For the first time in a long time we are living in a world without James Bond. Despite having been promised that Agent 007 would Live and Let Die and Die Another Day, when the last film in the Bond series was released in 2021 and despite telling us that it was No Time to Die, Daniel Craig's 007 perished in the villain's lair at the end of the film, under a salvo of missiles fired by his own Royal Navy.

The only people who seem to have found this satisfying were Daniel Craig and producer Michael G. Wilson, and it didn't go over well with fans. (It's still the only Bond film I haven't seen.) But it's not the end of Bond; as one of the most successful movie franchises in history, there's no way it was the last we'll see of Agent 007.

Esquire UK recently published an article running the odds on all the contenders for the inevitable Bond reboot. It's a long and fascinating list of likely lads (Henry Cavill, Tom Hardy, Idris Elba), interesting suggestions (Barry Keoghan, Andrew Garfield, Chiwetel Ejiofor) and absolute improbabilities (Harry Styles). But whoever gets picked we've been assured repeatedly by everyone with a say in the matter that it will be a new Bond for a new era, with everything that implies.

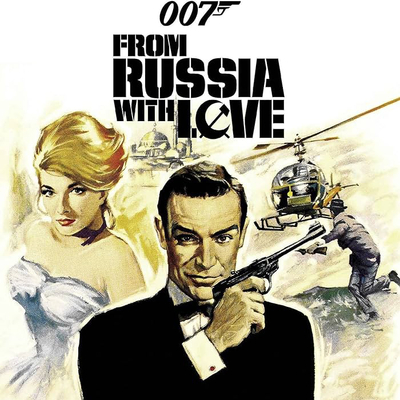

Which is why, in these troubling times, I find it comforting to go back to a very early Bond, when the man and his movies were still struggling to find their form. From Russia with Love was the second film in the 007 series, released in the UK almost exactly a year after Dr. No had been the huge hit producers Albert "Cubby" Broccoli and Harry Saltzman needed to fulfill their promise of a Bond a year.

The film begins, after the iconic "gun barrel" intro recycled from Dr. No, with the death of James Bond. In the first cold open of the series we see Sean Connery's Bond in his tuxedo creeping through the shadowy formal gardens of a vast country estate at night. He's being shadowed by a big blonde man dressed in black (Robert Shaw); Bond knows he's there and is clearly spooked, shooting recklessly into the darkness before the man pulls a wire garrotte from his wristwatch and throttles Bond dead.

A bank of klieg lights suddenly illuminates the scene, which is apparently some bad guy training exercise. A rubber mask is pulled off the tuxedoed corpse to reveal a man with a moustache, and the baddie in charge congratulates Shaw's killer for his excellent time in dispatching this disposable stand-in. Cue Monty Norman's theme music, with the credits projected over the undulating limbs and torso of a belly dancer.

The film proper begins with an international chess match in the vast ballroom of some palazzo in Venice; the Czech Kronsteen (Vladek Sheybal) is toying with his Canadian opponent until he gets a message delivered on a coaster under a glass of water, calling him to a meeting. He dispatches the Canadian with Boris Spassky's checkmate of David Bronstein from a 1960 match in Leningrad, then makes his way to a luxury yacht anchored in the lagoon where his faceless, nameless boss in the SPECTRE terrorist organization meets him and recently-defected Soviet espionage chief Rosa Klebb (Lotte Lenya).

It's all very on point for the 007 films we would know and love; the Great Game and all of its double- and triple-crosses, setting Bond against a suitably repulsive cast of SPECTRE villains. The lizard-like Kronsteen has come up with a plan to steal and then ransom a top-secret Soviet decoding machine by playing MI6 and SMERSH against each other, and Klebb has been assigned to run the operation on the ground, using SPECTRE killer Red Grant (Shaw) as her muscle and weapon.

Lenya's Klebb is built to be a particularly memorable Bond villain, with a broad streak of sexual perversion running through her sadism. She sends for Tatiana Romanova (Daniela Bianchi), a young and attractive cipher clerk in the Soviet consulate in Istanbul, to meet with her secretly, certain that nobody outside the Kremlin inner circle knows about her defection.

She compliments the girl on her looks and tells her she's been chosen as the bait to trap a British secret agent; her reward if successful is a promotion, her punishment for refusing the mission death. Lenya hints at Klebb's more personal intentions by letting her hands wander over the pretty blonde; in Ian Fleming's original book she's an avid torturer, and Kronsteen muses to himself that "the tricoteuses of the French Revolution must have had faces like hers."

