The mark of successful satire is how well it anticipates future grim reality by playing current absurdities for laughs. Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove (1964), for instance, is revered because its riffs on the nightmare scenario of a cold war going hot continued to provide comic relief as the tense bipartite standoff lasted for another three decades. And while Mike Judge's Idiocracy (2006) flopped when it was released, its depiction of an ever-coarser culture enabled by plummeting IQs looks more prophetic with every TikTok craze and election cycle.

By comparison HBO's recent political satire miniseries The Regime sank without a giggle despite its excellent cast (Kate Winslet, Hugh Grant) and creators (director Stephen Frears, Succession writer and producer Will Tracy, former New York Times columnist Frank Rich). It was described as "not particularly funny, edifying, or insightful" by Entertainment Weekly while the Hollywood Reporter called it "blurry and self-evident" and having "little to say" but saying it "with a proud torrent of four-letter words".

Even the Guardian criticized the spoof of an unnamed post-Warsaw Pact autocracy as "groping for sense and meaning" and described it as a satire that "just doesn't quite know what it's supposed to be satirising." As ever these days, the best analysis of The Regime came from a YouTuber from Eastern Europe who said that it played out like a satire on political tyranny written by an AI bot – a lot of namechecking and Wiki steals that still didn't seem to be about anything real.

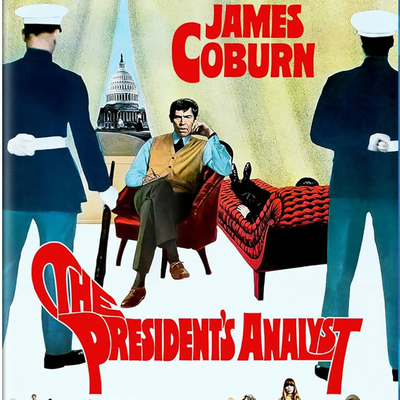

It's hard to tell today how the satire in The President's Analyst landed when it was released at the end of 1967. It's reputed to have bombed at the box office despite more than decent reviews; Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun-Times compared it favorably as a comedy to The Graduate and Bedazzled (two contemporary satires that time has treated very differently), but I can't read Ebert's affable review ("modern and biting, and there are many fine, subtle touches") without suspecting that he was swept up in the groovy zeitgeist, unwilling to go all squaresville and rain on the film's Technicolor parade.

Over subsequent decades, though, it blended in with so many other superficially similar movies, from the "zany" comedies produce by the major studios (It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines, Who's Minding the Mint?) to the countless 007-derivative spy spoofs (Casino Royale, Kiss the Girls and Make Them Die, Dean Martin's Matt Helm pictures, James Coburn's Flint films) to semi-credible attempts to capture the youth market (The World of Henry Orient, The Party, What's New Pussycat?) to wholly incredible ones (Way, Way Out, The Happening, Skidoo, I Love You Alice B. Toklas, Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine).

With time The President's Analyst has sorted itself into a small group of curiosities produced when major studios and minor hopefuls were dancing on the wreckage of the Production Code and trying to absorb some counterculture credibility – pictures like Bedazzled, The Magic Christian, Lord, Love a Duck and Putney Swope. In general, though, it's not an era that gets recalled as a golden age.

The picture begins by cutting back and forth between the office of Manhattan alienist Dr. Sidney Shaefer (James Coburn) and some scene of intrigue on the streets of the midtown Garment District. While Lalo Schifrin's very mod soundtrack plays, we see Sidney meeting with patients who range from depressed to boring to manic, while what looks like a document handoff between secret agents turns into a murder when a man pushing a garment rack sticks a knife into one of the spies, dropping his body into the box at the bottom of the rack.

The killer is Masters (Godfrey Cambridge), who doffs his disguise after hastily delivering the corpse to another pair of agents in a freight elevator, making excuses that he's late for an appointment with his shrink – Sidney. They begin their session with a breakthrough – a monologue where Masters recounts a dream about the moment he discovered racism, before confessing his profession and his murder of the day to Sidney, who wonders at how having the outlet of officially sanctioned homicide has relieved Masters of the lingering aggression and anxiety he sees in his other patients.

