What will be the blockbuster movies of Summer 2024? Entertainment Weekly published a list at the beginning of May, which was helpful provided you eliminate mere summer releases (I Saw the TV Glow, Babes, Firebrand, Inside Out 2, The Watchers, Janet Planet, Despicable Me 4, The Instigators, Kinds of Kindness, Fly Me to the Moon, It Ends With Us, The Bikeriders, Blink Twice, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice) and everything being released on streaming (Atlas, Hit Man, Ultraman: Rising, Trigger Warning, The Union, Beverly Hills Cop: Axel F, The Instigators, Jackpot, Appollo 13: Survival).

Which leaves a much smaller group of big budget action films and spectacles (almost totally free of MCU [Marvel Cinematic Universe] content, it must be noted) aiming to entice us into theatres and make the top of Variety's box office charts: Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga, Bad Boys 4: Ride or Die, Kevin Costner's two-part western Horizon, MaXXXine, Transformers: High Moon, Twisters, Deadpool & Wolverine, Alien: Romulus and The Crow. A lot of remakes, reboots and sequels, very few original ideas, and every one of them arriving with big production and marketing budgets that need to be made back.

I can only speak for myself, but who cares? Every summer arrives with at least a half dozen hopeful blockbusters grasping for our dollars, like beggars in designer clothes. And I'm old enough to remember before films presented themselves with such audacity; a time when movie studios assumed that we preferred to spend our summers on vacation, at the cottage or the beach, when the weeks before and after Christmas were when you booked big budget productions in every movie palace and neighbourhood theatre that would show them.

It was a long time ago, and it all ended with a movie about a fish.

But what was happening at the beginning of the summer of 1975 that made us so desperate for distraction? Well, the Watergate trials were finally ending with sentencing and imprisonments, and that episode would get capped with the release of All the President's Men in theatres a year later, freeing baby boomers to forget Nixon and start thinking about real estate and the stock market. South Vietnam was conquered by North Vietnam and the Khmer Rouge took over Cambodia, but since Nixon ended the draft two years earlier nobody but veterans seemed to care much, and the "domino theory" was yesterday's political rhetoric.

When June began, Israel removed its tanks and troops from the Suez Canal, the UK voted to stay in the European Community, the Soviets sent the Venera probes to Venus, Pelé signed with the New York Cosmos, the first crude was pumped from the North Sea oil fields and Sam Giancana was shot before he could testify in front of Congress.

A day later Jaws opened nationwide. It made its budget back two weeks later and by the first week of September it had outgrossed The Godfather, and it would sit at the top of the all-time box office records (unadjusted for inflation) until Star Wars unseated it two years later. The film's production woes had been in the news for much of the previous year, with stories about malfunctioning mechanical sharks, plus budget and schedule overruns. (A 55 day shoot schedule ballooned into 159 days.) It was presumed that Jaws would tank and probably end the career of its young director, Steven Spielberg – best known for a hit TV movie (Duel) and a modestly successful crime picture (The Sugarland Express) – before it had really begun.

That alternate future died with the film's opening scene. As if bringing the summer outside the theatres onto the screen, we're on a beach where a group of young people are sitting around a campfire entertaining themselves with the tools of the pre-digital age – a harmonica and a guitar, some weed and beer. On the edge of the crowd a tussle-headed young man is eyeing a girl (stuntwoman Susan Backlinie) sitting on the outskirts overseeing a boiling pot. She eyes him back, then suddenly gets up and runs off down the darkened beach.

He follows her, the pair flirting breathlessly as he tries to keep up with his quarry (or is he hers?) as she starts shedding clothes. It would be years before I was able to pick up on the wardrobe clues, in particular his khakis, deck shoes and sweater – a Norwegian crewneck in blue with broken white diagonal stripes that's been a standby in the L.L. Bean catalogue for decades. When we meet the boy again in the glare of the morning sun we get a concise precis of his background in three place names: Hartford, Trinity College, Greenwich.

His family are from the island; he's renting a house with four friends for a hundred bucks each a week plus food and booze. It seems like a lot of money but he says it "isn't bad." The girl – her name is Chrissie – is from off the island, a "summer dink". I would have missed all of this as a boy, but adults familiar with the social cues of east coast beach towns would understand a whole seasonal class system in a few lines of dialogue.

But before we get to those cues we're sole witness to the fate of poor Chrissie. While Tom the tussle-headed boy (Jonathan Filley) collapses at the water's edge, a victim of beer and the ocean air, she plunges joyfully into the dark still water and swims out to a buoy, but before she gets there we hear the two ominous, low dissonant notes of John Williams' justifiably famous theme. The camera moves from bobbing on the surface next to Chrissie to below, looking up, from the point of view of something terrible.