After telling Romanova that she must "treat me as you would your mother," she concludes their interview by excusing herself and changing into "a semi-transparent nightgown in orange crepe de chine...Underneath could be seen a brassiere consisting of two large pink satin roses. Below, she wore old-fashioned knickers of pink satin with elastic above the knees...Rosa Klebb had taken off her spectacles and her naked face was now thick with mascara and rouge and lipstick."

"She looked like the oldest and ugliest whore in the world," wrote Fleming. Klebb throws herself on a couch with "a squeak of pleasure" and tells the girl to turn off the light before joining her. Romanova slips out the door and flees, concluding one of the many grotesque spectacles that helped make the Bond series massive bestsellers.

It would have read as near-pornographic when it was published in 1957, the fifth in Fleming's Bond series, and famously the one that was listed among President John F. Kennedy's favorite books in LIFE magazine, alongside Winston Churchill's biography of the Duke of Marlborough and Stendahl's The Red and the Black.

It isn't until we've sat through all this prologue that we finally meet Connery's Bond again, dallying in a punt tied up by a riverbank with Sylvia Trench (Eunice Gayson), the posh brunette Bond had pulled over a casino baccarat table at the start of Dr. No. Gayson's Trench was supposed to be Bond's girl in London, a running character throughout the series, but From Russia With Love would be her swansong, not just in the 007 series but on the big screen, though Gayson would continue acting on television, with parts in shows like Danger Man, The Saint, The Avengers and The Dick Emery Show.

The scene marks another goodbye when Bond takes a call from the office on the car phone in his pre-war 3.5 litre Bentley. (Car phones existed but were so rare and expensive that they might have been a Q branch gadget in 1963.) Bond's personal vehicle in three of Fleming's books was a 1930 Blower Bentley, a supercharged model that had won the 24 Hours of Le Mans, and the sort of taste indicator that Fleming liberally used to establish the refined but idiosyncratic side of his spy hero.

At his briefing with Desmond Llewellyn's Q at the start of Goldfinger, the next Bond film, he would be told that the Bentley had "had it's day I'm afraid" before being issued the tricked-out Aston Martin DB5 that's been integral to the Bond legend ever since, returning over and over despite MI6's attempts to replace it with everything from sundry newer Aston Martins to a Lotus Esprit to the product placement BMWs foisted on Bond during the Pierce Brosnan years.

(Llewellyn makes his Bond movie debut in From Russia with Love, as Major Boothroyd of Q Branch and not just plain "Q", the increasingly comic gadgetmaster he would play in seventeen Bond films. One of many Bond film standbys that would see rapid refinement in the Connery years.)

What needs pointing out is what we haven't seen or heard: the show-stopping Bond theme song, the sort of thing that singers would compete to perform with the announcement of each new 007 film, and which would become a permanent part of their concert repertoires for the rest of their careers.

Starting with Goldfinger and Shirley Bassey's performance – the gold standard by which all Bond theme tunes would be measured – the Bond theme has gone from pure bombast (Bassey, Tom Jones' "Thunderball") to wistful (Carly Simon's "Nobody Does it Better") to terrible (Madonna, Sam Smith, A-ha).

It ritually plays over the opening title sequence, which would have its own signature graphic style set by Robert Brownjohn on From Russia with Love and Goldfinger, and then refined forever by Maurice Binder on thirteen Bond films from Thunderball (1965) to License to Kill (1989). It's almost wholly absent at the start of From Russia with Love, though we do hear a snippet of Lionel Bart's theme for the film playing on a transistor radio in another punt as it's pushed past the canoodling Bond and Miss Trench.

We don't hear crooner Matt Monro (unfairly remembered as "the British Sinatra") sing "From Russia with Love" again until the end of the film when, villains vanquished, Bond and Romanova are being rowed in a gondola from the Venice canals to the lagoon on their way back to London, swelling up on the soundtrack as the final credits roll and we're promised that Bond will return.

Monro's contribution to the Bond canon often gets overlooked thanks mostly to unfortunate placement, but I think that's unfair. It's one of my favorite Bond themes, along with Nancy Sinatra's sinuous performance of John Barry's title song for You Only Live Twice (1967) and Soundgarden singer Chris Cornell's suitably bombastic "You Know My Name", the theme to Daniel Craig's debut as Bond in Casino Royale (2006).

In the Bond universe of the second film, Monro's song is on the hit parade, a bit of sonic serendipity that informs the whimsical inscription Bond scribbles on the snapshot from Romanova's MI6 dossier, when he's told by M via office intercom to return the photo to Lois Maxwell's Moneypenny before he heads to Istanbul.

And here's where we need to note another absence in From Russia with Love: production designer Ken Adam, who had created the first Bond villain's ultramodern lair in Dr. No, on a budget exponentially smaller than anything in later films. He had been so successful that Stanley Kubrick hired him to create the War Room set in Dr. Strangelove, so Syd Cain took over design duties, with Adam returning to pioneer high Bond style on every subsequent Bond film from Goldfinger to Moonraker.

