It was self-evident that things were going very wrong in the '70s – if you couldn't miss it as a kid, it must have been obvious for adults. The centre – if there was one anymore – was not holding, and the evening news was a catalogue of all the parts that were falling away, a litany of hijackings and kidnappings, serial killers and political scandals, while great cities subsided into bankruptcy and what were once called perversions graduated from moral failings to mere vices on their way to marketable lifestyle choices.

In his famous New York magazine article where he coined the "Me Decade", Tom Wolfe took the focus from the news to ourselves. Inspired, he observed, by the tagline of a 1961 Clairol ad campaign ("If I've only one life, let me live it as a blonde!") the adults had embraced a radical narcissism:

"One's very existence as a woman – as Me – becomes something all the world analyzes, agonizes over, draws cosmic conclusions from, or, in any event, takes seriously. Every woman becomes Emma Bovary, Cousin Bette, or Nora ... or Erica Jong or Consuelo Saah Baehr...Among men the formula becomes: 'If I've only one life, let me live it as a ... Casanova or a Henry VIII.'"

Men felt not just resigned but encouraged to leave their wives, Wolfe wrote: "The right to shuck overripe wives and take on fresh ones was once seen as the prerogative of kings only, and even then it was scandalous." But now marriages and families – indeed whole identities – were being torched by unremarkable men and women striving to find their better selves with a religious fervor; if hashtags existed they'd be justifying it as FOMO (fear of missing out) because YOLO (you only live once). In the middle of all this Hollywood dropped films like Dog Day Afternoon.

"What you are about to see is true..." read the title on a black screen, before Sidney Lumet's film went into a montage of gritty, grimy New York City basting in the late summer sun while Elton John sang "Amoreena" from his 1970 record Tumbleweed Connection: "Just lately, I've been thinking, how much I miss my lady."

On August 22, 1972 two men, John Wojtowicz and Salvatore Naturile, tried to rob a bank in Brooklyn and began a standoff with police and the FBI that lasted fourteen hours while they held bank staff as hostages. Exactly a month later Life magazine published a story about the botched holdup, "The Boys in the Bank," written by Thomas Moore and P.F. Kluge, in which it was observed that Wojtowicz bore a resemblance to actors Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino, the latter of whom had become a major star with the release of The Godfather six months previous.

The story was brought to agent Martin Bregman, who had just moved into production with Serpico, a film built around his client, Pacino. Bregman hired Frank Pierson to write a screenplay and with backing from Warner Bros. brought it to Serpico director Lumet. Pacino was signed to play Wojtowicz (whose name was changed to Sonny Wortzik when Wojtowicz, then serving time in a federal penitentiary, wanted more money for the rights to use his name).

But shortly after pre-production started Pacino backed out, saying he was exhausted after making The Godfather 2 and wanted a break, knowing first-hand how demanding Lumet could be as a director. For a brief moment Dustin Hoffman was in talks to take over the role of Sonny. But Pacino was persuaded to return, and we lost the tantalizing prospect of Dog Day Afternoon starring Hoffman – potentially a very different picture.

When Lumet's opening montage ends and Elton John's song fades from the soundtrack to the speaker on a car radio, the camera settles on Pacino's Sonny and his accomplices, Sal (John Cazale) and Stevie (Gary Springer). As the bank security guard takes the flag down before locking the front door, they make their way separately into the bank; Sal quietly takes out a submachine gun while meeting with Mulvaney the bank manager (Sully Boyar), whispering for him to remain quiet; a moment later Sonny pulls a rifle out of a flower box and announces that the robbery has begun.

We know it's begun badly when the rifle barrel gets snagged on the ribbon around the flower box and Sonny flails for a moment trying to shake it loose. Shortly after Stevie backs out, handing Sonny his gun; Pacino angrily tells him not to take the getaway car. "How am I gonna get home?" Stevie asks.

"Take the subway."

The first half of the film is full of moments like this, and it's hard to tell if it's a comedy or a true crime flick; screenwriter Pierson recalled later that someone told him that it was a "tragic comedy."

Sonny thinks he had all the angles covered until he discovers that the bank's safe is nearly empty; the Brinks truck had done its pickup earlier that day. He tries to burn the deposit ledger but that only sends smoke out the vents and into the street; disappointed, he and Sal are about to cut their losses and leave when the phone rings and the manager says the call is for him.

