Even if you love the genre, it's hard to say whether the world of the screwball comedy is a kind of paradise or simply a circle of hell. It is, to be sure, its own world – a parallel universe where stereotypes exist to be mocked, inhibitions are quickly overcome, and the usual laws of action and reaction take a circuitous, often improbable route.

The fact is that screwball started in the wake of the Production Code, when there were things that could no longer be shown, so they were talked about instead, by the kinds of people who knew what they were talking about (newspaper reporters, dissipated heirs and heiresses, louche society hangers-on, bums with a colourful past).

But they happened in a world where anything was possible (a leopard is kept as a pet; a rich careless couple return from the dead to haunt their banker; an unhappy millionaire invites a jobless young woman to live in his mansion) and the only question is how well the heroine – usually the most vital character in the story – and the hero can roll with the ensuing chaos.

Nothing Sacred (1937) begins – as most screwballs do – in Manhattan where the Morning Star, a major newspaper, is holding a banquet to celebrate the pink-turbaned "Sultan of Maw-Zoo-Pan" as he is introduced by the paper's editor, Oliver Stone (Walter Connolly). The Sultan (Troy Brown) is about to bestow a vast new palace of culture on the city – "Twenty-seven halls of learning! Twenty-seven arenas of art!" – when his wife (Hattie McDaniel) interrupts his solemn benediction, dragging with her their four children and two policemen.

The Sultan, it turns out, was a bootblack and petty fraudster who had been promoted in the pages of the Star by its star reporter Wally Cook (Frederic March), who we had spied looking worse for wear on the podium at the banquet. Whether he'd tied one on after learning of the Sultan's true identity or had been on a bender long enough to innocently facilitate the con isn't known; what we do know is that Stone sentences Cook to spend the rest of his contract entombed in the obituary page.

It would be a short film if March's Cook isn't able to escape his punishment, so he marches into his boss' office and pitches one last story – the tale of Hazel Flagg (Carole Lombard), an unfortunate small-town girl dying of radium poisoning, whose tragedy had been buried in a few column inches in the paper. It's the kind of human-interest story that readers can't resist, and all Cook has to do is find the girl and bring her to New York City from her hometown of Warsaw, Vermont.

Hazel's hometown is a cityfolk nightmare of a small Yankee town, with wooden sidewalks, monosyllabic locals and feral children. (A toddler darts out from behind a white picket fence to bite March on the leg.) Inquiries about Hazel are met with terse disavowals, for which the townsfolk have the audacity to request payment. "I forgot I was in Vermont," March drily remarks as he reaches into his pocket. (Look for Margaret Hamilton as the fierce biddy running the drug store.)

But when Hazel visits Downer the town doctor (Charles Winninger) the bibulous sawbones admits that he'd botched his diagnosis of radium poisoning. ("I got so I was seeing radium poisoning everywhere!" he pleads.) Which is kind of a shame as Hazel has already taken the $200 the watch factory that runs the town gifts every local who dies there.

Hazel never had any intention of dying in Warsaw, so she's primed for Cook's sales pitch when he corners her outside the doctor's office, offering her gratis the trip she was planning on taking to New York City as her last fling before dying. She neglects to let him know about her reprieve, and for good measure takes Downer along with her to New York in the Star's private plane.

Nothing Sacred was based on a short story in Cosmopolitan magazine, adapted by none other than Ben Hecht, with uncredited contributions to the script by (get this) Budd Schulberg, Ring Lardner Jr., Dorothy Parker, Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman among others. But it has Hecht's caustic worldview all over it, from the purgatorial small town to the big city full of frauds, knowing and unknowing.

Director William Wellman was probably at the peak of his career; he had begun the year with the release of A Star is Born and would follow up Nothing Sacred with Men With Wings (1938) and Beau Geste (1939), the sorts of action and adventure films that he generally preferred. Wellman was no Gregory La Cava, Wesley Ruggles or Mitchell Leisen – he isn't famous as a screwball director, but it's indicative of his legendary stature that his rare foray into the genre is one of its highlights.

It helped that his leading lady was Carole Lombard, who had been there at the birth of the screwball genre with films like No Man of Her Own (1932, with Ruggles), which begins much like Nothing Sacred with a spirited young woman wasting away in a small town being rescued by a morally compromised city slicker (Clark Gable in the earlier film).

She would go on make her mark on screwball in We're Not Dressing, Twentieth Century, The Gay Bride (all three in 1934), Hands Across the Table (1935, with Leisen), Love Before Breakfast, The Princess Comes Across and finally the genre classic My Man Godfrey (all three in 1936, the last with La Cava). She began 1937 with Swing High, Swing Low (Leisen again) and only had a weekend off between filming True Confession with Ruggles and starting on Nothing Sacred; both films would be released nationally on the same day.

(As a sidenote, Janet Gaynor was apparently originally cast as Hazel, before Welman met Lombard and insisted producer David Selznick hire her. I find it almost impossible to imagine the film with Gaynor.)

