The American west has always seemed to be, at least as portrayed in western movies, a terrible place. This might be purely subjective – I also consider every science fiction film a kind of dystopia, and the world of the modern rom com an extension of high school (which is to say a circle of hell). But I was reminded of this once again while watching Anthony Mann's 1953 film The Naked Spur, one of five westerns Mann made with James Stewart, all of which are considered crucial revisionist or "psychological" westerns.

There are only five characters in Mann's film, and they all point guns at each other upon meeting – an apparently prudent thing to do in the Colorado Territory and its adjacent pre-statehood expanses of unsettled frontier. A stranger is as likely to be an enemy as a friend – more so, considering the circumstances in Mann's film. And given how wild and unpeopled the territories straddling the Rockies were at the time, a body left in the open might never be found.

And then there's the landscape. Mann made a point of filming many of his westerns far away from the southwestern deserts favoured by John Ford and the arid coastal plains a convenient few hours' drive from Hollywood. The scenery is beautiful – they justifiably call this part of the United States "God's country" – but it's pitiless if you're in the open and on foot; rocky and steep, and full of river canyons that rage after rains and winter melts.

I'll let you decide if you'd prefer to fall off a horse into sand or down a vertical cliff face into white water rapids. A desert is dry, but water can be as deadly as it is essential. In any case I'd rather travel across Rocky Mountain National Park on Route 34 with air conditioning than traverse it with a pack mule, unsure if there's giardia in that clear mountain stream.

The film begins with Mann's camera taking in the scenery and resting on the spur on a man's boot before he heads toward a snow-capped mountain peak on a trail through the forest. (Every trail in The Naked Spur seems to head toward yet another mountain peak.) Kemp (Stewart) pulls a gun when he comes across a prospector tending to his campfire and tells him to keep his hands in the air.

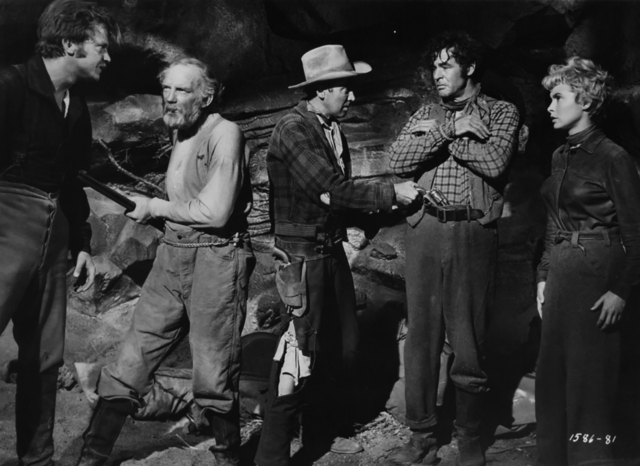

Tate (Millard Mitchell, almost unrecognizable in a grizzled beard and costumed in full Gabby Hayes mode) doesn't seem to consider this much more than local custom, and calmly talks Kemp into letting down his guard – or at least holstering his revolver. Kemp is on the trail of a fugitive; he shows the prospector the wanted poster and the old man assumes that Kemp is a marshal or a sheriff.

Kemp offers Tate $20 to help him track his quarry and, given the perpetual gig economy of the frontier, the prospector is happy to take it. The wanted man, Ben Vandergroat (Robert Ryan), killed a marshal in Abilene, Kansas, and they eventually find him at the top of a high stone outcrop, triggering rockslides on anyone trying to approach him.

The shooting attracts Anderson (Ralph Meeker), recently discharged from the US Cavalry – a dishonorable discharge that his papers attribute to being "morally unstable." Anderson is jovial and cocky; he describes himself as a great Indian hunter and says his departure from service was due to an incident with the daughter of a chief. This front loads Meeker's character with too much bad karma to imagine him still breathing at the end of the last reel.

Kemp explains the situation and Anderson cheerfully agrees, with dubious motivation, to help. Kemp tells Tate to pin Vandergroat down with rifle fire while he scales the outcrop to surprise him from behind, but he's unable to make it up, so Anderson takes on the challenge, surprising Vandergroat, who has company – Lina (Janet Leigh), the daughter of Vandergroat's best friend, killed while robbing a bank.

They take Vandergroat into custody, but the outlaw quickly discerns that Kemp has let his companions assume that he's a lawman and not just a mercenary bounty hunter, after the $5000 reward on Vandergroat, dead or alive. The stakes have been raised; Tate returns the $20 to Kemp and the situation turns into a partnership, with Anderson and the prospector forcing themselves on Kemp for a share of the bounty. They only have to get back to Kansas – the closest outpost of actual law and civilisation – without killing each other.