It nips at the girl, then grabs her, dragging her screaming in agony like a rag doll to the buoy and back while the boy naps on the tideline. After a scant but terrifying minute she's pulled under one last time and audiences were firmly under the spell of the first real summer blockbuster.

And so Jawsmania began. In his book Blockbuster: How Hollywood Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Summer, Tom Shone writes about the summer of the shark:

"A Jaws discotheque opened in the Hamptons, complete with a wooden shark; a Georgia fisherman started selling shark jawbones for $50; a New York ice cream stand renamed its staple flavors sharklate, finilla, and jawberry; a Silver Spring specialty dealer began selling strap-on Styrofoam shark fins, for anyone who wanted to start a mass panic in the privacy of their own beach."

But even more notably:

"...up and down the coast towns of America, hotels reported a spate of canceled bookings, as people caught wind of the sudden rise in reported shark attacks: which is to say, commercial interests lost actual money because of the release of Jaws. So much for synergy. In fact, the official Universal merchandising was minimal – T-shirts, beach towels, posters – and when Spielberg proposed a chocolate shark, he was turned down – the first and last time in the career of Steven Spielberg that he would be refused a merchandising opportunity by a studio."

I didn't see Jaws the summer it was released, but it was impossible to escape. Growing up in an inland city on a freshwater lake, I've never seen an actual shark outside of an aquarium, but there were serious conversations among my friends – prompted by actual news stories – about whether it was possible to get bitten by a rogue shark in Lake Ontario, or even at Muskoka Beach.

For a few months, or at least until the water at Sauble or Crystal Beach got too cold or we went back to school, it seemed the whole world had become Amity, the Long Island summer town where we meet Martin Brody (Roy Scheider), the cop who had taken the job as Amity's chief of police, seeking to escape the accelerating decay of John Lindsay and Abe Beame's New York City.

Revolutionary as it might have been, Jaws is still a '70s movie, and anyone who was alive and conscious – or young, more to the point – will begin their flashbacks from the moment we see Brody wake up the morning after the first shark attack next to his dishy wife Ellen (Lorraine Gary, wife of Universal CEO Sidney Sheinberg). They're hung over, and he complains about how the sun shines directly into their bedroom window.

"We bought the house in fall," she reminds him. "It's summer."

Their boys, Michael (Chris Rebello) and little Sean (Jay Mello), are already up and outside, as typically emancipated as any child of the time, bothered by only fitful parental supervision, and Michael has already learned how to barter for extra privileges based on how distracted his parents are. Then Brody gets the call that takes him out to the beach, to where Tom has reported a missing, presumed drowned Chrissie.

But they find her – or what's left of her, though all we see is a pale white hand emerging from a pile of feeding crabs in the grass by the dunes. Brody the city cop gets to work, swimming against the small-town lassitude, reporting a shark attack based on the town doctor's advice, moving swiftly to close the beaches before the maneater feeds again.

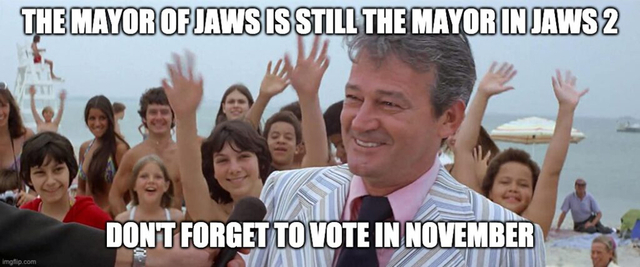

But before the days is over he's ambushed on the town's little car ferry by a quartet of town leaders, including the doctor, the publisher of the newspaper and Mayor Vaughn (Murray Hamilton), who's concerned that Brody is acting rashly. The mayor has pressured the doctor to revise his diagnosis from shark attack to boating accident, and at a town hall meeting where locals protest the loss of crucial summer business, he learns that his beach closure has been reduced to a temporary one of just 24 hours.

The last time I wrote about Jaws – and it's just one of two Spielberg films I love to write about – I said that "as much as I enjoy Jaws, and as many times as I've watched it, I usually lose interest or fall asleep sometime after the three men on the becalmed boat hunting the shark start comparing scars. This isn't a knock at Steven Spielberg's direction, or the performances of Roy Scheider, Richard Dreyfuss and Robert Shaw, but a reflection of my opinion that Jaws isn't really about a shark."

Much as I think Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T. aren't about aliens as much as they're about the decaying nuclear family on the downward side of the sexual revolution, I think Jaws is about the loss of trust in politicians and public institutions in the wake of Watergate and the perpetual protest movements of the '60s.

