Any attempt to extricate politics from Warren Beatty's 1981 epic Reds is pointless. It has to be remembered that Beatty, who had wanted to make a film about the American journalist and communist John Reed since the '60s, finally sat down to write his first treatment of the story the night after George McGovern won the nomination at the 1972 Democratic Convention in Miami.

Beatty had worked hard for McGovern, and he locked himself in a hotel room for four days to produce his first draft of the story at the white-hot peak of a major spell of the star's political activism, campaigning for the progressive candidate and attending the convention. But it would take him nearly another decade to make the picture, by which point America's political climate had shifted considerably.

Reds, which went over-budget and over-schedule, was anticipated to join Heaven's Gate and Days of Heaven among recent and notorious big budget flops that nearly ruined studios. It was predicted that conservatives would stay away from the film and that leftists – already feeling marginalized in the wake of Ronald Reagan's election – would find no appeal in a Hollywood picture about the failure of early American communism and the squalid death of one of its figureheads. But Reds confounded these expectations and ended up making money and winning a dozen Oscar nominations. Why?

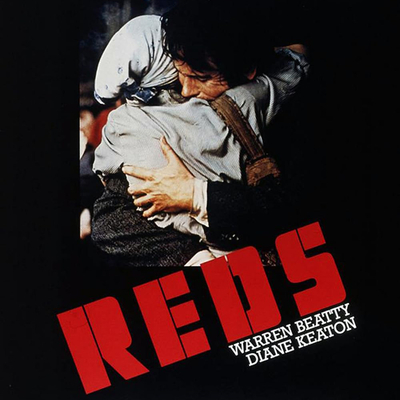

One answer is that when Reds finally came out in December of 1981, just in time to qualify for Academy nominations, it was being sold to the public as a love story, told as a historical epic – the sort of film that was thin on the ground the year that Superman II, Stripes and The Cannonball Run topped the box office. The love story between Beatty's Reed and Louise Bryant – played by Diane Keaton, the latest in Beatty's long list of high-profile girlfriends – was played up in the trailer and in the movie's poster and artwork, which showed the couple in a tight embrace, dressed in shabby period costume.

According to a 2007 Peter Biskind article in Vanity Fair about Reds, the film's working title during production was The John Reed-Louise Bryant Story (though one early draft of the screenplay Beatty wrote with British playwright and Marxist Trevor Griffiths was called Comrades). And anyone still settling into their seat for the picture's three-plus hour runtime would only get a brief glimpse of Beatty's Reed in a long shot on a dusty desert road during the Mexican Revolution, running to catch up with a group of armed men in a horse-drawn cart.

It's Keaton's Bryant who we get to know first – a dentist's wife in Portland, Oregon who fancies herself a writer and artist, causing a scandal at an art gallery opening in 1915 when friends discover that she'd modeled for a discreet nude study hanging on the gallery walls. Reed catches her eye when he returns to visit his widowed mother and gives a speech at the local Liberal Club on the war – a single word when the windy, jingoistic worthy who introduces him asks why they're fighting in Europe: "Profits."

She buttonholes him after his speech and brings him to a little garret room she keeps for her artistic activity, away from her home by the water. She neglects to mention a dentist husband, and her attempt at an interview with Reed – at this point an accomplished and respected journalist – inspires a coffee-fueled political rant that lasts all night and into the morning. She flirts with him just enough to get Reed to agree to look at her writing, then leaves.

They meet again at a pointedly stuffy dinner party full of ancient older friends and family, all very prosperous and dull. (Reed was a product of privilege, the grandson of an industrialist and a Harvard alumnus.) He mocks her for being so bourgeois as to marry a dentist, but she retains the upper hand, casually inviting him to have sex on the ground outside a church while he walks her home. ("I'd like to see you with your pants off, Mr. Reed.")

What follows is a contest of identities as much as will; they conduct an affair inspired by the ideals of "free love" as it was espoused by self-styled radicals in the early decades of the last century. He asks her to leave her husband and come with him to New York – to Greenwich Village, the Emerald City of bohemian life, and she agrees, arriving to find a note on the door of his walk-up apartment: "Property is Theft – Walk in."

In his book Reds: McCarthyism in Twentieth-Century America, Ted Morgan portrays Bryant as a glamourous creature, the sort of woman a man of destiny like Reed would choose as a companion. He introduces her at a pro-Russia rally in Washington, DC in 1919, her "delicately lovely, vibrant-eyed face...shaded by a wide-brimmed hat."

