On the fourth of July weekend in 1947, a group of bikers rode into a small California town and, depending on who you believe, either had a great party or went on an orgy of destruction. This single incident – now famous as the Hollister Invasion or the Hollister Riot – created both the abiding myth of the outlaw biker and the renegade bike gang, and inspired the movie that provided the template for every other biker movie to follow.

The occasion was the first major bike rally held by the American Motorcycle Association in California since before World War Two, and while attendance was expected to be high, nobody anticipated what would really happen. Hollister – about two hundred miles south of San Francisco and inland from Monterey and Carmel – had always been friendly to bikers, hosting regular races and hill climbs on the Bolado Racetrack.

It had, according to Tom Reynolds' Wild Ride: How Outlaw Motorcycle Myth Conquered America, "twenty-seven bars, twenty-one gas stations and only six policemen." It had its own bike club, the Tophatters (still in existence today) – one of dozens, probably hundreds of groups of mostly ex-servicemen who got together to ride, race, drink and raise a bit of hell just before the Hell's Angels formed a year after Hollister and took over the image of the outlaw biker forever.

"Nobody has ever fully explained what happened in the town on Independence Day weekend in 1947," writes Reynolds, "because the allure of the myth is far more tantalizing than whatever facts can be gleaned from eyewitnesses or news photographs. Descriptions run from just a wild party to a rural version of the Rape of Nanking."

Hollister would inspire a film, The Wild One (1953) – the film that Marlon Brando made between A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) and On the Waterfront (1954) and arguably did more than either film to create Brando's persona, both on and off the screen. Its basic plot – bike gang comes into conflict with squares, causes mayhem/destroys small town/inspires vigilante payback – is really just a western with wheels instead of hooves, which is why it would be so easy to copy for decades to follow, in films with titles like Dragstrip Riot, The Wild Angels, Devil's Angels, The Rebel Rousers, Angels from Hell, She-Devils on Wheels, Satan's Sadists, Angel Unchained and dozens more whose plots vary as much as their titles.

The Wild One begins with a warning: "This is a shocking story," the boldface card explains over a shot locked off just above the asphalt of a country road stretching to the vanishing point. "It could never take place in most American towns – but it did in this one."

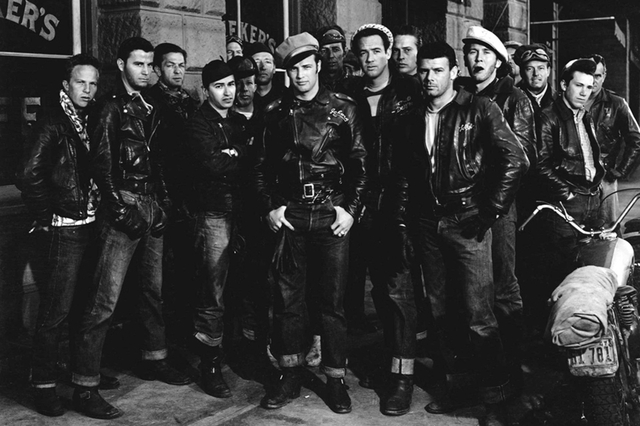

"It is a public challenge not to let it happen again." With Hollister duly evoked, the camera rests on the road until a group of motorcycles converge on us, one of the bikes fishtailing just before it runs the camera over. Cut to a process shot, Brando the centre of a trio of bikers in front of a rear projection of the rest of the gang. The biker on Brando's left wears goggles and has a cigar clenched in his teeth; the biker on his right is slouched sullenly behind his handlebars, a Civil War cap on his head. None of them look like they're riding anything but a stationary bike being moved by stagehands.

The first time I watched The Wild One as a teenager I constantly wondered when I'd seen it before; every plot point and conflict worn itself into the pop culture collective memory of the "biker picture" I shared with everyone else: the combination of curiosity, excitement and revulsion when the locals encounter Johnny Strabler (Brando) and the Black Rebel Motorcycle Club; the gang's goofy mix of childish provocation and cornball hipster slang; the belligerent square john local businessman who insists they have to take matters into their own hands and teach these hoodlums a lesson.

Even Johnny's signature line, among the most famous Brando ever uttered in his career ("Hey Johnny, what are you rebelling against?" "What do you got?") had been rendered as rote as pantomime by the time I finally saw it on screen and in context.