"Morality is a social invention," he pronounces, which gives you an idea of the world where all subsequent events will transpire. Masters goes on to another confession – that his role as analysand has been a ruse to vet Sidney for a job offer that could be the pinnacle of his career: psychoanalyst to the President of the United States. He has been under consideration for some time – his own analyst and mentor (Will Geer) was in on the process and extolls the great privilege of this offer while the two wander through an empty Whitney Museum.

The mentor asks Sidney his opinion of the modern artwork on display; Sidney says he likes everything, while the older man admits that none of it is to his taste. That's why he wasn't under consideration for this prestigious post. "You're a man of your time," his mentor tells Sidney.

When Sidney arrives in Washington the next day to take up his post and a home in posh Georgetown, he's led through an eerily empty Dulles International by the heads of the nation's top two security agencies. Cockett (Eduard Franz), the head of the CEA and Masters' boss, is WASPy and paternal while Lux (Walter Burke), the head of the FBR, is harsh and unfriendly, a malignant dwarf who objects to Sidney's live-in girlfriend Nan (Joan Delaney) as an immoral arrangement.

When we later see the heads of the two agencies meet with their staffs, the CEA is portrayed like a big extended family, men and women who look like they're spending the weekend at some compound on Cape Cod. The FBR, on the other hand, are a cohort of nearly identical men in black suits, short in stature, standing in formation while Lux gives them their orders, insisting that whatever they do, no matter how immoral, is in service to the nation.

There used to be a persistent cliché that while the CIA was composed of the second sons of establishment families and Ivy League washouts, the FBI recruited sharp strivers from Catholic universities like Fordham and Georgetown. This myth was obviously very much alive when The President's Analyst was made, which was also a time when FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover was prime among liberal America's ancestral villains.

The President's Analyst was the first production greenlit by Hollywood legend Robert Evans when he took over as head of Paramount Pictures, and he claims that he was visited by FBI agents who objected to the film's portrayal of the agency. He initially refused to make changes but gave in to pressure by the studio and ended up having to alter the names with dubbing in post-production. That is, of course, Evans' story, and you can believe it only as much as Evans would have wanted.

The film was the passion project of its writer and director, Theodore J. Flicker, whose name probably doesn't ring a bell. His sole film credits before making The President's Analyst were The Troublemaker (1964, and based on an improv by his theatre group The Premise) and the screenplay for an Elvis film, Spinout, though he did most of his work on television, writing and directing episodes of The Man from U.N.C.L.E., The Andy Griffith Show, I Dream of Jeannie and The Dick Van Dyke Show. He would later co-create the TV series Barney Miller and direct a movie version of Mordecai Richler's Jacob Two-Two Meets The Hooded Fang.

Flicker had met Coburn while visiting the set of Charade and ran into him again at a Christmas party where he told him about his script. Coburn brought the script to Evans, who made a deal to produce it in just five days. Coburn, who had already made his Flint spy spoofs for Fox, had just finished Waterhole No. 3, a comic remake of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and a bomb for Paramount. He needed a better film.

Coburn was a bit of an enigma; he could play a villain or a hero but his stock in trade was comic roles, where his gangly athleticism and cocksure manner combined to produce a sort of goofball hipster Lee Marvin. He's perfect for the role of Sidney, a man with appetites but no convictions, pulled through life in the orbit of more centred men like Cockett and Masters and Masters' opposite number and best friend, the KGB agent Kropotkin (Severn Darden).

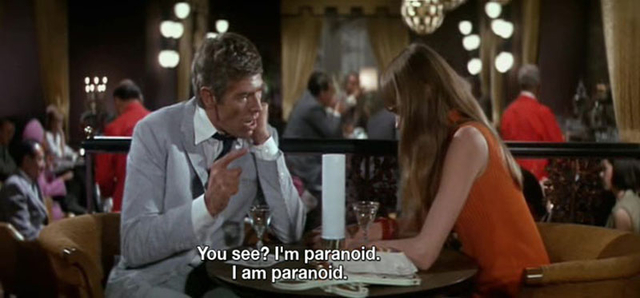

Sidney is quickly driven to nervous exhaustion by the President, who calls on him often, downloading the stress of his job on his shrink. He becomes paranoid, certain that everyone including Nan is spying on him. When Lux discovers that Sidney talks in his sleep he has Nan moved into a hotel where Sidney can only visit her during the day. Deprived of his only solace, Sidney escapes the White House by joining a tour group, attaching himself to the Quantrills, who describe themselves as "a typical American family."