He describes the couple appearing at a subcommittee on Bolshevism chaired by Democratic Senator Lee Slater Overman (at which Beatty only shows Bryant testifying while Reed works on Ten Days That Shook the World, his bestselling account of the Russian Revolution):

"Here at last were the bohemian revolutionaries, back from their appointment with history, the radical playboy, initiated into the class struggle by way of Mabel Dodge's Fifth Avenue Salon, and the willowy beauty who had been Eugene O'Neill's muse. There was almost too much colliding charisma between them. Reed, the big-boned, florid-faced man of action, and Bryant, headstrong and impulsive, doggedly unconventional, who had deserted her husband, an Oregon dentist, for a more exciting life."

It's hard to know how much Morgan's book, published in 2003, was influenced by the portrayal of Reed and Bryant in Beatty's picture, but you can't help but speculate based on his choice to give it the same title as the movie. Reed had been called a "playboy of the revolution" by no less than novelist Upton Sinclair, and director Sergei Eisenstein's October: Ten Days That Shook the World (1927) was based on Reed's book.

John Dos Passos would write about Reed in 1919, the second book of his U.S.A. Trilogy, and the couple would appear in Sergei Vasilyev's post-Stalin drama about the Bolshevik Revolution, October Days (1958). This would keep the legend of Reed and Bryant alive long enough for Beatty to discover it as an ambitious young actor; a wildly romantic story that inevitably stands out amongst party intrigues, famines, battles between ideologues, and the descent of revolutionary zeal into tyranny.

At first things are rocky for the new couple. She feels overlooked among his dynamic and radical friends, which include his editor Max Eastman (Edward Herrmann), notorious anarchist Emma Goldman (Maureen Stapleton) and playwright Eugene O'Neill (Jack Nicholson). Bryant is relegated to being merely Wife of the Great Man, insubstantial in her own artistic ambitions, and of only sexual interest to men like Whigham (George Plimpton), a publisher and Harvard classmate of Reed's.

They try to make a new start by moving to an artistic colony in Provincetown, Massachusetts where they can be poets as well as journalists, and help found the Provincetown Players with O'Neill. (I'm aware that this column has turned into a space to bag on Eugene O'Neill before, but the brief scene from his early play The Dancer we see rehearsed with Keaton's Bryant in the title role does nothing to diminish a long-growing consensus that O'Neill's reputation was wildly overhyped.)

Keaton plays Bryant in these early scenes as defensive, increasingly resentful but only in private with Reed, who's baffled by her complaints; she comes across as a vaguely emancipated bourgeois woman, very much an ancestor of her Oscar-winning role in Annie Hall four years earlier, while Beatty brings facets of Clyde Barrow, George Roundy in Shampoo and Joe in Heaven Can Wait to Reed – a man baffled and energized at the same time by the events of his life as it spirals well past his ambitions.

The emotional crux of the film is the romance that develops between Bryant and O'Neill during that idyllic summer by the shore, a liaison that would become part of Bryant's abiding reputation, which starts when Reed continues to neglect her, and goes off to cover the Democratic political convention, intent on seeing Woodrow Wilson keep his promise to keep America out of the war.

Beatty didn't plan to do more than produce his movie about John Reed at first, and at one point saw John Lithgow as Reed – a much closer physical resemblance. Trevor Griffiths was never sure of this while working on the script with Beatty. "Warren spoke as if he was the reincarnation of Jack Reed," Griffiths told Biskind for his Vanity Fair article. "Reed was a golden boy. I would get that sense as we talked that Warren had been born to play him. Or Jack Reed had been born so that at a later moment Warren could play him!

For O'Neill, Beatty had imagined singer James Taylor or even Sam Shepard in the role – men whose gaunt, haunted looks were closer to the notoriously alcoholic playwright. But he eventually thought his friend Nicholson more suitable for the part, and according to Biskind Beatty tricked him into taking the role. "I told him I needed someone to play Eugene O'Neill, but it had to be someone who could convincingly take this woman away from me," Biskind recalls Beatty telling an interviewer, to which Nicholson responded, "There is only one actor who could do that – me!"

This was just as Nicholson was finishing filming on The Shining, and Beatty worried that he'd let himself go too much for Kubrick's picture, and the role that would set the benchmark for Nicholson's manic performances for the rest of his career. One of the marvels of Reds, in fact, is watching Nicholson stuff his oversized persona into the rigid confines of O'Neill, giving us glimpses of his sarcasm and rage only when required.

Upon discovering the affair, Beatty as Reed pulls out his trademark charm and convinces Bryant to not only get married but move into a little cottage in Croton-on-Hudson, one of New York's picturesque bedroom communities. A long romantic montage follows, with the couple enjoying domestic and creative bliss, complete with Christmas trees and a labrador puppy; the only threat is Reed's increasing involvement in Big Bill Heywood's Industrial Workers of the World, the anti-war movement and his failing kidneys.

