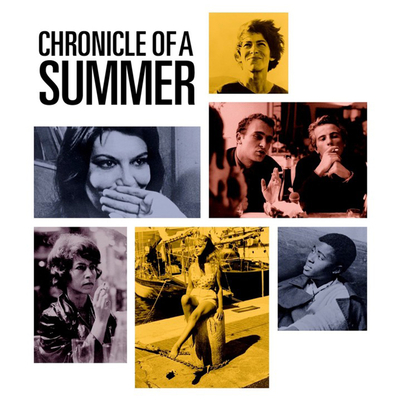

The term cinéma vérité has been around for so long that we forget that somebody had to come up with it, but the phrase was coined by one of the two filmmakers who released an award-winning and ground-breaking documentary, Chronicle of a Summer, in 1961. For a scorching first week of summer (at least here in Ontario) it seemed a good time to revisit this very period, very provocative, very French picture, which broke from film conventions and anticipated a coming social upheaval.

The phrase cinéma vérité was invented by co-director Jean Rouch and the film's publicist, and its simple meaning – "truthful cinema" is the most accurate translation – promises an awful lot. Rouch, a filmmaker and anthropologist, and his partner Edgar Morin, a philosopher and "sociologist of the theory of information", decided to make the film when they served on the jury of a film festival in Florence, and were inspired by new documentaries like Karel Reisz's We Are the Lambeth Boys (1958).

While Morin was the more political and intellectual of the pair, Rouch was the filmmaker, and the directors were aided by new technology in the form of the Nagra tape recorder – a (relatively) small and light machine that synced sound with equally portable silent film cameras. This allowed them to make their film out on the streets with a "walking camera", and for a while they toyed with describing their method as "pedovision".

It's a good thing that word never caught on.

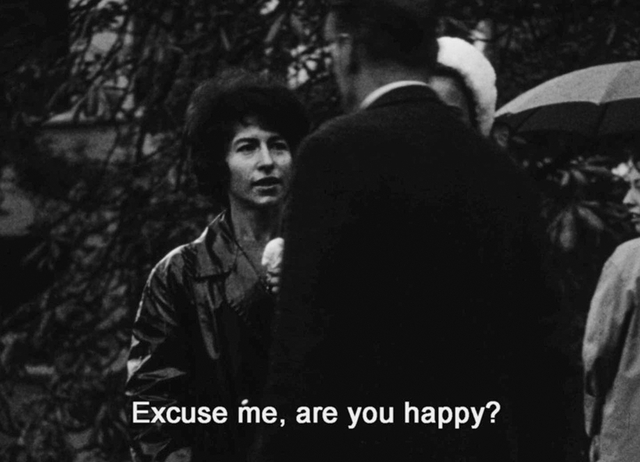

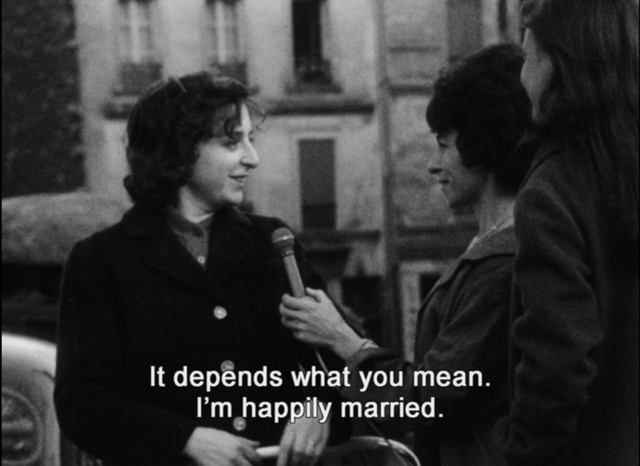

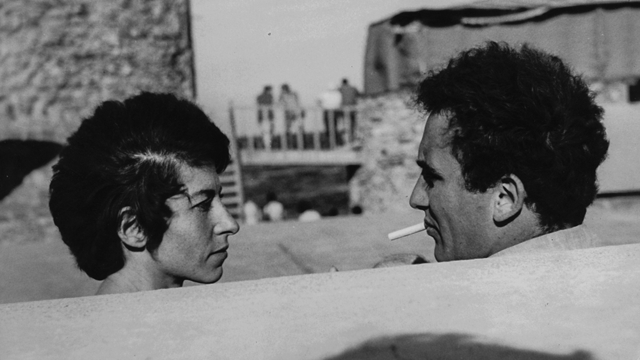

Their filmed interrogation of Parisians in the street was led by two women: Nadine Ballot, a pretty young student, and Marceline Loridan (born Rozenberg), a handsome woman in her early thirties who was working for a polling service transcribing interviews. The film begins with the two of them doing what we used to call "streeters" or "man in the street" interviews, stopping passersby and asking them questions like "Are you happy?"

