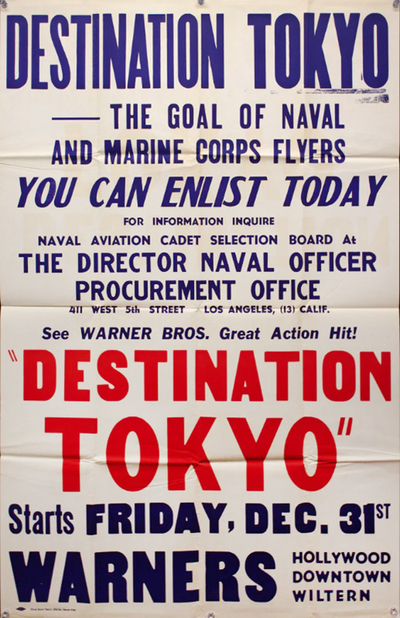

It goes without saying that every war film (and a few other besides) that Hollywood made during World War Two was a propaganda film. Nobody would mistake Destination Tokyo (1943) as anything but propaganda, made by Warners, arguably the most jingoistic of the Hollywood studios, and at the moment when the tide of battle finally seemed to be turning in the Allies' favour – after the Soviet triumph at Stalingrad and the defeat of Rommel in North Africa, the Dambuster raid and the withdrawal of German U-boats from the North Atlantic.

The film looks back at the first months of America's entry into the war – a year of almost constant bad news alleviated only by the Doolittle Raid and the US victory at Midway. In her book The World War II Combat Film, Janeane Basinger puts Destination Tokyo at the end of a cycle of films that began with MGM's Bataan and included Sahara, Guadalcanal Diary and Air Force: films that broke with the form that war films had taken over previous decades and helped define WW2 pictures for audiences living through the ongoing conflict.

"Bataan," Basinger writes, "is not the work of art that Citizen Kane is, but what Kane did for form and narrative, Bataan does for the history of the combat genre. It does not invent the genre. It puts the plot devices together, weds them to a real historical event, and makes an audience deal with them as a unified story presentation – deal with them, and remember them."

Destination Tokyo begins in Washington DC, in the War Department offices that would move into the under-construction Pentagon by the time 1943 began. We watch an order get drafted and conveyed to San Francisco, to the Mare Island shipyard where a submarine, the USS Copperfin, is being prepared for a combat patrol.

From conversations between the Cassidy (Cary Grant), the sub's captain, and his crew we learn that this is to be their sixth patrol, and that Cassidy assumes it'll be his last – if he survives. The Copperfin under his command has been too successful, and Cassidy's reward will be promotion to a desk job suitable to the new third stripe on his uniform sleeve and the "scrambled eggs" on his cap.

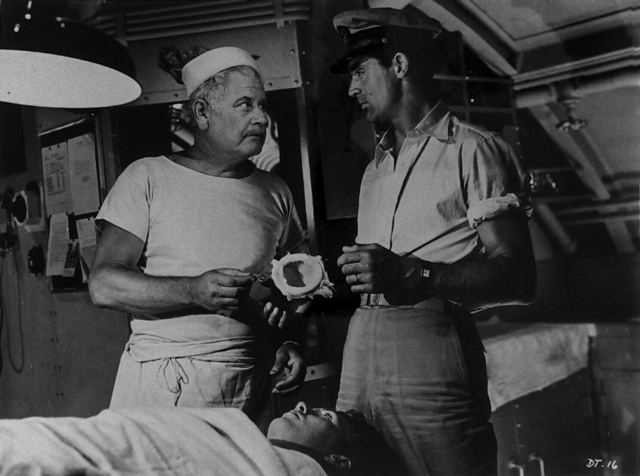

The boat is loaded with munitions and torpedoes, to an ominous, purposeful soundtrack, but also with humanizing cargo, like the carton of the captain's favourite chili sauce carried by "Cookie" (Alan Hale Sr.), the sub's mess chief and the movie's designated comic relief. It's just one of the dozen or so roles that the classic WW2 film requires according to Basinger, which includes the Hero, the Adversary, the Noble Sacrifice, the Peace Lover, the Old Man and the Youth, and the representatives of Minorities and Immigrants.