I have lost track of all the people I have known who insisted that monogamy is a bourgeois concept and that infidelity is not just natural but inevitable. And like nearly all of them we watch Reed and Bryant suffer with both jealousy and a principled inability to admit how strongly they feel betrayal. (Beatty pal Elaine May is credited with the dialogue between Reed and Bryant.) Given Beatty's renown as a cocksman in the pro-level Hollywood leagues, it's interesting how crucial this is to the protagonists of Reds, and the scene between Bryant and O'Neill, when she visits him in Greenwich Village after Reed has left for his third and final visit to Russia.

Nicholson's O'Neill finds it hard to refrain from questioning their motives, and delivers an excoriating monologue with characteristic contempt:

"You and Jack have a lot of middle-class dreams for two radicals. Jack dreams that he can hustle the American working man, whose one dream is to be rich enough not to have to work, into a revolution led by his party. And you dream that if you discuss the revolution with a man before you go to bed with him, it'll be missionary work rather than sex. I'm sorry to see you and Jack so serious about your sports. It's particularly disappointing in you, Louise. You had a lighter touch when you were touting free love."

This is especially trenchant as the argument they have, before Reed leaves for what would be a fatal trip, plays out like two people calling each other's bluff when they're at their most emotionally vulnerable. If she hadn't been so incoherently angry at his offhand admission of cheating on her, he might have considered staying in America, in their cottage with their adoring dog and Reed's secret dream of starting a family with Bryant. But they're trapped by their ideals, and Reed sets off for the gaping maw of Bolshevik Russia, promising to be home for Christmas.

Stalin did not like John Reed, and despite writing an introduction to Ten Days That Shook the World, Lenin did not like the prominence Leon Trotsky played – accurately – in Reed's story of the Bolsheviks and the October Revolution. George Orwell claimed that the British Communist Party, who were given the copyright to Reed's book in his will, tried to destroy original editions of the book and released their own edited version that cut out both Trotsky and Lenin's introduction.

This was the Russia that was taking shape when Beatty's Reed returns to the country, intent on getting Comintern recognition for his own splinter American communist party, which had formed in opposition to another, more immigrant-focused party when they were expelled from the American Socialist Party. (If you've spent any time adjacent to leftist politics, this will be a familiar story. If you've spent time in conservative politics over the last three decades, you'll recognize it appearing and repeating with dismal frequency.)

The October Revolution and the fall of Kerensky's provisional government is the climax (literally) of the first half of Reds. Reed and Bryant are firsthand witnesses to the Bolshevik coup and find themselves drawn into the cause irrevocably; we even see Reed finally find his voice as an activist addressing Russian crowds, as Keaton's face moves from dismay to muted joy – a fantastic performance. The couple follow the torchlit crowds marching through the streets at night, write reports on the situation in a frenzy, and make love in their dingy Petrograd apartment while the Internationale builds on the soundtrack just before the film's intermission.

(Beatty insists that Reds was the last film released into theatres with an intermission.)

When Reed returns alone things are changing just as quickly but not as hopefully. Lenin and the Bolsheviks have no interest in recognizing either American communist party and insist they unite. Central power is coalescing around the party executive and Reed's biggest opponent is Lenin's right hand man Grigory Zinoviev (played by writer Jerzy Kosinski, before the plagiarism scandal and fall from grace that would lead to his suicide in 1991. Zinoviev would fall victim to Stalin's show trials and was executed by the NKVD in 1936.)

When he manages to slip through the blockade around Russia, Reed finds a country beset by civil war, lineups for food, the threat of famine and increasing political strife after the Bolshevik victory. He ends up sharing digs with Emma Goldman, recently deported from the U.S. thanks to new anti-dissent laws (and apparently seen off at the dock by J. Edgar Hoover.)

When we meet Stapleton's Goldman in Greenwich Village, she's brusque and off-putting, apparently allergic to compromise or conciliatory language, quick to verbally kneecap anyone using platitudes or cant. "I think voting is the opium of the masses in this country," she says. "Every four years you deaden the pain." (I have to admit that Stapleton reminds me of my friend Kathy Shaidle, late of this column, who began her political life – some of us think she never left – an anarchist like Goldman.)

She sees more clearly than Reed where things are going in the new Soviet Union, and says that whatever it takes she's getting out. Still desperate to believe, he says that they're fighting a war and that every weapon is needed including "terror and firing squads".

"It's not happening the way we thought it would," Reed tells her. "It's not happening the way we wanted it, but it's happening."

"Nothing works," she replies. "Four million people died last year. Not from fighting a war, they died from starvation and typhus in a militaristic police state that suppresses freedom and human rights where nothing works."

