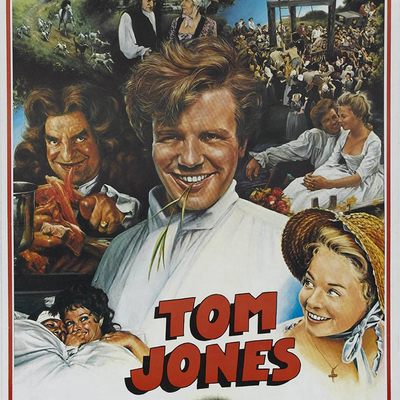

When it looked like Tom Jones was going to dominate the 1963 Oscars, there was a concerted effort by Hollywood to prevent a British film from sweeping the awards. Never mind that the only truly British film to win for best picture had been Laurence Olivier's Hamlet in 1948; David Lean had won for Lawrence of Arabia the previous year, and with The Bridge on the River Kwai in 1957. Lean's producer, Sam Spiegel, was American, and had the backing of distributor Columbia Pictures behind him.

Lean was also a verifiable genius, but this looked too much like a British invasion on movie screens to match the one quietly bubbling under on the pop music charts, so a campaign was waged behind Lilies of the Field, a pious and right-thinking film though a dull one compared to Tom Jones. Lilies star Sidney Poitier ended up winning for best actor, but Tom Jones won for best picture, director, adapted screenplay and musical score. It was also the fourth biggest film at the box office that year, ahead of The Great Escape, Bye, Bye Birdie, Charade and Irma La Douce, but behind It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, How the West Was Won and Cleopatra.

(The last of which proves that you can nearly bankrupt your studio but still pack theatres with crowds who want to see a trainwreck.)

Lilies of the Valley appealed to the conscience, but Tom Jones – a period picture set in 18th century England, based on a book students complain about when it's on reading lists – captured the zeitgeist. You can make noises about incipient Beatlemania, but the Beatles wouldn't play their first U.S. concert until eight months after Tom Jones hit theatres, and "Swinging London" wouldn't enter the lexicon until Time magazine wrote about it in the spring of 1966.

What did Tom Jones know, and why did movie audiences respond to it when George Wallace blocked the doors of the University of Alabama and Lesley Gore's "It's My Party" topped the Billboard charts?

Confounding expectations, director Tony Richardson chose to begin his version of Henry Fielding's 1749 novel like a silent film, complete with title cards for dialogue and a tinkling harpsichord on John Addison's soundtrack. Squire Allworthy (George Devine) returns to his country estate to find a baby in his bed; household suspicion falls upon a maid, Jenny Jones, with the barber Partridge (Jack MacGowran) accused of fathering the child. The errant servants are banished and Allworthy proclaims that the foundling will be raised by his spinster sister Bridget (Rachel Kempson) as if the boy was his own son.

As Walter Lassally's hyperactive, handheld camera finally comes to rest on the sweet-faced baby lying in Allworthy's bed, the narrator (Micheál MacLiammóir) informs us that he will be known as Tom Jones and that he was "born to be hanged."

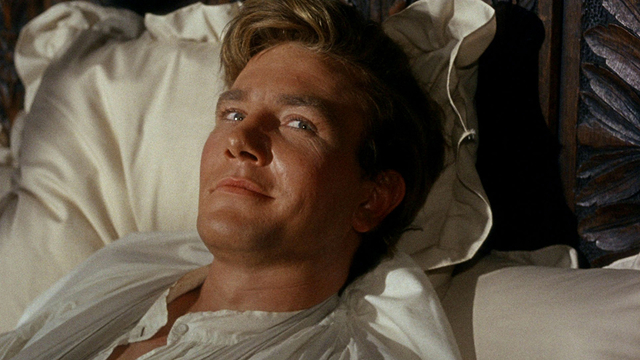

The baby grows up to be a strapping, handsome lad played by Albert Finney. For many people who only know Finney from roles in films like Murder on the Orient Express, Annie, The Dresser, Miller's Crossing or Erin Brockovich, confronting a very young Finney (twenty-six when he made the film) is a shock. Tom is a lusty lad and Finney inhabits him fully, with a thick head of hair and charisma that sells him as blessed and cursed with the favour of every kind of woman from country trollop to London lady.

Postwar Britain was, for one of those rare spells in its history, a place of real social mobility and Finney, the son of a Salford bookmaker, had gone from the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art to a series of stage roles that caught the attention of Tony Richardson, who cast him alongside Alan Bates as Laurence Olivier's sons in The Entertainer (1960). Richardson was one of the "angry young men" behind "kitchen sink" realism in British theatre and film, and when his Woodfall Productions made a film out of Alan Sillitoe's novel Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960, directed by Karel Reisz), Finney had the starring role in only his second picture.

