Alfred Hitchcock's classic period begins, roughly, from the moment he signed a production deal with Lew Wasserman and Paramount Pictures in 1954. Hollywood loves to praise directors for thriftiness, for coming in on time and on budget and making a virtue of "less is more." But this rule doesn't apply to everyone, even less to a genius. Freed from the strict economies of his budgets with Selznick and Warner Bros., Hitchcock was ready to demonstrate that, when circumstances dictate, more is more.

What there wasn't more of when the director started work on Rear Window was Hitchcock himself. In his biography of the director Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light, Patrick McGilligan notes that he had dieted himself down to 189 lbs. from 340 lbs. – the slimmest he would ever be. He responded by making a film that didn't budge from a single location, shot on a single soundstage on the Paramount lot.

The prize for best Hitchcock film is subjective. For many people it will always be Psycho, for others it's Vertigo, his most intense and self-referential picture. You can make a convincing case for North by Northwest on its dynamism alone. In most cases the pictures picked will be from this classic period, starting with Rear Window and ending with either Psycho in 1960 or The Birds in 1963. For me it's Rear Window, mostly because of a protagonist who I identify with more than any other in the director's long career.

The film begins with that protagonist, snoozing in a wheelchair, his leg in a cast. After establishing that it's a hot summer day with a shot of a thermometer, the camera pans down his leg to read a joking message written on the cast, letting us know that we're looking at L.B. Jeffries (Jimmy Stewart). The pan continues into the room, picking out details like a smashed camera on a table and, behind it, a framed photo on the wall of an accident on a racetrack, one of the cars frozen mid-air as it hurtles toward the photographer.

Jeff, we quickly learn, is that photographer. On his walls are more framed photos – some street photography, a photo of a nuclear bomb test, a trio of war pictures, one of which shows two men in flight suits in front of a twin-engine plane. We see a big film negative in a lightbox showing a woman's face, and that face on the cover of a magazine that, though the name is obscured, is very clearly LIFE. (Henry Luce, publisher of LIFE and Time, apparently didn't give Hitchcock permission to use the magazine's name.)

Since we'll spend the rest of the picture in this room with Jeff, we pick out more details – his hodgepodge of furniture, including a brass-bound wooden chest of drawers picked up, we presume, on his travels, on top of which sits what looks like a Turkish coffee set. Bookshelves are packed with leaning volumes – technical reference books, bound photography annuals and ledgers and records; in the age before computers the freelance creative business required extensive records and bookkeeping come tax time. And there are cameras – all kinds of cameras and lenses and flashes and accessories, in bags and on shelves, and countless little boxes in telltale Kodak yellow. I recognize the room because I've lived in different versions of it for four decades now.

It's the kind of place a busy photojournalist would live – just two rooms, big enough to keep what doesn't fit into a suitcase and a camera bag; a bolthole that was never meant to be inhabited continuously for seven weeks. Jeff is hot and bored and irritated, and his only outlet is outside his apartment's sole feature – a picture window that looks across a courtyard at all the other apartments on the inside of this Greenwich Village block.

To paraphrase Proverbs, an idle mind is the devil's workshop, and six weeks of solitary confinement with a view have turned Jeff's talents to a voyeur's trade. Hitchcock's films would get more lavish with his new Paramount contract, but for Rear Window he tasked the studio's crew with making Jeff's view as realistic as possible. They ended up cutting out the studio floor to create the gardens and walls of the courtyard and built right to the studio ceiling – thirty-one apartments in total, though only a dozen were fully furnished.

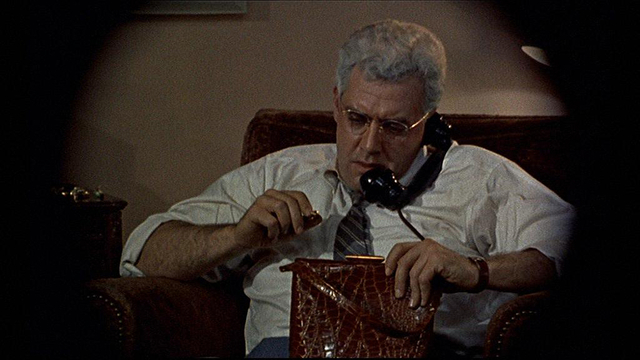

And in those apartments are people. In the absence of names there are only types: a couple with a small child, an older couple with a pet bird in a cage, a middle-aged sculptress working on Henry Moore-esque abstracts. She's just one of the bohemian contingent you'd expect in the Village; there's the composer (Ross Bagdasarian, later better known as David Seville, creator of Alvin and the Chipmunks) with his piano on display behind an artist's skylight, and the curvy blonde ballet dancer (Georgine Darcy), often barely clothed behind her own picture window, dubbed "Miss Torso" by Jeff.

There's the bickering couple with the invalid wife, and a middle-aged couple and their little dog, who they let down to run in the courtyard in a basket on a rope from the fire escape where they sleep on airless New York summer nights. There's "Miss Lonelyhearts" (Judith Evelyn), the spinster drinking her way through solitary evenings, and the newlywed couple who spend most of the film behind drawn blinds, the husband emerging briefly for a smoke in his undershirt and pajama bottoms before being called back in by his apparently rapacious bride.