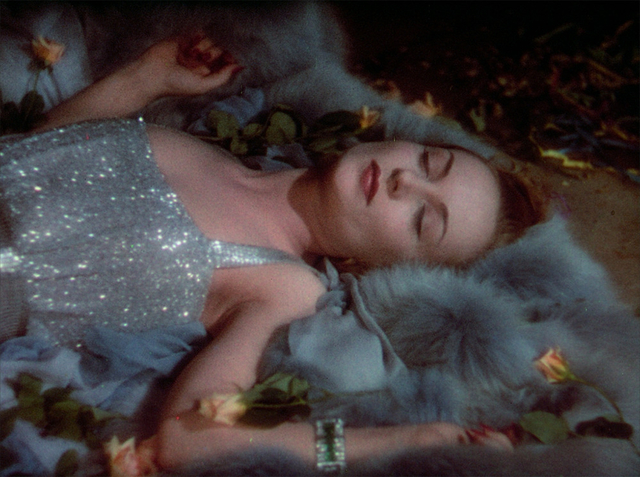

Nothing Sacred is one of the few screwballs to be shot in three-strip Technicolor – a film medium still struggling for acceptance by the studios. (Disney had so far been the only one to go all in on the cumbersome process.) The results are still quite tentative, more subtle and jewel-like than the vivid primaries Technicolor would deliver on The Wizard of Oz two years later.

As James Harvey writes in Romantic Comedy in Hollywood from Lubitsch to Sturges, "Hazel Flagg's New York is heartless, hypocritical, corrupt. But it looks – in the delicate and ravishing pastels of early Technicolor – like Oz, unreal, rainbow-hued, magical. From the sky as Hazel's plane flies in from Vermont, from the Hudson River as she and Wally go sailing there, it's an enchanted place. Even its interiors, the arenas and nightclubs and banquet halls, suggest space and freedom, flight and elation."

It helps that the film's soundtrack is by Oscar Levant, who furnishes appropriately Gershwinesque music. Additionally the band in the nightclub scene – with its hilariously overdone stage show celebrating "women of history" like Catherine the Great and Lady Godiva on horseback as a tribute to Hazel ("Mother Earth Salutes Hazel Flagg") – is none other than Raymond Scott's; an innovator both musically and technically, he would be the major inspiration for Carl Stalling and his whiplash scores for Looney Tunes. Stalling would use Scott's tunes and themes, like the instantly recognizable "Powerhouse", all over the classic cartoons.

What's obvious from the start is that Hazel is being used, even as the Star gets her feted from the moment she arrives in Manhattan, with ticker tape parades and the key to the city from the mayor. (Unsure what to do with the ridiculous prop, Lombard tries to put it down the front of her dress.) She ends up in great seats at a wrestling match at Madison Square Garden – attendance at these bouts and prize fights in full evening dress was apparently a celebrity ritual back in the '30s – listening guiltily as Wally comments sourly on the fakeness of the spectacle.

The barbed gag of Nothing Sacred, of course, is that Hazel is using everyone right back. Her conscience is occasionally troubled, but it doesn't bother her as much as how her mere presence – even the mention of her name – can reduce everyone around her to baleful stares and weeping. The city slickers, like Wally, pity her while assuming they're privy to insights she can't possibly understand, and when their tone with Hazel isn't condescending it's smarmy.

"She is always coming up against language like this," writes Harvey. "Everyone in New York, it turns out, is implicated in this sort of smarminess. Even she isn't immune to it – crying at her own memorials, especially when she is drunk, starting to break up at the sound of her own name."

To convey all of this Hecht sets Hazel's "last days" in the context of the newspaper world, one he knew intimately starting with the job he won at the Chicago Daily News after writing an obscene poem for the publisher to read aloud at a party. Hecht was always happy to acknowledge the public's lingering distaste for his former profession: when Wally introduces himself to Downer, the doctor exclaims that he can always smell a newspaperman and opens the windows of his office to air out the room.

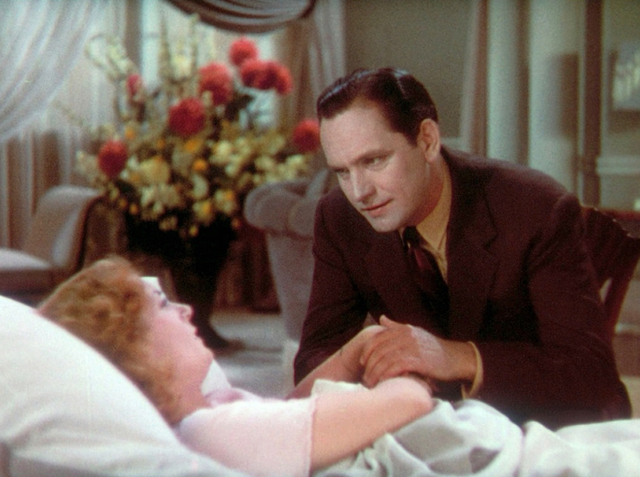

Wally is far more troubled by his exploitation of Hazel – especially as they begin falling in love – but he persists in the whole charade nonetheless, even as he complains about the unhealthy codependence between his profession and the public it "serves".