At first they get brushed off, with startling hostility, but soon their targets are stopping to talk to them with candour. Sometimes their answers are blunt but honest – "A worker is never happy" says one woman – but they hit the jackpot with a mechanic and his friends who say their work makes them happy but confess that much of their work and income is off the books and under the table. "No one could manage if they stuck to the law," they tell them.

The film began with titles on the screen telling us that what we're going to see was "made without actors but lived by men and women." We are meant to understand that what we're going to see is honest and real, but it all begins with a bit of a lie.

The scenes with Nadine and Marceline interrogating random Parisians was shot not at the start of the film but very near the end, after most of what we see subsequently had been filmed and edited. In a documentary included with the Criterion edition made to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the film in 2011, we see the two women being coached by the filmmakers on how to use the Nagra recorder and what to ask the passersby they'll be collaring as they leave Metro stations and workplaces.

"You're bubbly and pretty, it'll work out great," they're told. "Be nice and flirty."

There is, no surprise, an awful lot of talking. It's a French film, you're thinking to yourself; four people sitting around a table full of empty plates, glasses and coffee cups is the French cinematic equivalent of a car chase. And there is smoking. A lot of smoking. If you're old enough you can smell this film.

And from this point on the people the filmmakers encounter aren't random as much as they've been drawn from the social networks of friends and acquaintances. We meet a young couple, bohemians living in the classic garret, who talk about their half-serious but often disappointing moneymaking schemes like faking antiques, and insist that they really don't care about getting ahead in what they see as a consumer society.

Then there's an older couple, intellectuals judging by the loaded bookshelves behind them. They had slept rough in parks when they were younger, during a long postwar housing shortage in Paris, but now they've found an apartment – social housing in Clichy, in the city's northwest quarter, and hopefully not Clichy-sous-Bois to the northeast, now one of Paris' more troubled districts – and have a child. Bourgeois circumstance has overtaken them; can bourgeois lifestyle be far behind?

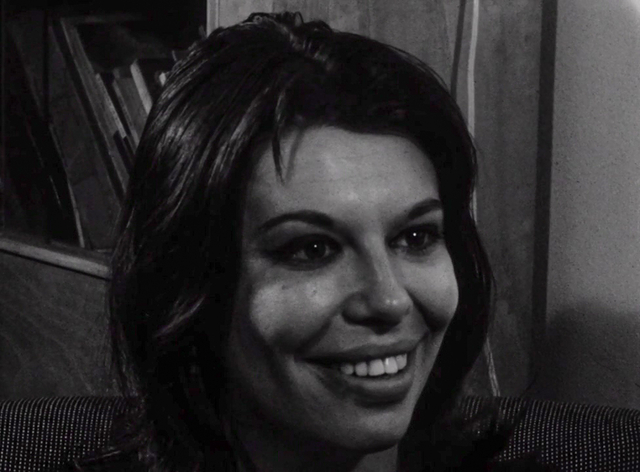

And there's Marilu, a 27-year-old who emigrated from Italy to create a life separate from her middle-class family. She's living in an attic flat with no water or heat and says that she's been losing herself in "drinking and sleeping around." Her depression is palpable and her interview is probably the most poignant in the picture, as she tries – and fails – to keep her emotions in check and tells us that "I don't even have the right to kill myself. It would be phony."

Her testimony is the most personal so far, but from this point the film widens out to take in the political context that clearly interests the filmmakers. So what was happening in the months leading up to the summer of 1960 that would concern men like Rouch and Morin and their circle of friends?

There were border clashes between Indian and Chinese troops that left twelve Indian soldiers dead, the Sharpeville massacre in South Africa, a military coup in Turkey and the covert approval by US president Eisenhower to train paramilitaries for an invasion of Cuba. America sent a contingent of 3,500 troops to Vietnam, the youngest son of the Peugot automaker family was kidnapped for a $300,000 ransom, and Adolf Eichmann was abducted from Argentina to stand trial for war crimes in Israel. Francis Gary Power's U-2 spy plane was shot down over the Soviet Union.