The Peter Benchley novel that inspired the movie was even more downbeat, with the mayor involved with the mafia and Brody's bored wife having an affair with the marine biologist Hooper – a WASPier character in the book than in the movie. I quoted a British journalist, James Kidd, writing about Jaws in The Independent in 2014: "Benchley's shark is an amoral force of nature: not bad, just hungry. And what amoral nature has unleashed, so amoral nature reclaims in death. As Brody swims home, the inference lingers that Amity, not the ocean, is home to genuine evil: corruption, selfishness, infidelity, lies, fury and greed."

Or as Shone writes in Blockbuster, the film "told two stories, only one of which happens to be about a giant shark. The shark eats the girl, then the boy; but then look what happens: the town reacts as if school was out. It erupts into a boomtown of petty profiteering and casual lawlessness; kids start scrawling graffiti on billboards; bounty hunters head out to sea in a big crazy flotilla, shooting guns into the water; and Spielberg is on fire..."

"Spielberg's fascination with the echo-chamber of the mass media circus receives further amplification in Jaws; the bounty hunters come back with a shark that does get their picture in the paper, and the next thing you know the story has gone national. The national networks arrive, and are soon crawling all over the beach with their cameras, just in time to catch the next shark attack, which turns out to be a hoax: two small boys, wearing a wooden fin, who are pulled, dripping from the water. If you want a trenchant analysis of Jawsmania, in other words, your best bet has always been to check out Jaws itself. It's all there, up on the screen – the hysteria bleeding into hoopla, the hoopla into hype, and the hype into hoax."

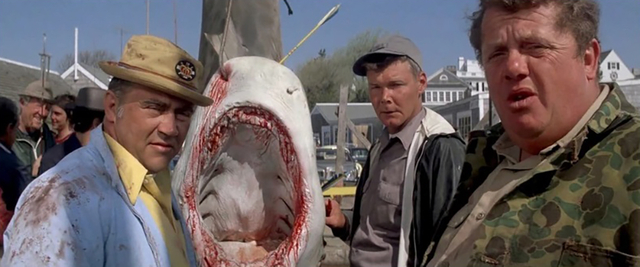

In the year leading up to the release of Jaws the media coverage was obsessed with what was going wrong with the picture, but when it was released we learned just how much had gone right. There was the casting, starting with Scheider as the cop who's afraid of the water. And there was Richard Dreyfuss' Hooper, a considerable revision from the character in Benchley's novel, and the lynchpin of the trio of "heroes" who go on the quest that comprises the last half of the movie.

From the moment he's pulled up onto the dock in the middle of the frenzy of local fishermen and sportsmen drawn to the island by the promise of a bounty on the killer shark, he plays the misfit rebel – the nebbish who seemed to stand in for Spielberg himself for two consecutive films. Shone writes that "Dreyfuss' reaction times – the flash flood grins that light up his face, the octave-vaulting scat of his line readings – are the second fastest thing in the movie, and from the moment Dreyfuss set foot in Jaws, he told audiences all they needed to know about how different a movie this was going to be."

His Cooper – a scruffy rich boy self-funding his obsession with the ocean's top predator – is allowed to be flippant and sarcastic where Brody needs to be diplomatic. He chuckles that the boat loads of nitwits heading out to hunt the shark are "all going to die!", and he gets in the face of Mayor Vaughan when he browbeats Brody into keeping the beaches open for the all-important Fourth of July weekend despite two deadly attacks.

When dismissed as a dilettante and city boy by the grizzled local shark hunter Quint (Robert Shaw), Cooper sputters that "I don't need this working-class hero crap," but he's the emollient that creates a bond between the three men when they're out on the water hunting the shark, and he's the only one who knows the significance of Quint sailing on the doomed USS Indianapolis on its final voyage.

And there's Shaw's Quint – a walking caricature of the salty dog that Shaw nonetheless makes watchable, inspiring even, with his irrepressible misanthropy and radiant hostility. Fans of his performance need to watch the film's deleted scenes, which includes Shaw visiting Amity's music store to buy three reels of piano wire for his deep-sea fishing rod. He's sweetly polite with the young woman running the shop, then hunches down behind a boy trying to play "Ode to Joy" on his clarinet, menacingly humming, then bellowing out the melody until the poor lad breaks from the strain.

I'm still a little bored by the shark hunt in Jaws, but with every screening I've come to love the dynamic that grows between Scheider and Dreyfuss and then Shaw, as they're forced together out to sea on the Orca, the only men in Amity who know what they're doing and, more importantly, why. Their temporary bond, Shone writes, was echoed by audiences who watched Jaws not once but many times over that summer.

Unlike recent big hits like Love Story and The Godfather that kept viewers solitary, "Jaws united its audience in common cause – a shared unwillingness to be served up as lunch – and you came out delivering high-fives to the three hundred or so new best friends you'd just narrowly avoided death with. And then you came back the next day to narrowly avoid it again."