"Jack, I think we have to face it. The dream that we had is dying in Russia. If Bolshevism means the peasants taking the land, the workers taking the factories, Russia's one place where there's no Bolshevism."

And Goldman could not have known that the numbers she cites would get worse – much worse – in the ensuing century, wherever systems like Bolshevism would rule millions of people.

At this point Reds becomes truly epic, with Reed detained as a useful propagandist for the party and unable to return to Bryant, while Bryant makes an epic voyage – across the ocean in a tramp steamer, across arctic forests, through war zones – to get to Reed. Here, as elsewhere in the film, cinematographer Vittorio Storaro's camera work is magnificent.

Comparisons between Reds and later masterpieces by David Lean like Doctor Zhivago and Lawrence of Arabia were made as soon as the film was released, and they're hard not to see in the scenes where Reed and Bryant struggle alone through the snow on either side of the Finnish border, or in the long sequence where Reed is sent by the Comintern to promote revolution in the middle east at a conference in Baku.

He passes through White Russian outposts and arrives to find a Babel of voices shouting over each other at the conference, then discovers that Zinoviev has changed his incitement of "class war" in his speech to jihad or "holy war" in the translations. He confronts the top apparatchik about it on the train, shouting at him like he did at Gene Hackman's newspaper editor early in the film that nobody changes his words but him.

"You separate a man from what he loves most, what you do is purge what's unique in him," Reed shouts at Zinoviev, apparently on the verge of understanding just what the party expects of men like him. "And when you purge what's unique in him, you purge dissent. And when you purge dissent, you kill the revolution! Dissent is revolution!"

It's as fine a moment as any to punctuate a revelation, and suddenly the back of the train behind Reed explodes when the Whites begin an ambush. A line of White cavalry attacks from over the horizon with Red cavalry hurtling down ramps from inside the train to meet them. It's the closest to Lean that Beatty is able to get, and his Reed – increasingly ill as the film comes to an end – jumps up from the track bed to go off running after the horsemen, like we first saw him in Mexico at the start of the picture: a man of action in pursuit of same.

Bryant's reunion with Reed was short; he would die of typhus in a Moscow hospital and is one of just four Americans buried in a place of honour at the wall of the Kremlin. Bryant had a heart attack by the gravesite at his funeral. She met William Bullitt, an executive at Paramount, while pitching him a movie based on Reed's book; they married and Bullitt would become US ambassador to the Soviet Union, after he divorced her in 1930 citing Bryant's alcoholism and infidelity. She died in Paris in 1936, the last year of Bullitt's ambassadorship.

Emma Goldman suffered a stroke and died in 1940 in my hometown, Toronto. Reed's editor and friend Max Eastman would begin a gradual political about face after visiting the Soviet Union, refuting Marx and many of his previous idols. He became an editor at Reader's Digest and is mentioned approvingly in Friedrich Hayek's The Road to Serfdom. He was a founding editor of the National Review but left the magazine's board when he said it had become too Christian.

Years later, the most intriguing part of Beatty's film are the "witnesses" – the friends, colleagues, enemies and contemporaries of Reed and Bryant who are interviewed against a stark black backdrop, and whose testimony opens the film, some obviously struggling to recall the couple after decades, admitting that both time and memory have made them unreliable.

The witnesses' interviews were a masterstroke by Beatty, who wanted to avoid excessive exposition by his characters, and decided to give the job to people who were actually there. They aren't identified by name but get listed in the roll call at the end of the credits and include people like entertainer George Jessel (filmed wearing his USO uniform), writer Dame Rebecca West, historian Will Durant, Alexander Kerensky's son Oleg, journalist Adela Rogers St. Johns, novelist Henry Miller and Hamilton Fish, the famously anti-communist congressman and Harvard classmate of Reed.

Miller is particularly ribald and mischievous. (He apparently asked Beatty to get his young girlfriend, one Brenda Venus, a part in the picture in exchange for the interview.) Asked what he thought of Reed, Miller finds an echo in Jordan Peterson and says that "I think that a guy who's always interested in the condition of the world and changing it, either has no problems of his own or refuses to face them."

Not surprisingly Beatty's relationship with Keaton was nearly over by the time shooting ended, but Keaton was adamant that their relationship had nothing in common with the Reed and Bryant they portrayed onscreen, telling Biskind that "I don't think that we're that important, historically, Warren and I. Sorry to say."

For his part, Beatty was adamant that it was a political film and not a romance. "What moved the late '60s and '70s was politics," he told Biskind. "Reds is a political movie. It begins with politics and it ends with politics. It was in some sense a reverie about that way of thinking in American life, one that went back to 1915."

"We were those old lefties that were narrating this movie. We, me. Reds was a death rattle."

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.