Unique among great American cities, corruption is baked into the foundational lore of Chicago. It's a truth that every generation gets to rediscover at intervals spaced far enough apart as to make this revelation more demoralizing than it should be. It's true today, and it was true in a 1938 film set in 1871, about the most important historical event in the city's history that didn't involve a councilman, mayor or governor going to jail.

"From the moment of its incorporation as a city in 1837," wrote Ovid Demaris in his 1969 book Captive City: The Startling Truth about Chicago and the Mafia, "Chicago has been systematically seduced, looted, and pilloried by an aeonian horde of venal politicians, mercenary businessmen, and sadistic gangsters. Nothing has changed in more than 130 years."

Chicago doesn't have a monopoly on corruption. New York City has Tammany Hall, Boss Tweed, Jimmy Walker and nearly two centuries of machine politics. Cities as different as St. Louis, Los Angeles, Newark, Kansas City, Memphis, Miami and New Orleans can't retell their histories without listing – even celebrating – the rapacious party bosses and bent politicians whose legacy is written all over their streets. Uber drivers in Atlantic City will (as I learned firsthand) cheerfully give you a rundown of their past and present political rot while pointing out landmarks and great places to eat.

In Old Chicago begins, as the titles tell us, in 1854 on the midwestern prairie where the O'Leary family are traveling by covered wagon westward to the burgeoning city near the bottom of Lake Michigan, a place that patriarch Patrick calls the "hub of the country". Alas poor Patrick falls victim to Irish movie stereotypes and lets his reckless and impulsive nature – goaded on by one of his sons – convince him to race a steam train.

He loses control of the wagon and gets dragged across the prairie still holding the reins of the horses when they break free. Dying, he tells his sons to make their fortunes in the big city just over the horizon and asks his wife Molly (Alice Brady) to bury him there and let Chicago come to him as it grows. (We presume that he joins the voter rolls of Cook County in perpetuity as he expires.)

When they arrive, starving and exhausted, they find the streets are potholed and thick with mud, which provides an opportunity for Molly to set up a laundry service to wash the filth from the clothes of the fine ladies of the city (starting with a carriage of what we're meant to understand through the gauzy blur of the Production Code are high priced prostitutes and their madam).

Time passes in a montage of years inscribed on soap bubbles, surging forward to 1867. Molly's laundry business and her boys have grown. The youngest, Bob (Tom Brown), is a hard worker and a good boy, in love with the O'Leary's German servant girl Gretchen (June Storey). He's also the least interesting of the three, and the story doesn't linger on him unnecessarily.

Jack (Don Ameche) is a young lawyer, a crusader for reform causes with ambitions to eradicate the corruption that already permeates Chicago's political culture. His brother Dion (Tyrone Power) is a rogue – a gambler who moves in the retinue of Gil Warren (Brian Donlevy), one of the city's bosses and proprietor of a network of ward heelers, bribed politicians and police officials.

Ma O'Leary discovers a map scrawled on a tablecloth from Warren's saloon, The Hub, and her boys note that it's a map showing a street railway line going down a different route from the one stipulated in a recent bond issue. It turns out Warren is pulling a bait-and-switch, rerouting the streetcar past a plot of land owned by Belle Fawcett (Alice Faye), the star performer at his saloon. Jack is outraged, but Dion sees opportunity.

He sets his sights on Belle, essentially stalking and forcing himself on her in her own bedroom. (No joke; it's hard to believe that audiences in 1938 took this in their stride, but we're meant to assume they did.) He and Belle end up as both business and romantic partners, opening their own high-class saloon, The Senate, which is so popular that Warren makes Dion an offer: he'll shut down The Hub and eliminate the competition if Dion supports his bid for mayor and delivers votes from "The Patch," the crowded, run-down working-class neighbourhood where his mother runs her laundry.

There's still a neighbourhood known as The Patch in Chicago's west side, also called Smith Park. This is, however, far from the site of the barn on W. DeKoven St. by the South branch of the Chicago River owned by Mrs. O'Leary, whose cow was popularly blamed for setting the blaze that would start the Great Chicago Fire in 1871. The film's credits thank the Chicago Historical Society for assistance in research, but In Old Chicago diverges considerably from the historical facts, very notably when it deals with the O'Leary family.

The O'Leary brothers are set up as a midwestern Cain and Abel, though it would be more interesting had the roles been reversed. It might have been a more successful casting, as Ameche was capable of more depth than Power as lovable rogues, like the regretful philanderer in Ernst Lubitsch's Heaven Can Wait. Power seems altogether too pleased with himself when Dion pulls sly, self-serving double crosses on Warren and then his brother; so much that it makes his later redemption less plausible.