Flicker invests quite a bit into his portrait of the Quantrills, who occupy a brief but vivid moment in his movie. Wynn (William Daniels) explains to Sidney that they're liberals, and proudly notes that they sponsored the first black family to move into their New Jersey suburb. He describes his next-door neighbour as a "real right winger": "American flag up every day. Real fascists. Ought to be gassed."

While his wife Jeff (Joan Darling) heads off to her women's karate class, Wynn scolds their son Bing for taking the magnum handgun out of his car's globe box – that's the car gun, and they have plenty of weapons in the house; he figures that liberals and right-wingers are going to get into a fight sooner or later so good liberals like his family ought to be prepared.

When Sidney excuses himself to make a panicked private call to Washington begging for help, the phone is tapped by Bing on his "Junior Spy Kit", and when his parents take Sidney into Manhattan for dinner ("chink" food; Jeff considers herself a gourmet) he calls the FBR, who thrill the boy when they tell him that they won't be taking Sidney alive.

While the CEA want to bring Sidney back, Lux has ordered his FBR agents to shoot to kill, and every other intelligence agency in the world considers Sidney a prize to be caught or killed. But when agents corner Sidney and the Quantrills outside a Greenwich Village restaurant Wynn coolly blows several away while his wife goes full Bruce Lee and karates them to the pavement.

Coburn's Sidney flees – anyone familiar with the actor will picture his stork-like run – and loses the agents pursuing him in the Café Wha?, hiding in a rock group's bus parked on the street. They offer to take him on the road with them upstate where he can get his head together, with the band's groupie Snow White (Jill Banner) taking a particular interest in the stressed-out straight.

Here's another cliché from movies of this period: the rock band cameo, often brokered by whatever record label was under a studio's corporate umbrella, inserted to bring youth into cinemas and maybe put a hit single on a soundtrack album. There was the Strawberry Alarm Clock in Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, the Standells and the Chocolate Watch Band in Riot on Sunset Strip, the Lovin' Spoonful in What's Up, Tiger Lily?, the Leaves in The Cool Ones and the Yardbirds in Blow Up. (Off the top of my head.)

For his film Flicker got L.A. psychedelic band Clear Light, augmented with "Eve of Destruction" singer Barry McGuire as "Old Wrangler", the presumed bandleader. They had recently been signed to Elektra Records and despite working with the team that made the Doors stars, they only managed to release an album and three singles before breaking up a year later. (Apparently the Grateful Dead had been offered the film but they turned it down; they'd end up in Richard Lester's Petulia a year later.)

The band make camp in a meadow full of wildflowers where Sidney takes on the protective colouration of velvet pants, a wig and sunglasses, whereupon Snow White takes him out to "smell the flowers." As they roll around in the grass McGuire writhes around on a hassock singing a song about "circles" and "changes."

What Sidney doesn't suspect is that the field is full of spies and assassins who try to dispatch him with garottes, crossbows, gas and poison darts, offing each other in turn before Kropotkin steps in finally, dressed as an Amish, to take out the last spy with a pitchfork. The camera pulls back as Sidney and Snow White stroll back to the band bus, unaware of the field full of bodies.

Coburn's Sidney might be the presumptive hero of the film but he's barely the protagonist. Sidney is a Candide character, reacting more than acting as he's nudged and pushed and chased through the story. The really dynamic characters are Masters and Kropotkin, the all-knowing yet ideologically diffident spies, whose friendship makes their roles at the tip of a global political conflict merely circumstantial.