Between the smoke and the distractions Sonny hadn't noticed the police that have set up in the barbershop across the street, where Sgt. Moretti (Charles Durning) can look right into the bank while he talks with Sonny on the phone. The robbery is over and the hostage situation has begun and busloads of police arrive to surround the bank, cordoning off the street to hold back the crowd and the media descending on the scene.

Sonny is forced to improvise, and among his first decisions is to cast Sal as the wild card, likely to start shooting hostages while Sonny is the reasonable one, ready to negotiate with the increasingly frantic Moretti who seems barely able to hold back his own men, as they edge toward the bank door with their guns drawn. The rapid response of the police has turned the botched holdup into a siege – his first mistake, Moretti admits to FBI agent Sheldon (James Broderick, father of Matthew "Ferris Bueller" Broderick), who arrives intent on taking over the crime scene.

"I'm a Roman Catholic," Sonny tells Moretti, "and I don't want to hurt anyone."

To recreate the scene around the real-life Chase Manhattan Bank branch in Gravesend, near Coney Island, Lumet had found a two-storey warehouse in Park Slope, between Prospect Park and Greenwood Cemetery. They built the bank set on the main floor and put their production offices upstairs so that they could shoot continuous takes following Pacino from inside the bank to the street outside.

The cast ended up being built around Pacino, with friends from theatre like Durning and Penelope Allen as Sylvia, the head teller; Pacino had lived with Allen and her husband when he was a struggling theatre actor. Lumet took a leap of faith casting John Cazale, who in no way resembled his real-life character, but Pacino and Cazale – also an unknown until his performance as Fredo in the Godfather films – were close friends and their relationship was crucial in building their performances.

Lumet was part of a generation of directors (Norman Jewison, John Frankenheimer, Arthur Penn, Robert Altman, William Friedkin) who got their start in television; his first film, 12 Angry Men (1957), was based on a live teleplay that aired on CBS. Like many of his peers he wasn't distinguished for any obvious, auteur-derived style as much as letting the stories dictate how his movies looked.

"Discussions of style as something totally detached from the content of the movie drive me mad," he wrote in his 1995 book Making Movies. "Form does follow function – in movies too... Critics talk about style as something apart from the movie because they need the style to be obvious. The reason they need it to be obvious is that they don't really see."

So while everybody agreed that Pierson had delivered a fantastic script (he'd win an Oscar for it – the only one the picture got in a year when it had to compete with One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest) he allowed his cast to improvise dialogue to help their characters distinguish themselves during the long scenes they're stuck inside the bank.

The half dozen actresses playing the women held hostage by Sonny and Sal do a great job distinguishing themselves as they cope with the fear and the heat; a few of them can't hide their excitement as the focus of attention from the crowd and the news media outside. As the standoff continues several of the women show signs of what would later be called Stockholm Syndrome. Lumet asked them to provide their own wardrobe for their characters, paying them an extra two dollars a day if they did.

(Keep your eye out for Carol Kane as Jenny, a proto-goth in a black vintage-styled dress with her hair braided and pulled into tight buns on either side of her head, very much in keeping with the actress' own persona as it would emerge in the next few years in Taxi and Annie Hall. Anyone old enough to remember a time before ATMs and online banking will remember spending hours every month in a bank, depositing paycheques and paying bills and withdrawing money. It would have made establishing mood with the audience infinitely easier, as nearly everyone would have experienced time spent in some bank branch as a hostage experience.)

Ultimately it's Pacino's Sonny who really thrives with the attention he gets from the NYPD and the FBI and especially the crowd hugging the barricades, who cheer him with a roar when he emerges through the bank's front door to bargain with Moretti and taunt the rows of cops and detectives who are poised to pounce, like hunting dogs who've cornered their quarry.

The high point of his relationship with the crowd is when he rants that Moretti and his men can't wait to kill him, which prompts him (in what was also an improvised moment) to bellow "ATTICA!" over and over, sending the crowd into a frenzy by invoking the 1971 prison riot in upstate New York that left 33 inmates and 10 guards dead – an eruption of chaos and unrest that set the tone for the ensuing decade.