Alice Faye's career began as a vaudeville chorus girl and she got her break when Lilian Harvey dropped out of George White's Scandals (1934). She became a protégé of Darryl F. Zanuck at Fox, who shifted her image from wisecracking to wholesome. The role of Belle was written for Jean Harlow, but Faye got the part after Harlow's sudden death.

Her slightly husky voice made her a favorite of Irving Berlin, George Gershwin and Cole Porter, and she was at her box office peak when she made In Old Chicago, described as the female equivalent of crooner Bing Crosby. She wasn't really much of a dancer going by her musical numbers on the saloon stages in the film, but that might be blamed on the rather slapdash choreography of Fox musicals – far from what you'd expect from musicals produced by RKO, Warners and especially MGM at the time.

Jack agrees to run against Warren as the reform candidate when he's approached by a group of upright businessmen and citizens; a scene later we learn that they were sent by Dion, who knew his brother would take the bait. While seeming to publicly support Warren, Dion bribes the police commissioner and stage manages a brawl at Warren's premature victory party that gets Warren's ward-heelers and henchmen thrown in jail, unable to deliver votes for their candidate.

Dion's logic was that his brother would be a mayor more controllable than Warren; he tells his brother that "People don't trust an honest man in office." When Jack discovers his treachery he promises to make prosecuting Dion his number two priority – after cleaning out The Patch as the start of a campaign to rid Chicago of corruption. When Belle agrees to testify against Dion, he professes his regret and begs her to marry him, going so far as to ask his brother to officiate.

Power's smug look of triumph after their vows when he reminds both Jack and Belle that a wife can't testify against her husband in court is too much for his brother. Belle flees her wedding and the two men commence a knock-down drag-out fight in the mayor's office that ends with Dion on the carpet.

At this point the film shows us how the feud between the brothers led to the destruction of their city. Back home Ma O'Leary is helping her cow Daisy nurse a new calf, but rushes away when she hears about their fight, leaving a lit oil lantern that the skittish bovine knocks over, starting the catastrophic disaster.

This would all be news to Roswell B. Mason, the former railway engineer who was mayor of Chicago when the 1871 fire started, though he really was elected on a reform ticket – the last major of the city who wasn't a member of either major political party. (Before winning office he was one of the engineers who worked on the project that reversed the direction of the Chicago River.)

And the real name of Mrs. O'Leary wasn't Molly but Catherine; her husband's name was Patrick but he was still alive when the fire started, and they did have three children. One of them, Jim, would become a saloonkeeper by the Stockyards with connections to Chicago's political establishment, though he was only two at the time of the fire. And the real Mrs. O'Leary ran a dairy, not a laundry.

We see Jack in the bell tower of the city courthouse where firewatchers had spotted the start of the blaze (though they got its location wrong, and firefighters didn't arrive on DeKoven Street until the fire was well out of control). In the tower with him is Gen. Philip Sheridan (Sidney Blackmere), the Civil War hero who was really in Chicago when the fire started, and just as in real life he suggests containing the blaze by demolishing buildings to create a firebreak.

The old courthouse was one of the hundreds of buildings lost to the fire; witnesses recall its great bell falling to the ground with a clang that was heard for miles. But the amazing thing is that conflagrations like the Great Chicago Fire were regular disasters in cities throughout the 19th and into the early 20th century.

Thanks to wooden construction, tarred roofs, primitive infrastructure and fire departments that were too understaffed and poorly equipped to deal with fires that quickly consumed block after block, the downtowns of cities like New York, Charleston, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Albany, Toronto, San Francisco, Montreal, Portland, Quebec City, Boston, Calgary, Vancouver, Seattle, Spokane, El Paso, Jacksonville, Baltimore, Atlanta and Houston would have at least one disastrous fire before the end of World War One. In 1871 alone fires would destroy not just Chicago but nearby towns in Illinois and Michigan.

Until the last third of the picture you might have assumed that In Old Chicago was a bit of a musical and a bit of a drama with liberal comic touches. But as soon as Daisy kicks over the lantern we're reminded that the film is known primarily as a disaster film, made in the shadow of MGM's San Francisco (1936).

Director Henry King was the epitome of a journeyman, but he delivers the horror and terror of the disaster magnificently; the blaze roars across the quickly built, pine-framed shanties into the downtown, where it settles onto the tar roofs of buildings made of brick and stone. The heat from the actual fire was so intense that limestone cladding on banks and offices seemed to melt into the street, and King fills the screen with flames, smoke and noise.