Even the secondary cast is full of vivid little performances, like the gravel-voiced local businesswoman in the lacquered beehive who owns Amity's hotel, and the daftly menacing giant local fisherman who greets Hooper on the jetty. Murray Hamilton's mayor is a truly worthy villain – the small man with more power than he deserves, driven to near-catatonic contrition by his complicity in his town's tragedy. He was such an indelible character that he was as essential as Scheider to the film's inevitable sequel, and which give birth to one of the internet's more abiding memes:

(The problem with this meme is that there's every reason to believe that the Mayor was reelected because everyone did vote in November. I live in Canada, you see...)

But you have to credit Spielberg with most of the film's success, the budding movie brat genius with the right story, cast and tools to announce his arrival; smart enough to realize that the near-constant malfunction of his principle special effect – a trio of unreliable mechanical sharks that never worked as expected – demanded he minimize its appearance onscreen, while forcing him to find his scares with editing that built real suspense. (A lesson we have forgotten in an age of miraculous digital effects.)

Just as summer box office reaches the peak of anticipation with the Fourth of July weekend, Spielberg's film builds to a crescendo of chaos when Amity fills with tourists for the holiday, arriving on packed ferries from the mainland, on bikes and on foot, in station wagons and Rolls Royces, heading for ancestral family homes, summer rentals, weekend motel bookings or nights sleeping rough in the dunes.

Brody has called in reinforcements who ring the cordoned beach in boats, and even manages a helicopter to patrol from the air. But the crowd – doubtless swollen with morbid interest in the maneater lurking offshore – is still unwilling to leave their beach blankets and lounge chairs. Mayor Vaughn circulates through the crowd cajoling the locals, finally convincing one elderly couple to head out clutching their air mattress and the hands of their grandchildren.

They begin a slow exodus off the beach and into the water, while Brody pleads with his oldest son to take his little sailing skiff and his little brother out to the pond where the "old ladies" take their boats. Spielberg cuts between the shore and the crowd in the water, Brody with his walkie talkie and the armed men patrolling the deeper water outside the cordon until a fin in the water triggers a stampede.

I've come to suspect that the lull in suspense that makes me lose interest in the last half of the film is because Spielberg leaves behind the inherent conflict that builds from the moment a hungover Brody leaves his house, forced by duty and a paycheque to deal with his new neighbours and the visitors who invade the island intent on leisure or a bounty on the first shark they can kill.

Because the misanthropy that infused Benchley's novel still managed to survive in Spielberg's film and would have been more abundant if the director had chosen to keep his much longer version of the first shark hunt in the picture – a melee of armed idiots in tiny boats crossing each other's wakes and fighting to claim the carcass of the luckless tiger shark that blunders into their path. It's a dismal vision of a citizen mob that goes a long way to explaining how men like Mayor Vaughn end up anywhere from the town hall to the Senate or beyond.

But its most perfect vision is in the water during that stampede to safety, when panicked families on holiday trample each other, men throwing children off air mattresses as they rush for safety, elderly swimmers pressed into the shallow surf under the feet of strangers and neighbours. In one spectacular shot a mother screams as she clutches a child in water churned white by the mob rushing for the beach while a helicopter roars past behind her.

This nightmare resonated with audiences – massive, avid ones – back in that watershed mid-'70s summer, probably because we'd all gotten a glimpse of how much resentment and suspicion lingered beneath a fraying polity. Spielberg's film staked out a spot right between the dark, "intelligent", putatively radical visions of Coppola, Hal Ashby, Scorsese, Altman and Bogdanovich and the big budget thrill rides that would make his career, along with his friend George Lucas and other movie nerds like James Cameron and Robert Zemeckis.

But for a while, with films like Close Encounters, Ridley Scott's Alien and its James Cameron-directed sequel Aliens, we could believe that a spectacle could also feature compelling characters who weren't amplified to the scale of a film's action scenes. As Shone writes in Blockbuster, "now we knew, and would never go back, willingly, to the old system of cinematic apartheid that had existed before, dictating that popular movies must be dumb, and highbrow films boring. Spielberg had upped the game for everyone."

But it wouldn't last – just look at the Jaws sequels. The wild success of the first film meant the inevitable Jaws 2, which brought back Scheider to regret his part in a hypertrophied remake of the first film by a far lesser director (Jeannot Szwarc). Spielberg was briefly involved in a Jaws prequel around this time, which would tell the story of Quint and the USS Indianapolis. You can't help but wish that it had not just happened but had quenched his thirst to make a World War Two film and, ultimately, spared us 1941.

And then there was Jaws 3-D, which I was unfortunate enough to see (not in 3D) in a drive-in outside Cobourg, Ontario, and which is only redeemed by comparison with Jaws: The Revenge, about which the less said the better. And here we are, faced with another summer of putative blockbusters, most of which seem conceived in the same spirit as Jaws 2. It makes you want to stay out of the dark and spend your summer at the beach.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.