Reisz and Sillitoe's story of a machinist in a Nottingham bike factory carrying on an affair with a friend's wife while pursuing another woman is cramped and low-ceilinged compared to Tom Jones. Shackled to the kitchen sink, it's preoccupied with the narrow domestic choices left to young working-class men in the absence of larger ones in their life or career. The movement from one role to the next for Finney says a lot about the pace of social change brewing in England as a new decade was starting.

Despite marginal status as a bastard, Tom is much favoured by Squire Allworthy despite competition from Blifil (David Warner), his sister's son from a subsequent marriage. He's just as popular with their neighbour Squire Western (Hugh Griffith), whose lovely daughter Sophie (Susannah York) has the whole of his romantic yearning even if his physical attentions are dispersed among the girls of the parish, like Molly (Diane Cilento), the daughter of local "gamekeeper" (read: poacher) Black George (Wilfrid Lawson), Tom's frequent hunting companion.

Allworthy might be the moral fulcrum of their rural community but Western sets the tone, and Griffith gives a hilarious performance as a man who has lived without any apparent restraint on either appetite or impulse. On his own he makes Richardson's picture period correct; unkempt and florid-faced, bulbous-nosed and pop-eyed, he looks like he's stepped right out of an engraving by William Hogarth, one of Fielding's closest friends and colleagues.

Fielding was in at the start of what anyone who's ever taken an undergraduate course in the history of modern fiction will know as the sentimental novel, a genre that began in England in 1740 with Samuel Richardson's Pamela. This was so wildly successful that Fielding was moved to write an equally popular satire, Shamela, which gave him a taste for the creative (and fiscal) potential of the novel.

He wrote Joseph Andrews, telling the story of Pamela's brother without as much derisive humour, shifting tone back and forth over several other books before publishing Tom Jones, his masterpiece. These books tell in words what Hogarth had been painting in pictures with wildly popular series like A Harlot's Progress, A Rake's Progress, Marriage A-la-Mode and Industry and Idleness. Ostensibly moralizing work depicting how virtue is despoiled and vice ruins the feckless, they crowd their canvas with comic observations and sordid details and made Fielding the most vivid chronicler of life in England from the Acts of Union through the first Kings George.

Richardson works hard to bring Fielding to life in his picture, starting with a deer hunt that seems to involve the whole county, willing or unwilling. Cinematographer Lassally began with three handheld cameras capturing Tom and everyone in the local gentry quaffing and carousing as they prepare for the hunt as if it were a documentary film. It's barely controlled chaos – a collision of pictures and sound; since handheld cameras at the time couldn't record synced sound, Richardson assembled the whole sequence later, in editing.

But when the hunt begins it's chaos let loose and at speed, the action captured by a camera mounted just a couple of feet off the ground on a customized Mini Cooper, or from a helicopter soaring above the trees as it follows the hunt. Riders are thrown and bloody spurs gore the flanks of the horses, which charge through tenant farmyards and trample their geese and ducks. The deer is torn apart by the hounds before Squire Western prises it from their jaws, posing joyfully with the bloody carcass.

Griffith's Western embodies all the worst traits of the country squirocracy – a living rebuke to Rousseau's assertion that living closest to a natural state enables the best in a man. (Perhaps living on an island full of Squire Westerns inoculated England from Rousseauian notions later in the century when France succumbed bloodily to them.) His mortal enemy is his sister, Miss Western (Dame Edith Evans), who lives in London and spends her visits chastising him for his slovenly rural bumpkinry.

Evans was an actor, like Alastair Sim, who could elevate almost any movie she was in; as Lady Bracknell in Anthony Asquith's film of Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Ernest (1952) she was practically a special effect, and most people will remember the film for nothing more than her delivery of the words "A handbag?" Evans does very much the same thing here when she discovers her brother passed out on the floor in front of his fireplace in a pile of sleeping dogs and implores him to "Rise, sir, from your pastoral torpor."

Her visit from town triggers the first crisis of young Tom's life; he and Sophie had been drawing ever closer despite his inability to extricate himself from the arms of any woman within reach. For Tom, the narrator explains "any woman was better than none." Since she can't imagine that Sophie could conceive an affection for a prospectless bastard, Miss Western presumes that she's set her heart on the grasping, hypocritical (but socially appropriate) Blifil.

Aided by his equally grasping tutors Square (John Moffat) and Thwackum (Peter Bull), they expose Tom's continuing dalliances with the willing Molly and persuade Squire Allworthy to disinherit Tom and banish him from his home. This sets Tom on the road to London, and the picaresque and perilous "Progress" familiar to anyone familiar with Hogarth's paintings and engravings.

He meets a group of soldiers on their way to put down a Jacobite rebellion and inspired by Protestant patriotism and their camaraderie decides to throw in his lot with them. This was the British redcoat army a century before it started becoming professional; with regiments privately raised and officers with purchased commissions. In barracks or on the march they could be as destructive as an invading army. Writing about this scene in her biography Hogarth: A Life and a World, Jenny Uglow observes that Fielding:

"...shows a march of disarray, a parade of folly, a detached undercutting of military glory. Yet he is not so much disapproving as comically blunt – simply saying 'This is how it is.' And he also finds something admirable in the solders' frank display of lust and humour and sentiment – if you want to oppose Stuart absolutism and Catholic rigidity on the French model, you have the accept the near-anarchic freedom of the British crowd; their disorder is more valuable than it is frightening."