One of his finest touches is the din produced by the steam whistles on the coal boilers used to pump water by firefighters. They create a cacophony all over the blazing city that would have been remembered by anyone in the audience old enough to remember horsedrawn fire engines.

The characters are scattered across the panicked streets between the fires as crowds desperately head for the river and, once the fire breaches that, the lake. The brothers are reunited just as an angry mob led by Warren finds them, stoked with the idea that the fire was set by Jack and Dion to speed up the clearance of The Patch. The mob tries to pull down the fuses set by Sheridan's soldiers to demolish buildings for the firebreak, and Warren's henchman mortally wounds Jack with his pistol before the blast collapses a building façade down on the mayor.

(Rondo Hatton plays Rondo, the henchman. His face disfigured by acromegaly, Hatton was a veteran of WW1 trenches and the Pancho Villa Expedition who was cast by Henry King while he was covering the filming of Hell Harbor (1930) for the Tampa Tribune. He would appear in small but very visible roles in films like King's Alexander's Ragtime Band, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (as "Ugly Man"), The Ox-Bow Incident and as "The Hoxton Creeper" in the Sherlock Holmes picture The Pearl of Death. He'd reprise the monstrous "Creeper" again in Universal's House of Horrors and The Brute Man before his death in 1946.)

Chicago would rebuild, becoming one of the architectural showcases of the United States, but Mrs. O'Leary would find no joy in her hometown's revival. There's no way of knowing if the fire was set by her dairy cow but Michael Ahern, a reporter for the Chicago Republican, admitted later that he had made up the story with two other newspapermen, and the tale caught on as quickly as the fire, particularly in William Bross' virulently anti-Irish Chicago Tribune.

Despite being cleared by an inquiry, Mrs. O'Leary became a popular scapegoat for the disaster, and was hounded by reporters for the rest of her life. Reenactors portraying Mrs. O'Leary and her cow would be regular features in Chicago parades for decades. One lyrical variation of the 1896 popular song "A Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight" features the verse:

Late last night when we were all in bed,

Mrs. O'Leary left her lantern in the shed.

Well, the cow kicked it over, and this is what they said:

There'll be a hot time in the old town tonight!

And while In Old Chicago played a big part in keeping the O'Leary legend alive, a website devoted to the abiding myth of the Irishwoman and her cow notes that in King's film "Hollywood turned once-despised immigrants like the O'Learys into upwardly mobile champions of the Chicago booster dream."

Standing in the water looking back over the smoking ruins of the fire that has taken her home and her son's life, Molly O'Leary tells her surviving family that they'll rebuild as a tribute to Jack, and that "Nothing can lick Chicago."

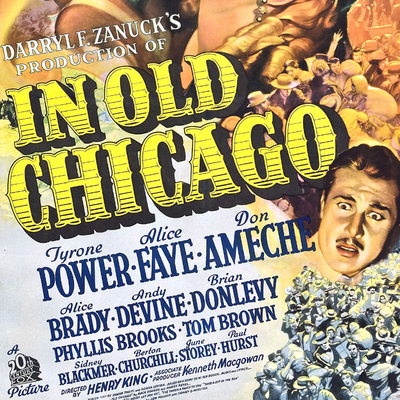

In Old Chicago was nominated for six Academy Awards including Best Picture, and Alice Brady won Best Actress in a Supporting Role for her Ma O'Leary. The real Mrs. O'Leary would finally get an official proclamation of her innocence from the City of Chicago in 1997.

In real life men like Bross who ran Chicago saw an opportunity in the chaos after the fire. With thousands deprived of homes, they offered one-way railway tickets to unfortunate victims willing to move on and relocate, hoping to reduce the city's population of poor Irish Catholics and African Americans.

Nothing could, indeed, lick Chicago, and the Tribune's Bross immediately went to New York to solicit investors in the rebuilding and entice ambitious young men to head to the disaster zone as "never again will you have this chance to make money."

All the new money and improved building standards, not to mention the roster of star architects who'd pioneer the skyscraper there would make the future city safe for a gallery of political grotesques like William Hale Thompson, Michael "Hinky Dink" Kenna, "Bathhouse" John Coughlin, Len Small, Richard J. Daley, Rahm Emmanuel, Richard M. Daley, George Ryan, Rod Blagojevich, Thomas Cullerton, Luis Arroyo, Lori Lightfoot and many, many others.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.