The band meet up with another group, the 'Pudlians (complete with rubbish scouse accents), who dose everyone at their next gig with LSD, including the spies who've caught up with Sidney. But the 'Pudlians are really Canadian secret service (!!!), who politely abduct Sidney. He comes down and wakes up on a boat crossing the Great Lakes (actually John Wayne's yacht Wild Goose) but watches in horror as the FBR gun down the Canadians in cold blood, before in turn being taken out by Kropotkin.

Now the captain, Kropotkin tells Sidney that he's going to defect. It's no big deal: "Every day your country becomes more socialist, my country becomes more capitalist. Soon we shall meet in the middle and join hands." But before they can sail out the St. Lawrence to a waiting sub or tramp steamer, the Russian becomes the analysand and Sidney discovers enormous conflict – with his mother, a victim of Stalin's purges; with his father the master spy who turned her in – and Kropotkin decides that he needs to defect if only to continue his analysis.

Driving an Amphicar across the water to the shore, they hit a snag when a pay phone takes all their change before they can complete a call to Masters at the CEA. Kropotkin muses that, no matter where he's gone in the world, everybody hates the phone company. He takes the car back to town to get more change and leaves Sidney in the phone booth, which locks itself with him inside. A phone company repair truck arrives out of nowhere and takes the booth with Sidney in it, and suddenly we realize who the real villain of the story is.

The Phone Company.

It's worth remembering that when the film was made the Bell System, owned by AT&T, was a monopoly that was the sole phone provider in the U.S., including its subsidiary Western Electric, which made all its equipment, until it was broken up by the Department of Justice in 1982. Without competition they could set their rates at will, and anybody over 45 will remember the extortionate price of long-distance calls or feeding change non stop into a pay phone. (Since then a reconstituted AT&T has reacquired five of the seven "Baby Bells" created after the breakup.)

Sidney is taken to the sci fi Bond villain headquarters of The Phone Company (the film's producers were just as afraid to use the monopoly's real name as those of the country's security agencies) where he meets Arlington Hewes (Pat Harrington Jr.), the company chairman. Using a helpfully cheerful animated film, the affable yet sinister Hewes tells Sidney that the overhead necessary to run TPC has led them to develop a tiny microchip that can be implanted in every customer's brain, turning them into both a phone and an exchange.

The only obstacle is convincing the government to mandate the chips, and to make every citizen change their name to a number to make the system work. They just need Sidney and his intimate knowledge of the President to blackmail him into using his executive power to sign it into law.

But before they can bend Sidney to their will Masters and Kropotkin assault the complex in a commando raid and discover that Hewes is a robot. They need to buy time so the Russian can sabotage the phone network and make everyone in the country really mad at TPC, so Masters tosses an M16 to Sidney, who overcomes his pacifism in time to start mowing down security.

Suddenly it's Christmas and Sidney, Nan, Masters and Kropotkin are one big happy family, safe behind a closed-circuit security system in the Georgetown house. The President has used public outrage to force The Phone Company to lower its rates, and while a near-muzak version of "Joy to the World" plays the camera pulls back to show a room full of Hewes and his Phone Company robots blandly smiling as they watch our heroes celebrate on a big screen.

It's easy to complain that a film like The President's Analyst is frantic and implausible. But those are the hallmarks of satire, and without them you'd just have a topical but plotless comedy. It takes a moment to realize that the broadness and pacing has obscured how dystopian Sidney's America is: there are bugs and wiretaps everywhere, Nan turns out to be a CEA spy, and even young Bing Quantrill joins in what looks like a well-provisioned Stasi state, with surveillance for all.

What you have to acknowledge is how much of the film's satire lands, even if some of it took a few decades. There's the country dividing into militant factions right and left (again), Kropotkin's musing about the migration of socialism and capitalism, and almost everything about the Phone Company revelation, all of which might have elicited a shake of the head and a guffaw in the winter after the Summer of Love but looks eerily prescient in the age of smartphones rewiring our nervous systems with anxiety-provoking social media.

But let's play a little game: imagine you have a time machine and can go back to 1967 with a Blu-ray player and a copy of The Social Network, David Fincher's 2010 film about the birth of Facebook. Wouldn't they think it was a satire even more implausible than The President's Analyst?

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.