In Africa there was a wave of nations achieving independence from European colonizers: Cameroon, Togo, Mali, Senegal and Madagascar splitting from France and Congo freeing itself from Belgian control, triggering the Congo Crisis and a civil war whose early victims included white settlers killed by nationalists. And at the forefront of the minds of most young French men and women was the Algerian War, which had been going on for six years by the summer of 1960.

We meet young men – students who are worried about being drafted to fight in Algeria, including Jean-Pierre, Raymond, and Régis. What we're not told is that Jean-Pierre Sergeant was part of the "Jeanson network" working actively against France's war efforts, and with groups directly supporting the FLN. This was effectively treason, and Sergeant would escape the country for exile in Belgium after being filmed by Rouch and Morin.

(Régis was Jules Régis Debray, a Marxist philosopher who taught at the University of Havana and was captured in Bolivia where he traveled with Che Guevara to support guerilla rebels. He was sentenced to a 30-year prison term but released in 1970 after appeals to the Bolivian government by no less that Charles de Gaulle and Pope Paul VI. Debray moved to Chile but returned to France after the coup by General Pinochet. He became an advisor to President François Mitterrand on foreign affairs.)

This reflected orthodox thinking among younger members of the filmmakers' social circle. "We were a bunch of bourgeois intellectuals stewing in our Parisian-ness," as one of the former students says in the documentary made fifty years after filming. They admit that their pro-third world stance came from reading Sartre but that, practically, the Congo was "far away" and their concern probably wasn't very sincere.

"Most students are idiots," they say. "They don't know how to talk to people."

And so the film shifts focus to representatives of the working class like Jean and Angelo, and the Renault plant, where the camera takes in the details of remarkably grimy and dangerous-looking work at ancient machines, and workers eating lunch at their stations in a suddenly silent factory. (By comparison an auto assembly line today looks more like a medical lab, with employees in obligatory safety gear.)

Rouch had spent much of his career making films about Africa and Africans, so he brought in some of the cast from his previous film, The Human Pyramid, and specifically Landry, a student from Cote D'Ivoire. The filmmakers engineered a meeting between Angelo and Landry to demonstrate the sort of camaraderie that a good leftist would have wanted to see between constituents from the groups they imagined would be crucial to any Marxist revolution in a first world country like France.

And the two men do seem to hit it off genuinely, though Angelo ends up doing most of the talking – explaining might be another way to phrase it – during their filmed interaction. (It's hard not to interpret the scene as a controlled experiment by the anthropologist Rouch.) Angelo, we learn in the documentary, was regarded as an "enlightened" worker by the filmmakers – an autodidact who we see reading serious books on the couch of his mother's house after he works out in the tiny yard.

Anyone from a working-class background can't help but watch all of it and anticipate how this relationship would eventually end, when the political left lost its patience with "proletarians" and their tendency to "false consciousness" – that is to say a refusal to assume the goals and definitions imagined for them by enlightened betters.

But the most abrupt shift in tone happens when the camera returns to Marceline and the numbers tattooed on her arm. Landry and his African friends are intrigued by the numbers – is her father a sailor, or is that her phone number? When she explains that it's because she's Jewish, and that the tattoo was given to her after her family was deported to Auschwitz, Landry sheepishly says that he had, of course, seen Alain Resnais' Night and Fog (1956) but that he had never made the connection.

This is followed by a long scene, a reverie of sorts, where Marceline walks alone through the Place de la Concorde and a mostly deserted Paris in the morning, recalling to herself how she had briefly met her father again after a year in the camps, and that he had told her prophetically that while she will survive, he would never return home.

There was still a strong aversion to confronting the truth of the Holocaust and the French role in it; even Night and Fog notably only mentions Jews once, in a list of victims of the camps. In a bonus feature included with the Criterion disc of Chronicle of a Summer, Marceline is interviewed on the waterfront at Cannes for a French TV show in 1962. She talks about her deportation, about the Eichmann trial, and about the doctor doing the selections on arrival at the camp. (Joseph Mengele, apparently, though she doesn't say his name.)

The interviewer responds by asking Marceline if talking about these things isn't an "exhibitionism of the soul." In a New Yorker story about the film, Richard Brody describes this as "evoking the very social codes that made such discussions so rare." It wouldn't be until Marcel Ophuls made The Sorrow and the Pity in 1969 that France and the French were able (were forced, in effect) to confront their political and personal culpability in the Holocaust.