The standouts among Cassidy's crew are the skirt-chasing Wolf (John Garfield), "Pills" the pharmacist's mate (William Prince), the hot-headed Greek "Tin Can" (Dane Clark), the navy veteran Mike (Tom Tully) and the raw recruit Tommy (Robert Hutton). If you're aware of the character list Basinger lays out for films like Destination Tokyo, you're able to discern their function minutes after the credits have rolled.

After acquainting us with the Copperfin's crew and their high opinion of Cassidy, we watch them sail beneath the Golden Gate bridge and out to sea, churning out exposition and backstory as they go. Precisely 24 hours from casting off the captain opens his safe and reads his sealed orders, which send them up to the Aleutians to pick up Lt. Raymond (John Ridgely), a navy meteorologist.

Raymond is to be taken to Tokyo Bay and rowed ashore with a small team to scout the harbour and radio intelligence and weather conditions to where the navy and air force are launching an unprecedented bombing mission from an aircraft carrier – the Doolittle Raid. Their mission is crucial to the success of the raid, we're told, and will give audiences a glimpse of this historic first blow against the Japanese homeland that they'd have to wait another year to see in detail, with the release of Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo.

Director Delmer Daves began his Hollywood career at the bottom – as a prop boy and bit player before he got an opportunity to work on screenplays in the early years of sound. He wrote pictures like Dames (1934), The Petrified Forest (1936) and You Never Were Lovelier (1942), then got his break as a director with Destination Tokyo, co-writing the screenplay with Albert Maltz,

Six years after Topper made him the king of screwball comedy and The Awful Truth made him a star, Grant sidestepped his usual persona to take the role of Cassidy – his first foray into drama since Suspicion (1941). Warner Bros. swapped Grant from Columbia so that Humphrey Bogart could play a tank commander in Sahara, after Gary Cooper turned down the role of the Copperfin's captain.

The picture was made with the full cooperation of the US Navy, who saw it as a recruiting tool for the "silent service" that they'd unwisely neglected during peacetime. They even arranged for Dudley "Mushmouth" Morton of the USS Wahoo, the most celebrated sub skipper in the service, to act as technical advisor on the picture. A month after filming ended Morton and the Wahoo were sunk during a mission into the Sea of Japan. In 2005 the sub was found nearly intact at the bottom of the La Pérouse Strait.

Destination Tokyo was the film that set the template for the sub picture, but today the archetype is any of several versions of Das Boot, Wolfgang Petersen's seminal 1981 U-boat picture, whose dank, greasy, claustrophobic and dim portrait of life in a World War Two submarine was so vivid you could smell it; it would be nobody's recruitment picture.

By comparison life aboard the Copperfin looks pleasant – cramped, to be sure, but clean and well-lit, very much in the tradition of American sub pictures, which imagine the well-appointed US Navy ship benefitting from every technology and mod con that can be squeezed into a very large cigar tube.

And it's a welcoming place – an "enclosed world, separate from the one they left behind" as Basinger describes it. "These men have a kitchen, bedrooms, places to relax and talk. They have a cook who acts as a mother to them, and they have each other. Theirs is the world of combat, but it's a family world."

The fact that Destination Tokyo was made in the middle of the war it depicts creates a dynamic particular to the social utility of this kind of propaganda. We know these men have families – they're talked about, evoked in pictures and mementoes, and shown in flashback scenes throughout the picture that "indicate a prior life for the characters, just as they also indicate a prior film," writes Basinger.

"The statement made by the use of these flashbacks is that the prior life, the prior film, and the prior audience life must all be jettisoned for the war effort." Because what separates the war film made during the conflict from those made afterward – and often decades later – is that almost anyone paying to see the film on its release would either have a direct role in the war or share close ties with someone who does. They all, to put it crudely, had skin in the game.

And it's why the film's function as propaganda gives voice to an animosity toward the enemy – a palpable hatred, there's no other way to put it – that can make us uncomfortable today.

