Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon wasn't a big hit when it was released in Japan, but when it won a Golden Lion at the 1951 Venice Film Festival it opened the floodgates for Japanese cinema into the cinemas and film festivals of the west. No less than Ed Sullivan wrote that "the direction, the photography and the performances will jar open your eyes," and within a year films by Mizoguchi and Ozu joined Fellini, Bergman and Rossellini in the art houses.

It took barely ten years from Hiroshima and Nagasaki and VJ Day for Japan to go from vicious, possibly subhuman enemy to a culture worth studying and admiring. This shouldn't be surprising; Japan was already in the habit of rapidly transforming both itself and its relationship with the world, and with a massive US military presence occupying Japan until well after the end of the Korean War, the wives and families of servicemen stationed in the country turned out to be its first, best ambassadors.

"Military wives taught their American friends about the arts and traditions they encountered living in Japan," wrote Meghan Warner Mettler in her book How to Reach Japan by Subway: America's Fascination with Japanese Culture, 1945-1965, "while homemakers did their part as consumers to purchase and display Japan-inspired furnishings."

A new wave of Japonisme broke out in the west half a century after the first one; flower arranging and ceramics and Japan's elegant and austere art harmonized well with mid-century modernism, and haiku poetry and Zen Buddhism would take their place on the bookshelves of intellectuals, pseudo- and otherwise.

(Think of Robert Morse's Bertram Cooper in the series Mad Men, asking executives to take off their shoes when entering his tastefully decorated office with its framed Japanese woodcut prints on the walls.)

But a less obviously refined part of Japanese culture was exported along with the tea sets, calligraphy scrolls and cameras – the samurai film, which Kurosawa brought to the west with the release of Seven Samurai (1954). They appealed to men, as Mettler writes: "Samurai movies and Zen Buddhism both included undeniably 'manly' elements like swordplay and tough-minded stoicism. Because associating such traits with Japan could disrupt the image of the nation as peace-loving and eager to accept U.S. aid, such masculine attributes often lost their menace when they appeared as safely contained in Japan's distant past."

Which is how Kihachi Okamoto's The Sword of Doom (1966) begins, with a caption over the first shot telling us that it's the spring of 1860. An old man and his granddaughter reach a shrine at the top of a mountain trail; he's a pilgrim and explains that a saint had once visited the spot, burying an image of the Buddha which purified the waters of the rivers flowing on either side of the mountain. He asks her to go fetch water, and kneels before the shrine, praying for death to release him and, more importantly, to free his granddaughter to begin her life free of her obligation to him.

He gets an answer, in the form of Ryunosuke Tsukue (Tatsuya Nakadai), a lone samurai wearing a wide conical straw hat, who grimly offers to grant his wish – and does so, drawing his sword and cutting the old man down in cold blood. Without any apparent remorse he sets off down the path, passing an itinerant salesman (Ko Nishimura) and idly swiping at him with his blade, and then the pilgrim's granddaughter, who discovers the old man's body along with the peddler and collapses, wailing with grief.

Ryunosuke is a samurai of rare and terrifying talent, the son of a dying master swordsman who is dismayed at his son's lack of morals or honour. He tells him that he has been challenged to a duel with Bunnojo (Ichiro Nakaya), a samurai from a rival school, and is commanded to lose the match so that Bunnojo can win a position at the court of a great nobleman and with it the means to support his family.

But before the match Ryunosuke is visited by Bunnojo's wife Ohama (Michiyo Aratama), who pleads with him to let her husband win. The samurai tells her to meet him at a water mill on his father's property, where he seals the bargain by raping her. Unfortunately Bunnojo finds out, divorces her on the morning of the contest, and makes the mistake of losing his composure and lunging at Ryunosuke, who easily dodges his attack and kills Bunnojo with a single blow of his wooden sword.

Okamoto uses the match to introduce us to Ryunosuke's strange, devastating style, which is key to understanding the psychology of the film's protagonist – definitely no hero, even less an antihero, but basically a full-blown psychopath. As the two men face each other, they move like statues, the camera following their feet as they sweep slowly behind and around them, their bokken held at rigid angles.

It's a beautiful example of the great stillness and tension that Japanese filmmakers refined and brought to world cinema, an echo of the lethal pauses that were crucial to gunfighter's duels in westerns, which would bounce back into the genre with the spaghetti westerns of directors like Sergio Leone.

As his opponent tenses himself for the inevitable attack, we see the tip of Ryunosuke's sword slowly drop to the ground, while the samurai's expression become distant and listless, even catatonic. Fooled into thinking he has an opening, Bunnojo lunges in a rage, right into the trap set by Ryunosuke.

Fleeing town after the match Ryunosuke is warned by Ohama that her husband's clansmen are waiting to ambush him; they surround him on all sides on a foggy path through the forest, but he cuts through them in the first of the film's set piece sword battles, inviting attacks with every listless lapse, leaving a trail of bodies behind him.