As ever, Hitchcock's shooting script was full of notes red flagged by Joseph Breen and the Production Code, and the director was happy to push back at his old adversary. There was Miss Torso, of course, and the newlyweds before you ever got to the grisly details of the murder at the (theoretical) centre of the story. But unlike Warners, Paramount was a willing partner in his skirmishes with the censors.

He invited officials from the Motion Picture Production Code to view his impressive set, explaining that nearly everything they objected to would be seen from too far away to be a problem for audiences. As usual he made minor concessions but made them seem like major compromises. In any case, as McGilligan writes in his biography of the director, "Joseph Breen was nearing retirement by the time Rear Window went before the cameras. No one followed through on many of his objections to the script. And Breen was replaced by the Englishman Geoffrey M. Shurlock, who was more open and liberal in his attitude, more open (and resigned) to the idea that screen values were moving with the times."

But even more important is who's in that room with Jeff. There's Stella (Thelma Ritter), the salty nurse hired by the insurance company to look after him while he's immobile, and his old war buddy Tom Doyle (Wendell Corey), an NYPD detective who was the pilot of the reconnaissance plane where Jeff operated the camera. And there's Jeff's girlfriend Lisa (Grace Kelly), who appears to him through the haze of a heat-induced slumber with a close-up that's one of the most famous shots in Hitchcock's career.

She is, no one can deny, a vision of loveliness, and the pinnacle of the director's infamous obsession with cool blondes – a critical talking point that has (I think) been overplayed since Donald Spoto made it the centerpiece of The Dark Side of Genius, his bestselling 1983 biography of Hitchcock. She's a creature of Park Avenue who floats into Jeff's dismal little West 10th St. crash pad wearing an $1100 dollar dress right off the plane from Paris. (That's nearly $13,000 dollars in today money.)

We're meant to understand that she is, or was, a model, but is involved with the daily running of some fashion retailer that goes beyond the duties of a mannequin. She's friends with Leland Hayward and Slim Keith (as was Hitchcock) and she plants mentions of Jeff in newspaper columns while arranging to have a catered lobster dinner from "21" delivered to his apartment.

She's perfect – "too perfect" according to Jeff – and the big conflict in their relationship is that they're far too different as people to have a future together. He resists her suggestion that he cut back on the travel and set himself up in New York shooting fashion and portraits, and he finds it impossible to imagine that she'd survive the war zones, famines and disasters where he finds his subjects.

(Jeff has the bohemian's knee-jerk disdain for postwar middle-class affluence; he complains about "rushing home to a hot apartment to listen to the automatic laundry and the electric dishwasher, the garbage disposal and the nagging wife." It's still hard to understand the horror mere appliances elicited in self-styled rebels back when they were new.)

It's frequently stated that Jeff was based on pioneering photojournalist Robert Capa, who had an affair with actress Ingrid Bergman that inspired the script John Michael Hayes wrote with Hitchcock (based on a pulp short story written by Cornell Woolrich). In any case the presumed conflict between Stewart's restless masculine quest for creativity and adventure and Kelly's attractive invitation to a well-heeled uptown version of domesticity (I can't imagine a bungalow in Levittown is in her plans) has provided fodder for endless critical dissections of gender dynamics in the film.

For much of Hitchcock's golden period at Paramount, he switched between Stewart and his standby protagonist, Cary Grant, for his heroes. (With a detour to Henry Fonda in The Wrong Man.) It's hard to imagine Grant in that cast, confined to that wheelchair, and Hitchcock had Stewart (and Kelly) in mind for the film from the moment he started planning it with Hayes.

Stewart was a contrast to the fussy and difficult Grant, and in his biography of the director, McGilligan writes that he "punched into work like a guy carrying a tin lunch box. Stewart was more of a partner, and the Hitchcock-Stewart films were organized as partnerships, with Stewart's company sharing a percentage of the gross and profits – and risk. As with Rope, Stewart paid himself a reduced salary, taking the chance of making more money on the back end. The director knew from experience that such an arrangement wouldn't work with Cary Grant, but after Rope, Stewart would be involved this way in each of his other three films with Hitchcock, from the script stage through to the end of production."

I've never known a photographer who reminded me of Cary Grant. (I don't think anyone's ever known anybody like Cary Grant.) But I've met plenty of photographers who reminded me of Stewart's Jeff – a bit of an overgrown boy animated by nervous energy, fond of one-upping you with a hairy story, full of arcane technical knowledge and adamantly held opinions that fall apart when applied to the many situations outside their vividly-experienced but experientially narrow lives.

So I'm right with him, in that wheelchair, when he switches from his field binoculars (doubtless acquired from army surplus, but chosen carefully) to the 35mm camera with the big telephoto lens while snooping on the suspicious events in the apartment of the brooding husband (Raymond Burr) and his bed-ridden but difficult wife (Irene Winston).