Picking up Lt. Raymond from a Catalina flying boat off the Alaskan coast, the Copperfin is discovered by a pair of Japanese scout floatplanes who strafe and dive bomb the sub. One plane puts a dud bomb into the Copperfin's deck, and while both are shot down, one pilot manages to bail out and swim toward the sub.

When Mike climbs into the water to pull the pilot on board and into captivity, the Japanese stabs him to death before Tommy empties dozens of rounds from a heavy machine gun into the pilot. The young recruit had developed a bond with the older sailor and is stricken with guilt for reacting too slowly, but Cassidy explains that the Japanese pilot had been raised to hate – given a dagger as a 5-year-old child and relentlessly taught how to use it.

This message is echoed by Raymond, who was raised in Japan and speaks the language. He tells the crew how the Japanese don't love their women the same way they do – that there's no word for that kind of love in their language – and that poor Japanese girls are sold to factories "or worse" at the age of twelve.

"The ideas of why we are fighting the war are discussed," Basinger writes, "and heavy propaganda is established as to the cruelty and treachery of the enemy, as well as its intelligence and its worthiness as an adversary."

While wartime propaganda films occasionally made room for the "good German" and had no problem imagining that Italians had been haplessly led into a war they couldn't win by an oafish leader, the harshness and bigotry of Hollywood's depiction of the Japanese is impossible to overlook, especially when compared to how quickly its view of Japan modulated to curiosity and even fascination as soon as the war was over.

It has to be remembered that Japanese propaganda was even more overwhelming and their portrayal of the American enemy just as brutish; it was the reason why fleeing and cornered civilians committed suicide with tragic eagerness – to the horror of soldiers and Marines when they invaded Saipan and Okinawa. Unique among wars, the victors of World War Two presume a virtue cast in sharp relief by the terrible deeds of their enemies, so it's still shocking to rediscover, over and over, how crude our propaganda could be even generations later.

And since this was a world war, the film evokes the other enemy in the theatre of war on the other side of the world. When the men confront Tin Can about why he wasn't on deck for Mike's burial at sea, the sailor – the most openly eager for action of the whole crew – is forced to tell them about his uncle in Greece, shot by the Nazi invader for the mildest show of resistance. His hatred for the enemy is so deep and personal that even a victim of its ally reminds him of his beloved uncle.

Hoping to atone for Mike's death, Tommy volunteers to climb inside the hole in the decking and try to defuse the bomb lodged there. With Cassidy's coaching he manages to extract the detonator, which the skipper shows off to the crew, pointing out its "Made in USA" stamp: "The appeaser's contribution to the war effort!" In 1943 there were obviously both new and old scores to be settled.

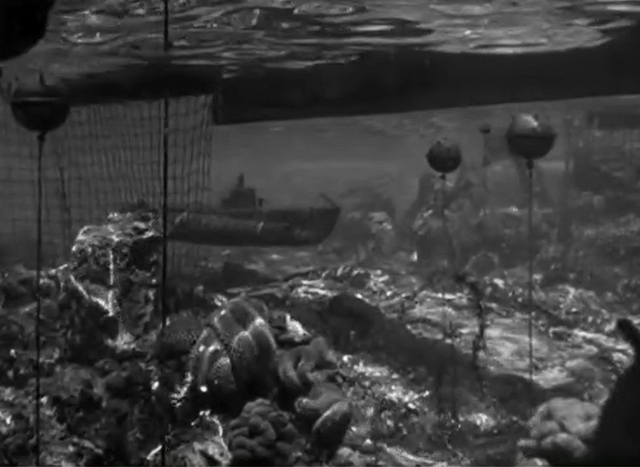

The rest of the film is taken up with the mission, which involves sneaking through Japanese mine fields and submarine nets by sailing just under the stern of their own warships entering the harbour. They put Raymond and his team ashore for their espionage and sail deeper into the bay to note the defenses, the barrage balloons and the Mitsubishi factory. It even gives them a periscope-level front seat on Doolittle's raid.

"These units of story appear over and over again in later submarine films," writes Basinger. "They represent the need to work against time (defusing the bomb, or emergency diving when someone is still up top); the constant threat of death; the need for patience during long periods of helplessness; and the primary importance of working well together."