If you were trying to cast a criminal intent on saving his skin in the '50s you'd find Robert Ryan at the top of your list. Like Mann, Ryan made his name in film noir, most notably as the anti-Semitic psychopath in Edward Dmytryk's Crossfire (1947), and he'd go on to a career of morally compromised or outright evil men in films like Clash by Night, Billy Budd, Bad Day at Black Rock and The Wild Bunch.

We can thank Robert Ryan for the compelling villains and anti-heroes of today; the actor brought skill and relish and – there's no other way to put it – a real sense of joy to playing killers, racists, bullies and creeps. His Vandergroat is playful and wry despite his predicament; there are some critics who insist he steals the film from Stewart. He has a sociopath's keen judge of character and weakness and sets about sowing division between his captors from the moment they bind his wrists together.

But their captive isn't the first big problem facing Kemp and his posse. They soon discover that a party of Blackfoot are on their trail, or rather that of Anderson, whose relationship with the chief's daughter was more along the lines of rape. They tell him he has a head start and that if he outrides his pursuers they'll meet up with him later – a bad deal, but the only one he's got.

The group eventually stops and faces the Indians across a forest clearing; Kemp and their chief are signaling a truce when Anderson, hiding behind a log, opens fire. Westerns toying with revisionist themes in the '50s made awkward but palpable attempts to sympathize with Indians who lost land, history and agency during westward expansion; it might take years to really humanize them onscreen, but it was the sign of a lowly b-movie oater if it relied on the trope of the whooping horde of mounted warriors in war bonnets and face paint descending on the remote fort or stagecoach.

Sadly, though, the Blackfeet of The Naked Spur are still victims of a venerable western cliche – they're typically poor shots, and worse tacticians; even with two of their party disarmed, Kemp, Tate and Anderson still manage to slaughter a dozen warriors at the cost of a single slug in Kemp's leg. And even then the wounded bounty hunter pulls himself back into the saddle, stopping to survey the clearing full of bodies with a pained, regretful shake of his head before they ride on.

While Kemp is the nominal leader of the group, the only one who actually knows anything about him is Vandergroat, who hoards the knowledge until it's useful. When his wound makes him feverish he talks in his sleep, mistaking Lina for his wife, Mary. Vandergroat tells them that he'd signed his ranch over to his wife before leaving to fight "to preserve the union" – Ryan makes sure those words are loaded with just a hint of dismissive scorn.

But his wife sold the ranch and ran off with another man, and Kemp returned to find himself homeless. The bounty on Vandergroat is meant to help him buy his land back, but it won't be enough split three ways, and their captive uses that information to push a wedge further between the three men.

Vandergroat works on Tate by talking about a big gold strike he knows about. The old prospector has been searching for riches since at least 1849, going wherever there's news of a strike and finding nothing. He confesses his lifelong failure to their captive one night, revealing a deep well of shame and greed twisted together that Vandergroat knows he can use.

The morally centerless Anderson is an easier mark, and he taunts the rapist with Lina, knowing that the other men will find his interest unseemly. Despite her reliance on him and his constant shows of affection for her, Vandergroat admits that there's nothing physical between them, and that he considers their relationship more paternal, though that doesn't stop him from using her to play with Kemp's loneliness and shame after being cuckolded and betrayed.

As for the voluble, ceaselessly upbeat Vandergroat, he muses that his fate was probably sealed when his parents died on the westward exodus, leaving him alone to fall in with bad company on the lawless frontier. It has left him with a keen eye for failure, and Ryan's captive uses it with a skill you almost have to admire, enhanced with the bottomless charm that's almost inevitably bundled with the sociopath personality.

If anything motivates Stewart's Kemp it's a quality that Mann showcases in the actor's roles across their westerns – a propensity for sudden, manic violence fueled by a deep wellspring of hate and anger. This is so at odds with the persona the actor created at the start of his career – the lanky, affable idealist of You Can't Take It with You, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, The Shop Around the Corner and The Philadelphia Story.

But it's a persona Stewart himself seemed intent on dismantling from the moment he returned from wartime service in the air force, starting with the desperate, resentful and occasionally raving George Bailey in It's a Wonderful Life, and continuing through his films with Mann and Alfred Hitchcock (Rope, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Rear Window, Vertigo). By the time he made The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) with John Ford, Stewart had transformed that persona, though practically that younger man, so easy to caricature with the stutter Stewart turned into a sign of integrity, persists to this day.

