As a postscript to our Henry Mancini centennial observances on Wednesday's Q&A, here's a few more favourites of mine, focusing on a rather elegaic Oscar winner:

As a postscript to our Henry Mancini centennial observances on Wednesday's Q&A, here's a few more favourites of mine, focusing on a rather elegaic Oscar winner:

The Days Of Wine And Roses

Laugh and run away

Like a child at play...

The first great songwriting partnership of Henry Mancini's career was with Johnny Mercer - and it produced three big songs in the early Sixties and a lot of lesser ones that have percolated up in the years since. Yet, for a lyricist who'd written with Jerome Kern, Hoagy Carmichael and Harold Arlen, a collaboration with Mancini didn't seem such an obviously great idea at the time. It began, like so many things in Mercer's life, with a stray tune he chanced to catch one day. "Johnny was in the habit of writing lyrics for melodies he just happened to hear and like," Mancini told Gene Lees. "He'd hear some music on his car radio and call the station to ask what it was; that was another of his habits. The tune was 'Joanna', from the second Peter Gunn album. He wrote a lyric on it":

Joanna's like a day

With summer on the way

All beautiful and gay

And bright...

Mike Clifford, accompanied by Johnny Williams and his orchestra, made a record of it, and the song died and was promptly forgotten. But it remains the first composition to bear the credit "Music by Henry Mancini, words by Johnny Mercer". Peter Gunn, with its eponymous and extremely cool private eye, was a famous TV show in its day, and its Mancini theme tune is still known by millions of people who've never seen the show: It was revived in the film The Blues Brothers, and it's been covered by everyone from Emerson, Lake & Palmer to The Art of Noise. The creator of Peter Gunn was the producer/director Blake Edwards, and a couple of years later, working on a film called Breakfast at Tiffany's and in need of a composer, he called in his old friend. That's what Mancini was pre-1961: a "score" guy, the man who did the background music in a movie. He'd come up through the big bands, been an arranger for the Glenn Miller orchestra, and moved into scoring with such acclaimed dramas as Creature from the Black Lagoon and Abbott and Costello go to Mars.

But he wasn't a songwriter. So, for the point in the script of Breakfast at Tiffany's when Holly Golightly goes out on the fire escape and strums a number on her guitar, the producers decided to bring in a bigtime songwriter. As the picture was set in New York, they figured they'd hire a couple of Broadway guys to come up with something. Mancini begged and begged Edwards to be given a shot at the song. He knew he could write a tune - not just incidental music, mood music, instrumental themes, but an actual song-type tune. The studio decided to give him a chance. At that point, they were also planning on getting a singer in to dub Audrey Hepburn. But Mancini figured she could sing something if you wrote it with her in mind. So he wrote a simple, diatonic tune in C and kept it within her range. Blake Edwards loved it and asked who he wanted for the lyric.

Mancini said Johnny Mercer. It was 1961. "Hank, who's going to record a waltz?" sighed Johnny. "It hasn't any future commercially." Nonetheless, he took the melody away and called up a while later to tell his composer that he had three possible lyrics. Mancini was conducting the orchestra for a benefit dinner that evening, and asked Mercer to meet him in the ballroom of the Beverly Wilshire. He sat down at the piano, and started to play the tune. Mercer sang:

I'm Holly

Like I want to be

Like holly on a tree

Back home

Just plain Holly

With no dolly

No mama, no papa

Wherever I roam...

"I don't know about that one," said Mercer. Then he sang a second lyric, and finally a third:

Blue River

Wider than a mile

I'm crossing you in style

Some day...

And wrapping up:

We're after the same rainbow's end

Waitin' round the bend

My huckleberry friend

Blue River and me.

He didn't know about that one, either. There's no copyright in titles but Mercer had riffled through the Ascap archives and discovered some friends of his, like Joseph Meyer (writer of "California, Here I Come"), had already written songs called "Blue River":

Mercer said he had an alternate title: "Moon River". And Mancini (who had grown up in Ohio) replied that there used to be a radio show in Cincinnati by that name. Immediately, Johnny wanted to know whether the show had had a title song. "No," said Mancini, "it was just a late-night show where a guy would talk in a deep voice about various things". Indeed:

Long ago, as I recounted on our Mercer centenary podcast, Henry Mancini told me about sitting in that darkened ballroom at the Beverly Wilshire and getting chills up his spine as he heard for the very first time the line "My huckleberry friend". It's the essence of lyric-writing: a minimal number of words that seem to conjure a whole world. "Echoes of America," Mancini called it: Tom and Huck on the Mississippi, and a whole lot more. Many people congratulated Mercer on the line, but usually by way of praising its allusive qualities. As far as I know, the only person to ask him directly what a "Moon River" has to do with a "huckleberry friend" was the musical historian Miles Kreuger.