It's one reason – among many – why From Russia with Love feels like a standard issue spy thriller, more part of the world of Len Deighton, Graham Greene, Eric Ambler and John le Carré than anything that came after. Instead of dormant volcanos with rocket gantries we have secret tunnels beneath an ancient city, the Hagia Sophia and a vast underground lake (the Cisterna Basilica) built by a Byzantine emperor.

As explained by Bond's liaison in Istanbul, head of Station "T" Ali Kerim Bey (Mexican actor Pedro Armendáriz), the Great Game in the Balkans is an old one, played with different rules, by opponents fully aware that the sides can change at any time and only tribes and family guarantee security.

Armendáriz' Bey is a delightful addition to the 007 dramatis personae and, had he survived to the last reel, it would have marvellous to see him return in future installments as a kind of Felix Leiter of the Levant, but the actor became gravely ill during filming, diagnosed with inoperable cancer. He insisted on finishing his commitment to the production, mostly so he could leave money for his wife, and had to be propped upright during his scenes.

Director Terence Young reorganized the schedule so his scenes could be shot early, and Armendáriz finished dubbing his lines in London before flying back to Mexico with his wife. He checked into the UCLA Medical Center for treatment but took his own life with a gun he'd smuggled into the hospital, while filming continued in Europe.

In Fleming's original novel there was no SPECTRE and no defection of Rosa Klebb from Soviet espionage agency SMERSH, which Fleming helpfully tells us in a note at the beginning of his novel is located "at No. 13 Sretenka Ulitsa, Moscow. The conference room is faithfully described and the intelligence chiefs who meet round the table are real officials who are frequently summoned to that room for purposes similar to those I have recounted."

SPECTRE was probably the cleverest invention Fleming had when it debuted in his 1961 novel Thunderball, and the movies' producers were clever enough to make it central to the Bond universe when they made Dr. No.

In The Man with the Golden Touch: How the BOND Films Conquered the World, Sinclair McKay writes that "when it came to questions of tension on either side of the Iron Curtain, curiously, Broccoli and Fleming were in accord, just at the very point when everyone in the world was assuming the Third World War was an inevitability. At the beginning of 1963, Fleming had this to say to the Jamaican newspaper the Daily Gleaner: 'They (the superpowers) will finally decide to call the game off and we shall be able to settle down and not worry about it any more.'"

While the Cold War had nearly three more decades to run, the Bond films could play out in a parallel universe where both sides of the bipartite conflict were potential victims of a mercenary and wholly evil agency motivated by greed, megalomania and madness and not mere ideology. It let us imagine a common ground, and even made it possible for the 007 franchise to develop a covert audience behind the Iron Curtain, even inside the Kremlin.

(Today, by contrast, more and more people have come to suspect that every government is more SPECTRE than anything else. How will a future Bond and his movies find relevance in this world?)

The LEKTOR – the Soviet decoding machine – is just a MacGuffin, and not the only thing in the film borrowed from Alfred Hitchcock. MI6 and M know that it's a trap, and Kronsteen even assumes that they'll assume it's a trap, but sending 007 into danger on the chance that he might return with the prize just seems like a jolly good show. Bond missions, in the books and future movies, would be built on flimsier, more outlandish premises.

Which brings us to the other prize, Daniela Bianchi's Tatiana Romanova – probably the loveliest of all the Bond Girls, and the most passive. It was still early days in Bond movies; a relatively obscure jobbing actor had been picked to play the hero over a year earlier, and the women of the Bond films were still more likely to be found in the world of beauty pageants than the West End stage.

Bianchi was a former Miss Italy, and she had been roommates at the 1960 Miss Universe competition in Miami Beach with Miss Israel, Aliza Gur. Gur was cast as one of the two gypsy women Bond watches fight each other to the death at the Topkapi encampment (actually shot at Pinewood Studios) where Ali Kerim Bey takes him, assuming it's a safe haven after SPECTRE's Grant provokes a little hot war between Istanbul's Cold War adversaries.

Gur's opponent in the fight was Martine Beswick, a British-Jamaican model and actress who funded a move to London by selling a Mini Cooper she won in a local beauty contest. Or at least that's one of the stories. In documentaries promoting home video releases of the film, Beswick has also said that she was friends with Gur while filming From Russia with Love, while telling another interviewer that "Aliza was a cow... We rehearsed the fight for three weeks but when we shot it, Aliza was really fighting. Everyone encouraged me to fight back, so I did. We got into a real scrapping match."