"We give them a chance to pretend that their phony hearts were dripping with the milk of human kindness," is how he bitterly sums it up near the end of the picture.

The tributes to Hazel become increasingly ridiculous. Hazel responds by following Dr. Downer's lead and getting wall-eyed drunk, passing out on the stage during "Mother Earth Salutes Hazel Flagg". (Looking lovely as she does so, of course; Lombard is one of those rare actors who can play a great drunk.) A group of school children arrive at her hotel suite to serenade the dying (though actually hungover) girl with a ditty sung to the tune of "The Battle Hymn of the Republic."

Wally seems to luxuriate in his maudlin emotions as he falls for the "dying" Hazel. Lombard responds with a weak smile as he denigrates himself for prospering "over your poor pain-wracked little body" and compares himself to his readers, who consider themselves ennobled by demonstrating their pity for Hazel with every newspaper they buy. "They try to confuse feeling generous with being it," as Harvey sums it up.

This makes Nothing Sacred the first attack on "virtue signaling" decades before the phrase would be coined. If it were remade today it would be a comedy about social media, complete with TikTok posts and hashtags like #poorhazel and #dyinggirl, and Hazel's pyrrhic fame would be as an influencer.

"This Ben Hecht screenplay," Harvey writes, "is less the Front Page view of the city, as a center of hopeless political and social corruption, than the Holden Caulfield one: the place is full of phonies. All of them weeping over Hazel – jaded sophisticates, working-class slobs at wrestling arenas, and self-important public figures in private delegations to her hotel suite."

"Nothing Sacred was also the first screwball comedy to lay apparent claim to larger satiric meanings, to make scathing observations about American life and society. It sets out to demonstrate what a more modest comedy like True Confession simply assumed: that the corruption and phoniness are nearly total."

The jig is finally up, though, when Wally's boss pays for a quartet of European specialists led by Dr. Emil Eggelhoffer (Sig Ruman) to examine Hazel with a view to a possible cure. They report that she's perfectly healthy, and an enraged Stone orders up muscle from the paper's circulation department to drag Hazel out of her hotel suite and keep Wally prisoner in his office.

In the meantime Hazel has planned a staged suicide with the connivance of Dr. Downer in a rowboat to pull her from the water and whisk her back to obscurity. (Her suicide note is discovered by Troy Brown's bootblack con man, now employed by the Star, who finds it while raiding the floral tributes in Hazel's suite for a bouquet to bring to his wife.)

Their farce is foiled by Wally, who nonetheless knocks her into the water before realizing he can't swim. They're rescued by the fire department (with John Qualen doing the same comic Swede we saw two weeks ago in John Ford's The Long Voyage Home, complete with "yumpin' yiminies") and get whisked back to her rooms at the Waldorf to the blare of sirens.

In love and trapped by her lie, Wally and Hazel respond with that beloved screwball trope: the knock-down, drag-out "battle of the sexes." They start swinging at each other, both of them connecting with knockout blows to the jaw. (Lombard was coached for the scene by 1930 light heavyweight champion Maxie Rosenbloom, who plays one of Stone's enforcers from the Star's circulation department.)

In the end there's no way out but for Hazel to stage her disappearance with the full connivance of Stone and the Morning Star, complete with farewell note on the front page. Wally and Hazel are last seen on a steamship headed for the South Seas with a sauced Dr. Downer locked below in a room in steerage. Spotted on deck by one of Hazel's new legion of acolytes, the incognito heroine tries to brazen it out by joking about her resemblance while calling Hazel a fraud, to the outrage of the true believer.

As in nearly every screwball film she made, it's Lombard's persona and charisma that helps put all the chaos and improbability over. "She is like someone in a state of irrepressible mania elation who's compelled to attend a wake," as Harvey writes:

"Nothing Sacred jokes obsessively about Hazel's 'gallantry' in facing death, but the most powerful effect Lombard conveys is the gallantry of someone facing life. The movie tells us that everyone is implicated in hypocrisy and self-deception, but Lombard tells us that some people are mysteriously, triumphantly untouched by this general atmosphere: they are simply too daring, too funny, too full of sense and life."

Wellman's film was not a hit, losing $350,000, though having to compete with another Lombard screwball at the same time probably didn't help, and it would fall into public domain in the U.S. when its copyright wasn't renewed in 1965.

Hecht's script would be turned into a Broadway musical, Hazel Flagg, in 1953, and a year later Norman Taurog would direct Living It Up, a gender-swapped remake with Jerry Lewis in the Hazel role, Janet Leigh as the reporter and Dean Martin as the small-town doctor. Sig Ruman would reprise his part as Dr. Egelhofer. This time around the story made money. Go figure.

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.