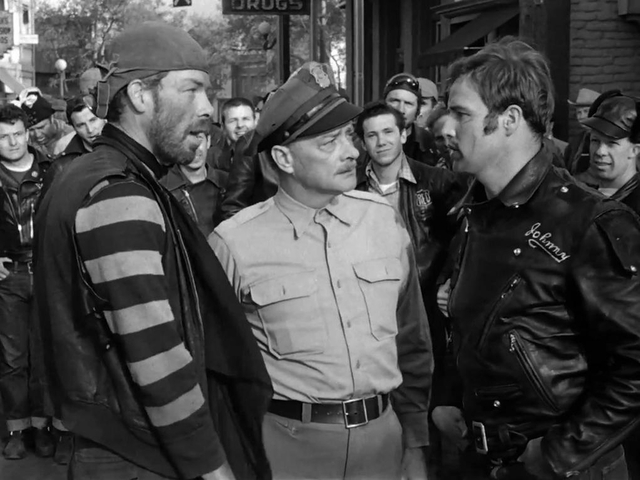

The Wild One – directed by László Benedek (Song of Russia, Death of a Salesman), produced by Stanley Kramer and based on "Cyclists' Raid", a short story by Frank Rooney published in Harper's magazine – strains for relevance. Even the costume Lee Marvin wears as Chino, leader of rival bike gang The Beetles, is based on "Wino Willie" Forkner, founder of the Boozefighters, the outlaw gang that was blamed for most of the trouble in Hollister.

(Forkner was a consultant on The Wild One but quit in protest at the portrayal of bikers. The Boozefighters are still around, with chapters all over the world.)

The pictures produced or directed by Stanley Kramer, king of the "message film", are impossible to ignore as artifacts of social history from the '40s to the '60s. But with the exception of High Noon (1952) they generally aren't very good. They also weren't big box office for Columbia while he had a deal at the studio, and they'd announced the dissolution of his Columbia partnership just as The Caine Mutiny (1954), his final picture with the studio, became a massive hit.

Kramer's pictures lack any lightness of touch, and even It's A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963) with its ensemble cast top-loaded with comedians groans and wheezes on its way to delivering laughs like heavy machinery stripping away a cliff face.

It's easy to confuse a film like The Wild One with the explosion of juvenile delinquent pictures that would arrive in its wake (Blackboard Jungle, Rebel Without A Cause, Girls Town, The Violent Years). But the bike gangs that invaded Hollister, like the Black Rebel Motorcycle Club and The Beetles, are comprised of grown men, most of them veterans.

"While the majority of the Greatest Generation returned to raise children, build Levittown, and elect Eisenhower," writes Tom Reynolds in Wild Ride, "guys like the Boozefighters tried to exorcise their personal demons through motorcycling. They spent much of their time getting drunk, howling at the moon, drag racing in the L.A. River aqueducts, and avoiding the police."

"As a pop culture phenomenon, The Wild One is rife with contradiction," he continues later in the book. "It is a classic film that is also a bad movie, the first youth-gone-wild tale in cinema history, featuring a cast of characters who are pushing thirty. In terms of portraying motorcycle culture at the time, the movie got almost everything wrong, but this didn't stop bikers who likely knew better from being influenced by it."

Rock and roll, the music of the juvenile delinquent, wouldn't really get its name until a year after the picture was released, around the time Elvis Presley first walked into Sun Studios in Memphis. The scat-like "rebop" the bikers use to baffle the ancient Jimmy (William Vedder) at the café and bar they take over was an invention of eccentric bebop legend Slim Gaillard, and the records they play on its jukebox are mostly Stan Kenton-esque big band jazz.

Re-watching the film today, I'd say that Mary Murphy's Kathie, the sad, trapped local girl who Johnny sticks around town trying to impress – setting in motion the ensuing sacking and rioting – is as good as Brando, possibly better considering her underwritten role; she mostly reacts for the first half of the picture, mostly runs away for the second.

(Murphy would have two good roles after The Wild One – opposite Humphrey Bogart in The Desperate Hours (1955) and in A Man Alone (1955), a western starring and directed by Ray Milland. Much of her career after that was in television, but she got another good part as Steve McQueen's unimpressed sister-in-law in Sam Peckinpah's Junior Bonner of1972.)

The decades after The Wild One would be big ones for outlaw bikers and bike gangs, and Reynolds was right that the picture did a lot to inspire the increasingly notorious image of "one percenters" as clubs like the Hell's Angels increasingly came to resemble organized crime. My own working-class neighbourhood in west end Toronto was home to at least two biker clubhouses when I was a boy, and I vividly recall choppers thundering along Lambton and Weston Roads, their riders wearing Satan's Choice colours (before they patched over to the Outlaws and, eventually, Hell's Angels.)