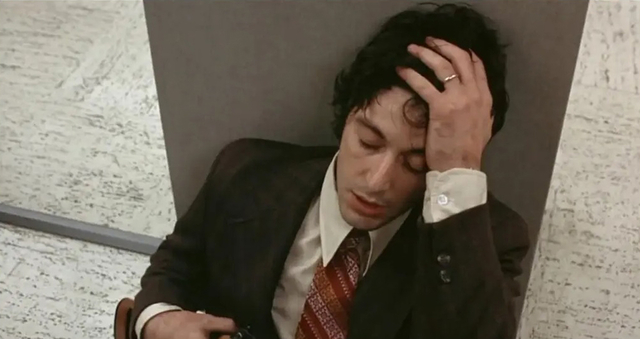

It was, as Lumet wrote in Making Movies, Pacino's Sonny "feeling his power for the first time after a lifetime of failure."

"Sidney Lumet helped me with that," Pacino recalled in a collection of interviews with New York Times writer Lawrence Grobel published in 2006. "He said 'It's his day in the sun, with all those people out there.' Charging at windmills, somebody once said to me."

Pacino also noted another scene that he considered key to the film, where a boy with a period-perfect afro delivers pizzas to Sonny and the hostages, then turns to the crowd and, barely able to contain himself, leaps into the air and screams "I'm a fuckin' STAR!"

"It hit right where we're at," the actor noted, "the kind of energy wrapped up in the media and with imagery and fantasy and film. We don't know enough about media yet, we don't know its effect on us. It's new. It's got to do something to us."

Years later, talking to Grobel, he remembered that moment again. "Dog Day was at the early stages of television entertaining itself. It was the early stage of the car chase. It was the first time when the pizza boy delivers the pizza and turns around and says 'I'm a star!' That was the first time that kind of recognition vis a vis TV and the real world was shown. In a way it was reality TV."

I don't have any memory of John Wojtowicz and the 1972 hostage taking, but I have very clear memories of Lumet's movie – in my own mind as nearly indistinguishable from the original incident as if it were a documentary – and the posters and TV ad campaigns that seemed to push the movie non-stop when it was released in the fall of 1975.

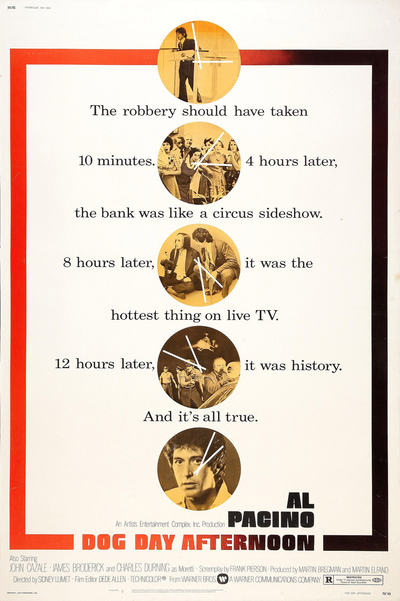

There was one poster in particular and its very effective copy: "The robbery should have taken 10 minutes. 4 hours later, the bank was like a circus sideshow. 8 hours later, it was the hottest thing on live TV. 12 hours later, it was history. And it's all true."

The film and its media messaging gave a warning to the 11-year-old me – this was the world you were living in, full of scandal and random violence and mayhem that will be covered in real time to the best of the ability of what seemed like all-powerful television networks funded more lavishly than most governments. I didn't remember the Brooklyn bank hostages, but I certainly remembered the Watergate coverage that pre-empted hours of daytime television programming, and the Munich Olympics, which had turned into a tragedy right on TV.

And don't forget that Lumet's next picture would be Network. (About which my dear friend Kathy Shaidle wrote in this space that Lumet had "never been less 'eat your liberal spinach' than here, to the point where I wonder if he really directed Network at all.")

But Pacino's Sonny starts to lose the crowd as the sun goes down, when he asks Moretti to have his "wife" brought to the hostage scene from a mental hospital.

John Wojtowicz had been married – illegally, as the priest who performed the service was later defrocked – to Ernest Aron, later known as Elizabeth Eden. The bride wore white and the bridesmaids were all men, and the Vietnam veteran groom wore his army dress uniform and medals. Wojtowicz, who already had a wife and two children, was a bisexual described by people who knew him in the Greenwich Village gay scene as sexually obsessive, and the news reported that his motivation for the bank robbery was getting Aron (renamed Leon for Lumet's picture) money for sex change surgery.