Tom's charm and naivete over dinner at an inn provokes the heinous Lt. Northerton (Julian Glover) to impugn Sophie's honour when Tom makes a toast to her, which leads to a brawl that leaves Tom on the ground, apparently dead, as Northerton and the rest of his company flee the inn, bills unpaid. Tom recovers, only to discover that the cash Allworthy had given him before sending him away is gone, so the landlady ejects him from the inn to continue his journey.

Further down the road he spies a woman (Joyce Redman) being tied to a tree by a British soldier – it's Northerton again, who turns out to be a sexual sadist as well as a liar. Tom comes to her rescue and turns out to be handier with his staff than Northerton is with his sword. The woman introduces herself as Mrs. Waters, and Tom agrees to accompany her as far as the next inn. She flirts with him outrageously and Finney, noticing the camera's rapt gaze on the travelers, breaks the fourth wall with a look of outrage and covers the lens with his hat.

The film's most memorable scene occurs over dinner at the inn that night, when Tom and Mrs. Waters sit down to devour endless courses of a meal. Soup, crab, chicken, lamb, oysters, pears and more are eaten as Richardson's camera cuts between Finney and Redman, who eye each other lasciviously over a supper that's obviously more like foreplay. It was neither in the book or the script but was developed by Finney and Redman during rehearsals and encouraged by Richardson. Nearly wordless except for sounds of biting and chewing, it's probably the distant ancestor of today's mukbang videos on TikTok.

Tom's progress on the road to London is followed closely by Sophie, traveling with her maid and then with her friend Mrs. Fitzpatrick (Rosalind Knight), who is herself escaping from her abusive Irish husband, and by Squire and Miss Western in their coach. Along the way Tom's misadventures leave behind scandalous stories for Sophie to hear, and Tom acquires a manservant when he comes across the country's worst highwayman – in fact Partridge, the barber, whose life was ruined when he was mistakenly credited with Tom's paternity.

Their arrival in London is carefully staged by Richardson to evoke Hogarth's famed pictures of urban squalor such as Gin Lane. His forlorn attempts to contact Sophie put him in the sights of her host, the seductive and sophisticated Lady Bellaston (Joan Greenwood), who kits him out in fashionable clothes and makes him her gigolo while trying to marry Sophie off with besotted older aristocrats.

Further improbable events and unfortunate meetings get Tom accused of robbery and attempted murder when he wins a duel with Mr. Fitzpatrick (George Cooper). He's on a tumbrel on the way to Tyburn when Mrs. Waters confesses to being Jenny Jones, which raises the spectre of incest for a moment until it's revealed that Allworthy's sister Bridget was Tom's mother all along; he's legitimized, his inheritance restored, Blifil is disgraced and Squire Western happily consents to his marriage to Sophie.

On the surface Richardson's film retains all the period trappings of a Georgian novel, but it was his style that turned Fielding's bildungsroman, which ends with everyone worthy around Tom receiving a pension or a living from the beneficent Allworthy, into something that played as restless and transgressive – a wild jab at breaking through the oppressive class limitations of Saturday Night and Sunday Morning.

Above all there's the sheer dynamism of Richardson's direction, which playfully draws on cinema history with audacious wipes and irises in and out of scenes, fourth wall breaks and scenes like Tom's escape from the in after being found in bed with Mrs. Waters, which Richardson had Lassally undercrank so it plays like a sped-up chase from a silent slapstick.

Compare the film to Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon, made just over ten years later. It's also set in Georgian England (and based on a William Makepeace Thackeray novel from 1840), but Kubrick went to great lengths to make his picture look like a Super Panavision camera and Steadicam had been transported to 1750. It's stately, even ponderous – two words you'd never use to describe Tom Jones.

There's the cast, who are uniformly superb, though you could have seen any of them in any combination in countless other British pictures at that time. Susannah York's Sophie, though, was fortuitous – she's lovely and fresh, especially compared to Diane Cilento's Molly, Joyce Redman's Mrs. Waters and Joan Greenwood, with her deep, hypnotic voice – a sultry sound from the era that preceded the one about to dawn. York seems contemporary by comparison, like she's got Mary Quant on under her bodice and petticoats.

(There's something very "Ginger versus Mary Ann" when you compare York with Julie Christie, her nearest equivalent. I know where my allegiances lie.)

But finally there's Finney, who would never look this young again onscreen. It was as if Tom Jones depleted his reserves of audacity and forced him to ration it for emergencies over subsequent decades, to be deployed only when it had the most effect. It's worth remembering that just seven years after making Tom Jones he would play the title role in another period picture: Scrooge.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.