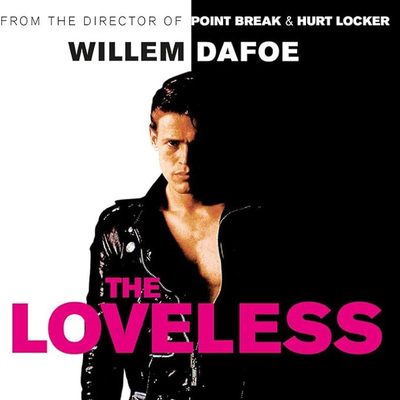

Nearly thirty years after The Wild One came out I found myself at a film festival screening of the debut film of a director destined to win an Oscar among countless other awards. The Loveless (1982) was not only Kathryn Bigelow's debut feature but the first starring role for Willem Defoe, playing a distilled variation on Brando's Johnny.

Bigelow would make her name with creative genre and action pictures like Near Dark (1987), Point Break (1991), her Oscar-winning The Hurt Locker (2008) and Zero Dark Thirty (2012). But she shared writing and directing credits on The Loveless with Monty Montgomery, who would go on to produce David Lynch's Wild at Heart (1990, with an indelible turn by Dafoe as Bobby Peru, the film's villain) and appear as The Cowboy in Mulholland Drive (2001).

The Loveless is essentially a knowing but affectionate post-punk cover version of The Wild One; I'd compare it to Howard Devoto and Magazine's version of Shirley Bassey's "Goldfinger" or The Slits doing Marvin Gaye's "I Heard it Through the Grapevine". (But thankfully not the Sid Vicious version of "My Way".)

After the opening warning of The Wild One, and before the bikes roared down on the viewers, we'd heard Brando's Johnny in a voiceover: "It begins here for me on this road. How the whole mess happened I don't know." Bigelow and Montgomery begin their film with Dafoe's Vance in voiceover after we see him get on his 1955 Harley Hydra Glide panhead, after spending the night sleeping rough in a field; as he drives down an empty country road we hear him in voiceover:

"Man, I was what you call ragged. Way beyond tore up. I wasn't going to be no man's friend today."

Brando's voiceover attempts to sound natural, even contrite. Dafoe's lines are defiant, and more than a bit arch; not long after that he tells us that "I knew I was going to hell in a breadbasket" as a tip-off that this film won't be delivering a message or attempting to make its late '50s setting naturalistic. This is the past, and things look and sound different here.

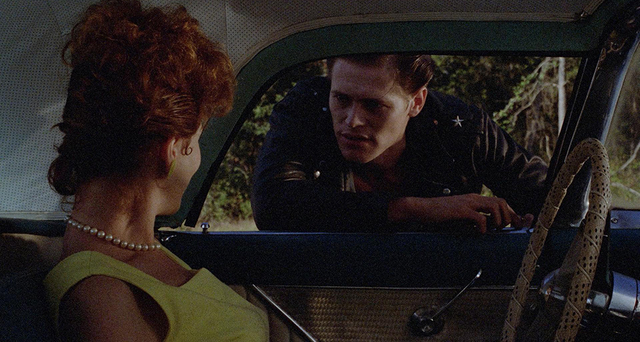

Vance passes a woman in a T-Bird with a flat on the side of the road. He turns his Harley around and offers to change her tire; she's afraid at first, then turned on, and assumes that he wants sex when he asks "Now what you got?"

But he wants money; she tells him that normally she's on the receiving end of this transaction while she goes through her purse, which he snatches out of her hand and empties before leaning into the car and planting a long, rough kiss on her. Vance walks away giggling, imitating her groans of pleasure.

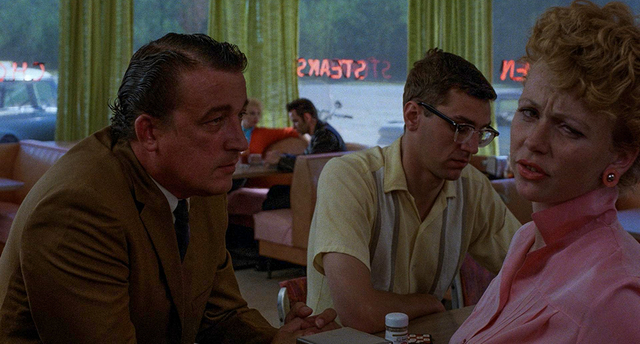

The biker parks at a truck stop, buys cigarettes and takes a seat in the corner booth overlooking the parking lot. The hard-mouthed owner, Evie (Margaret Jo Lee), with her coral pink lipstick, doesn't want to serve him, but her pretty, freckled waitress Augusta (Elizabeth Gans, looking like a downcast Doris Day who never caught a break) is intrigued. Vance asks her why anyone would live in a place like this, and she tells him that she was born here, but couldn't find the energy to leave when her husband died after falling off a scaffold.