In Making Movies Lumet wrote that "by the third day of rehearsal, I had become nervous about an area that had nothing to do with the quality of the script or the actors. Here was a story that, in plot, was about a man robbing a bank so his boyfriend could have the money for a sex-change operation. Pretty exotic stuff for 1975. Even The Boys in the Band had gotten nowhere near that aspect of gay life."

Lumet knew that handling this subject matter was crucial to how his film would land in theatres. He started with casting Chris Sarandon as Leon, who committed himself fully to the part, plucking his eyebrows and teasing his hair and practicing walking around his apartment as if he were in heels. But in rehearsals Lumet asked him to dial back his presentation of Leon, suggesting "a little less Blanche DuBois and a little more Queens housewife."

Lumet was concerned most of all how the picture would play at the Loew's on Pitkin Avenue in Brooklyn, the neighbourhood movie house of his childhood. "It wasn't the most sophisticated crowd that piled in on Saturday night. I remember rude remarks being yelled down from the balcony at Leslie Howard in The Scarlet Pimpernel."

We watch as the crowd palpably begins to heckle Sonny once his relationship with Leon breaks on the news, and Lumet had to be careful that crowds in the theatres didn't do the same thing. "This was going to be played to the same kind of audience that filled Loew's Pitkin on Saturday night," he wrote. "God knows what might come down from that balcony

A few years later while shooting Cruising with director William Friedkin, when the film's New York locations were being picketed by gay activists protesting the film's depiction of their community, Pacino told Grobel that he had expected this reaction when shooting Dog Day Afternoon.

"Nothing else even comes close. I don't like this trouble. I have never stayed in any political arenas. It's just not my thing. The sociopolitical aspects of the films I make are never the front-runner in my mind. It's always the story, the character. This picture is getting international attention, the media are coming up with stories, and it's not me they're talking about. They're talking about the issue. It's such a volatile subject. Still, there is something wrong. This film could be made without me."

What Pacino did make Dog Day Afternoon without was any input from John Wojtowicz, the real-life model for Sonny. Wojtowicz had denied Frank Pierson's repeated requests to meet him when he was writing the screenplay, holding out for more money for his story. In the end Pierson had to knit together Sonny from interviews he'd done with the hostages and friends and family of Wojtowicz, deciding that his character's tragedy was an eagerness to please – to make everyone around him happy, from Sal to Leon to the hostages to the crowd.

Since Lumet's film became a classic there have been many articles and two documentaries about Wojtowicz, who actively sought the celebrity. The Dog came out in 2013, six years after Wojtowicz died, but Dutch director Walter Stokman made Based on a True Story in 2004, and the picture they paint of Wojtowicz is a raging sociopath – a narcissist and the wholly unreliable narrator of his own story who demands control over Stokman's picture that he was unable to achieve the day he robbed that bank.

(Wojtowicz claims that after getting out of prison he applied to Chase Manhattan for a job as a security guard, and it might actually have happened. What's true – and even stranger = is that one of the hostages later recorded and released a 45rpm single called "Lollypops & Shotguns" telling her side of the bank robbery in song.)

One of Pierson and Lumet's departures from the real story was a scene where FBI agent Sheldon tells Sonny that he's impressed with how well he handled the whole situation, and hints that if he keeps cool they'll take care of Sal, who they consider the threat. Wojtowicz claimed later that when the movie was screened at his prison he became a marked man for betraying his friend, and was the victim of a gang rape by eight black inmates. As with anything Wojtowicz said, it may or may not be true.

Both Pacino's Sonny and the real Wojtowicz were challenges to gay stereotypes, but one cliché that does appear in Lumet's film is the overbearing mother, played by legendary actor Judith Malina in one of several standout scenes. The gallery of great performances in the picture obscures the achievement of Lumet, whose pacing and blocking are impeccable and do so much to showcase everyone in front of his camera.

In the end Pacino admitted that he "avoided meeting the guy in Dog Day Afternoon because I had an idea of the kind of person I wanted to play. That was a mistake - it would have served me to meet him. It always does."

And despite a long career full of great roles (Bobby in Panic in Needle Park; Michael in The Godfather; Vincent in Heat; Ricky in Glengarry Glen Ross; maybe Tony Montana in Scarface) his Sonny will remain among his best, and he knows it. Joking with Lawrence Grobel as they looked back over his career, Pacino remembered how "somebody at a press conference once asked me, 'Do you think you'll ever be as good as you were in Dog Day?'"

"And I said, flatly, 'No.' That answered that."

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.