The Sword of Doom was an adaptation of Great Bodhisattva Pass (or The Pass of the Great Buddha), a novel by Kaizan Nakazato that was based on a newspaper serial that ran for over three decades starting in 1913. (Its Japanese title, Dai-bosatsu Toge, is the original title of Okamoto's film.) It had been adapted several times, in a two-part film in 1935, over three parts in 1953, again in a trilogy released between 1957 and 1959 and in another three-part version released in 1960 and 1961. Okamoto was assigned to direct his heavily edited version of the story as a punishment by his studio, Toho, when they were disappointed by his film The Age of Assassins, which they didn't release until 1967.

The time frame of Okamoto's film is almost exactly that of the U.S. Civil War, which began seven years after Commodore Perry's Black Ships steamed into the harbour at Edo and forced Japan to end over two centuries of isolation and begin trading with the world, an audacious example of gunboat diplomacy.

The period between Perry's ultimatum and the restoration of the Meiji emperor to power in 1867 marked the agonizing collapse of the Tokugawa shogunate, which had kept Japan frozen in a feudal state. This essentially medieval country without wheels or engines is the setting of Nakazato's story, a time when economic stagnation and hypertrophied bureaucracy filled the country with rogue samurai and masterless ronin – mercenaries like Ryunosuke who has been expelled from the swordsmen's schools that provided what few places were available for dangerous men like him.

In his book The Samura Film, Alain Silver compares this period to the United in the last half of the 19th century, which would become the setting of the western movie – the genre which the samurai picture resembles most, where "the feudal daimyo and their clansmen tried unsuccessfully – like the anachronistic 'cattle barons' – to keep the Japanese equivalent of the homesteader at bay with the threat of violent death."

"Like the bounty hunter or hired gun, the swordsman, whether a true samurai or wandering mercenary, may align himself with either of these factions; he may be either good or evil or a figure of moral ambivalence depending more on individual characteristics than genre typing, because like the Western's scruples against never drawing first or back-shooting, bushido is not always unswervingly adhered to by either hero or villain."

It's a violent and nightmarish world that provides the setting for Japanese jidaigeki dramas, a world on the brink of civil war and unprecedented change that still resembles the medieval country that had last been seen by Portuguese traders before they were expelled from Japan when the Sakoku laws were enacted in 1635. It's a place where even outcast samurai can still kill anyone beneath them in the country's harsh caste system on mere suspicion of challenging their honour, which is why Ryunosuke can murder an old pilgrim on a whim without fear of retribution.

The only threat to samurai like Ryunosuke is vengeance as demanded by the samurai code of bushido, and so when we see him two years later his only concern is Hyoma (Yuzo Kayama), the younger brother of Bunnojo, who is now the assistant to Shimada (Toshiro Mifune), the master of a swordsman's school.

The young man was sworn by Ryunosuke's dying father to kill his son for becoming a monster, absorbed by the evil side of the swordsman's art. (The dark side of the force, if you will.) Hyoma is also besotted with Omatsu (Yoko Naito), the granddaughter of the pilgrim Ryunosuke murdered in the first scene, now apprenticed to the owner of a flower arranging school – a position arranged for her by Shichibei, the traveling peddler from the first scene, who is posing as her uncle.

Ryunosuke is now unhappily married to Ohama, with whom he has an infant son, and has found employment in a group of ronin who carry out assassinations to protect the power of the waning shogunate from growing political change. Politics by assassination is an evergreen feature of Japanese politics; it helped maintain the power of the military in the decades before Pearl Harbor.

It persisted in the turmoil of postwar democratization, most famously in 1960 when a 17-year-old student stabbed to death Inejiro Asanuma, chairman of Japan's socialist party, on stage during a televised debate. It continues to this day: former president Shinzo Abe was murdered in public just two years ago by a man wielding a homemade shotgun.

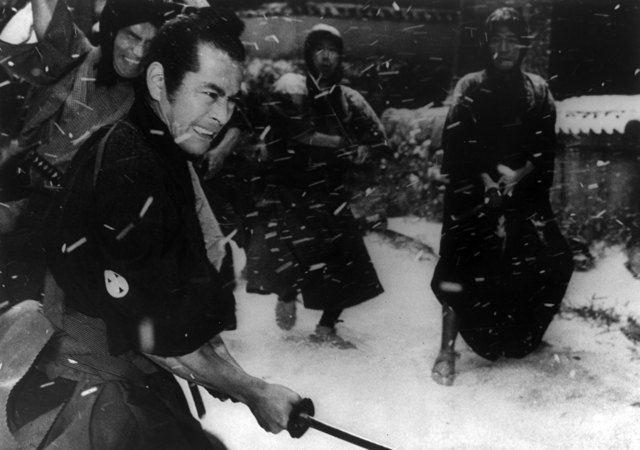

Ryunosuke and the rogue ronin plan to ambush an aristocrat who is traveling in one of two palanquins but they pick the wrong one, and discover that it carries Shimada, who stands alone against the band of killers in the snowy night. But like Ryunosuke earlier in the picture, he's the superior swordsman, massacring them with spectacular skill while Ryunosuke watches in awe and horror.