"You're the only one who has asked me," said a sheepish Mercer. "Everybody loves that image, but it's really a terrible mistake." Back when the song was "Blue River", the river itself was the huckleberry friend - huckleberry blue. In his haste to change the title from "Blue River" to "Moon River", he forgot to amend the image - to "my goldenroddy friend" or "my xanthodonty friend" or whatever. And for a while, until people started telling him what a brilliant allusive image it was, every time he heard "Moon River" on the radio, he cringed.

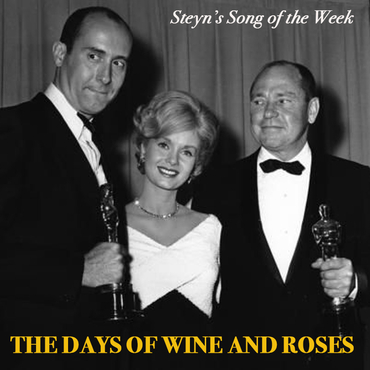

It made some other people cringe, too, for entirely different reasons. As Mercer gleefully reveals on our audio show, after a disastrous preview in San Francisco, Marty Rackin, Paramount's head honcho, said, "I don't know what you guys are gonna do, but I'll tell you one thing: that damn song can go" - or, as Mancini told it to me, "that f***in' song can go." It didn't, and it won the Oscar:

And, after that, Henry Mancini was a bona fide songwriter, and Mercer & Mancini were a team. For another Audrey Hepburn picture, this time with Cary Grant, they wrote "Charade", which I tend to prefer in finger-snappy Bobby Darin/Harry Connick Jr fashion:

For another Blake Edwards movie, The Pink Panther, they wrote "Meglio Stasera (It Had Better To Be Tonight)" - for the après-ski scene with Fran Jeffries wiggling round the room in sweater and pedal pushers. It's the best moment in the picture, and one the leaden Steve Martin remake sorely lacks:

That Italian lyric is by Franco Migliacci - the fellow who came up with "Volare". A couple of decades back, I suggested to a friend of mine that "Meglio Stasera" was (as I like to think of them) a truffle - a potential hit lying out there just waiting to be snuffled out the ground. Ten minutes later, I discovered that the very savvy David Foster and Michael Bublé were about to release it. I think their version comes close to burying the song, but it's a good example of how even minor Mancini has legs. Some of their later ballads - "Whistling Away the Dark" - have picked up steam over the years, too.

But, if I had to pick a single song to represent the best of the Mercer/Mancini collaboration, it would be their second Oscar winner, just a year after "Moon River", and for another Blake Edwards picture. Days Of Wine and Roses was a bleak little tale starring Jack Lemmon and Lee Remick as a young married couple in a ménage à trois: "You and me and booze - a threesome," as Lemmon's character tells Remick's. He becomes an alcoholic. Then she becomes an alcoholic. Then he claws his way back up from the depths. And she can't quite navigate that journey.

You wonder what Mercer made of the theme. I touched on his own drinking when we did "One for My Baby", and, as for days of wine and roses, as I mentioned here, for a famously mean drunk a lot of Mercer's days devolved into nights of wine ...and roses on the morning after, with hasty calls to florists to dispatch a compensatory bouquet to whichever close friend, casual acquaintance or hat-check girl he'd bawled out the night before. The half-decade before "Moon River", its Oscar and its Andy Williams single had been the biggest drought in Mercer's career. "I haven't had a hit song in years," he told his son-in-law, Bob Corwin, on the night Mancini happened to call up to tell him how well "Moon" was doing. It was a dry patch professionally but not alcoholically, and it fell to Corwin to accompany him from one bar to the next night after night and "get him out of there before he got killed because he was so belligerent". For Days of Wine and Roses, he certainly knew whereof he wrote.

The film was adapted by J P Miller from his Playhouse 90 TV drama of the same name, and Blake Edwards was insistent that the song also use the title. Mercer didn't like it. "It sounds like a French operetta, or the War of the Roses, or Sigmund Romberg, or Hammerstein and Kern," he said, "and you go in and you see two kids getting stoned out of their heads, and it's pretty depressing." Even worse, the title came from a Victorian poem, Vittae Summa Brevis:

They are not long, the days of wine and roses:

Out of a misty dream

Our path emerges for a while, then closes

Within a dream.

Those words were written by the English poet Ernest Dowson. So Mercer had to come up with a lyric that could hold its own with a pre-existing poem. And, just to add a cautionary note, Vittae Summa Brevis turned out to be self-fulfilling: Dowson - like Mercer, an alcoholic - died at the age of thirty-two in 1900.