The camera lingers on the details of the diner with the morning sun slanting through the big windows, taking in the Formica counters, the shadows of the lettering on the windows, the flies buzzing on a leftover plate of eggs, Vance silently studying the parking lot and the road. The world used to be full of places like this, and my generation – or at least the ones who came of age in the shadow of punk rock, and its abiding fascination with Americana and the pre-Beatles world – took in every diner, dive bar, cocktail lounge and motel like a hiker in the English countryside coming across an ancient church or ruin.

Sitting in the Kingsway Theatre on a weekday afternoon at the start of my last year of high school, I knew instantly that this film was made for me.

The rest of Vance's gang finally arrives: La Ville and his lethal sideburns (Lawrence Matarese), Davis (musician Robert Gordon) and his biker bombshell girlfriend Sportster Debbie (Tina L'Hotsky – her actual birth name, with only the apostrophe added). Davis is the most tightly wound member of the group; over the course of the film we're meant to understand that he's got an unsolved murder in his recent past, and that he'd add a few more to it for the right price. Vance and his gang might be ex-cons and thugs, but Davis is an actual psychopath.

There are two missing members of the gang holding them up on their way to watch the races at Daytona Beach. Hurley (Philip Kimbrough) has busted the chain on his Harley and needs a garage to make repairs. When he finally turns up with the bike on a flatbed he's accompanied by the photogenic Ricky (Danny Rosen), who gives Sportster Debbie competition for looks.

Vance heads off and bargains with a local gas station owner for space in his garage; their morning is cut with scenes of Tarver (J. Don Ferguson), the big man of the town, as he tends to his main business – siphoning fuel from a pipeline and storing it in the gas station's tanks.

While the gang tends to Hurley's bike they get a visit from Telena (Marin Kanter) in her Corvette. She's Tarver's daughter and the town's designated jailbait; the car was a gift to shut her up after he hit her on the night her mother killed herself. She likes the look of Vance, who asks her what a "bum's got to do to drive a car like this."

"Turn the key," she says.

While they drive around she learns that Vance is from New York, and that he met the rest of his gang in prison, where he was serving time for stealing cars and violating the Mann Act. After buying beer and Thunderbird from a black-owned package store (Vance responds to the silent hostility of the owner by saying "I ain't as white as I look") they end up in a motel.

Watching some sort of sordid crime news footage on the TV post coitus, Vance hears gunshots. Tarver has shot out the tires on Telena's Corvette; while he drags her out of the room she wails that Vance didn't do anything to her that he didn't already. With as few words as possible, and as many long silences as the audience can bear (more back in 1981 than today, I'd bet) we have the whole Wild One template established, woven with a bit of incestuous Southern Gothic.

The Loveless is a highly stylized biker movie, a kabuki variation on the genre. Every character is an archetype, and the film frequently stops to take in its surroundings, like a time traveler amazed that nobody has noticed them yet. The gang works on Hurley's bike; the camera lingers on chromed details of the vintage Harleys, on their leathers and patches, on a pinup calendar on the wall.

To kill time Ricky, Davis and La Ville play a game of mumblety-peg, throwing their switchblades at each other's feet. As the town drowns its sorrows at the local lounge near the end of the film Tarver – his face dripping with sweat – declares that Vance and his gang are "communists". At this point there's nothing else you can stuff into The Loveless without cracking its perfect veneer.

Bigelow and Montgomery have telescoped three decades of biker movies and culture into their 82-minute film, adding in a bit of sordid Faulkneresque rural melodrama and more than a little of Kenneth Anger's homoerotic biker fetishism from his 1963 short film Scorpio Rising. There's no more depth to The Loveless than there was to The Wild One, but Bigelow and Montgomery aren't troubled with messages or relevance: their film is all beautiful surface, no character more important than any detail of the lost world they discovered along the roadside in Georgia.

"Somehow, Bigelow and Montgomery managed to keep these B-movie Bikesploitation plot points firmly steered towards the Art House," writes Paul D'Orleans in an appreciation of the film on the Vintagent website, "while the whole wicked machine flew right over the heads of critics and unsuspecting viewers alike. It still does. The Loveless is triple-clever, deserving multiple viewings to savor the spare dialogue, gorgeous visuals, amazingly hot Willem Dafoe, and superb soundtrack."

As the film comes to its conclusion we're waiting to see if the town is happening to the bikers or the bikers are happening to the town. The directors deliver just the right amount of sex and violence; by the time the smoke clears on the bodies they've made precisely the film a young man thought he was going to see when he paid for a ticket to The Wild Angels.

But the film hits its apex just before the cathartic explosion of gunshots and blood at the end, when the gang sit drunkenly around a table at the lounge, bragging about where they're going and what they're going to do. Dafoe's Vance – with a straight face that hints at the talent he'd demonstrate repeatedly over the decades to follow – silences them all by bellowing out four words that impeccably sum up The Loveless:

"We're going nowhere. Fast."

Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.