Mifune basically plays the role of the final boss in a video game, declaring that "The sword is the soul. Study the soul to know the sword. Evil mind, evil sword." Ryunosuke is unnerved by watching the older man display skills that outshine his own, and returns to Ohama and their home to numb his fear with alcohol but gets told that they're out of sake.

The couple fling recriminations at each other. Ohama wishes she were still with Bunnojo and not the wife of an outcast; Ryunosuke blames her, saying that she's an evil woman. She tries to kill him in his sleep but fails; pursued around the snow-covered garden, she asks him if he wants to "kill everyone in the world." His response is to calmly kill her with a single thrust of his katana, and he walks away while their infant son cries.

Time passes again and Ryunosuke is a member of another gang of ronin assassins, a larger group this time with a simmering power struggle over who should lead them. But what unifies them all is the unease with which they view Ryunosuke, who holds himself aloof, envied and resented for his pitiless skill with a sword.

The film's subplots seem to converge on the homicidal samurai; Hyoma has been honing his skills on Shimada's orders, perfecting the single lunge that could possibly defeat Ryunosuke's "silent form" or "evil sword". Shichibei, it turns out, is more than a mere peddler, as he trades in pistols and other western weapons for a select clientele. He's also something of a ninja, sneaking into the home of the flower arranging teacher and threatening her to confess that she sold Omatsu into service as a courtesan in an oiran – a high class brothel.

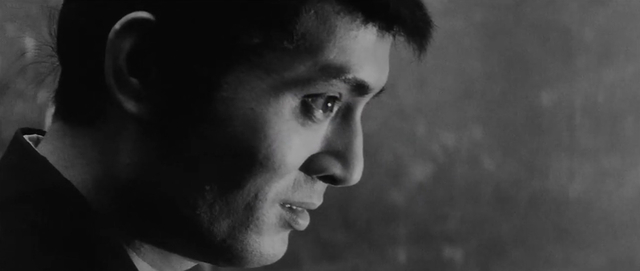

The Sword of Doom is a disturbing story, and succeeds because of Okamoto's stark vision and the performance of Tatsuya Nakadai as Ryunosuke. Far less famous outside Japan than Mifune, he began his career with a walk-on part in Seven Samurai, before going on to larger roles in Kurosawa's Yojimbo, Sanjuro and High and Low. He made several films with Masaki Kobayashi, including Harakiri (1962) and the brilliant horror anthology Kwaidan (1964). Nakadai would play the protagonist (and his double) in Kurosawa's late career masterpiece Kagemusha (1980) and as the tragic aging warlord in Ran (1985), the director's adaptation of King Lear.

Okamoto's camera frequently zooms in on Nakadai as Ryunosuke, and on his eyes under the wide straw hats he favours. They're usually glassy and withdrawn, emitting no sign of an interior life, like a sleepless predator. Usually expressionless, his mouth will twist into a grin when either contemplating violence or pausing briefly mid-slaughter.

Samurai films trade in stylized violence; their bloody sword battles, with outnumbered heroes dispatching their adversaries with great gouts and geysers of blood spraying across shoji screes, are one of the genres gifts to the modern action movie. But the violence in Okamoto's film is particularly extreme for the time and might have seemed even more terrible if he hadn't chosen to film in black and white.

His set piece sword battles in The Sword of Doom are among the best in the whole genre, which Alain Silver sums up as "unnervingly orchestrated sound effects of steel ripping into flesh and images of spurting blood which stains clothing or ... leaves dark, red blotches in freshly fallen snow" and where "a new type of samurai is defined: pitiless, obsessive, perhaps more alienated than any other genre hero."

Hyoma and Shichibei prepare for the young samurai to get his revenge at the oiran where Omatsu is working, but Okamoto chooses to blithely drop the thread of Hyoma confronting his brother's killer altogether at the film's conclusion. Their subplot represents order trying to reassert itself – and few societies value order as much as Japan – but the film spirals into chaos whenever the camera gets close to Ryunosuke, as the violence he seeks and creates becomes orgiastic and hallucinatory, a black hole that we're pulled into.

While the other ronin turn on each other Ryunosuke is left alone with Omatsu and discovers her connection to the old pilgrim he murdered at the start of the film. This seems to push him over finally into madness; he begins slashing at the woven screen walls all around him as the spectres of the old man, of Ohama and Shimada, taunt him in the shadows.

The spectres turn into his fellow gang members, tasked with killing him, and Silver writes that for Ryunosuke "killing becomes such a necessary function that after his real adversaries are exhausted his mind creates phantoms to oppose him in an unending battle." Wounded but unable to stop fighting, he constantly revives himself to take on the apparently endless army of men, and Okamoto ends his film with a freeze frame of Nakadai's samurai slashing at the camera one last time.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.