A good professional movie composer, Henry Mancini listened to what Blake Edwards wanted. "The title determined the melody - six words, seven syllables," he said. "I went to the piano and started on middle C and went up to A, 'The days...'" He reprised the title phrase halfway through. When he played the tune for his lyricist, Mercer taped it on one of the first cassette recorders and took it home.

He poured himself a drink, leaned against the wall, and stared thoughtfully at the bar. An image came to him - of fleeting time, of days that "run away like a child at play". And at that point the lyric too just ran away:

The Days Of Wine And Roses

Laugh and run away

Like a child at play

Through the meadowland

Towards a closing door

A door marked 'Nevermore'

That wasn't there before.

Usually (as with, say, "Blues In The Night") Mercer wrote sheet after sheet of lyrics - words, lines, couplets, quatrains, choruses - and then he'd go back through them all and pick out the best. Not this time. What you hear is all there is. "I wrote it in five minutes," he said. "I couldn't get it down fast enough. It was like taking dictation. It just poured out of me." Mercer's entire text is just two sentences. That's the first one above. Here's the second:

The lonely night discloses

Just a passing breeze

Filled with memories

Of the golden face that introduced me to

The Days Of Wine And Roses

And you.

That was the one bit of rewriting he did: he changed "golden face" to "golden smile", which in keeping with the rest of the words is softer and less obtrusive. He didn't write about the demon booze. Instead, he fleshed out Ernest Dowson - the "misty dream" and the path that "emerges for a while, then closes" - or, more singably, laughs and runs away like a child at play through the meadowland towards a closing door, a door marked "Nevermore"... Mercer had warmed up to the late Mr Dowson by the time of the Academy Awards:

When I was very young, I interviewed Andy Williams, who, as he did with "Moon River" and "Charade", had a big record with "Days Of Wine And Roses":

"I love that song," I said, "The closing door marked 'Nevermore' in the meadow. But what does it mean?"

"I wish you hadn't asked that," he said, "because I don't really know."

As we've noted, Mercer got autumnal early. Indeed, he wrote a song called "Early Autumn", and he lived it. Maybe it was the booze, maybe it was the marriage, maybe it was just a tendency he shared with many other writers to overthink the whole intimations-of-mortality shtick. But from before his fortieth birthday and through songs like "Laura", "Autumn Leaves" and "When the World Was Young" there's a sense in his work of a man trying to pin down memories, of life and love in all their elusiveness. And, as soon as you do, they swim away again just out of focus - or laugh and run away. That's what Mercer is acknowledging here, and that's why the two-sentence text, unwinding with the contours of the melody, captures it so perfectly. Staccato phrases, lots of consonants, would have killed the song. That one rhyme for the title - "discloses" - could so easily have overbalanced the lyric, but instead it's perfectly poised to serve the number's point: the notion of the past slipping away, forever out of reach, except for grudging, fleeting sensations, "a passing breeze filled with memories".

It wasn't only Andy Williams who loved the song. Jack Lemmon told me about the first time Mercer and Mancini played it. It was after a long day's shoot of a grueling scene, and Blake Edwards insisted Lemmon accompany him to a big empty soundstage with a small upright piano in the middle. "I didn't want to go, but it turned out to be one of the greatest moments of my professional life," he said. "I'll never forget it. Hank began noodling just softly, softly, and Johnny pulls out an envelope and looks at the back just to remind himself, and Hank gives him the key note, and off he goes":

The Days Of Wine And Roses

Laugh and run away

Like a child at play...

Sitting at the piano, Mancini had his back to Lemmon and Edwards. At the end of the song, there was silence. Mancini stared down at the keyboard. Still silence. Nothing. Eventually, he turned around to see what was going on, and there were his director and his star with tears streaming down their faces.

They are not long, the days of wine and roses:

The lonely night discloses

Just a passing breeze

Filled with memories

Of the golden smile that introduced me to

The Days Of Wine And Roses

And you.

~If you enjoy Steyn's Song of the Week, the audio version airs thrice weekly on Serenade Radio in the UK, one or other of which broadcasts is certain to be convenient for whichever part of the world you're in:

5.30pm Sunday London (12.30pm New York)

5.30am Monday London (4.30pm Sydney)

9pm Thursday London (1pm Vancouver)

Whichever you prefer, you can listen from anywhere on the planet right here.

Membership of The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, but one thing it does give you is access to our comments section. So, if you're not partial to this week's choice and you're minded to laugh and run away to a door marked "Nevermore", then feel free to lob a comment below.

And don't forget, with Steyn Club membership, you can also get Mark's book A Song For The Season (which includes some of his most popular Song of the Week essays) and over forty other Steyn Store products at a special Member Price. You can find out more about The Mark Steyn Club here.