But there's no reason to believe that there was any submarine or covert operation to collect weather data crucial to Doolittle's mission (even though the story of the brave sub crew is told again in Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo a year later). And in any case Doolittle's B-25s were forced to begin their mission early when their carrier task force was discovered by a Japanese ship.

What is true is the most outlandish dramatic intrusion into the Copperfin's mission – the emergency appendectomy Pills is forced to perform on Tommy when he falls suddenly ill while the sub is in enemy waters. A year earlier the USS Seadragon was forced to sit on the bottom of the South China Sea for five hours while its pharmacist's mate used scalpels and implements fashioned in the mess to remove a crewman's burst appendix.

The climax of the picture is the Copperfin's escape, through the minefields and sub nets in the shadow of another enemy ship, before it sinks a Japanese aircraft carrier with its torpedoes and endures endless depth charge attacks. Damaged and leaking, they fight a final duel with a destroyer and emerge triumphant, ending the picture back beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, longing for the comforts of home – cold farm cider, Dinah Shore records, green vegetables and girls.

Given the demoralizing difficulties of the submarine war in the year after Pearl Harbor, the Copperfin would have been the most successful sub in the fleet if it were real. The USS Sailfish was actually the first US sub to sink a Japanese aircraft carrier, the Chuyo, in the first week of December of 1943 – just days before Destination Tokyo had its premiere at a charity event in Pittsburgh.

And this was only possible because it had taken more than a year for the Navy to overcome a lingering self-inflicted wound – the dismal performance of the Mark 14 torpedo and its Type 6 detonator. The failure rate of American torpedoes through 1942 and 1943 was shocking – at one point barely one in ten exploded on their target, the rest either detonating early or not at all, sailing underneath their target and out to sea, going on wild random journeys after launch, curving around to head back to the sub that launched them or simply failing altogether just after leaving the torpedo tubes.

(Early after America joined them in the war, the British had politely declined buying any Mark 14 torpedoes from their ally, reasoning that they had enough problems as it was.)

Underfunded and risk-averse, the Navy had barely tested the Mark 14 during peacetime, and pleas from sub skippers to either fix them or remove them from service were actually ignored or stifled by Admirals who had a hand in their development. Famously the USS Tinosa had expended all but one of its torpedoes trying to sink the Tonan Maru over two days in the summer of 1943, at one point lining up the crippled Japanese tanker point blank, firing torpedo after torpedo to no effect.

The Tinosa's skipper arrived back in Honolulu and stormed into the office of Rear Admiral Charles Lockwood, who expected "a torrent of cusswords, damning me, the Bureau of Ordnance, the Newport Torpedo Station and the Base Torpedo Shop, and I couldn't have blamed him." But the skipper was so apoplectic that he was speechless. The humiliation finally forced the Navy to do the testing they'd resisted for years, and discovered the only way the torpedo and its detonators actually worked was with a lucky, glancing shot.

But this wasn't a story Hollywood or the US Navy was going to tell just two years after Pearl Harbor. Submarine movies wouldn't be able to talk about the Mark 14 dud torpedoes until Operation Pacific (1951) starring John Wayne. In that film the crew of the USS Seahawk are shown screening a print of Destination Tokyo for entertainment while on patrol.

"As they watch, one man falls asleep and one walks out," Basinger writes in her book. "When asked how he liked the picture, he replies 'Oh, all right, I guess. The things those Hollywood guys can do with a submarine!'"

It's as meta a moment as Hollywood could manage, at least until Singin' in the Rain came out a year later.

Tony Curtis said that he was inspired to join the navy after watching Cary Grant in Destination Tokyo. Years later he'd be cast as Grant's second in command in another sub picture, Blake Edwards' Operation Petticoat (1959), which Basinger describes as a "feminized" version of Destination Tokyo, right down to the boat going into combat painted pink.

Nearly twenty years after Pearl Harbor, enough time has elapsed to distance us from a time that, as Basinger says, "seen close and felt as real, would not be funny."

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.