"He had a great way with violence," Mann said about Stewart, quoted in K. Austen Collins' essay about Mann and Stewart's westerns on the Criterion website. "Most people don't realize that about him, but when he was mad about something, when he had been wronged in a film, when he showed anger, it was much more intense than in most actors. He could be extremely volatile."

Starting with the titular cursed rifle in the vengeance tale Winchester '73 (1950), Mann confronted audiences with Stewart's capacity for wild-eyed violence. His protagonist, Lin McAdam, is barely able to control it until he comes across a colleague of Stephen McNally's villain in a saloon and forces information from him.

Collins writes that there's "something in McAdam's eyes: a pent-up aggression that seems to broaden as we watch, widening – like McAdam's eyes – from an expression of impersonal, practical frontier violence into something that's harder to name, something like pleasure, something shocking. There's a discomfiting hunger in it. We expect our western heroes to leave needless violence behind, just as – we think – McAdam has."

"We expect virtue to curb recklessness. The great heroes of westerns are often men who, with wars and countless personal battles trailing them like shadows, come off a bit wary, a little spent. They're often looking for a way out, and the movies needn't even tell us what they're looking for a way out of for us to know that it is better left to the past. Hunger, we associate with villains or misguided youth: bloodlust is for the lost."

Sheltering from a stormy night in a cave, Vandergroat gets Lina to distract Kemp so he can escape out the back, but Kemp frantically pulls him back inside, where his "partners" insist that their captive is too much trouble alive and that the reward is the same for a corpse. Pushed to his limit but unwilling to kill a man in cold blood, Kemp challenges Vandergroat to a quick draw, but the wanted man pleads that he doesn't stand a chance after days with his hands tied together.

The whole scene plays like a cruel parody of that western standby – the duel in the bright sun on a wide dusty street, but performed in the dismal confines of a cave, one man reasonably unwilling to take part in a contest he knows he's going to lose.

With Kemp wounded and weak Vandergroat has an opening, and he covertly loosens the buckle on his captor's saddle before pushing Kemp off his horse and down a cliff, but the bounty hunter's fall is broken by some trees. He painfully pulls himself back up the cliff to the trail while his companions sit in their saddles and watch; with everyone's weaknesses teased into the light by Vandergroat there are no friends here, and even Lina is ashamed of her passivity.

Later, their way blocked by a river swollen in the spring run-off, Anderson says "He's not a man, he's a sack of money," forcing the awful truth into the open. There's an ugly fight between Kemp and Anderson, both men brawling in the dust as their companions look on. By the end of the film it seems that nobody wants anyone else to make it to Kansas alive, though they'd rather someone else did their dirty work for them.

It is, Collins writes about the Mann/Stewart westerns, which also include Bend of the River, The Far Country and The Man from Laramie, "as if these men were mere flakes in a snow globe, tracing the same, contained arcs, trapped in each other's orbits until one or all of them die."

What makes The Naked Spur so much more vividly cruel is the small, ensemble cast and a growing claustrophobia in spite of the majestic landscape setting. It's the closest Mann's westerns get to the austere economy of Budd Boetticher's westerns during the same period.

By the time the credits roll there's just two characters left standing – the same pair you might have expected at the start – and an ending that, while undeniably bleak, promises something like redemption. The film did well, making back double its budget for MGM. Ryan would work with Mann again on Men in War (1957) and God's Little Acre (1958), but it would be Millard Mitchell's second-to-last picture; the actor died of cancer eight months after The Naked Spur was released.

Mann and Stewart's westerns would be critically well-regarded. Writing about The Naked Spur in The Encyclopedia of Western Movies, Phil Hardy calls it "extraordinary"; he calls Stewart "the most neurotic of Mann's heroes" and says Mann's direction "relentlessly strips the characters of their self-justifications and self-deceptions until they stand naked."

Not everyone was so enthusiastic: writing about the film in The Western from Silents to the Seventies, George Fenn and William Everson judge that while Winchester '73 was "an extremely satisfying horse opera", the subsequent films with Stewart were let down when "the pretentiousness and the artifice showed through the gay surface of the prints."

All I know is that despite Mann's deliberate pacing, the superb performances and breathtaking scenery, I was grateful when the final credits rolled and I was able to escape the pitiless moral hellscape of this particular vision of the frontier.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.