This self-censorship is embedded in the whole of the film. Press censorship in France was rampant during the Algerian war; newspapers could be confiscated from newsstands for criticizing the government and the military, and the army tortured not just Algerian prisoners but their French supporters. Jean-Luc Godard's 1960 film Le Petit Soldat had been banned by the government and its producer threatened, so Rouch and Morin had to be prudent about what made it onscreen in their picture.

(It's easy to forget that the birthplace of modern democracy and republican government has always had its own particular definition of just what comprises liberté – and that quite a lot of the meaning of the word gets lost in translation, across the Channel or across the Atlantic.)

As if seeking to lighten the tone, the film returns to Marilu, who has been utterly transformed in the two weeks since she was interviewed, coming through what sounds like an emotional breakdown and emerging with new, unimagined hope. She has met a man, and while we get a glimpse of him in a scene where he visits her workplace and criticizes Antonioni's L'Avventura ("I prefer virile filmmakers" he says), we aren't told that he's new wave director Jacques Rivette, who Marilu had met when the filmmakers got her a job at Cahiers du Cinema.

(Rivette would marry Marilu Parolini and while they later divorced, she would still collaborate with him, as a co-writer and set photographer. Marilu died in Italy in 2012.)

This triggers a shift in location as the film – like most of Paris – picks up and heads south for the last month of summer. There are a few scenes showing Angelo and other workers with their families climbing rocks near what we presume are campgrounds where the French working-class summers, while the rest of the cast and crew head to St. Tropez.

We see Landry and Nadine on the beach and at a bullfight and are introduced to Sophie – a model and starlet who makes money in the summer by posing with and for tourists with cameras, the kind of buxom, blonde living souvenir who once embodied the French ideal of summer on the Mediterranean coast.

Bonus material on the Criterion disc includes footage that shows Marceline and Jean-Pierre talking their way through an agonizingly slow breakup while on vacation. It's riveting to watch, but the filmmakers were right to cut it out; it does play more like a dramatic film than a documentary – you could easily imagine something like it in a film by Eric Rohmer.

(Marceline Loridan would marry the famous Dutch left-wing documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens in 1963. Ivens worked briefly in Hollywood during the war, assisting Frank Capra on his Know Your Enemy: Japan picture in his Why We Fight series until Capra had to fire him for being too sympathetic to the Japanese. Ivens and Marceline would move to Vietnam and make 17th Parallel: Vietnam in War, before leaving for China where they made the 12-part, 763-minute long Cultural Revolution propaganda film How Yukong Moved the Mountains, but had to flee China when they landed on the enemies list of Mao's wife, Jiang Qing. Ivens would receive the Order of the Netherlands Lion from Queen Beatrix in 1989, just before he died. Marceline died in Paris in 2018, at 90.)

The film concludes in a screening room where the filmmakers show their assembled footage to their subjects, but it doesn't go well. One of them says he found it hard to believe that Angelo found any common ground with Landry; another says that Marilu's first, long bleak interview felt like a performance. Another one says that it was all "painful" when it wasn't "boring."

The two men film themselves walking up and down the hallway of the Musee de l'homme, clearly stung by the reaction and trying to understand if they'd succeeded or failed with their film. "We're questioning truth which is not everyday truth," one of them says. "We've gone beyond that." As Morin would later write:

"I thought we would start from a basis of truth and that an even greater truth would develop. Now I realize that if we achieved anything, it was to present the problem of truth."

While the film they made and the reaction of their cast might have felt like a failure, their decision to include this little struggle session at the end would end up being inspirational for future documentary filmmakers (Errol Morris, Werner Herzog, Joshua Oppenheimer) who were less pained about establishing truth. Their film provided ample context for what was coming in French politics and society – May 1968 and soixant-huitards like Debray who would end up at the controls of the country – and has made lists of top ten documentaries ever since.

You can't help but feel sorry for them, fretting over their responsibility to truth and their thwarted attempt to capture it in an hour and a half of film. They weren't the first and won't be the last ones who began by making a mistaken assumption. After all, ever since Pontius Pilate asked "What is truth?" we've confused it with "What is good?" and "What is real?" Or more specifically "What makes sense to me?"

But there I go sounding like a Frenchman.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.