the fragility of Japanese democracy. Will we be able to react or will we remain silent? In ten years we will know whether Japan still deserves to be called a democratic nation. I realize that I have never felt so deeply the immaturity of Japanese democracy. Because this crisis is not limited to the Fukushima disaster."

Takashi Yamazaki wrote his script for Godzilla Minus One in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic and told an interviewer that "in those early first few weeks, we had the sense of, 'Hey, the government's not doing anything. This is going to be up to us.' Of course, the Japanese government eventually stepped up later, but I wanted this script to reflect the feeling of people realizing that, presented with a problem like Godzilla, they would have to rise to the occasion themselves to survive."

With the Americans preoccupied by a Soviet threat and the Japanese military afraid to provoke Stalin with a show of force, the Japanese government tells its citizens that they're going to have to come up with a plan to fight Godzilla. The grief-stricken Shikishima commits himself to a scheme devised by Noda – a wholly improbable two-stage attack involving decommissioned navy destroyers sailed by former IJN sailors, huge canisters of freon gas, massive inflatable rafts and explosive undersea compression and decompression. It's about as scientifically viable as the "oxygen destroyer" invented by the original Gojira's reclusive, war-scarred Professor Serizawa, who kills himself along with the monster rather than let his weapon fall into the hands of politicians.

("In short, your plan is full of holes," Akitsu tells Noda after his scheme is put into action. "If you have a better one, let's hear it," replies the scientist. It's actually refreshing to hear a movie acknowledge its proud dismissal of logic or basic physics for once.)

Shikishima is just as suicidal as Serizawa after losing Noriko and signs on to Noda's plan to act as bait for the monster; he agrees to fly a mothballed, experimental Shinden fighter, designed to intercept American bombers during the planned invasion of Japan made unnecessary by the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs.

What he doesn't tell Noda is that he intends to fly his bomb-laden plane into Godzilla's mouth if Noda's plan doesn't work – to fulfill the kamikaze mission he abandoned before Odo Island. He just needs to find Tachibana, the only man apparently capable of getting the Shinden to fly again, enlisting him into his doomed cause by telling the mechanic that "our war is not over."

"We can't rely on the U.S. or Japanese governments," says Hotta (Miou Tanaka), the former IJN officer leading the attack on Godzilla, "so the future of the country is in our hands."

But it's Noda who gets the most stirring motivational speech of the picture:

"This country has treated life far too cheaply. Poorly armored tanks, poor supply chains resulting half of all deaths from starvation and disease, fighter planes built without ejection seats, and finally, kamikazes and suicide attacks. That's why this time, I'd take pride in a citizen-led effort that sacrifices no lives at all! This next battle is not one waged to the death but a battle to live for the future."

This does not go unnoticed inside or outside Japan; an article in Japan Forward, the English-language offshoot of the right-wing Sankei Shimbun, Peter Tasker quotes writer Ian Buruma describing Godzilla as "a very political monster" and speculates that the film signals an "end to pacifism."

"Japan has three nuclear-armed, somewhat hostile countries as near neighbors," writes Tasker. "China, Russia, and North Korea could be considered three Godzillas, a large one, a medium-sized one, and a small but vicious one. Russia's invasion of Ukraine came as a particular shock to Japan. It put paid to delusions about the UN and indicated that might is still right in the international arena. Unsurprisingly, there has been almost no pushback against the government's plan to double defense spending. Japan's armament manufacturers are already forecasting bumper profits. This is the context in which the latest Godzilla movie has been made."

And in a National Review article, Michael Washburn wrote that "If a movie came out presenting recently demobilized Wehrmacht soldiers as heroes – and conveying the message that these Nazis may have taken a licking but still had some fight in them – audiences and critics around the world would rightly revile the film as the morally repulsive garbage it would be... Something's wrong here."

In the Le Monde article quoted at the start of this column it's noted that a slush fund scandal is just the latest one threatening the Liberal Democratic Party, Japan's longstanding ruling party, and that Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has an 80 per cent disapproval rating. Half of Japan's voters no longer go to the polls during elections.

Given the apparently longstanding suspicion of the motives and competence of its government, as expressed even in monster movies, it's hard not to speculate that there's a kind of death wish hiding behind the placid, prosperous, orderly and homogenous surface of Japanese society. And that it could be the reason Japan endlessly imagines some monster, part horror and part hero, wading ashore regularly to expose the systemic incompetence and force a reset under the weight of its floppy, rubbery feet, always about to return.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.