(In either case Beswick was a favorite of the producers and a rare two-time Bond Girl, returning to play doomed MI6 agent Paula Caplan in Thunderball,)

The gypsy catfight (I'll probably get canceled just for typing those words) is one of those very louche, very unnecessary scenes that sets Fleming apart from more sober-sided spy story writers. Fleming's language describing the violence is palpably erotic and charged with sadism:

"Bond saw that Vida's head was buried deep in the other's breasts. Her teeth were at work...Bond held his breath at the sight of the two glistening, naked bodies, and he could feel Kerim's body tense beside him. The ring of gypsies seemed to have come closer to the two fighters. The moon shone on glittering eyes and there was the whisper of hot, panting breath."

Young could not, of course, show anything this explicit in his movie but he goes as far as censors would allow, and in any case the fight is interrupted when a gang of Bulgarians attack the gypsy camp, which sets off a battle with knives and fire and gunplay that Connery's Bond negotiates with boyish grace, unaware that Shaw's Grant is watching out for him the whole time, shooting down a Bulgar about to plunge a blade into Bond's back.

The rest of the film is the usual marvellous 007 nonsense, with the killing of the Bulgarian ringleader (caught emerging from his bolthole through a trap door in Anita Ekberg's mouth on a billboard advertising Call Me Bwana, the last Broccoli/Saltzman production), a bomb under the Soviet consulate to snag the LEKTOR and an escape aboard the Orient Express from Sirkeci railway station.

This is where the first great one-on-one fight in the Bond films takes place, after Grant boards the train in the guise of an MI6 operative tasked with helping Bond and Tatiana escape by sea through Trieste to Venice. Grant – a psychopath escapee from Dartmoor before recruitment by SPECTRE – gives himself away to Bond by ordering Chianti with his fish in the dining car, and after Bond tricks him into opening one of the booby-trapped suitcases issued by Q Branch, the two men battle it out in the tear gas-filled sleeping compartment.

This was the first Bond fight scene where the audience is really supposed to feel it, and it wouldn't be equalled again until Daniel Craig's first 007 pictures. Connery and Shaw seem equally matched though my money would have been on Shaw if this wasn't a movie. Young had been a boxer in college and took three weeks to film the scene at Pinewood, with Connery and Shaw only using stuntmen for a few shots. McKay is suitably impressed in his book:

"It's the implacable violet of the compartment night-light that somehow sticks in the mind, the only point of stability in a breathtaking blur of fists, punches, swings, kicks, all choreographed in this claustrophobically small space. Praise has justly gone to the film's editor, Peter Hunt; with his lightning-fast cuts, not all of them matching perfectly (some left-handers become right-handers), he rewrote the grammar of screen action. It is a violent, pacy impressionist blur as opposed to the more traditional medium shot of two actors taking fake swings at each other."

After this it's to be expected that two subsequent action sequences – a helicopter full of SPECTRE baddies swooping down on Bond as he runs across treeless hills (a blatant copy of similar scenes from Hitchcock's The 39 Steps and North by Northwest) and a boat chase on the home stretch toward Venice – play rather flabbily onscreen. "That's another thing that Bond producers never really learn," McKay writes: "Boat chases are intrinsically dull."

Thankfully there's a brief final bit of action when Klebb, disguised as a maid, tries to retrieve the LEKTOR and Tatiana from their Venice hotel room, kicking at Bond with the poisoned blade in the toe of her shoe while he pins her against the wall with a chair. Dispatched by Tatiana with Bond's gun, Lenya sells Klebb's death with all the dramatic skill and unexpected pathos you'd expect from a legend.

After that it's Connery and Bianchi, the gondola on the lagoon and the off-camera snog while Matt Monro and Bart's theme song swells on the soundtrack. I remember watching the film as a boy and wondering why Monro's melancholy but ominous ballad (arranged by John Barry and produced by no less than George Martin) made me so sad. It's taken years to understand that it was because this was the last moment when 007 movies were truly fresh, before box office and budgets skyrocketed and ritual overtook inspiration in their creation.

"To look back now," McKay writes, "you can see that From Russia with Love was actually the last Bond movie of its type. It was the last to play a gadget-filled briefcase absolutely straight. It was the last to make Bond the centre of an essentially small-scale spy-versus-spy melodrama. It was the last (for a while) in which Bond's attentions would be focused on just one woman."

James Bond is dead, for now. And while his resurrection is imminent, neither he nor his films will ever be free to find their form again while the world demands that 007 ticks as many boxes as social utility demands. We will get the Bond that disinterested parties presume we need and not the Bond that his fans want; that man died from relentless second-guessing long before those Royal Navy missiles hit him.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.