McGilligan, like many other viewers, confidently states that Stewart is using a Leica to spy on his neighbours. It's been called the most iconic camera in movie history, and I'll give you that if only because there's not a lot of competition. But you won't be surprised that it's been the subject of some serious geekery among camera buffs intent on nailing down the make and model of Jeff's camera.

But I'll cut to the chase and tell you that the camera is an Exakta VX made by Ihagee in Dresden, East Germany, the export version with the pentaprism viewfinder, mounted with a Kilfitt 400mm f5.6 telephoto lens, made in Munich, West Germany. It was a serious piece of kit that cost Jeff several thousand dollars – a lot of money for, as he tells Lisa during one of their arguments, "a camera bum who never has more than a week's salary in the bank."

The Exakta logo has been covered up with black tape or leatherette by someone in Paramount's prop department – there's speculation that it was because the camera was from behind the Iron Curtain but that doesn't make any sense to me; what I do know is that I've met photographers who tape over the logos on their cameras, some claiming that they don't want to provide advertising for companies that don't support them professionally.

I've never really bought this, but what's certain is that whoever chose the camera for Stewart to hold in Rear Window knew their stuff; it would be at least another decade before Nikons and Canons became the tool of choice for photojournalists, and there was no industry standard for 35mm single lens reflex cameras that mounted really long telephoto lenses in 1954. The Exakta was a great choice; what I don't understand is why Jeff wasn't using it instead of the smashed Graflex press camera on his table to get that shot at the racetrack. He would have been standing right on the track to take that photo; it's a miracle he got away with a broken leg.

(On the phone with his editor Jeff complains that "you wanted something dramatically different," but I suspect it had something to do with an art director who insisted that large format press cameras were the only serious professional choice and that 35mm cameras like the Exakta were just toys. There were still idiots like this in charge of art departments as late as the '70s.)

So when Jeff raises that Exakta with the big telephoto to his eye he's moving from casual peeping tom to professional voyeur, and initiating the debate about voyeurism that's meant to trouble Jeff, Lisa, Stella and Tom as they stand in Jeff's room looking out that big window. "We've become a race of peeping toms," Stella sourly notes early in the film, and when talking about his obsessive surveillance of his neighbours and of the invalid's husband after his wife goes missing, Lisa pleads wearily that she's no expert in "rear window ethics."

Hitchcock was a director too concerned with detail and control to allow anything accidental into his pictures. Which is why the emotional crescendo in Rear Window isn't during the suspenseful cornering of Burr's murderer at the end of the film but earlier, when the little dog belonging to his upstairs neighbours (The Dog Who Knew Too Much, as Hitchcock joked) is found dead, its neck broken, in the courtyard one night.

Grief-stricken and distraught, the wife screams accusations at her neighbours while Miss Lonelyhearts gently places the dog's body in the basket for the husband to pull back up to their balcony. "Which one of you did it?" she pleads, as unlikely to know her neighbours' names as Jeff. "Neighbours like each other, speak to each other, care if each other lives or dies" she wails, adding that her dog was "the only thing in this whole neighbourhood who liked anybody."

It's a raw, disconsolate vignette, rare in a Hitchcock film, and it anticipates stories like the murder of Kitty Genovese in Queens by a decade. My friend Kathy Shaidle once wrote how the gruesome rape and murder of Genovese, reputedly while several dozen of her neighbours watched and listened for a half hour, was a case of misreporting turned into urban myth, in the service of a growing belief that cities make us anonymous and estranged, even helping coin a term in social science: the "bystander effect."

The scene shows just how in tune Hitchcock was with his audiences and their many anxieties, the better to manipulate them in the service of his stories of suspense and everyday evil. We certainly aren't asked to feel nearly as much grief for the invalid wife who was, from what Jeff sees from his window and what Stella surmises, probably dismembered in the bathtub and distributed piecemeal up and down the Hudson and the East River.

Burr's murderer killed the dog just as surely as he killed his wife, but Hitchcock pointedly makes us mourn the little dog more than the bedridden but peevish woman who we glimpse mocking her put-upon husband and tossing away the rose he cut from his garden and placed on her breakfast tray.

When the film ends the camera pans over the scene from Jeff's window for a final glimpse of his neighbours. Miss Torso welcomes home her beau – a sawed-off little GI named Stanley; Miss Lonelyhearts and the Composer are in his studio listening to a recording of the romantic ballad he's been struggling with throughout the picture. ("Lisa," written by Franz Waxman for the film, which would be his last for Hitchcock.) The middle-aged couple are putting their new dog in the basket to lower down to the courtyard. Painters are at work in the murderer's empty apartment and the newlyweds have started bickering.

Stewart is back in his wheelchair, both legs in casts thanks to his fight with Burr's murderer during the climax. (In his famous 1962 interviews with Hitchcock, French director Francois Truffaut asks if Rear Window could be "interpreted as a picture of impotency." "It could be, yes," Hitchcock responded. "The impotency of plaster.") Kelly – now wearing dungarees and penny loafers, sees that Jeff is asleep and puts down the travel book she's reading and picks up a copy of Harper's Bazaar. You can't help but hope that another seven weeks in the wheelchair will help Jeff realize that he's being an idiot.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.